2021 Public Interest Careers

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

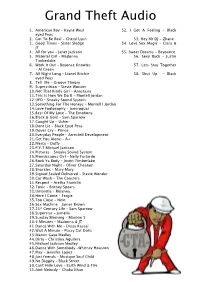

GTA Song List.Pages

Grand Theft Audio 1. American Boy – Kayne West 52. I Got A Feeling – Black eyed Peas 2. Got To Be Real – Cheryl Lynn 53. Hey Mr DJ - Zhane 3. Good Times – Sister Sledge 54. Love Sex Magic – Ciara & JT 4. All for you – Janet Jackson 55. Sweet Dreams - Beyounce 5. Material Girl – Madonna 56. Sexy Back – Justin Timberlake 6. Work It Out – Beyonce Knowles 57. Lets Stay Together – Al Green 7. All Night Long – Lionel Ritchie 58. Shut Up - Black eyed Peas 8. Tell Me – Groove Theory 9. Superstition – Stevie Wonder 10.Not That Kinda Girl – Anastasia 11.This Is How We Do It – Montell Jordan 12.UFO – Sneaky Sound System 13.Something For The Honeys – Montell l Jordan 14.Love Foolosophy – Jamiroquai 15.Best Of My Love – The Emotions 16.Black & Gold – Sam Sparrow 17.Caught Up – Usher 18.Dont Lie – Black Eyed Peas 19.Doves Cry – Prince 20.Everyday People – Arrested Development 21.Get You Alone – A+ 22.Mercy – Dufy 23.P.Y.T Michael Jackson 24.Pictures – Sneaky Sound System 25.Promiscuous Girl – Nelly Furtardo 26.Rock Ya Body – Justin Timberlake 27.Saturday Night – Oliver Cheatam 28.Shackles – Mary Mary 29.Signed Sealed Delivered – Stevie Wonder 30.Car Wash – The Coasters 31.Respect – Aretha Franklin 32.Toxic – Britney Spears 33.Umbrella – Rhianna 34.Here I Come – Fergie 35.Too Close – Next 36.Sex Machine – James Brown 37.21st Century Life – Sam Sparrow 38.Superstar - Jamelia 39.Sunday Morning – Maroon 5 40.4 Minutes – Madonna & JT 41.Dance With Me – Dizzy Rascal 42.Wait A Minute – Pussy Cat Dolls 43.Marvin Gaye Medley 44.Dirty – Christina Aguilera 45.Michael Jackson Medley 46.Dance With Somebody –Whitney Houston 47.Play – Jennifer Lopez 48.Just friends – Musique Soul Child 49.No Diggity – Black Street 50.Cant Hide Love – Earth Wind & Fire 51.Aint Nobody – Chaka Khan. -

Boston Legal Juiced Season 5, Episode 11 Broadcast: December 1, 2008 Written By: Corinne Brinkerhoff & David E

Boston Legal Juiced Season 5, Episode 11 Broadcast: December 1, 2008 Written By: Corinne Brinkerhoff & David E. Kelley Directed By: Michael R. Lohmann © 2008 David E. Kelley Productions. All Rights Reserved. Transcribed Imamess for Boston-Legal.org; Thanks to olucy for proofreading and Dana for pictures. At Crane, Poole and Schmidt, the elevator door rings, Margie Coggins steps off and seems to be looking for someone. Margie Coggins: Uh. She tries to get help from someone passing by. She is ignored and doesn't seem to know what to do next. Catherine Piper: She walks up. Hello, dear. May I help you? Margie Coggins: Yeah. I'm looking for a lawyer. Catherine Piper: Yes, I suspected as much. You're in a law firm. Uh, what have you done, dear? Margie Coggins: Well, I got into Harvard and then… Catherine Piper: A pretty little thing like you! Please! Who'd we do, sweetheart? Margie Coggins: Then they rescinded my admission. And now I would like to sue them. Catherine Piper: Of course you would. Uh…She grabs the hand of a person walking by and pulls her in. It's Katie Lloyd. Katie? Be a dear and help this young lady. Uh, Katie will help you, dear. Katie Lloyd: She looks at Catherine in puzzlement. To Margie. Why don't we go to the conference room? Still puzzled, Katie looks back at Catherine as she and Margie leave. Carl Sack: Hello. Catherine Piper: She turns. Ugh. And bumps into Carl. Carl Sack: Who are you? Catherine Piper: I'm Catherine, honey. -

1. Summer Rain by Carl Thomas 2. Kiss Kiss by Chris Brown Feat T Pain 3

1. Summer Rain By Carl Thomas 2. Kiss Kiss By Chris Brown feat T Pain 3. You Know What's Up By Donell Jones 4. I Believe By Fantasia By Rhythm and Blues 5. Pyramids (Explicit) By Frank Ocean 6. Under The Sea By The Little Mermaid 7. Do What It Do By Jamie Foxx 8. Slow Jamz By Twista feat. Kanye West And Jamie Foxx 9. Calling All Hearts By DJ Cassidy Feat. Robin Thicke & Jessie J 10. I'd Really Love To See You Tonight By England Dan & John Ford Coley 11. I Wanna Be Loved By Eric Benet 12. Where Does The Love Go By Eric Benet with Yvonne Catterfeld 13. Freek'n You By Jodeci By Rhythm and Blues 14. If You Think You're Lonely Now By K-Ci Hailey Of Jodeci 15. All The Things (Your Man Don't Do) By Joe 16. All Or Nothing By JOE By Rhythm and Blues 17. Do It Like A Dude By Jessie J 18. Make You Sweat By Keith Sweat 19. Forever, For Always, For Love By Luther Vandros 20. The Glow Of Love By Luther Vandross 21. Nobody But You By Mary J. Blige 22. I'm Going Down By Mary J Blige 23. I Like By Montell Jordan Feat. Slick Rick 24. If You Don't Know Me By Now By Patti LaBelle 25. There's A Winner In You By Patti LaBelle 26. When A Woman's Fed Up By R. Kelly 27. I Like By Shanice 28. Hot Sugar - Tamar Braxton - Rhythm and Blues3005 (clean) by Childish Gambino 29. -

Arts Education 4

2011 Saskatchewan Additional Learning Resources Arts Education 4 Arts Education: Additional Learning Resources 4 Prepared by: Student Achievement and Supports Branch Ministry of Education 2011 Arts Education 4 Arts education: additional learning resources 4 ISBN 978-1-926631-65-3 1. Art – Study and teaching (Elementary) – Bibliography. 2. Art – Bibliography. I. Saskatchewan. Ministry of Education. Student Achievement and Supports Branch. 016.37272 372.72016 All rights for images of books or other publications are reserved by the original copyright owners. Arts Education 4 Table of Contents Foreword ....................................................................................................v Dance - Print, Audio-visual, and Other Resources ..............................................................1 Drama - Print, Audio-visual, and Other Resources ............................................................27 Music - Print, Audio-visual, and Other Resources .............................................................33 Visual Art - Print, Audio-visual, and Other Resources ..........................................................66 Digital Resources ..........................................................................................107 Arts Education 4 iii Foreword ganized by strand, this list of learning resources identifies high-quality resources that have been recommended by the Ministry of Education to complement the curriculum, Arts Education 4. This list will Obe updated as new resources are recommended and older -

NOW WAP's WHAT I CALL MUSIC! Submitted By: Immediate Future Friday, 20 January 2006

NOW WAP'S WHAT I CALL MUSIC! Submitted by: Immediate Future Friday, 20 January 2006 EMI Music UK puts pop stars in your pocket with launch of mobile music store wap.the-raft.com bringing together music downloads, ringtones & videos from EMI Records, Virgin Records, Parlophone, Angel and Catalogue - http://wapinfo.the-raft.com Calling all music fans… Fancy going home with a Brit tonight? EMI Music UK extends ‘The Raft’ online music store from web to mobile with the launch of its mobile music site (http://wapinfo.the-raft.com). By texting ‘GO RAFT’ to 85080 (free text from all networks), music lovers will be able to access official artist news, breaking tour dates, music downloads and video, competitions and artist approved ringtones and realtones. And if you’ve got a bit of a creative urge yourself, you’ll be able to customise your own tracks by adding beats or special features to turn them into personalised ringtones (http://wapinfo.the-raft.com). Be the envy of all your friends with your totally exclusive ringtones! You’ll be kept up to date with the latest news and featured artist areas which include Artist A-Zs and weekly competitions in anyone of the following categories; pop, urban, dance, jazz and rock. Wap.the-raft.com (http://wapinfo.the-raft.com) will also host the UK top 10 ringtones plus specialist charts like alternative and Bollywood. Competitions include money-can’t-buy exclusive artist merchandise plus album collections—such as the Brits collection; a bumper hamper of Brits-nominated albums Wap.the-raft.com provides something for every music fan—in an easy-to-find mobile music format. -

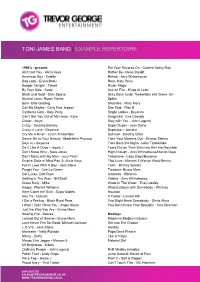

Toni James Band | Example Repertoire

TONI JAMES BAND | EXAMPLE REPERTOIRE 1990’s - present Put Your Records On - Corrine Bailey Ray Ain’t Got You - Alicia Keys Rather Be- Clean Bandit American Boy - Estelle Rehab - Amy Whinehouse Bag Lady - Eryka Badu Roar- Katy Perry Boogie Tonight - Tweet Rude- Magic By Your Side - Sade Sex on Fire - Kings of Leon Black and Gold - Sam Sparro Sexy Back Justin Timberlake into Grove Jet - Blurred Lines- Robin Thicke Spiller Burn- Ellie Golding Shackles - Mary Mary Call Me Maybe - Carly Rae Jepson She Said - Plan B California Girls - Katy Perry Single Ladies - Beyonce Can’t Get You Out of My Head - Kylie Song Bird - Eva Cassidy Closer - Neyo Stay with You - John Legend Crazy - Gnarles Barkley Super Duper - Joss Stone Crazy in Love - Beyonce Superstar - Jamelia Cry Me A River - Justin Timberlake Survivor - Destiny Child Dance Me to Your Beauty - Madeleine Peyroux Take Your Mamma Out - Scissor Sisters Deja vu - Beyonce Take Back the Night- Justin Timberlake Do It Like A Dude - Jessie J Tears Dry on Their Own into Ain’t No Mountain Don’t Know Why - Nora Jones High Enough - Amy Whinehouse/Marvin Gaye Don’t Mess with My Man - Lucy Pearl Telephone - Lady Gaga/Beyonce Empire State of Mind Part 2- Alicia Keys This Love - Maroon 5 (Kanye West Remix) Fell in Love With A Boy - Joss Stone Toxic - Britney Spears Forget You - Cee Lo Green Treasure- Bruno Mars Get Lucky- Daft Punk Umbrella - Rihanna Getting in The Way - Gill Scott Valerie - Amy Whinehouse Grace Kelly - Mika Wade in The Water - Eva Cassidy Happy- Pharrell Williams Wanna Dance with Somebody -

Power of Attorney

Louisiana State University Law Center LSU Law Digital Commons Journal Articles Faculty Scholarship 2008 Power of Attorney Christine Corcos Louisiana State University Law Center, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.law.lsu.edu/faculty_scholarship Part of the Law Commons Repository Citation Corcos, Christine, "Power of Attorney" (2008). Journal Articles. 220. https://digitalcommons.law.lsu.edu/faculty_scholarship/220 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Faculty Scholarship at LSU Law Digital Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in Journal Articles by an authorized administrator of LSU Law Digital Commons. For more information, please contact [email protected]. POWER OF ATTORNEY Christine A. Corcos * I. Opening Statements No doubt exists that the drama/farce 1 Ally McBeal , which ran on the Fox Television Network from 1997 to 2002 2, was a phenomenal success, at least during its middle years (1998-1999). 3 It sparked numerous fan websites in several countries 4 including one devoted to “fan fiction @5” (a genre in which devotees of a television series or film try their hands at writing scripts), various product spinoffs, 6 a series spinoff (Ally , a thirty minute version that * Associate Professor of Law, Louisiana State University Law Center. I wish to thank Darlene C. Goring, Associate Professor of Law, Louisiana State University Law Center, for her thoughtful reading of the manuscript and her cogent and helpful comments on its content and N. Greg Smith, Professor of Law, Louisiana State University Law Center, for helpful comments and discussion of ethical rules. -

Small-Screen Courtrooms a Hit with Lawyers - Buffalo - Buffalo Business First

9/18/2018 Small-screen courtrooms a hit with lawyers - Buffalo - Buffalo Business First MENU Account FOR THE EXCLUSIVE USE OF [email protected] From the Buffalo Business First: https://www.bizjournals.com/buffalo/news/2018/09/17/small-screen-courtrooms-a-hit-with-lawyers.html Small-screen courtrooms a hit with lawyers Sep 17, 2018, 6:00am EDT For many, TV shows are an escape from reality. For attorneys, that’s no different – even when they’re watching lawyers on TV. “Better Call Saul” is the latest in a long line of TV shows about the legal profession. A prequel to AMC’s “Breaking Bad,” the show stars Bob Odenkirk as a crooked-at-times attorney named Jimmy McGill. “He’s a likable guy and you like his character,” said Patrick Fitzsimmons, senior associate at Hodgson Russ LLP in Buffalo. “It’s a great show. I think it’s the one BEN LEUNER/AMC show compared to the others where it’s not about a big firm.” “Better Call Saul” puts a new spin on legal drama as the slippery Jimmy McGill (played by Bob Odenkirk) Also a fan is Michael Benz, an associate at HoganWillig who recently returned to builds his practice. his native Buffalo after working in the Philadelphia public defender’s office and in his own practice as a criminal defense attorney. “(Odenkirk’s character is) the classic defense attorney who will do anything to make a buck or help his client,” Benz said, adding that he often binge-watches shows with his wife, Carla, an attorney in the federal public defender’s office in Buffalo. -

English Song Booklet

English Song Booklet SONG NUMBER SONG TITLE SINGER SONG NUMBER SONG TITLE SINGER 100002 1 & 1 BEYONCE 100003 10 SECONDS JAZMINE SULLIVAN 100007 18 INCHES LAUREN ALAINA 100008 19 AND CRAZY BOMSHEL 100012 2 IN THE MORNING 100013 2 REASONS TREY SONGZ,TI 100014 2 UNLIMITED NO LIMIT 100015 2012 IT AIN'T THE END JAY SEAN,NICKI MINAJ 100017 2012PRADA ENGLISH DJ 100018 21 GUNS GREEN DAY 100019 21 QUESTIONS 5 CENT 100021 21ST CENTURY BREAKDOWN GREEN DAY 100022 21ST CENTURY GIRL WILLOW SMITH 100023 22 (ORIGINAL) TAYLOR SWIFT 100027 25 MINUTES 100028 2PAC CALIFORNIA LOVE 100030 3 WAY LADY GAGA 100031 365 DAYS ZZ WARD 100033 3AM MATCHBOX 2 100035 4 MINUTES MADONNA,JUSTIN TIMBERLAKE 100034 4 MINUTES(LIVE) MADONNA 100036 4 MY TOWN LIL WAYNE,DRAKE 100037 40 DAYS BLESSTHEFALL 100038 455 ROCKET KATHY MATTEA 100039 4EVER THE VERONICAS 100040 4H55 (REMIX) LYNDA TRANG DAI 100043 4TH OF JULY KELIS 100042 4TH OF JULY BRIAN MCKNIGHT 100041 4TH OF JULY FIREWORKS KELIS 100044 5 O'CLOCK T PAIN 100046 50 WAYS TO SAY GOODBYE TRAIN 100045 50 WAYS TO SAY GOODBYE TRAIN 100047 6 FOOT 7 FOOT LIL WAYNE 100048 7 DAYS CRAIG DAVID 100049 7 THINGS MILEY CYRUS 100050 9 PIECE RICK ROSS,LIL WAYNE 100051 93 MILLION MILES JASON MRAZ 100052 A BABY CHANGES EVERYTHING FAITH HILL 100053 A BEAUTIFUL LIE 3 SECONDS TO MARS 100054 A DIFFERENT CORNER GEORGE MICHAEL 100055 A DIFFERENT SIDE OF ME ALLSTAR WEEKEND 100056 A FACE LIKE THAT PET SHOP BOYS 100057 A HOLLY JOLLY CHRISTMAS LADY ANTEBELLUM 500164 A KIND OF HUSH HERMAN'S HERMITS 500165 A KISS IS A TERRIBLE THING (TO WASTE) MEAT LOAF 500166 A KISS TO BUILD A DREAM ON LOUIS ARMSTRONG 100058 A KISS WITH A FIST FLORENCE 100059 A LIGHT THAT NEVER COMES LINKIN PARK 500167 A LITTLE BIT LONGER JONAS BROTHERS 500168 A LITTLE BIT ME, A LITTLE BIT YOU THE MONKEES 500170 A LITTLE BIT MORE DR. -

Alvin Ailey American Dance Theater

Tuesday through Friday, March 14 –17, 2017, 8pm Saturday, March 18, 2017, 2pm and 8pm Sunday, March 19, 2017, 3pm Zellerbach Hall Alvin Ailey American Dance Theater Alvin Ailey, Founder Judith Jamison, Artistic Director Emerita Robert Battle , Artistic Director Masazumi Chaya, Associate Artistic Director COMPANY MEMBERS Hope Boykin Jacquelin Harris Akua Noni Parker Jeroboam Bozeman Collin Heyward Danica Paulos Sean Aaron Carmon Michael Jackson, Jr. Belen Pereyra Elisa Clark Megan Jakel Jamar Roberts Sarah Daley Yannick Lebrun Samuel Lee Roberts Ghrai DeVore Renaldo Maurice Kanji Segawa Solomon Dumas Ashley Mayeux Glenn Allen Sims Samantha Figgins Michael Francis McBride Linda Celeste Sims Vernard J. Gilmore Rachael McLaren Constance Stamatiou Jacqueline Green Chalvar Monteiro Jermaine Terry Daniel Harder Fana Tesfagiorgis Matthew Rushing, Rehearsal Director and Guest Artist Bennett Rink, Executive Director Major funding for Alvin Ailey American Dance Theater is provided by the National Endowment for the Arts; the New York State Council on the Arts; the New York City Department of Cultural Affairs; American Express; Bank of America; BET Networks; Bloomberg Philanthropies; BNY Mellon; Delta Air Lines; Diageo, North America; Doris Duke Charitable Foundation; FedEx; Ford Foundation; Howard Gilman Foundation; The William R. Kenan, Jr. Charitable Trust; The Prudential Foundation; The SHS Foundation; The Shubert Foundation; Southern Company; Target; The Wallace Foundation; and Wells Fargo. These performances are made possible, in part, by Corporate -

BBC Radio 2 | Fri 01 Jan - Sat 31 Dec 2016 Between 00:00 and 24:00 Compared to 06 Jan 2017 Between 00:00 and 24:00

BBC Radio 2 | Fri 01 Jan - Sat 31 Dec 2016 between 00:00 and 24:00 Compared to 06 Jan 2017 between 00:00 and 24:00 Pos LW Artist Title Company Owner R. date Plays LW plays Trend 1 Justin Timberlake Can't Stop The Feeling RCA SME 06 May 2016 155 New -- 2 Lukas Graham 7 Years Warner Bros R.. WMG 23 Jun 2015 140 New -- 3 DNCE Cake By The Ocean Island UMG 15 Sep 2015 131 New -- 4 Coldplay Hymn For The Weekend Parlophone WMG 04 Dec 2015 108 New -- 5 Shadows, The Foot Tapper Columbia SME - 106 New -- 6 Travis 3 Miles High Caroline Inte.. UMG 26 Feb 2016 103 New -- 7 ABC Viva Love Virgin EMI UMG 08 Apr 2016 98 New -- 8 Sigma feat. Take That Cry 3beat Ind. 15 Jul 2016 97 New -- 9 Emeli Sandé Breathing Underwater Virgin EMI UMG 27 Oct 2016 95 New -- 9 Gwen Stefani Make Me Like You Interscope UMG 25 Mar 2016 95 New -- 9 Michael Bublé Nobody But Me Warner Bros R.. WMG 18 Aug 2016 95 New -- 12 ABC The Flames Of Desire Virgin EMI UMG 27 May 2016 94 New -- 12 Shaun Escoffery When The Love Is Gone Dome/MVKA Ind. 17 Jun 2016 94 New -- 12 Tom Odell Magnetised Columbia SME 14 Apr 2016 94 New -- 15 Jamie Lawson Cold In Ohio Atlantic WMG 16 Dec 2015 93 New -- 15 Joe & Jake You're Not Alone Sony CMG SME 23 Feb 2016 93 New -- 15 Rag'N'Bone Man Human Columbia SME 20 Jul 2016 93 New -- 18 Travis Animals Caroline Inte. -

Dan Blaze's Karaoke Song List

Dan Blaze's Karaoke Song List - By Artist 112 Peaches And Cream 411 Dumb 411 On My Knees 411 Teardrops 911 A Little Bit More 911 All I Want Is You 911 How Do You Want Me To Love You 911 More Than A Woman 911 Party People (Friday Night) 911 Private Number 911 The Journey 10 cc Donna 10 cc I'm Mandy 10 cc I'm Not In Love 10 cc The Things We Do For Love 10 cc Wall St Shuffle 10 cc Dreadlock Holiday 10000 Maniacs These Are The Days 1910 Fruitgum Co Simon Says 1999 Man United Squad Lift It High 2 Evisa Oh La La La 2 Pac California Love 2 Pac & Elton John Ghetto Gospel 2 Unlimited No Limits 2 Unlimited No Limits 20 Fingers Short Dick Man 21st Century Girls 21st Century Girls 3 Doors Down Kryptonite 3 Oh 3 feat Katy Perry Starstrukk 3 Oh 3 Feat Kesha My First Kiss 3 S L Take It Easy 30 Seconds To Mars The Kill 38 Special Hold On Loosely 3t Anything 3t With Michael Jackson Why 4 Non Blondes What's Up 4 Non Blondes What's Up 5 Seconds Of Summer Don't Stop 5 Seconds Of Summer Good Girls 5 Seconds Of Summer She Looks So Perfect 5 Star Rain Or Shine Updated 08.04.2015 www.blazediscos.com - www.facebook.com/djdanblaze Dan Blaze's Karaoke Song List - By Artist 50 Cent 21 Questions 50 Cent Candy Shop 50 Cent In Da Club 50 Cent Just A Lil Bit 50 Cent Feat Neyo Baby By Me 50 Cent Featt Justin Timberlake & Timbaland Ayo Technology 5ive & Queen We Will Rock You 5th Dimension Aquarius Let The Sunshine 5th Dimension Stoned Soul Picnic 5th Dimension Up Up and Away 5th Dimension Wedding Bell Blues 98 Degrees Because Of You 98 Degrees I Do 98 Degrees The Hardest