Community Media Narrowcasting in Uganda: an Assessment of Community Audio Towers

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

MUKONO BFP.Pdf

Local Government Budget Framework Paper Vote: 542 Mukono District Structure of Budget Framework Paper Foreword Executive Summary A: Revenue Performance and Plans B: Summary of Department Performance and Plans by Workplan C: Draft Annual Workplan Outputs for 2015/16 Page 1 Local Government Budget Framework Paper Vote: 542 Mukono District Foreword The District expects an annual budget of shs. 28,090,331,000 of which central grants contribute over 94.2% Donor funding 1.6% and local revenue 4.2%. The expected expenditure per department is as follows: Administration=3.8%, Finance= 4.6%, statutory bodies=3.4%, Production=8.9%, Health care= 10.8%, Education and sports= 57.1%, Works=3.8%, Water = 2.3%, Natural resource=1%, Community based=1.7%, Planning unit=2.2%, Internal audit=0 .4%. LUKE L. L. LOKUDA CHIEF ADMINISTRATIVE OFFICER MUKONO DISTRICT Page 2 Local Government Budget Framework Paper Vote: 542 Mukono District Executive Summary Revenue Performance and Plans 2014/15 2015/16 Approved Budget Receipts by End Proposed Budget September UShs 000's 1. Locally Raised Revenues 1,338,909 233,424 1,338,909 2a. Discretionary Government Transfers 2,860,770 715,193 2,860,770 2b. Conditional Government Transfers 25,300,550 6,174,496 25,300,550 2c. Other Government Transfers 2,759,364 1,256,460 1,734,554 3. Local Development Grant 677,694 169,423 677,694 4. Donor Funding 529,677 181,770 0 Total Revenues 33,466,963 8,730,765 31,912,477 Revenue Performance in the first quarter of 2014/15 Planned Revenues for 2015/16 Expenditure Performance and Plans 2014/15 -

Ministry of Education,Science,Technology And

Vote Performance Report and Workplan Financial Year 2015/16 Vote: 013 Ministry of Education, Science, Technology and Sports Structure of Submission QUARTER 3 Performance Report Summary of Vote Performance Cumulative Progress Report for Projects and Programme Quarterly Progress Report for Projects and Programmes QUARTER 4: Workplans for Projects and Programmes Submission Checklist Page 1 Vote Performance Report and Workplan Financial Year 2015/16 Vote: 013 Ministry of Education, Science, Technology and Sports QUARTER 3: Highlights of Vote Performance V1: Summary of Issues in Budget Execution This section provides an overview of Vote expenditure (i) Snapshot of Vote Releases and Expenditures Table V1.1 below summarises cumulative releases and expenditures by the end of the quarter: Table V1.1: Overview of Vote Expenditures (UShs Billion) Approved Cashlimits Released Spent by % Budget % Budget % Releases (i) Excluding Arrears, Taxes Budget by End by End End Mar Released Spent Spent Wage 11.218 9.015 9.015 8.648 80.4% 77.1% 95.9% Recurrent Non Wage 131.229 109.486 108.844 104.885 82.9% 79.9% 96.4% GoU 62.227 41.228 28.424 24.904 45.7% 40.0% 87.6% Development Ext Fin. 200.477 N/A 77.806 77.806 38.8% 38.8% 100.0% GoU Total 204.674 159.728 146.283 138.436 71.5% 67.6% 94.6% Total GoU+Ext Fin. (MTEF) 405.150 N/A 224.089 216.242 55.3% 53.4% 96.5% Arrears 0.642 N/A 0.642 0.553 100.0% 86.1% 86.1% (ii) Arrears and Taxes Taxes** 19.258 N/A 12.804 2.548 66.5% 13.2% 19.9% Total Budget 425.050 159.728 237.535 219.343 55.9% 51.6% 92.3% * Donor expenditure -

A Case of Mwanamugimu Nutrition Unit, Mulago National Referral

SIT Graduate Institute/SIT Study Abroad SIT Digital Collections Independent Study Project (ISP) Collection SIT Study Abroad Fall 2013 A Comparison of Malnutrition Causes and Treatments: A Case of Mwanamugimu Nutrition Unit, Mulago National Referral Hospital, Kampala District and Nakifuma Government Health Unit, Mukono District Berkley Singer SIT Study Abroad Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcollections.sit.edu/isp_collection Part of the Community-Based Research Commons, Community Health and Preventive Medicine Commons, Family, Life Course, and Society Commons, Health Services Research Commons, Inequality and Stratification Commons, Maternal and Child Health Commons, Place and Environment Commons, and the Public Health Education and Promotion Commons Recommended Citation Singer, Berkley, "A Comparison of Malnutrition Causes and Treatments: A Case of Mwanamugimu Nutrition Unit, Mulago National Referral Hospital, Kampala District and Nakifuma Government Health Unit, Mukono District" (2013). Independent Study Project (ISP) Collection. 1693. https://digitalcollections.sit.edu/isp_collection/1693 This Unpublished Paper is brought to you for free and open access by the SIT Study Abroad at SIT Digital Collections. It has been accepted for inclusion in Independent Study Project (ISP) Collection by an authorized administrator of SIT Digital Collections. For more information, please contact [email protected]. A Comparison of Malnutrition Causes and Treatments: A Case of Mwanamugimu Nutrition Unit, Mulago National Referral Hospital, Kampala District and Nakifuma Government Health Unit, Mukono District Berkley Singer Advisor: Dr. Jolly Kamugisha Academic Director: Dr. Charlotte Mafumbo Fall 2013 Acknowledgement: I would like to acknowledge Dr. Charlotte Mafumbo for all her hard work and dedication throughout the research process. She is an amazing worker and deserves all the praise in the world. -

October 21 2017 Thesis New Changes Tracked

The Status, Rights and Treatment of Persons with Disabilities within Customary Legal Frameworks in Uganda: A Study of Mukono District By David Brian Dennison BA (honours), MBA, JD (cum laude) (University of Georgia, USA) Thesis Presented for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy in the Department of Private TownLaw Faculty of Law UNIVERSITY OF CAPE TOWN Cape of Date of submission: 31 October 2017 Supervisor: Professor Chuma Himonga University Department of Private Law University of Cape Town The copyright of this thesis vests in the author. No quotation from it or information derivedTown from it is to be published without full acknowledgement of the source. The thesis is to be used for private study or non- commercial research purposes Capeonly. of Published by the University of Cape Town (UCT) in terms of the non-exclusive license granted to UCT by the author. University The copyright for this thesis rests with the University of Cape Town. No quotation from it or information derived from it is to be published without full acknowledgment of the source. The thesis is to be used for private study or non-commercial research purposes only. "ii ABSTRACT Thesis Title: The Status, Rights and Treatment of Persons with Disabilities within Customary Legal Frameworks in Uganda: A Study of Mukono District Submitted by: David Brian Dennison on 31 October 2017 This thesis addresses the question: How do customary legal frameworks impact the status, rights and treatment of persons with disabilities? It is motivated by two underlying premises. First, customary legal frameworks are highly consequential in Sub-Saharan contexts. -

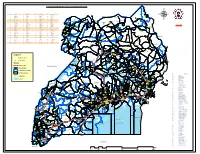

UGANDA: PLANNING MAP (Details)

IMU, UNOCHA Uganda http://www.ugandaclusters.ug http://ochaonline.un.org UGANDA: PLANNING MAP (Details) SUDAN NARENGEPAK KARENGA KATHILE KIDEPO NP !( NGACINO !( LOPULINGI KATHILE AGORO AGU FR PABAR AGORO !( !( KAMION !( Apoka TULIA PAMUJO !( KAWALAKOL RANGELAND ! KEI FR DIBOLYEC !( KERWA !( RUDI LOKWAKARAMOE !( POTIKA !( !( PAWACH METU LELAPWOT LAWIYE West PAWOR KALAPATA MIDIGO NYAPEA FR LOKORI KAABONG Moyo KAPALATA LODIKO ELENDEREA PAJAKIRI (! KAPEDO Dodoth !( PAMERI LAMWO FR LOTIM MOYO TC LICWAR KAPEDO (! WANDI EBWEA VUURA !( CHAKULYA KEI ! !( !( !( !( PARACELE !( KAMACHARIKOL INGILE Moyo AYUU POBURA NARIAMAOI !( !( LOKUNG Madi RANGELAND LEFORI ALALI OKUTI LOYORO AYIPE ORAA PAWAJA Opei MADI NAPORE MORUKORI GWERE MOYO PAMOYI PARAPONO ! MOROTO Nimule OPEI PALAJA !( ALURU ! !( LOKERUI PAMODO MIGO PAKALABULE KULUBA YUMBE PANGIRA LOKOLIA !( !( PANYANGA ELEGU PADWAT PALUGA !( !( KARENGA !( KOCHI LAMA KAL LOKIAL KAABONG TEUSO Laropi !( !( LIMIDIA POBEL LOPEDO DUFILE !( !( PALOGA LOMERIS/KABONG KOBOKO MASALOA LAROPI ! OLEBE MOCHA KATUM LOSONGOLO AWOBA !( !( !( DUFILE !( ORABA LIRI PALABEK KITENY SANGAR MONODU LUDARA OMBACHI LAROPI ELEGU OKOL !( (! !( !( !( KAL AKURUMOU KOMURIA MOYO LAROPI OMI Lamwo !( KULUBA Koboko PODO LIRI KAL PALORINYA DUFILE (! PADIBE Kaabong LOBONGIA !( LUDARA !( !( PANYANGA !( !( NYOKE ABAKADYAK BUNGU !( OROM KAABONG! TC !( GIMERE LAROPI PADWAT EAST !( KERILA BIAFRA !( LONGIRA PENA MINIKI Aringa!( ROMOGI PALORINYA JIHWA !( LAMWO KULUYE KATATWO !( PIRE BAMURE ORINJI (! BARINGA PALABEK WANGTIT OKOL KINGABA !( LEGU MINIKI -

Mukono District Local Government

MUKONO DISTRICT LOCAL GOVERNMENT P.O.BOX 110, MUKONO BID NOTICE UNDER OPEN DOMESTIC BIDDING, PRE-QUALIFICATION AND FRAME WORK CONTRACTS FOR F/Y 2021/2022 Mukono District Local government invites detailed applications from rehabilitation materials interested and competent firms/ companies for pre-qualification and Muko542/Supls/21-22/013 Supply of inert and gravel pack frame work contract for provision of works, services and supplies for Muko542/Srvcs/21-22/014 Repair and servicing of the drilling rig F/Y 2021/2022 as described below. Muko542/Srvcs/21-22/015 Test pumping, casting, installation of boreholes and water quality sampling. CATEGORY A – PREQUALIFICATION FOR SERVICES Muko542/Supls/21-22/016 Supply of the rig and compressor spare ACTIVITY CODE ACTIVITY DESCRIPTION parts. Muko542/Srvcs/21-22/0001 Property Valuation Muko542/Supls/21-22/017 Plumbing works and water supply Muko542/Srvcs/21-22/0002 Motor vehicle and motorcycle insurance connections Muko542/Srvcs/21-22/0003 Enforcement of revenue collection and Muko542/Supls/21-22/018 Supply of water quality reagents and management consumables Muko542/Srvcs/21-22/0004 Garbage collection and management Muko542/Supls/21-22/019 Supply of medical equipment and Muko542/Srvcs/21-22/0005 Car hire services reagents Muko542/Supls/21-22/020 Media and publication CATEGORY B – PREQUALIFICATION FOR WORKS Muko542/Supls/21-22/021 Supply of cleaning materials ACTIVITY CODE ACTIVITY DESCRIPTION Muko542/Wrks/21-22/0001 Construction and renovation of CATEGORY E- OPEN BIDDING buildings and civil works Muko542/Srvcs/21-22/00001 Property valuation of commercial building in Katosi TC, Ntenjeru Kisoga TC and Namataba TC CATEGORY C – PREQUALIFICATION FOR SUPPLIES ACTIVITY CODE ACTIVITY DESCRIPTION Bidding will be conducted in accordance with the Public Procurement Muko542/Supls/21-22/0001 Agricultural Equipment & Implements and disposal of Public Assets Act, 2003 of the Government of Uganda Muko542/Supls/21-22/0002 Entomological supplies and it’s open to all Bidders. -

Vote:542 Mukono District Quarter1

Local Government Quarterly Performance Report FY 2019/20 Vote:542 Mukono District Quarter1 Terms and Conditions I hereby submit Quarter 1 performance progress report. This is in accordance with Paragraph 8 of the letter appointing me as an Accounting Officer for Vote:542 Mukono District for FY 2019/20. I confirm that the information provided in this report represents the actual performance achieved by the Local Government for the period under review. Nkata. B. James Date: 05/12/2019 cc. The LCV Chairperson (District) / The Mayor (Municipality) 1 Local Government Quarterly Performance Report FY 2019/20 Vote:542 Mukono District Quarter1 Summary: Overview of Revenues and Expenditures Overall Revenue Performance Ushs Thousands Approved Budget Cumulative Receipts % of Budget Received Locally Raised Revenues 2,165,188 541,297 25% Discretionary Government 4,425,042 1,190,092 27% Transfers Conditional Government Transfers 35,247,076 9,611,327 27% Other Government Transfers 3,791,074 663,098 17% External Financing 256,500 42,410 17% Total Revenues shares 45,884,879 12,048,224 26% Overall Expenditure Performance by Workplan Ushs Thousands Approved Cumulative Cumulative % Budget % Budget % Releases Budget Releases Expenditure Released Spent Spent Administration 7,460,303 2,150,500 1,922,394 29% 26% 89% Finance 469,132 114,856 85,192 24% 18% 74% Statutory Bodies 1,007,284 252,999 177,696 25% 18% 70% Production and Marketing 2,330,532 595,709 469,467 26% 20% 79% Health 6,530,010 1,841,368 1,760,879 28% 27% 96% Education 24,190,088 6,039,281 5,341,989 -

Impact of the Black Twig Borer on Robusta Coffee in Mukono and Kayunga Districts, Central Uganda

Journal of Animal & Plant Sciences, 2009. Vol. 3, Issue 1: 163 - 169. Publication date: 15 May 2009, http://www.biosciences.elewa.org/JAPS; ISSN 2071 - 7024 JAPS Impact of the black twig borer on Robusta coffee in Mukono and Kayunga districts, central Uganda Egonyu JP 1§, Kucel P 1, Kangire A 1, Sewaya F 2. and Nkugwa C 2 1National Crops Resources Research Institute (NaCRRI)/Coffee Research Centre (COREC), P.O Box 185, Mukono, Uganda; Uganda Coffee Development Authority, P.O. Box 7267, Kampala, Uganda § Corresponding author email: [email protected] Key words: Black twig borer, coffee, incidence, damage 1 SUMMARY An outbreak of a “serious” pest of coffee was reported in Mukono and Kayunga districts in central Uganda in December 2008. In response, a survey was carried out in the two districts to determine the identity, spread, incidence and damage caused by the pest. The pest was preliminarily identified as the black twig borer, Xylosandrus compactus (Eichhoff), which was found on coffee in both districts infesting 37.5% of the surveyed Robusta coffee farms. The infestation in Mukono was higher than in Kayunga, being 50 and 8.3%, respectively. The percentage of trees attacked (incidence) in the two districts was 21.2, with 3.7% of their twigs bored (damaged). Mukono district had a much higher incidence (35.3%) and damage (4.9%) compared to Kayunga with 0.8% for both parameters. The most serious damage was recorded in Namuganga and Nabbaale subcounties in Mukono district, the apparent epicentre of the outbreak. It was evident that the pest was spreading to other subcounties surveyed within and outside Mukono district. -

Croc's 05.Qxd

CLASSIFIED ADVERTS NEW VISION, Tuesday, June 5, 2012 35 RABBAI “With Trust & Honesty” Sema Properties Ltd Tested & Reliable Housing HOSSANA REAL .....we settle you RABBAI REAL ESTATES HERITAGE SITES LTD Vacancies Vacancies SPECIAL OFFER 10% DISCOUNT RentWell surveyed plots with ready Sema Properties Ltd ESTATES LTD RentON ALL PLOTS “Your Home, Your Prestige” Mailo Land Titles. 1. NAKAWUKA Entebbe Road Real Estate Developers, CANAAN SITES UP TO 30TH JUNE, 2012 CCANAANANAAN SSITESITES Surveyors & Contractors PLANNED PLOTS WITH WELL PLANNED AND ORGANISED with green Environment - ZION PLOTS WITH TITLES, “FIRST STEP TO NEW HOME” 1. GAYAZA-ZIROBWE 50 x 100ft = 4.5m Well planned plots with Mailo land PRIVATE MAILO LAND ESTATES WITH MAILO LAND TITLES, titles at hand. Water & power and accessible SEVERAL PLOTS WITH MAILO WATER & POWER. 1 Km from tarmac 100 x 100ft = 9m TITLES LAND TITLES AT HAND. 50 x 100ft - 3.6m 1. MUKONO-KAYANJA with public means. 1. GAYAZA KIRA ROYAL ESTATE 2. MATUGGA Migadde. 1. KAKIRI-MWERA PHASE II 1. KAKIRI-Hoima Road 50 x 100 ft - 2.3m (Cash) 50 x 100ft - 2.5m All tarmac from Kampala to the 100 x 100ft - 7.2m Good view of Kampala & 1. MATUGA-KIWEBWA 50ft x 100ft - 2.5m Estate with mailo land titles. 50 x 100 ft - 2.6m (Instalments) 100 x 100ft - 5m 2. GAYAZA RD, near main road 100 x 100 ft - 4.6m ESTATE 100ft x 100ft - 5m 50 x 100ft - 10m & 14m 2. MUKONO-Kayunga Road, 50 X 100ft 2.5m & 3.5m Live like Vice President NAKASAJJA 50 x 100ft = 3.5m 2. -

Legend " Wanseko " 159 !

CONSTITUENT MAP FOR UGANDA_ELECTORAL AREAS 2016 CONSTITUENT MAP FOR UGANDA GAZETTED ELECTORAL AREAS FOR 2016 GENERAL ELECTIONS CODE CONSTITUENCY CODE CONSTITUENCY CODE CONSTITUENCY CODE CONSTITUENCY 266 LAMWO CTY 51 TOROMA CTY 101 BULAMOGI CTY 154 ERUTR CTY NORTH 165 KOBOKO MC 52 KABERAMAIDO CTY 102 KIGULU CTY SOUTH 155 DOKOLO SOUTH CTY Pirre 1 BUSIRO CTY EST 53 SERERE CTY 103 KIGULU CTY NORTH 156 DOKOLO NORTH CTY !. Agoro 2 BUSIRO CTY NORTH 54 KASILO CTY 104 IGANGA MC 157 MOROTO CTY !. 58 3 BUSIRO CTY SOUTH 55 KACHUMBALU CTY 105 BUGWERI CTY 158 AJURI CTY SOUTH SUDAN Morungole 4 KYADDONDO CTY EST 56 BUKEDEA CTY 106 BUNYA CTY EST 159 KOLE SOUTH CTY Metuli Lotuturu !. !. Kimion 5 KYADDONDO CTY NORTH 57 DODOTH WEST CTY 107 BUNYA CTY SOUTH 160 KOLE NORTH CTY !. "57 !. 6 KIIRA MC 58 DODOTH EST CTY 108 BUNYA CTY WEST 161 OYAM CTY SOUTH Apok !. 7 EBB MC 59 TEPETH CTY 109 BUNGOKHO CTY SOUTH 162 OYAM CTY NORTH 8 MUKONO CTY SOUTH 60 MOROTO MC 110 BUNGOKHO CTY NORTH 163 KOBOKO MC 173 " 9 MUKONO CTY NORTH 61 MATHENUKO CTY 111 MBALE MC 164 VURA CTY 180 Madi Opei Loitanit Midigo Kaabong 10 NAKIFUMA CTY 62 PIAN CTY 112 KABALE MC 165 UPPER MADI CTY NIMULE Lokung Paloga !. !. µ !. "!. 11 BUIKWE CTY WEST 63 CHEKWIL CTY 113 MITYANA CTY SOUTH 166 TEREGO EST CTY Dufile "!. !. LAMWO !. KAABONG 177 YUMBE Nimule " Akilok 12 BUIKWE CTY SOUTH 64 BAMBA CTY 114 MITYANA CTY NORTH 168 ARUA MC Rumogi MOYO !. !. Oraba Ludara !. " Karenga 13 BUIKWE CTY NORTH 65 BUGHENDERA CTY 115 BUSUJJU 169 LOWER MADI CTY !. -

Vote: 542 Mukono District Structure of Budget Framework Paper

Local Government Budget Framework Paper Vote: 542 Mukono District Structure of Budget Framework Paper Foreword Executive Summary A: Revenue Performance and Plans B: Summary of Department Performance and Plans by Workplan C: Draft Annual Workplan Outputs for 2013/14 Page 1 Local Government Budget Framework Paper Vote: 542 Mukono District Foreword The annual work plan and budget of the year 2013/14 has been out of deliberate efforts by the Technical and Political Leadership. The 2013/2014 Annual work plan and Budget provides a great opportunity for social economic advancement of the people of Mukono District. The planning and Budgeting process has taken a sizeable amount of time and financial resources. I therefore extend my appreciation to Government of Uganda and the private sector for their contribution to the making of this BFP. This plan is a strategic tool in the struggle to get the people of Mukono District out of absolute poverty. The investment areas covered aim at consolidating past achievements which address Primary Education, Primary Health Care, Modernization of Agriculture, etc. On average there has been increase in funding of key production sectors e.g. Agriculture and related activities together with empowering disadvantaged groups. The aim has been to capture pertinent issues that have direct bearing to household incomes. I would like to thank all Heads of Departments especially those who made presentations, the Lower Local Governments Councils, NGOs, delegates who participated in the district plan/ Budget conference and the district council for the roles they have played. In a special way I wish to thank the central Government for funding programmes and investments for 2012/2013. -

PBU AGENTS Central Region

PBU AGENTS Central Region Name of Agent or Outlet Place of Business District Abusha Junior (U) Ltd Bombo Luweero Parmer Financial Services Ltd Kapeeka Nakaseke Q&A Education and Management Consultancy Bombo Luweero Holy Saints Uganda Limited Bombo T/C Luweero Danortry Financial Link (U) Ltd Opposite PostBank Bombo Branch Luwero Dithcom Trading Co. Limited Opposite Centenary Bank ATM Luwero Glarison Technologies Limited Near the Barracks Luwero Nasu Express Outlet Bombo, near SR Fuel Station Luwero Nasu Express Outlet Opposite Bombo UPDF Play ground Luwero Uganda Post Limited Kyambogo Kampala Uganda Post Limited Nakawa Kampala NIK Tel Traders Nakawa Kampala Prime Secretarial Services Luzira Stage 6 Kampala ESSIE. RE Classic Fashions Biina Mutungo Kampala Nandudu Babra Kireka Wakiso Blessed Mina General Merchandise Kireka Wakiso Niktel Traders Pioneer Mall Kampala 6 GS Money Point Kireka Kampala Cinemax General Hardware Bweyogerere Wakiso Ariong Enterprises Mutungo Kampala Isip Connections Ltd Bugolobi Kampala Kireka BodaBoda Police Stage Co-Operative Kireka Kampala Savings and Credit Society Limited Chelanasta Cash Point Solutions Jinja Highway, Mukono Mukono Milly's Laundry Opposite UCU Main Gate Mukono Rana Phones 83 Enterprises Opp Kirinya Shopping Centre Wakiso Boadaph Financial Services Limited Sports Pro Hostel. Kampala Jeba (U) Limited Cwa 2 Street Kampala Tusaboomu Enterprises Ltd URA building, Nakawa Kampala Alpha Immanuel's Cash Point Najeera Road, Bweyogerere Wakiso Beulah Business Center Biina Road, Kunya Stage Kampala Kyobe