Karel Burian – the Guest of Budapest (1913–1924)

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

English Translation of the German by Tom Hammond

Richard Strauss Susan Bullock Sally Burgess John Graham-Hall John Wegner Philharmonia Orchestra Sir Charles Mackerras CHAN 3157(2) (1864 –1949) © Lebrecht Music & Arts Library Photo Music © Lebrecht Richard Strauss Salome Opera in one act Libretto by the composer after Hedwig Lachmann’s German translation of Oscar Wilde’s play of the same name, English translation of the German by Tom Hammond Richard Strauss 3 Herod Antipas, Tetrarch of Judea John Graham-Hall tenor COMPACT DISC ONE Time Page Herodias, his wife Sally Burgess mezzo-soprano Salome, Herod’s stepdaughter Susan Bullock soprano Scene One Jokanaan (John the Baptist) John Wegner baritone 1 ‘How fair the royal Princess Salome looks tonight’ 2:43 [p. 94] Narraboth, Captain of the Guard Andrew Rees tenor Narraboth, Page, First Soldier, Second Soldier Herodias’s page Rebecca de Pont Davies mezzo-soprano 2 ‘After me shall come another’ 2:41 [p. 95] Jokanaan, Second Soldier, First Soldier, Cappadocian, Narraboth, Page First Jew Anton Rich tenor Second Jew Wynne Evans tenor Scene Two Third Jew Colin Judson tenor 3 ‘I will not stay there. I cannot stay there’ 2:09 [p. 96] Fourth Jew Alasdair Elliott tenor Salome, Page, Jokanaan Fifth Jew Jeremy White bass 4 ‘Who spoke then, who was that calling out?’ 3:51 [p. 96] First Nazarene Michael Druiett bass Salome, Second Soldier, Narraboth, Slave, First Soldier, Jokanaan, Page Second Nazarene Robert Parry tenor 5 ‘You will do this for me, Narraboth’ 3:21 [p. 98] First Soldier Graeme Broadbent bass Salome, Narraboth Second Soldier Alan Ewing bass Cappadocian Roger Begley bass Scene Three Slave Gerald Strainer tenor 6 ‘Where is he, he, whose sins are now without number?’ 5:07 [p. -

Chronology 1916-1937 (Vienna Years)

Chronology 1916-1937 (Vienna Years) 8 Aug 1916 Der Freischütz; LL, Agathe; first regular (not guest) performance with Vienna Opera Wiedemann, Ottokar; Stehmann, Kuno; Kiurina, Aennchen; Moest, Caspar; Miller, Max; Gallos, Kilian; Reichmann (or Hugo Reichenberger??), cond., Vienna Opera 18 Aug 1916 Der Freischütz; LL, Agathe Wiedemann, Ottokar; Stehmann, Kuno; Kiurina, Aennchen; Moest, Caspar; Gallos, Kilian; Betetto, Hermit; Marian, Samiel; Reichwein, cond., Vienna Opera 25 Aug 1916 Die Meistersinger; LL, Eva Weidemann, Sachs; Moest, Pogner; Handtner, Beckmesser; Duhan, Kothner; Miller, Walther; Maikl, David; Kittel, Magdalena; Schalk, cond., Vienna Opera 28 Aug 1916 Der Evangelimann; LL, Martha Stehmann, Friedrich; Paalen, Magdalena; Hofbauer, Johannes; Erik Schmedes, Mathias; Reichenberger, cond., Vienna Opera 30 Aug 1916?? Tannhäuser: LL Elisabeth Schmedes, Tannhäuser; Hans Duhan, Wolfram; ??? cond. Vienna Opera 11 Sep 1916 Tales of Hoffmann; LL, Antonia/Giulietta Hessl, Olympia; Kittel, Niklaus; Hochheim, Hoffmann; Breuer, Cochenille et al; Fischer, Coppelius et al; Reichenberger, cond., Vienna Opera 16 Sep 1916 Carmen; LL, Micaëla Gutheil-Schoder, Carmen; Miller, Don José; Duhan, Escamillo; Tittel, cond., Vienna Opera 23 Sep 1916 Die Jüdin; LL, Recha Lindner, Sigismund; Maikl, Leopold; Elizza, Eudora; Zec, Cardinal Brogni; Miller, Eleazar; Reichenberger, cond., Vienna Opera 26 Sep 1916 Carmen; LL, Micaëla ???, Carmen; Piccaver, Don José; Fischer, Escamillo; Tittel, cond., Vienna Opera 4 Oct 1916 Strauss: Ariadne auf Naxos; Premiere -

Karel Burian and Hungary Research Director: Anna Dalos Phd Liszt Ferenc Academy of Music Doctoral School No

DLA Theses Ferenc János Szabó Karel Burian and Hungary Research director: Anna Dalos PhD Liszt Ferenc Academy of Music Doctoral School No. 28 for the History of Art and Culture Budapest 2011 I. Antecedents of the research Karel Burian was one of the best tenors of the first two decades of the twentieth century. The authors of his biographies always mention his Wagner roles – mainly Tristan – and his long presence in New York, and primarily the world premiere of Salome by Richard Strauss, when he played the role of Herod to much acclaim. His reputation and popularity might be measured against those of Enrico Caruso. Burian was first engaged in Budapest as a young but already well- known Wagner-tenor, he worked there for one year as a member of the Opera House, then later as guest singer regularly until his death. He was likely the most influential operatic world star in Budapest at the beginning of the twentieth century, and was the founder and for many years the only intended representative of the Heldentenor role in Hungary. He primarily sang Wagner operas, but there was also a Hungarian opera on his repertoire in Budapest. A study of his activities in Hungary contributes to our knowledge of Hungarian opera life, and Burian’s whole career affected the cultural history of the period because of his frequent guest appearances in Budapest. Burian’s Budapest activity had a great influence on the young composers of that time, most notably on Béla Bartók and Zoltán Kodály as well. There is a relatively large amount of literature about Burian, mostly in Czech, English and German. -

April 1911) James Francis Cooke

Gardner-Webb University Digital Commons @ Gardner-Webb University The tudeE Magazine: 1883-1957 John R. Dover Memorial Library 4-1-1911 Volume 29, Number 04 (April 1911) James Francis Cooke Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.gardner-webb.edu/etude Part of the Composition Commons, Ethnomusicology Commons, Fine Arts Commons, History Commons, Liturgy and Worship Commons, Music Education Commons, Musicology Commons, Music Pedagogy Commons, Music Performance Commons, Music Practice Commons, and the Music Theory Commons Recommended Citation Cooke, James Francis. "Volume 29, Number 04 (April 1911)." , (1911). https://digitalcommons.gardner-webb.edu/etude/568 This Book is brought to you for free and open access by the John R. Dover Memorial Library at Digital Commons @ Gardner-Webb University. It has been accepted for inclusion in The tudeE Magazine: 1883-1957 by an authorized administrator of Digital Commons @ Gardner-Webb University. For more information, please contact [email protected]. TWO PIANOS THE ETUDE FOUR HANDS New Publications The following ensemble pieces in- S^s?^yssL*aa.‘Sffi- Anthems of Prayer and Life Stories of Great nai editions, and some of the latest UP-TO-DATE PREMIUMS Sacred Duets novelties are inueamong to addthe WOnumberrks of For All Voices &nd General Use Praise Composers OF STANDARD QUALITY A MONTHLY JOURNAL FOR THE MUSICIAN, THE MUSIC STUDENT, AND ALL MUSIC LOVERS. sis Edited by JAMES FRANCIS COOKE Subscription Price, $1.60 per jeer In United States Alaska, Cuba, Po Mexico, Hawaii, Pb’”—1— "-“-“* *k- "•* 5 In Canada, »1.7t STYLISH PARASOLS FOUR DISTINCT ADVANCE STYLES REMITTANCES should be made by post-offlee t No. -

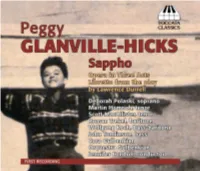

Toccata Classics TOCC0154-55 Notes

Peggy Glanville-Hicks and Lawrence Durrell discuss Sappho, play through the inished piano score Greece, 1963 Comprehensive information on Sappho and foreign-language translations of this booklet can be found at www.sappho.com.au. 2 Cast Sappho Deborah Polaski, soprano Phaon Martin Homrich, tenor Pittakos Scott MacAllister, tenor Diomedes Roman Trekel, baritone Minos Wolfgang Koch, bass-baritone Kreon John Tomlinson, bass Chloe/Priestess Jacquelyn Wagner, soprano Joy Bettina Jensen, soprano Doris Maria Markina, mezzo soprano Alexandrian Laurence Meikle, baritone Orquestra Gulbenkian Coro Gulbenkian Jennifer Condon, conductor Musical Preparation Moshe Landsberg English-Language Coach Eilene Hannan Music Librarian Paul Castles Chorus-Master Jorge Matta 3 CD1 Act 1 1 Overture 3:43 Scene 1 2 ‘Hurry, Joy, hurry!’... ‘Is your lady up? Chloe, Joy, Doris, Diomedes, Minos 4:14 3 ‘Now, at last you are here’ Minos, Sappho 6:13 4 Aria – Sappho: ‘My sleep is fragile like an eggshell is’ Sappho, Minos 4:17 5 ‘Minos!’ Kreon, Minos, Sappho 5:14 6 ‘So, Phaon’s back’ Minos, Sappho, Phaon 3:19 7 Aria – Phaon: ‘It must have seemed like that to them’ Phaon, Minos, Sappho 4:33 8 ‘Phaon, how is it Kreon did not ask you to stay’ Sappho, Phaon, Minos 2:24 Scene 2 – ‘he Symposium’ 9 Introduction... ‘Phaon has become much thinner’... Song with Chorus: he Nymph in the Fountain Minos, Sappho, Chorus 6:22 10 ‘Boy! Bring us the laurel!’... ‘What are the fortunes of the world we live in?’ Diomedes, Sappho, Minos, Kreon, Phaon, Alexandrian, Chorus 4:59 11 ‘Wait, hear me irst!’... he Epigram Contest Minos, Diomedes, Sappho, Chorus 2:55 12 ‘Sappho! Sappho!’.. -

6.5 X 11 Double Line.P65

Cambridge University Press 978-0-521-87392-5 - Never Sang for Hitler: The Life and Times of Lotte Lehmann, 1888-1976 Michael H. Kater Index More information Index 8 [Acht] Uhr-Blatt, Vienna, 56 Auguste Victoria, ex-queen of Portugal, 137 Abessynians, 273 Auguste Viktoria, Empress, 3, 9 Abravanel, Maurice, 207, 259–61, 287, 298 Austrian Honor Cross First Class, 278 Academy Awards, Hollywood, 232, 236 Austrian Republic, 44, 48, 51, 57, 64–66, 77, Adler, Friedrich, 38 85, 94, 97–99, 166, 307–8 Adolph, Paul, 110–11 Austrian State Theaters, 220 Adventures at the Lido, 234 Austrofascism, 94, 166–69, 308 Agfa company, 185 Aida, 266, 276 Bachur, Max, 15, 18–21, 28, 30–31, 33, Albert Hall, London, 117 42–43 Alceste, 269 Baker, Janet, 251 Alda, Frances, 68 Baker, Josephine, 94 Aldrich, Richard, 69 Baklanoff, Georges, 43 Alexander, king of Yugoslavia, 170 Ballin, Albert, 16, 30, 77, 304 Alice in Wonderland, 193 Balogh, Erno,¨ 147–49, 151, 158, 164, Alien Registration Act, 211 180–81 Allen, Fred, 230 Bampton, Rose, 183, 206, 245 Allen, Judith, 253 Banklin oil refinery, Santa Barbara, 212 Althouse, Paul, 174 Barnard College, Columbia University, New Altmeyer, Jeannine, 261 York, 151 Alvin Theater, New York, 204 Barsewisch, Bernhard von, 1, 13, 35, 285, Alwin, Karl, 102, 106–7, 189, 196 298, 302, 319n172, 343n269 American Committee for Christian German Barsewisch, Elisabeth von, nee´ Gans Edle zu Refugees, 211 Putlitz, 13, 82, 285, 295 American Legion, 68 Bartels, Elise, 11, 14 An die ferne Geliebte, 217 Barthou, Louis, 170 Anderson, Bronco Bill, 198 -

A Opera Catalogue Sectio#42336

Opera Operetta Music Theatre Supplement 2009 www.boosey.com/opera Opera Operetta Music Theatre Chamber Opera Musicals Stageworks for Young Audiences Stageworks for Young Performers from Boosey & Hawkes Bote & Bock Anton J. Benjamin Supplement 2009 Edited by David Allenby Cover illustrations: John Adams: Doctor Atomic Penny Woolcock’s production for the Metropolitan Opera and English National Opera (2008) with Gerald Finley as Oppenheimer Photo: © 2008 Ken Howard/Metropolitan Opera Detlev Glanert: Caligula Christian Pade’s world premiere production for Oper Frankfurt (2006) with Ashley Holland (Caligula) Photo: Monika Rittershaus Unsuk Chin: Alice in Wonderland Achim Freyer’s world premiere production for the Bavarian State Opera (2007) with Sally Matthews (Alice) Photo: Wilfried Hösl Jacques Offenbach: Les Fées du Rhin Vocal score in the Offenbach Edition Keck (OEK) published by Boosey & Hawkes / Bote & Bock Harrison Birtwistle: The Minotaur Stephen Langridge’s world premiere production for The Royal Opera in London (2008) with John Tomlinson (The Minotaur) and Johan Reuter (Theseus) Photo: Bill Cooper Michel van der Aa: The Book of Disquiet Still from the composer’s video for his world premiere production for Linz 2009 European Capital of Culture (2009) with Klaus Maria Brandauer Photo: Michel van der Aa Published by Boosey & Hawkes Music Publishers Limited Aldwych House 71–91 Aldwych London WC2B 4HN www.boosey.com an company © Copyright 2009 Boosey & Hawkes Music Publishers Ltd Printed in England by Halstan & Co Ltd, Amersham, Bucks Designed and typeset by David J Plumb ARCA PPSTD ISBN 978-0-85162-599-7 Contents 4 Introduction 5 Abbreviations 6 Catalogue 52 Addenda 55 Title Index 56 Boosey & Hawkes Addresses Introduction This 2009 Supplement contains works added since the publication of the 2004 Boosey & Hawkes Opera Catalogue. -

Opera Vocal Scores 76 Opera Full Scores 78 Opera Librettos 81 Opera Chorus Parts

61 MUSICOpera DISPATCH 62 The Orchestra Accompaniment Series 63 Opera Aria Collections 67 Cantolopera Series 68 Opera Vocal Scores 76 Opera Full Scores 78 Opera Librettos 81 Opera Chorus Parts 2006 62 THE ORCHESTRA ACCOMPANIMENT SERIES Recorded in Prague with the Czech Symphony Orchestra. The CDs in these packs contain two versions of each selection: one with a singer, and one with orchestra accompaniment only. All books in the series contain historical and plot notes about each opera, operetta or show, and piano/vocal reductions of the music. The singers heard on these recordings are top professionals from Covent Garden, English National Opera, and other main stages. 3 ARIAS FOR BARITONE/BASS Includes “Largo al foctotum” from Il barbiere di siviglia, “Votre toast, je peux vous le rendre (Toreador Song)” from Carmen, and “Madamina! Il catologo e questo” from Don Giovanni. ______00740061 Book/CD Pack .................................................................................$14.95 3 FAMOUS TENOR ARIAS Includes “Che gelida manina” from La Boheme, “La donna e mobile” from Rigoletto, and “Nessun dorma!” from Turandot. ______00740060 Book/CD Pack ..................................................................................$14.95 3 PUCCINI ARIAS FOR SOPRANO Includes “Quando men vo,” from La Boheme, “O mio babbino caro,” from Gianni Schicchi, and “Un bel di vedremo,” from Madama Butterfly. ______00740058 Book/CD Pack ..................................................................................$14.95 3 SEDUCTIVE ARIAS FOR MEZZO-SOPRANO Includes “Habanera” and “Seguidilla” from Carmen and “Mon coeur s’ouvre a ta voix” from Samson et dalila. ______00740059 Book/CD Pack ..................................................................................$14.95 BROADWAY – FULL DRESS PERFORMANCE Includes: Cabaret • If I Loved You • You’ll Never Walk Alone • People Will Say We’re in Love • Can’t Help Lovin’ Dat Man • Climb Ev’ry Mountain • Edelweiss • The Sound of Music • I’m Gonna Wash That Man Right Outa My Hair. -

12" Ejslp Issues

VOCAL 78 rpm Discs JOHN O’SULLIVAN [t] 4390. 10” Red acous. Spanish Regal (Columbia) RS 5030 [70601/70694]. OTELLO: Esultate! / OTELLO: Niun mi tema (Verdi). Cons. 2. $25.00. 4290. 10” Maroon acous. Eng. Columbia D5372 [B514/B532]. WILLIAM TELL: O muto asil (Rossini) / CARMEN: Romanza del fiore (Bizet). Cons. 2. $25.00. 4403. 10: Red acous. Eng. Columbia D12458 [B541/B549]. LES HUGUENOTS: Stringe il periglio (Meyerbeer). Two sides. With DORA DE GIOVANNI [s]. O’Sullivan’s phenomenal top register heard here at full cry. Excellent surfaces. Few lightest mks., cons. 2. $35.00. 4264. 10” Red acous. Eng. Columbia D12459 [B518/B532]. HUGUENOTS: Bianca al par (Meyerbeer) / CARMEN: Romanza del fior (Bizet). Cons. 2. $25.00. 4953. 10” Blue elec. PW Eng. Columbia D1573 [WA3564/WA3562]. IL TROVATORE: Ah si, ben mio / IL TROVATORE: Di quella pira (Verdi). Just about 1-2. $15.00. MARIA PIA PAGLIARINI [s]. Modina, 1902-1935. A pupil of Vezzani and Boninsegna, Pagliarini made her debut in 1921 as Nedda in Pagliacci and retired in 1930 after marrying conductor Antonio Fugazzola. Her final performance seems to have been Leonora in Il Trovatore at Milan’s Teatro dal Verme. See: ALESSANDRO BONCI. ESTHER PALLISER (or PALLISSER) [s]. Germantown, PA, 1872 - ? , She was taught by her musician parents and then studied further in Europe. Her operatic debut was in Rouen as Marguerite in Faust. This was followed by work with the D’Oyly Carte Opera Company in 1890. Her career included other Gilbert and Sullivan performances and tours, concerts, music festivals and grand opera at Covent Garden and Drury Lane. -

Czech Music in Nebraska

Czech Music in Nebraska Ceska Hudba v Nebrasce OUR COVER PICTURE The Pavlik Band of Verdigre, Nebraska, was organized in 1878 by the five Pavlik brothers: Matej, John, Albert, Charles and Vaclav. Mr. Vaclav Tomek also played in the band. (Photo courtesy of Edward S. Pavlik, Verdigre, Neraska). Editor Vladimir Kucera Co-editor DeLores Kucera Copyright 1980 by Vladimir Kucera DeLores Kucera Published 1980 Bohemians (Czechs) as a whole are extremely fond of dramatic performances. One of their sayings is “The stage is the school of life.” A very large percentage are good musicians, so that wherever even a small group lives, they are sure to have a very good band. Ruzena Rosicka They love their native music, with its pronounced and unusual rhythm especially when played by their somewhat martial bands. A Guide to the Cornhusker State Czechs—A Nation of Musicians An importantCzechoslovakian folklore is music. Song and music at all times used to accompany man from the cradle to the grave and were a necessary accompaniment of all important family events. The most popular of the musical instruments were bagpipes, usually with violin, clarinet and cembalo accompaniment. Typical for pastoral soloist music were different types of fifes and horns, the latter often monstrous contraptions, several feet long. Traditional folk music has been at present superseded by modern forms, but old rural musical instruments and popular tunes have been revived in amateur groups of folklore music or during folklore festivals. ZLATE CESKE VZPOMINKY GOLDEN CZECH MEMORIES There is an old proverb which says that every Czech is born, not with a silver spoon in his mouth, but with a violin under his pillow. -

Space, Time, Tradition Studies Undertaken at the Doctoral School of the Budapest Liszt Academy

Space, time, tradition Studies undertaken at the Doctoral School of the Budapest Liszt Academy Edited by Péter Bozó Tér, idő, hagyomány-ang-1.indd 1 2013.12.05. 20:02:56 Tereido_cover_final.indd 9 12/5/13 1:04 PM Tér, idő, hagyomány-ang-1.indd 400 2013.12.05. 20:05:27 Space, time, tradition Studies undertaken at the Doctoral School of the Budapest Liszt Academy Edited by Péter Bozó Tér, idő, hagyomány-ang-2.indd 3 2013.12.06. 13:35:05 Tereido_cover_final.indd 9 12/5/13 1:04 PM First published in Hungary in 2013 by Rózsavölgyi & Co (founded 1850) H–1052 Budapest, Szervita tér 5. Copyright © 2013 András Batta, Péter Bozó, Anna Dalos, Soma Dinyés, Gabriella Gilányi, Balázs Horváth, Nóra Keresztes, Andrea Kovács, Veronika Kusz, Judit Rajk, Anna Scholz, Ferenc János Szabó, Boglárka Várkonyiné Terray Edited by Péter Bozó The book was published with the support of European Union and with the co-financing of European Social Fund. The cover design is based on a page from a twelfth-century copy of Boethius’ treatise on music De musica. Managing editor: Gergely Fazekas Cover design: Ferenc Szabó Technical manager: Julianna Rácz Pre-press preparation: Cirmosné ISBN 978-615-5062-13-1 ISSN 2064-3780 All rights reserved. No part of this book shall be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted by any means – electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording, or otherwise – without written permission from the publisher. [email protected] http://rozsavolgyi.hu Printed in 2013 by Prime Rate Ltd. Managing director: Péter Tomcsányi Tér, idő, hagyomány-ang-1.indd 4 2013.12.05. -

19 February 2020

19 February 2020 12:01 AM Heinrich Ignaz Franz von Biber (1644-1704) Sonata no 1 à 8, from sonatae tam aris, quam aulis servientes (1676) Collegium Aureum DEWDR 12:06 AM Anonymous, Pedro Memelsdorff (arranger), Andreas Staier (arranger) Three tunes to John Playford's 'Dancing Master' Pedro Memelsdorff (recorder), Andreas Staier (harpsichord) DEWDR 12:11 AM Antonin Dvorak (1841-1904) Slavonic Dance in E minor, Op 46 no 2 James Anagnoson (piano), Leslie Kinton (piano) CACBC 12:17 AM Oskar Morawetz (1917-2007) Overture on a Fairy Tale Edmonton Symphony Orchestra, Uri Mayer (conductor) CACBC 12:28 AM Joaquín Turina (1882-1949) Circulo, Op 91 John Harding (violin), Stefan Metz (cello), Daniel Blumenthal (piano) NLNOS 12:39 AM Fryderyk Chopin (1810-1849), Stefan Witwicki (author), Bohdan Zaleski (author), Wincentry Pol (author) Six Songs from Polish Songs, Op 74 Marika Schonberg (soprano), Roland Pontinen (piano) SESR 12:57 AM Carl Philipp Emanuel Bach (1714-1788) Sonata in G minor Wq.88 for viola da gamba & harpsichord Friederike Heumann (viola da gamba), Dirk Borner (harpsichord) PLPR 01:19 AM Edward Elgar (1857-1934) 4 Choral Songs, Op 53 BBC Symphony Chorus, Stephen Jackson (conductor) GBBBC 01:34 AM Gioachino Rossini (1792-1868) String Sonata no 5 in E flat major Camerata Bern CHSRI 01:48 AM Fryderyk Chopin (1810-1849) Ballade for piano no 4 in F minor, Op 52 Khatia Buniatishvili (piano) PLPR 02:01 AM Ludwig van Beethoven (1770-1827) Coriolan - overture, Op 62 Oslo Philharmonic Orchestra, Andre Previn (conductor) NONRK 02:10 AM Wolfgang