Salome Ever and Never the Same

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Rise of the Tenor Voice in the Late Eighteenth Century: Mozart’S Opera and Concert Arias Joshua M

University of Connecticut OpenCommons@UConn Doctoral Dissertations University of Connecticut Graduate School 10-3-2014 The Rise of the Tenor Voice in the Late Eighteenth Century: Mozart’s Opera and Concert Arias Joshua M. May University of Connecticut - Storrs, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://opencommons.uconn.edu/dissertations Recommended Citation May, Joshua M., "The Rise of the Tenor Voice in the Late Eighteenth Century: Mozart’s Opera and Concert Arias" (2014). Doctoral Dissertations. 580. https://opencommons.uconn.edu/dissertations/580 ABSTRACT The Rise of the Tenor Voice in the Late Eighteenth Century: Mozart’s Opera and Concert Arias Joshua Michael May University of Connecticut, 2014 W. A. Mozart’s opera and concert arias for tenor are among the first music written specifically for this voice type as it is understood today, and they form an essential pillar of the pedagogy and repertoire for the modern tenor voice. Yet while the opera arias have received a great deal of attention from scholars of the vocal literature, the concert arias have been comparatively overlooked; they are neglected also in relation to their counterparts for soprano, about which a great deal has been written. There has been some pedagogical discussion of the tenor concert arias in relation to the correction of vocal faults, but otherwise they have received little scrutiny. This is surprising, not least because in most cases Mozart’s concert arias were composed for singers with whom he also worked in the opera house, and Mozart always paid close attention to the particular capabilities of the musicians for whom he wrote: these arias offer us unusually intimate insights into how a first-rank composer explored and shaped the potential of the newly-emerging voice type of the modern tenor voice. -

English Translation of the German by Tom Hammond

Richard Strauss Susan Bullock Sally Burgess John Graham-Hall John Wegner Philharmonia Orchestra Sir Charles Mackerras CHAN 3157(2) (1864 –1949) © Lebrecht Music & Arts Library Photo Music © Lebrecht Richard Strauss Salome Opera in one act Libretto by the composer after Hedwig Lachmann’s German translation of Oscar Wilde’s play of the same name, English translation of the German by Tom Hammond Richard Strauss 3 Herod Antipas, Tetrarch of Judea John Graham-Hall tenor COMPACT DISC ONE Time Page Herodias, his wife Sally Burgess mezzo-soprano Salome, Herod’s stepdaughter Susan Bullock soprano Scene One Jokanaan (John the Baptist) John Wegner baritone 1 ‘How fair the royal Princess Salome looks tonight’ 2:43 [p. 94] Narraboth, Captain of the Guard Andrew Rees tenor Narraboth, Page, First Soldier, Second Soldier Herodias’s page Rebecca de Pont Davies mezzo-soprano 2 ‘After me shall come another’ 2:41 [p. 95] Jokanaan, Second Soldier, First Soldier, Cappadocian, Narraboth, Page First Jew Anton Rich tenor Second Jew Wynne Evans tenor Scene Two Third Jew Colin Judson tenor 3 ‘I will not stay there. I cannot stay there’ 2:09 [p. 96] Fourth Jew Alasdair Elliott tenor Salome, Page, Jokanaan Fifth Jew Jeremy White bass 4 ‘Who spoke then, who was that calling out?’ 3:51 [p. 96] First Nazarene Michael Druiett bass Salome, Second Soldier, Narraboth, Slave, First Soldier, Jokanaan, Page Second Nazarene Robert Parry tenor 5 ‘You will do this for me, Narraboth’ 3:21 [p. 98] First Soldier Graeme Broadbent bass Salome, Narraboth Second Soldier Alan Ewing bass Cappadocian Roger Begley bass Scene Three Slave Gerald Strainer tenor 6 ‘Where is he, he, whose sins are now without number?’ 5:07 [p. -

103 the Music Library of the Warsaw Theatre in The

A. ŻÓRAWSKA-WITKOWSKA, MUSIC LIBRARY OF THE WARSAW..., ARMUD6 47/1-2 (2016) 103-116 103 THE MUSIC LIBRARY OF THE WARSAW THEATRE IN THE YEARS 1788 AND 1797: AN EXPRESSION OF THE MIGRATION OF EUROPEAN REPERTOIRE ALINA ŻÓRAWSKA-WITKOWSKA UDK / UDC: 78.089.62”17”WARSAW University of Warsaw, Institute of Musicology, Izvorni znanstveni rad / Research Paper ul. Krakowskie Przedmieście 32, Primljeno / Received: 31. 8. 2016. 00-325 WARSAW, Poland Prihvaćeno / Accepted: 29. 9. 2016. Abstract In the Polish–Lithuanian Common- number of works is impressive: it included 245 wealth’s fi rst public theatre, operating in War- staged Italian, French, German, and Polish saw during the reign of Stanislaus Augustus operas and a further 61 operas listed in the cata- Poniatowski, numerous stage works were logues, as well as 106 documented ballets and perform ed in the years 1765-1767 and 1774-1794: another 47 catalogued ones. Amongst operas, Italian, French, German, and Polish operas as Italian ones were most popular with 102 docu- well ballets, while public concerts, organised at mented and 20 archived titles (totalling 122 the Warsaw theatre from the mid-1770s, featured works), followed by Polish (including transla- dozens of instrumental works including sym- tions of foreign works) with 58 and 1 titles phonies, overtures, concertos, variations as well respectively; French with 44 and 34 (totalling 78 as vocal-instrumental works - oratorios, opera compositions), and German operas with 41 and arias and ensembles, cantatas, and so forth. The 6 works, respectively. author analyses the manuscript catalogues of those scores (sheet music did not survive) held Keywords: music library, Warsaw, 18th at the Archiwum Główne Akt Dawnych in War- century, Stanislaus Augustus Poniatowski, saw (Pl-Wagad), in the Archive of Prince Joseph musical repertoire, musical theatre, music mi- Poniatowski and Maria Teresa Tyszkiewicz- gration Poniatowska. -

Karel Burian – the Guest of Budapest (1913–1924)

100 Ferenc János Szabó Institute of Musicology, Research Centre for the Humanities Hungarian Academy of Sciences, Budapest Karel Burian – the Guest of Budapest (1913–1924) Abstract | In the present article the last third of Karel Burian’s career is discussed, not only because it is perhaps a less known period of Burian’s biography, but also because it is close- ly connected with Hungarian culture. In these years he appeared in Budapest as a regular guest of the Royal Hungarian Opera mainly as a Wagner singer but also in French, Italian and Hungarian operas, and celebrated his thirty-year jubilee as an opera singer also in Bu- dapest. After a chronological overview, certain special aspects of Burian’s Hungarian activity are examined, e. g. his Hungarian naturalization (the so called ‘Hungarian divorce’) and the political context of his appearances at the end of the First World War. Keywords | Karel Burian – First World War – Hungarian divorce – Hungary – Naturalization – Opera, Scandals – Richard Wagner 1 Introduction1 Even today, the name of the Czech Heldentenor Karel Burian sounds familiar not only in his na- tive land, but also among the opera lovers in Hungary. Despite the fact that it was required to sing in Hungarian on the stage of the Royal Hungarian Opera, the most successful Wagner tenor of the fi rst quarter of the 20th century in Budapest was a foreign singer: Karel Burian. In the present article I discuss the last ten years of his career, not only because it is perhaps a less known period of Burian’s biography, but also because it is closely connected with Hungarian musical culture. -

Der Rosenkavalier by Richard Strauss

Florida State University Libraries Electronic Theses, Treatises and Dissertations The Graduate School 2010 Octavian and the Composer: Principal Male Roles in Opera Composed for the Female Voice by Richard Strauss Melissa Lynn Garvey Follow this and additional works at the FSU Digital Library. For more information, please contact [email protected] THE FLORIDA STATE UNIVERSITY COLLEGE OF MUSIC OCTAVIAN AND THE COMPOSER: PRINCIPAL MALE ROLES IN OPERA COMPOSED FOR THE FEMALE VOICE BY RICHARD STRAUSS By MELISSA LYNN GARVEY A Treatise submitted to the Department of Music in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Music Degree Awarded: Spring Semester, 2010 The members of the committee approve the treatise of Melissa Lynn Garvey defended on April 5, 2010. __________________________________ Douglas Fisher Professor Directing Treatise __________________________________ Seth Beckman University Representative __________________________________ Matthew Lata Committee Member The Graduate School has verified and approved the above-named committee members. ii I’d like to dedicate this treatise to my parents, grandparents, aunt, and siblings, whose unconditional love and support has made me the person I am today. Through every attended recital and performance, and affording me every conceivable opportunity, they have encouraged and motivated me to achieve great things. It is because of them that I have reached this level of educational achievement. Thank you. I am honored to thank my phenomenal husband for always believing in me. You gave me the strength and courage to believe in myself. You are everything I could ever ask for and more. Thank you for helping to make this a reality. -

Historical Vocal Pedagogies

VC565 Historical Vocal Pedagogies Ian Howell [email protected] New England Conservatory of Music 23 September 2013 Monday, September 23, 13 Giulio Caccini b.1551 – d.1618 Florence, Italy Florentine Camerata – Recitative/Text Famous singer, music teacher, composer of Medici court Monday, September 23, 13 Giulio Caccini •Singers vs. instrumentalists •Voce piena, e naturale vs. voce finta •Avoid slides •Decrescendo from attack •Trillo vs. gruppo •Ornamentation for affect of text Monday, September 23, 13 Pier Francesco Tosi b.1647 – d.1742 Soprano Castrato Taught and performed across Europe, especially Vienna, London, and Bologna Monday, September 23, 13 Pier Francesco Tosi •Study solfeggio •voce di testa vs. voce di petto •Head voice soft ≠ shrieking trumpet •scales without separation of [h] or [g] •fast passages on [a], never [i] or [u] •avoid closed versions of [e] and [o] Monday, September 23, 13 Pier Francesco Tosi •Progressive exercises •expression towards a smile •Hold out the length of notes without shrillness and trembling •Messa di voce taught later •Teach on [a], [Ɛ], and [ɔ], not just on [a] •Drag voice high to low, but not low to high Monday, September 23, 13 Pier Francesco Tosi •Appoggiatura is most important grace •Trill is a necessity •No rules for teaching trill Monday, September 23, 13 Pier Francesco Tosi •Study with the mind •Listen to the best •Too much practice and vocal beauty incompatible Monday, September 23, 13 Giambattista Mancini b.1714 – d.1800 Bologna Castrato, studied with Bernacchi (also Senesino’s (Giulio Cesare) -

Western Performing Arts in the Late Ottoman Empire: Accommodation and Formation

2020 © Özgecan Karadağlı, Context 46 (2020): 17–33. Western Performing Arts in the Late Ottoman Empire: Accommodation and Formation Özgecan Karadağlı While books such as Larry Wolff’s The Singing Turk: Ottoman Power and Operatic Emotions on the European Stage offer an understanding of the musicological role of Ottoman-Turks in eighteenth-century European operatic traditions and popular culture,1 the musical influence and significance going the other way is often overlooked, minimised, and misunderstood. In the nineteenth century, Ottoman sultans were establishing theatres in their palaces, cities were hosting theatres and opera houses, and an Ottoman was writing the first Ottoman opera (1874). This article will examine this gap in the history of Western music, including opera, in the Ottoman period, and the slow amalgamation of Western and Ottoman musical elements that arose during the Ottoman Empire. This will enable the reader to gauge the developments that eventually marked the break between the Ottoman era and early twentieth-century modern Turkey. Because even the words ‘Ottoman Empire’ are enough to create a typical orientalist image, it is important to build a cultural context and address critical blind spots. It is an oft- repeated misunderstanding that Western music was introduced into modern-day Turkey after 1 Larry Wolff, The Singing Turk: Ottoman Power and Operatic Emotions on the European Stage (Stanford: Stanford University Press, 2016). 17 18 Context 46 (2020): Karadağlı the proclamation of the Republic in 1923.2 As this article will demonstrate, the intercultural interaction gave rise to institutional support, and as Western music became a popular and accepted genre in the Ottoman Empire of the nineteenth century,3 it influenced political and creative aspirations through the generation of new nationalist music for the Turkish Republic.4 Intercultural Interaction: Pre-Tanzimat and İstibdat Periods, 1828–1908 Although Western music arrived in the Empire in the sixteenth century,5 it took almost two and a half centuries to become established. -

View Program

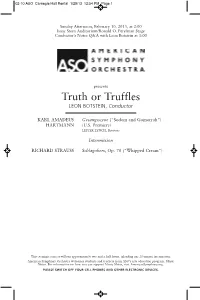

02-10 ASO_Carnegie Hall Rental 1/29/13 12:54 PM Page 1 Sunday Afternoon, February 10, 2013, at 2:00 Isaac Stern Auditorium/Ronald O. Perelman Stage Conductor’s Notes Q&A with Leon Botstein at 1:00 presents Truth or Truffles LEON BOTSTEIN, Conductor KARL AMADEUS Gesangsszene (“Sodom and Gomorrah”) HARTMANN (U.S. Premiere) LESTER LYNCH, Baritone Intermission RICHARD STRAUSS Schlagobers, Op. 70 (“Whipped Cream”) This evening’s concert will run approximately two and a half hours, inlcuding one 20-minute intermission. American Symphony Orchestra welcomes students and teachers from ASO’s arts education program, Music Notes. For information on how you can support Music Notes, visit AmericanSymphony.org. PLEASE SWITCH OFF YOUR CELL PHONES AND OTHER ELECTRONIC DEVICES. 02-10 ASO_Carnegie Hall Rental 1/29/13 12:54 PM Page 2 THE Program KARL AMADEUS HARTMANN Gesangsszene Born August 2, 1905, in Munich Died December 5, 1963, in Munich Composed in 1962–63 Premiered on November 12, 1964, in Frankfurt, by the orchestra of the Hessischer Rundfunk under Dean Dixon with soloist Dietrich Fischer-Dieskau, for whom it was written Performance Time: Approximately 27 minutes Instruments: 3 flutes, 2 piccolos, alto flute, 3 oboes, English horn, 3 clarinets, bass clarinet, 3 bassoons, contrabassoon, 3 French horns, 3 trumpets, piccolo trumpet, 3 trombones, tuba, timpani, percussion (triangle, gong, chimes, cymbals, tamtam, tambourine, tomtoms, timbales, field drum, snare drum, bass drum, glockenspiel, xylophone, vibraphone, marimba), harp, celesta, piano, strings, -

The Hyper Sexual Hysteric: Decadent Aesthetics and the Intertextuality of Transgression in Nick Cave’S Salomé

The Hyper Sexual Hysteric: Decadent Aesthetics and the Intertextuality of Transgression in Nick Cave’s Salomé Gerrard Carter Département d'études du monde anglophone (DEMA) Aix-Marseille Université Schuman - 29 avenue R. Schuman - 13628 Aix-en-Provence, , France e-mail: [email protected] Abstract: Salomé (1988), Nick Cave’s striking interpretation of the story of the Judean princess enhances and extends the aesthetic and textual analysis of Oscar Wilde’s 1891 French symbolist tragedy (Salomé), yet it is largely overlooked. As we examine the prior bricolage in the creation of such a hypertextual work, we initiate a captivating literary discourse between the intertextual practices and influences of biblical and fin-de-siècle literary texts. The Song of Songs, a biblical hypotext inverted by Wilde in the creation of the linguistic-poetic style he used in Salomé, had never previously been fully explored in such an overt manner. Wilde chose this particular book as the catalyst to indulge in the aesthetics of abjection. Subsequently, Cave’s enterprise is entwined in the Song’s mosaic, with even less reserve. Through a semiotic and transtextual analysis of Cave’s play, this paper employs Gérard Genette’s theory of transtextuality as it is delineated in Palimpsests (1982) to chart ways in which Cave’s Salomé is intertwined with not only Wilde but also the Song of Songs. This literary transformation demonstrates the potential and skill of the artist’s audacious postmodern rewriting of Wilde’s text. Keywords: Salomé, Nick Cave, Oscar Wilde, The Song of Songs, Aesthetics, Gérard Genette, Intertextuality, Transtextuality, Transgression, Puvis de Chavannes. -

A Culture of Recording: Christopher Raeburn and the Decca Record Company

A Culture of Recording: Christopher Raeburn and the Decca Record Company Sally Elizabeth Drew A thesis submitted in partial fulfilment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy The University of Sheffield Faculty of Arts and Humanities Department of Music This work was supported by the Arts & Humanities Research Council September 2018 1 2 Abstract This thesis examines the working culture of the Decca Record Company, and how group interaction and individual agency have made an impact on the production of music recordings. Founded in London in 1929, Decca built a global reputation as a pioneer of sound recording with access to the world’s leading musicians. With its roots in manufacturing and experimental wartime engineering, the company developed a peerless classical music catalogue that showcased technological innovation alongside artistic accomplishment. This investigation focuses specifically on the contribution of the recording producer at Decca in creating this legacy, as can be illustrated by the career of Christopher Raeburn, the company’s most prolific producer and specialist in opera and vocal repertoire. It is the first study to examine Raeburn’s archive, and is supported with unpublished memoirs, private papers and recorded interviews with colleagues, collaborators and artists. Using these sources, the thesis considers the history and functions of the staff producer within Decca’s wider operational structure in parallel with the personal aspirations of the individual in exerting control, choice and authority on the process and product of recording. Having been recruited to Decca by John Culshaw in 1957, Raeburn’s fifty-year career spanned seminal moments of the company’s artistic and commercial lifecycle: from assisting in exploiting the dramatic potential of stereo technology in Culshaw’s Ring during the 1960s to his serving as audio producer for the 1990 The Three Tenors Concert international phenomenon. -

A Countertenor's Reference Guide to Operatic Repertoire

A COUNTERTENOR’S REFERENCE GUIDE TO OPERATIC REPERTOIRE Brad Morris A Thesis Submitted to the Graduate College of Bowling Green State University in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of MASTER OF MUSIC May 2019 Committee: Christopher Scholl, Advisor Kevin Bylsma Eftychia Papanikolaou © 2019 Brad Morris All Rights Reserved iii ABSTRACT Christopher Scholl, Advisor There are few resources available for countertenors to find operatic repertoire. The purpose of the thesis is to provide an operatic repertoire guide for countertenors, and teachers with countertenors as students. Arias were selected based on the premise that the original singer was a castrato, the original singer was a countertenor, or the role is commonly performed by countertenors of today. Information about the composer, information about the opera, and the pedagogical significance of each aria is listed within each section. Study sheets are provided after each aria to list additional resources for countertenors and teachers with countertenors as students. It is the goal that any countertenor or male soprano can find usable repertoire in this guide. iv I dedicate this thesis to all of the music educators who encouraged me on my countertenor journey and who pushed me to find my own path in this field. v PREFACE One of the hardships while working on my Master of Music degree was determining the lack of resources available to countertenors. While there are opera repertoire books for sopranos, mezzo-sopranos, tenors, baritones, and basses, none is readily available for countertenors. Although there are online resources, it requires a great deal of research to verify the validity of those sources. -

Symphony Hall, Boston Huntington and Massachusetts Avenues

SYMPHONY HALL, BOSTON HUNTINGTON AND MASSACHUSETTS AVENUES Branch Exchange Telephones, Ticket and Administration Offices, Back Bay 149 1 lostoai Symphony QreSnesfe©J INC SERGE KOUSSEVITZKY, Conductor FORTY-FOURTH SEASON, 1924-1925 PiroErainriime WITH HISTORICAL AND DESCRIPTIVE NOTES BY PHILIP HALE COPYRIGHT, 1925, BY BOSTON SYMPHONY ORCHESTRA, INC. THE OFFICERS AND TPJ 5TEES OF THE BOSTON SYMPHONY ORCHESTRA, Inc. » FREDERICK P. CABOT . Pres.dent GALEN L. STONE ... Vice-President B. ERNEST DANE .... Treasurei FREDERICK P. CABOT ERNEST B. DANE HENRY B. SAWYER M. A. DE WOLFE HOWE GALEN L. STONE JOHN ELLERTON LODGE BENTLEY W, WARREN ARTHUR LYMAN E. SOHlER WELCH W. H. BRENNAN. Manager C E. JUDD Assistant Manager 1429 — THE INST%U<SMENT OF THE IMMORTALS IT IS true that Rachmaninov, Pader- Each embodies all the Steinway ewski, Hofmann—to name but a few principles and ideals. And each waits of a long list of eminent pianists only your touch upon the ivory keys have chosen the Steinway as the one to loose its matchless singing tone, perfect instrument. It is true that in to answer in glorious voice your the homes of literally thousands of quickening commands,, to echo in singers, directors and musicai celebri- lingering beauty or rushing splendor ties, the Steinway is an integral part the genius of the great composers. of the household. And it is equally true that the Steinway, superlatively fine as it is, comet well within the There is a Steinway dealer in your range of the inoderate income and community or near you through "whom meets all the lequirements of the you may purchase a new Steinway modest home.