Copy This! a Historical Perspective on the Use of the Photocopier in Art1

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Embodied Community and Embodied Pedagogy

ZINES, n°2, 2021 MATERIAL MATTERS: EMBODIED COMMUNITY AND EMBODIED PEDAGOGY Kelly MCELROY & Korey JACKSON Oregon State University Libraries and Press [email protected] [email protected] Abstract: In this essay, we outline how materiality can be a tool of critical pedagogy, leading to pleasure, vulnerability, and embodied learning in the classroom. Over the past four years, we have taught an honors colloquium to undergraduate students focused on self-publishing as a means to create social change. As we explore various publishing media, genres, and activist movements with our students, we combine traditional academic activities like scholarly reading and written analysis with informal hands-on craft time. Our students make collages, learn to use the advanced features on a photocopier, and collaborate on hectograph printing among other crafts, all as they begin to put together their own final DIY publication. Students regularly report that the hands-on activities are crucial to their learning, giving them new appreciation for the underground publications they read, through embodied experiences that can’t be replicated with a reading or a quiz. It also builds our community of learners, as we share ideas, borrow glue sticks, and chit-chat as we put our zines together. We will outline how we built and teach this course, placing it within our critical pedagogy – informed by bell hooks, Kevin Kumashiro, and Paulo Freire, among others – and how teaching this course has helped us incorporate embodiment into our other teaching. Keywords: embodied pedagogy, teaching, publishing. 58 Material Matters: Embodied Community and Embodies Pedagogy ZINES, n°2, 2021 INTRODUCTION Alison Piepmeier has argued that, “Zines’ materiality creates College, this course is one of a suite of course offerings community because it creates pleasure, affection, allegiance, and that highlight exploratory discovery and deep dives vulnerability” (2008, 230). -

Glossary of Flexographic Printing Terms

GLOSSARY OF FLEXOGRAPHIC PRINTING TERMS AA: Authors Alterations, changes other than corrections, made by a client after the proofing process has begun. AA's are usually charged to a client as billable time. Abrasion: Process of wearing away the surface of a material by friction. Abrasion marks: Marks on a photographic print or film appearing as streaks or scratches, caused by the condition of the developer. Can be partially removed by swabbing with alcohol. Abrasion resistance: Ability to withstand the effects of repeated rubbing and scuffing. Also called scuff or rub resistance. Abrasion test: A test designed to determine the ability to withstand the effects of rubbing and scuffing. Abrasiveness: That property of a substance that causes it to wear or scratch other surfaces. Absorption: In paper, the property which causes it to take up liquids or vapors in contact with it. In optics, the partial suppression of light through a transparent or translucent material. Acceptance sampling or inspection: The evaluation of a definite lot of material or product that is already in existence to determine its acceptability within quality standards. Accelerate: In flexographic printing, as by the addition of a faster drying solvent or by increasing the temperature or volume of hot air applied to the printed surface. Electrical - To speed rewind shafts during flying splices, and in taking up web slackness. Accordion Fold: Bindery term, two or more parallel folds which open like an accordion. Acetone: A very active solvent used in packaging gravure inks; the fastest drying solvent in the ketone family. Activator: A chemistry used on exposed photographic paper or film emulsion to develop the image. -

Dick Maggiore: What We Can Learn from Xerox

Dick Maggiore: What we can learn from Xerox Tuesday Posted at 7:42 AM Company failed (and failed again) when it strayed from its established core position. By Dick MaggioreSpecial to The Canton Repository The basic positioning principle applies regardless of the size of your business or whether you sell to consumers or other businesses. It also does not matter whether your business sells locally, regionally or nationally, or whether you are for-profit or nonprofit. Your business works best when your brand stands for one idea. That's just the way the minds of your prospects and customers work. Xerox is a remarkable example of a company that did just about everything right in terms of technology, but made many mistakes in go-to-market matters. On the plus side, Xerox built one of the most powerful brands in the world. It achieved this by standing for one idea. Its name became the synonym for the act of making a photocopy, as well as the photocopy itself — the verb and the noun. Not too many brands can claim generic ownership of the category itself. In my industry, one of our favorite pastimes has been watching our friends at Xerox. Their follies demonstrated valuable lessons for business. In 1959, Xerox introduced the Xerox 914, the first automatic copier. Research showed people were not willing to pay 5 cents per copy, but Xerox launched the 914 anyway. The rest is photocopier history. If Xerox had heeded its research, it would have missed a tremendous opportunity to build the world’s greatest photocopier brand and gain notoriety as "the most successful product ever marketed in America" as Forbes magazine declared. -

Factsheet Photocopiers & Laser Printers

7 Photocopier and sept 200 laser printer hazards The LondonCentre Hazards Factsheet Photocopiers and laser printers fatigue, drowsiness, throat and eye minimised. Contact with the tongue, are safe when used occasionally irritation), xylene (can cause menstrual e.g. by touching copied papers with a disorder and kidney failure) and benzene wetted finger can lead to small growths and serviced regularly. But if (carcinogenic and teratogenic). on the tongue. Other health effects they are badly sited, poorly may be irritated eyes, headache and maintained and used frequently Selenium and cadmium sulphide itching skin. Maintenance workers are or for long runs, there are risks Some copiers use a drum impregnated at risk from repeated exposure which to health, ranging from irritated with selenium or cadmium sulphide. can lead to skin and eye sensitisation. The gas emitted from these materials eyes, nose and throat to especially when hot can cause throat Airborne toner dust dermatitis, headaches, premature irritation and sensitisation (i.e. adverse A recent study by the Queensland ageing and reproductive reaction to very tiny quantities of University of Technology in Australia has and cancer hazards. Proper chemical) to exposed workers. Short raised concerns about very small particles ventilation and maintenance are term exposure to high levels of selenium of toner from a number of laser printers by ingestion causes nausea, vomiting, that can become airborne and penetrate essential in eliminating hazards. skin rashes and rhinitis. The UK WEL deep into the lung. It showed that almost for selenium compounds is 0.1 mg/m3 a third studied emit potentially dangerous The chemicals (over an 8 hr reference period). -

Polyester Plate Lithography / Pronto Plates

Kevin Haas | www.wsu.edu/~khaas Polyester Plate Lithography / Pronto Plates CREATING YOUR IMAGE DRAWING MATERIALS Ball Point Pen, Sharpie or Permanent Marker, China Marker/ Litho Crayons, Photocopier Toner (Must be heat-set in an oven or on a hot plate at 225º - 250º for 10 minutes.) PHOTOCOPIED AND DIGITAL IMAGES Using Adobe Photoshop and a laser printer you can easily scan and print images onto polyester plates. A 1200dpi laser printer such as an HP 5000, a GCC Elite XL or a Xante printer will work best. However, it is best to make a few adjustments to your print settings to make polyester plates print easily and accu- Set the Format to the printer you are using and the Page Size to rately at the press. match the size of the polyester plates. Orientation (portrait or landscape) should also be set at this time. By default most laser printers will print images over 133 lines per inch. Lines per inch (lpi) is a measurement of how many 2. Set your Printing Options lines of small varying sized halftone dots are used to create the MB > File > Print with Preview… illusion of a continuous tone image. Since printing these plates by hand requires more ink and pressure than offset printing, which is what these plates were intended for, we need to de- crease the lpi to 75. If you did not do this, the ink sitting on top of all the very tiny halftone dots would likely run together, or ‘bridge’. To prevent this from happening, lower the lpi to main- tain a balance between the amount of ink that is needed to print and the space around the dots to hold water that repels the ink. -

Research and Development Washington, DC 20460 ABSTRACT

United Slates EPA- 600 R- 95-045 7 Enwronmental Protection ZL6ILI Agency March 1995 i= Research and Developmen t OFFICE EQUIPMENT: DESIGN, INDOOR AIR EMISSIONS, AND POLLUTION PREVENTION OPPORTUNITIES Prepared for Office of Radiation and Indoor Air Prepared by Air and Energy Engineering Research Laboratory Research Triangle Park NC 2771 1 EPA REVIEW NOTICE This report has been reviewed by the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency, and approved for publication. Approval does not signify that the contents necessarily reflect the views and policy of the Agency, nor does mention of trade names or commercial products constitute endorsement or recommendation for use. This document is available to the public through the National Technical Informa- tion Service. Springfield, Virginia 22161. EPA- 600 I R- 95-045 March 1995 Office Equipment: Design, Indoor Air Emissions, and Pollution Prevention Opportunities by: Robert Hetes Mary Moore (Now at Cadmus, Inc.) Coleen Northeim Research Triangle Institute Center for Environmental Analysis Research Triangle Park, NC 27709 EPA Cooperative Agreement CR822025-01 EPA Project Officer: Kelly W. Leovic Air and Energy Engineering Research Laboratory Research Triangle Park, NC 2771 1 Prepared for: U.S. Environmental Protection Agency Ofice of Research and Development Washington, DC 20460 ABSTRACT The objective of this initial report is to summarize available information on office ~ equipment design; indoor air emissions of organics, ozone, and particulates from office ~ equipment; and pollution prevention approaches for reducing these emissions. It should be noted that much of the existing emissions data from office equipment are proprietary and not available in the general literature and are therefore not included in this report. -

The Story of Xerography Page 1 of 13

The Story of Xerography Page 1 of 13 Our Heritage, Our Commitment "10-22-38 ASTORIA" This humble legend marks the time and place of an auspicious event. It is the text of the first xerographic image ever fashioned. It was created in a makeshift laboratory in Queens, NY. by a patent attorney named Chester Carlson, who believed that the world was ready for an easier and less costly way to make copies. Carlson was proved right only after a discouraging ten-year search for a company that would develop his invention into a useful product. It was the Haloid Company, a small photo-paper maker in Rochester, N.Y, which took on the challenge and the promise of xerography and thus became, in a breathtakingly short time, the giant multinational company now known to the world as Xerox Corporation. This report contains several stories about xerography: the man who invented it, the company that made it work, and the products it yielded for the benefit of mankind. These stories chronicle a classic American success story: How men of courage and vision grew a highly profitable business from little more than the seed of an idea. Certainly, Xerox has changed greatly in size and scope since the historic 914 copier was introduced in 1959. But we also believe that the basic personality of Xerox has never changed. We are convinced that the essential attributes that brought the young Xerox such spectacular rewards in office copying are the same attributes we need to assure continued success for the mature Xerox as it develops total office information capability. -

Lithographic Blanket Washes

Cleaner Technologies Substitutes Assessment: Lithographic Blanket Washes September 1997 Developed by the Design for the Environment Program in Cooperation with: The University of Tennessee Center for Clean Products and Clean Technologies, Printing Industries of America, The Environmental Group (formerly, the Environment Conservation Board of the Graphic Communications Industry), and The Graphic Arts Technical Foundation NOTICE 7KLVGRFXPHQWKDVEHHQUHYLHZHGE\WKH86(QYLURQPHQWDO3URWHFWLRQ$JHQF\ (3$ DQGDSSURYHGIRUSXEOLFDWLRQ7KHLQIRUPDWLRQFRQWDLQHGKHUHZDVGHYHORSHGE\WKH(3$ 'HVLJQIRU7KH(QYLURQPHQW 'I( 3URJUDPªV/LWKRJUDSK\3URMHFWLQFROODERUDWLRQZLWKSDUWQHUV IURPWKHSULQWLQJLQGXVWU\DQGWKH8QLYHUVLW\RI7HQQHVVHH0HQWLRQRIWUDGHQDPHVRU FRPPHUFLDOSURGXFWVGRHVQRWLPSO\HQGRUVHPHQWRUUHFRPPHQGDWLRQIRUXVH,QIRUPDWLRQRQ FRVWDQGSURGXFWXVDJHZDVSURYLGHGE\LQGLYLGXDOSURGXFWYHQGRUVDQGZDVQRWLQGHSHQGHQWO\ FRUURERUDWHGE\(3$ 'LVFXVVLRQRIIHGHUDOHQYLURQPHQWDOVWDWXWHVLVLQWHQGHGIRULQIRUPDWLRQSXUSRVHVRQO\ WKLVLVQRWDQRIILFLDOJXLGDQFHGRFXPHQWDQGVKRXOGQRWEHUHOLHGXSRQE\FRPSDQLHVWR GHWHUPLQHDSSOLFDEOHUHJXODWLRQV $GUDIWRIWKH&OHDQHU7HFKQRORJLHV6XEVWLWXWHV$VVHVVPHQW/LWKRJUDSKLF%ODQNHW :DVKHVZDVUHOHDVHGIRUSXEOLFFRPPHQWLQ-XO\$)HGHUDO5HJLVWHU1RWLFHRI$YDLODELOLW\ IRU&RPPHQWZDVSXEOLVKHG$XJXVWHVWDEOLVKLQJDGD\FRPPHQWSHULRG:ULWWHQ FRPPHQWVZHUHUHFHLYHGIURPWKUHHSDUWLHV7KHVHFRPPHQWVZHUHUHYLHZHGDQGLQFRUSRUDWHG DVDSSURSULDWH 7KHIROORZLQJPHPEHUVRIWKH86(3$VWDIIDUHSULPDULO\UHVSRQVLEOHIRUWKH LQIRUPDWLRQFROOHFWHGLQWKLVGRFXPHQW 'I(6WDII 6WHSKDQLH%HUJPDQ-HG0HOLQH'DYLG)XKV (3$:RUNJURXS 5REHUW%RHWKOLQJ 6XVDQ.UXHJHU -

Examination of Photocopies and Computer Print Outs

Examination of photocopies and computer print outs Surbhi Mathur Assistant Professor Gujarat Forensic Sciences University What is a photocopy???? • It is a copy of usually written or printed material made with a process in which an image is formed by the action of light usually on an electrically charged surface. Contd…. • It is also called xerography, which was derived from two Greek words “xeros” , meaning dry and “graphos” , meaning writing. • Xerography was invented in the late 1930s by an American patent lawyer named Chester Carlson. It is a printing and photocopying technique that works on the basis of electrostatic charges. How does photocopier machine works??? • To produce photocopies of an original document, the photocopy machine first makes a temporary image, a sort of negative of the original. • Inside the machine is cylinder or drum made of a highly conductive metal, usually aluminum, coated with a photoconductive, often selenium. Contd…. • The surface of the drum is then charged using LED or laser light source. • The printed area of the original document will form positive charge on the drum, forming a latent image of the printed matter. Contd…. • The charge on the image area is used to attract the negative toner particles to make the image visible on the drum surface. • A stronger electrical charge of the same type is given to the paper. This causes toner to transfer from drum to paper. Contd…. • The toner is adhered or fixed to the paper by heat and pressure. • A lamp or hot roller melts the toner, which is absorbed into the paper. Handling of photocopied documents • Photocopied exhibits should be stored in paper folders not plastic. -

Laser Printer - Wikipedia, the Free Encyclopedia

Laser printer - Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia http://en. rvi kipedia.org/r,vi ki/Laser_pri nter Laser printer From Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia A laser printer is a common type of computer printer that rapidly produces high quality text and graphics on plain paper. As with digital photocopiers and multifunction printers (MFPs), Iaser printers employ a xerographic printing process but differ from analog photocopiers in that the image is produced by the direct scanning of a laser beam across the printer's photoreceptor. Overview A laser beam projects an image of the page to be printed onto an electrically charged rotating drum coated with selenium. Photoconductivity removes charge from the areas exposed to light. Dry ink (toner) particles are then electrostatically picked up by the drum's charged areas. The drum then prints the image onto paper by direct contact and heat, which fuses the ink to the paper. HP I-aserJet 4200 series printer Laser printers have many significant advantages over other types of printers. Unlike impact printers, laser printer speed can vary widely, and depends on many factors, including the graphic intensity of the job being processed. The fastest models can print over 200 monochrome pages per minute (12,000 pages per hour). The fastest color laser printers can print over 100 pages per minute (6000 pages per hour). Very high-speed laser printers are used for mass mailings of personalized documents, such as credit card or utility bills, and are competing with lithography in some commercial applications. The cost of this technology depends on a combination of factors, including the cost of paper, toner, and infrequent HP LaserJet printer drum replacement, as well as the replacement of other 1200 consumables such as the fuser assembly and transfer assembly. -

Printing; *Programed Instruction

DOCUMENT RESUME ED 058 150 24 SP 005 354 AUTHOR Strandberg, Joel E. TITLE Feedback Systems for Use with Paper-Based Instructional Products. INSTITUTION Southwest Regional Educational Lab., Inglewood, Calif. SPONs AGENCY National Center for Educational Research and Development (DHEW/OF), Washington, D.C. REPORT NO .SWRL-TR-10 BUREAU NO BR-6-2865 PUB DATE 14 Feb 69 NOTE 21p. EDRS PRICE MF-$0.65 HC-$3.29 DESCRIPTORS *Autoinstructional Aids; *Feedback; *Paper (Material) ;*Printing; *Programed Instruction ABSTRACT This survey describes 15 systems that provide feedback to students. Feedback is defined as informationtransfer from the instructional material to the studentafter a response is made by the student. The feedback is directed primarily tothe student, but when a permanent record of the response occursthis information is also available to the instructor. Each systemis reviewed with respect to 1) state of development,2) production process, 3)reversibility or irreversibility, 4)cost of production, and 5)legal implications. The systems discussed are 1)mimeograph with water soluble dyes and water pens, 2) spirit duplicationand chemical pens, 3)xerography with an erasable overlay, 4)letterpress with water soluble dyes and pens, 5)letter press using latent images and chemical pens, 6) letterpress with a scrapeableoverlay, 7) letterpress with overprinting which is eliminated by aplastic reader, 8)letterpress or offset using electrically conductive inks and an electrically activated feedback, 9)letterpress or offset with a pressure-sensitive chemicalfeedback, 10) letterpress with latent images and overlay printing, 11) letterpress with erasable overlay, 12) letterpress or offset with magnetically activatedfeedback, 13) letterpress or offset with fluorescent activation offeedback, 14) letterpress or offset using absorbent white ink on white, and15) letterpress with prepunched response forms. -

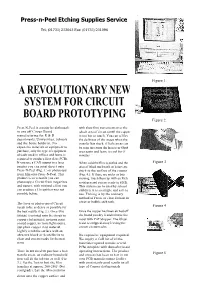

A REVOLUTIONARY NEW SYSTEM for CIRCUIT BOARD PROTOTYPING Figure 2

••• Press-n-Peel Etching Supplies Service Tel; (01733) 233043 Fax: (01733) 231096 Figure 1. A REVOLUTIONARY NEW SYSTEM FOR CIRCUIT BOARD PROTOTYPING Figure 2. Press-N-Peel is a major breakthrough with slow firm movements over the in one off Circuit Board whole area of circuit until the copper manufacturing for R & D is too hot to touch. You can tell by departments, Universities, Schools the darkness of the image when the and the home hobbyist. No transfer has stuck, if light areas can expensive materials or equipment to be seen just run the Iron over that purchase, only the type of equipment area again and leave to cool for 5 already used in offices and home is minutes. required to produce.first class PCBs. If you use a CAD output to a laser When cold the film is peeled and the Figure 3 printer you can print direct onto area of inked trackwork or letters are Press-N-Peel (Fig. 1.) or photocopy stuck to the surface of the copper from film onto Press-N-Peel. This (Fig. 4.). If there are nicks or bits product is so versatile you can missing, touch them up with an Etch photocopy a Circuit from magazines resist pen and you are ready to etch. and papers, with minimal effort you This system can be used by school can produce a Circuit that was not children, it is so simple and safe to possible before. use. Etching is by the ordinary method of Ferric or clear Etchant in The laser or photocopied Circuit a tray or bubble etch tank.