Global Feminisms Comparative Case Studies of Women's

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

NINE DAYS THAT CHANGED the WORLD - Study Guide

-1- NINE DAYS THAT CHANGED THE WORLD - Study Guide Introduction (p. 2) A Message from Newt and Callista Gingrich (p.3) ACTIVITY 1 Story of Pope John Paul II and Nine Days That Changed the World (p. 6) Who was Pope John Paul II (born Karol Wojty_a)? What happened in June 1979 that changed the world? Why is it worth studying? ACTIVITY 2 WHO’S WHO AND WHAT’S WHAT (p. 9) God the Father, Jesus Christ, Holy Spirit, Mary Mother of God, Pope John Paul II, President Ronald Reagan, Lech Walesa, Margaret Thatcher, Anna Walentynowicz, Cardinal Stefan Wyszy_ski, Edward Gierek, General Wojciech Jaruzelski, Leonid Brezhnev, Mikhail Gorbachev, Father Jerzy Popieluszko, Father Franciszek Blachnicki, Saint Stanislaus of Szczepanów, Icon of Black Madonna, Soviet Union, KGB, Cold War, Nine Year Great Novena, Millennium of Polish Christianity ACTIVITY 3 Timeline – 1000+ year history of Christianity in Poland (p. 14) ACTIVITY 4 Fundamental Nature of Man (p. 18) Materialist Vision of Man – Communism Imago Dei – Man is Created in the Image of God – Christianity ACTIVITY 5 Nine Day Pilgrimage to Poland (June 2-10, 1979) (p. 20) ACTIVITY 6 Change after Pilgrimage: Spiritual Renewal and the Rise of Solidarity (p. 23) ACTIVITY 7 Revolutions of 1989 (p. 47) ACTIVITY 8 Victory of the Cross (“Overcoming Evil with Good”) (p. 51) ACTIVITY 9 Memory and Identity (p. 54) ACTIVITY 10 A Future Worthy of Man (p. 58) Lesson Plans for Educators (p. 60) Cast of Nine Days that Changed the World (p. 70) ____________________________________ DRAFT: November 10, 2010 (Updated versions of this Nine Days that Changed the World Study Guide may be downloaded at -2- Introduction On November 9, 1989, the most visible symbol of totalitarian evil, the Berlin Wall, tumbled down. -

The CIA and the Polish Crisis of 1980–1981

DaviesTheCIA and the Polish Crisis of 1980–1981 Review Essay The CIA and the Polish Crisis of 1980–1981 ✣ Douglas J. MacEachin, U.S. Intelligence and the Confrontation in Poland, 1980–81. University Park: Pennsylvania State University Press, 2002. 256 pp. $45.00. Downloaded from http://direct.mit.edu/jcws/article-pdf/6/3/120/696027/1520397041447346.pdf by guest on 29 September 2021 The dramatic events of 1980–1981 in Poland began a process that led over the next decade to the end of the Cold War and the breakup of the Soviet Union. The crucial event in the Communist cession of power in Poland in 1989 was the failure of martial law after it was imposed in December 1981 by General Wojciech Jaruzelski, who was then serving simultaneously as prime minister, defense minister, and ªrst secretary of the Polish United Workers’ Party (PZPR—the Communist party). Douglas MacEachin devotes his book to the events of 1980–1981 as seen from the U.S. Central Intelligence Agency (CIA). He is eminently qualiªed to do so. During the crisis, MacEachin was the senior ofªcial at the CIA who was most familiar with the course of day-to-day developments in Poland and with the intelligence reports of Colo- nel Ryszard J. Kukliñski, a key ofªcer on the Polish General Staff, who kept the United States informed about the Polish government’s efforts to combat the independent trade union, Solidarity.1 The events of 1980–1981 have been extensively reported on, analyzed, and reanalyzed. MacEachin singles out as authoritative three eyewitness ac- counts written in the early to mid-1980s by men on the ground: Nicholas An- drews, Neal Ascherson, and Timothy Garton Ash.2 Andrews was deputy chief of mission at the U.S. -

Polish Journal for American Studies

Rob Kroes Decentering America: Visual Intertextuality and the Quest for a Transnational American Studies PolishPolish Journal Journal for for Polish Journal for American Studies Studies American Journal for Polish Polish Journal for Tadeusz Rachwał Where East Meets West: On Some Locations of America Florian Zappe AmericanAmericanAmerican StudiesStudies Studies The Other Exceptionalism: A Transnational Perspective on Atheism in America YearbookYearbook of theof the Polish Polish Association Association for for American American Studies Studies Anna Pochmara Vol. 12 (Spring 2018) Enslavement to Philanthropy, Freedom from Heredity: Vol. 12 (Spring 2018) Amelia E. Johnson’s and Paul Laurence Dunbar’s Uses and Misuses of Sentimentalism and Naturalism Paulina Ambroży Performance and Theatrical A ect in Steven Millhauser’s Short Story “The Knife-Thrower” Thematic Section | Vol. 12 (Spring 2018) Vol. Transnational American Studies Here and Now Edited by Agnieszka Gra , Ludmiła Janion, Karolina Krasuska Warsaw 2018 www.paas.org.pl Polish Journal for American Studies Yearbook of the Polish Association for American Studies Vol. 12 (Spring 2018) Warsaw 2018 MANAGING EDITOR Marek Paryż EDITORIAL BOARD Izabella Kimak, Mirosław Miernik, Jacek Partyka, Paweł Stachura ADVISORY BOARD Andrzej Dakowski, Jerzy Durczak, Joanna Durczak, Andrew S. Gross, Andrea O’Reilly Herrera, Jerzy Kutnik, John R. Leo, Zbigniew Lewicki, Eliud Martínez, Elżbieta Oleksy, Agata Preis-Smith, Tadeusz Rachwał, Agnieszka Salska, Tadeusz Sławek, Marek Wilczyński REVIEWERS Tomasz Basiuk, Aneta Dybska, Paweł Frelik, Paweł Jędrzejko, Agnieszka Kotwasińska, Anna Krawczyk-Łaskarzewska, Zuzanna Ładyga, Jadwiga Maszewska, Urszula Niewiadomska-Flis, Tadeusz Pióro, Małgorzata Rutkowska, Piotr Skurowski, Justyna Wierzchowska TYPESETTING AND COVER DESIGN Miłosz Mierzyński COVER IMAGE Jerzy Durczak, “Colors for Sale” from the series “Santa Fe.” By permission. -

Of Post-Communism" Michael D. Kennedy

"The End to Soviet-type Society and the Future of Post-Communism" Michael D. Kennedy CSST Working CRSO Working Paper #67 Paper #458 October 1991 THE END TO SOVIET-TYPE SOCIETIES AND THE FUTURE OF POST-COMMUNISM~ Michael D. Kennedy Soviet-type societies are gone. The system that'bnald Reagan called "the evil empire" exists no more. 'The first big step toward their dissolution came in 1980-81, when the Solidarity movement in Poland built the first civil society in a system where communists ruled the state. Civil society had been understood as that set of public social relations with legally constituted autonomy from the state, but Poland's civil society was made in spite of state law and the wishes of the authorities. This Polish civil society was forced underground when martial law was introduced in December of 1981, but it survived over the decade to return to negotiate the end to communist political monopoly in 1989. Solidarity's return to the public sphere was, however, preceded and in-fact enabled by another major step toward the end of Soviet-type society. -In 1987, after nearly two years of trying to modify the Soviet system, Mikhail Gorbachev initiated radical reforms with revolutionary consequences. His policies of perestroika and glasnost' throughout the USSR and the societies it dominated in Eastern Europe moved both authorities and opposition to contemplate changes more fundamental than anyone before even dared imagine. In 1988 and 1989, party and state authorities and leading members of the opposition in Hungary and Poland negotiated a gradual transition away from communist rule. -

Domestic Politics Comes First—Euro Adoption Stretegies in Central Europe

Domestic Politics Comes First—Euro Adoption Stretegies in Central Europe: The Cases of the Czech Republic, Hungary and Poland By Assem Dandashly License, Lebanese University, 2000 M.A., Lebanese American University, 2004 A Dissertation Submitted in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY in the Department of Political Science © Assem Dandashly, 2012 University of Victoria All rights reserved. This dissertation may not be reproduced in whole or in part, by photocopying or other means, without the permission of the author. Domestic Politics Comes First—Euro Adoption Stretegies in Central Europe: The Cases of the Czech Republic, Hungary and Poland By Assem Dandashly License, Lebanese University, 2000 M.A., Lebanese American University, 2004 Supervisory Committee Professor Amy C. Verdun, Supervisor (Department of Political Science) Professor Colin J. Bennett, Departmental Member (Department of Political Science) Professor Oliver Schmidtke, Departmental Member (Department of Political Science) Professor Emmanuel Brunet-Jailly, Outside Member (School of Public Administration) Professor Mitchell P. Smith, Additional Member (University of Oklahoma, Department of Political Science) ii Supervisory Committee Professor Amy C. Verdun, Supervisor (Department of Political Science) Professor Colin J. Bennett, Departmental Member (Department of Political Science) Professor Oliver Schmidtke, Departmental Member (Department of Political Science) Professor Emmanuel Brunet-Jailly, Outside Member (School of Public Administration) -

Übergang Zur Marktwirtschaft Am Ende Des 20. Jahrhunderts

Südosteuropa - Studien ∙ Band 54 (eBook - Digi20-Retro) Iván Berend (Hrsg.) Übergang zur Marktwirtschaft am Ende des 20. Jahrhunderts Verlag Otto Sagner München ∙ Berlin ∙ Washington D.C. Digitalisiert im Rahmen der Kooperation mit dem DFG-Projekt „Digi20“ der Bayerischen Staatsbibliothek, München. OCR-Bearbeitung und Erstellung des eBooks durch den Verlag Otto Sagner: http://verlag.kubon-sagner.de © bei Verlag Otto Sagner. Eine Verwertung oder Weitergabe der Texte und Abbildungen, insbesondere durch Vervielfältigung, ist ohne vorherige schriftliche Genehmigung des Verlages unzulässig. «Verlag Otto Sagner» ist ein Imprint der Kubon & Sagner GmbH. iván Berend - 978-3-95479-732-5 Downloaded from PubFactory at 01/11/2019 09:43:34AM via free access SÜD OSTEUROPA-STUDIEN herausgegeben im Auftrag der Südosteuropa-Gesellschaft von Walter Althammer iván Berend - 978-3-95479-732-5 Downloaded from PubFactory at 01/11/2019 09:43:34AM via free access 00063447 Transition to a Market Economy at the End of the 20th Century • # Übergang zur Marktwirtschaft am Ende des 20. Jahrhunderts Eleventh International Economic History Congress Session A-3, September 12-17, 1994, Milano Edited by Ivan T. Berend Südosteuropa-Gesellschaft iván Berend - 978-3-95479-732-5 Downloaded from PubFactory at 01/11/2019 09:43:34AM via free access Bayerische Staatsbibliothek München Die Deutsche Bibliothek - CIP-Einheitsaufnahme Transition to a market economy at the end of the 20th century Übergang zur Marktwirtschaft am Ende des 20. Jahrhunderts / Eleventh International Economic History Congress, session A-3, September 12-17, 1994, Milan, Italy. Ed. by Ivan T. Berend. Südosteuropa-Gesellschaft, München. - München : Südosteuropa-Ges., 1994 (Südosteuropa-Studien ; Bd. 54) ISBN 3-925450-44-0 NE: Berend, Ivan T. -

The Martial Law Was Inevitable on December 1981 in Poland?

Revista de Științe Politice. Revue des Sciences Politiques • No. 68 • 2020: 99 - 107 ORIGINAL PAPER The Martial Law Was Inevitable on December 1981 in Poland? Tudor Urea1) Abstract: On 1980-1981 the Polish United Workers' Party (Polska Zjednoczona Partia Robotnicza, PZPR) endured a significant crisis. It could not cope to the increase popularity of “Solidarity” movement, the first independent trade union in a Soviet Bloc countries, which quickly becomes a social movement, a symbol of hope and an embodiment of the struggle against communism and Soviet domination which demands the reforms from the government. Solidarity Movement will cause serious damage to the image and the power of the Polish United Workers' Party (Polska Zjednoczona Partia Robotnicza, PZPR). The Polish United Workers' Party (Polska Zjednoczona Partia Robotnicza, PZPR) was undermined even inside by the appearance of the horizontal structures, the comrades who joined the Solidarity Movement though they did not leave the party. The Party was divided by internal fights. Poland’s economy had fall. The Soviet Union interests were deeply affected and it threat with armed intervention. In the leadership of the government and in the leadership of the Polish United Workers' Party (Polska Zjednoczona Partia Robotnicza, PZPR) are placed in key positions people in uniform prepared to act within Poland and who are loyal to the Soviet Union. The Soviet Union chose to act through these men to regaining the control on Poland and the rehabilitation of Polish United Workers' Party (Polska Zjednoczona Partia Robotnicza, PZPR). On December 13, 1981, the Martial Law introduced by General Wojciech Jaruzelski stopped the opposition in order to gain more authority in Poland. -

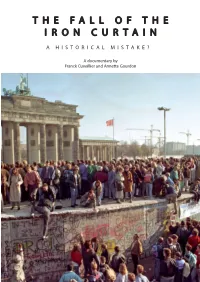

Page 1 1 T H E F a L L O F T H E I R O N C U R T a I N

THE FALL OF THE IRON CURTAIN A HISTORICAL MISTAKE? A documentary by Franck Cuveillier and Annette Gourdon 1 PRODUCER’S NOTE ovember 2019 will mark the 30th She is fluent in Russian and in German. anniversary of the fall of the Berlin For this project, they decided to focus on Wall and of the collapse of communist N four countries, all of which suffered from regimes throughout Eastern Europe. Yet, the Iron Curtain and underwent popular new migration phenomenons today bring uprisings that were quelled by Russia: East Europe to question its borders once again. Germany, Hungary, Czechoslovakia and For 37 years (1952-1989), millions of Poland. Most of the shooting will take place European citizens lived behind an actual in these countries, especially along the line of Iron Curtain, made of over 5,000 miles the former Iron Curtain. Additionally, several of walls and fences preventing them from interviews will be led in Paris and in Moscow. crossing to the West without their country’s formal authorization. It seems interesting As we only have so much time to see this to us to shed light on this specific period in production through, we have decided to European history, at a time when European approach two TV channels, in Poland and nations are reconsidering the 1985 Schengen in Belgium, which already own archives Agreement signed by Western Europe. from that time: TVP and RTBF, respectively. A team from the latter, for example, filmed The goal of this film is to tell the story of the East Germany, Poland and Russia in 1987, Iron Curtain that sliced Europe in half, with aboard a train traveling from Brussels to distance and perspective. -

Quarterly, Volume XXV Research Journal 27

Quarterly, Volume XXV (October-December) Research Journal 27 (4/2020) Volume Editor Grzegorz Rosłan HSS Journal indexed, among others, on the basis of the reference of the Minister of Science and Higher Education in The Central European Journal of Social Sciences and Humanities (CEJSH), ERIH PLUS, DOAJ and Index Copernicus Journal Master List 2019. Issued with the consent of the Rector Editor in Chief Publishing House of Rzeszow University of Technology Lesław GNIEWEK EDITORIAL BOARD Editor-in-Chief Grzegorz OSTASZ Deputy of Editor-in-Chief Justyna STECKO Editorial assistant El żbieta KURZ ĘPA Associate Editors Eugeniusz MOCZUK, Tadeusz OLEJARZ, Marta POMYKAŁA Grzegorz ROSŁAN, Beata ZATWARNICKA-MADURA, Dominik ZIMON Scientific Board Alla ARISTOVA (Ukraine), Heinrich BADURA (Austria), Guido BALDI (Germany) Aleksander BOBKO (Poland), Zbigniew BOCHNIARZ (The USA), Viktor CHEPURKO (Ukraine) Zuzana HAJDUOVÁ (Slovakia), Wilem J.M. HEIJMAN (The Netherlands) Tamara HOVORUN (Ukraine), Paweł GRATA (Poland) Beatriz Urbano LOPEZ DE MENESES (Spain), Aleksandr MEREZHKO (Ukraine) Nellya NYCHKALO (Ukraine), Waldemar PARUCH (Poland), Krzysztof REJMAN (Poland) Annely ROTHKEGEL (Germany), Josef SABLIK (Slovakia), Mykoła STADNIK (Ukraine) Anatoliy TKACH (Ukraine), Michael WARD (Ireland), Natalia ZHYHAYLO (Ukraine) Statistical editor Tomasz PISULA Language editors E-CORRECTOR Magdalena REJMAN-ZIENTEK, Piotr CYREK Volume editor Grzegorz ROSŁAN (Poland) Project of the cover Damian G ĘBAROWSKI The electronic version of the Journal is the final, binding version. e-ISSN 2300-9918 Publisher: Publishing House of Rzeszów University of Technology, 12 Powsta ńców Warszawy Ave., 35-959 Rzeszów (e-mail: [email protected]) http://oficyna.prz.edu.pl Editorial Office: Rzeszów University of Technology, The Faculty of Management, 10 Powsta ńców Warszawy Ave., 35-959 Rzeszów, phone: 17 8651383, e-mail: [email protected] http://hss.prz.edu.pl Additional information and an imprint – p. -

Gender in the EU

Gender in the EU The Future of the Gender Policies In the European Union Heinrich Böll Foundation Regional Office Warsaw ul. Żurawia 45, 00-680 Warsaw, Poland phone: + 48 22 59 42 333, e-mail: [email protected] Gender in the EU_Okladka_CMYK.indd 1 2010-1-29 11:44:11 Gender in the EU The Future of the Gender Policies In the European Union Heinrich Böll Foundation Regional Office Warsaw Warsaw 2009 Gender_in_the_UE_1.indd 1 28.1.2010 17:15:49 The publication was elaborated within the framework of the Regional Program “Gender Democracy/ Women’s Politics”. It contains contributions presented at the regional conference “Gender in the EU. The Future of Gender Policies in the European Union” which took place in Warsaw on 28 October, 2009. Coordinator and editor: Agnieszka Grzybek Proof-reading: Justyna Włodarczyk Graphic design: Studio 27 Published by the Heinrich Böll Foundation Regional Office Warsaw. Printed in Warsaw, 2009. This project has been supported by the European Union: Financing of organizations that are active on the European level for an active European society. The views expressed in this publication are those of the authors alone. They do not necessarily reflect the views of the Heinrich Böll Foundation. ISBN: 978-83-61340-52-2 Copyright by the Heinrich Böll Foundation Regional Office Warsaw. All rights reserved. This publication can be ordered at: Heinrich Böll Foundation Regional Office Warsaw, ul. Żurawia 45, 00-680 Warsaw, Poland phone: + 48 22 59 42 333 e- mail: [email protected] Gender_in_the_UE_1.indd 2 28.1.2010 17:15:49 Contents Introduction Agnieszka Rochon, Agnieszka Grzybek. -

Wesołego Alleluja! Happy Easter! Newsmark Biden Travels to Time-Honored Handiwork Warsaw in Show DZWINEL MARIAN PHOTO: TARGET SHOOTER INCITES INVESTIGATION

POLISH AMERICAN JOURNAL • APRIL 2014 www.polamjournal.com 1 APRIL 2014 • VOL. 103, NO. 4 $2.00 PERIODICAL POSTAGE PAID AT BOSTON, NEW YORK NEW BOSTON, AT PAID PERIODICAL POSTAGE POLISH AMERICAN OFFICES AND ADDITIONAL ENTRY ESTABLISHED.1911 www.polamjournal.com CULTURE-IN-ExILE LEGEND JOURNAL NINA POLAN PASSES DEDICATED TO THE PROMOTION AND CONTINUANCE OF POLISH AMERICAN CULTURE PAGE.27 Wesołego Alleluja! Happy Easter! NEwSMARK Biden Travels to Time-Honored Handiwork Warsaw in Show PHOTO: MARIAN DZWINEL TARGET SHOOTER INCITES INVESTIGATION. There of Support was foul play in Sochi, says Polish biathlete Krystyna Pal- ka, who says her brand new rifl e had been “tampered with.” Russian Aggression in The Polish team had been on track for a medal and Palka did indeed win the fi rst leg of the biathlon relay. Palka’s Ukraine Puts West on Alert shooting had always been her strongest suit, but she missed WARSAW (Polskie Ra- all fi ve targets plus two out of three of the penalty targets, dio) — U.S. vice-president shutting off all hope of a medal win for the Polish team. Joe Biden has said that fur- Palka remains adamant in saying that someone tam- ther sanctions will be im- pered with her rifl e sights. posed by the United States The Polish biathlete represented Poland at the 2006 and and European Union after 2010 Winter Olympics and won the silver medal at the President Putin signs a treaty 2013 World championships. to bring Crimea into the Rus- The Polish Biathlon Association is proceeding with an sian Federation. -

When Reality Fails: Science Fiction and the Fall Of

Kociatkiewicz, Jerzy and Monika Kostera (2002) “When reality fails: Science fiction and the fall of communism in Poland.” In: Mihaela Kelemen and Monika Kostera (eds.) Managing the Transition: Critical Management Research in Eastern Europe. Palgrave, 217-238. When Reality Fails: Science fiction and the fall of Communism in Poland Jerzy Kociatkiewicz Graduate School for Social Research Institute of Philosophy and Sociology Polish Academy of Sciences [email protected] Monika Kostera Academy of Entrepreneurship and Management And Warsaw University [email protected] When the walls fell When the Martial Law was enforced on December 13th, 1981 in Poland, after the Solidarity rebellion that lasted for almost one and a half year, it felt like all hope was being buried forever. The system, once again, proved that it was invincible. The massive popular movement, which had reached 10 millions of members at its peak, was shattered during the following years; the leaders were, once again, imprisoned, censorship tightened anew, and the people subjected to a new wave of unbearably self-righteous propaganda. Its main rhetorical style was named panswinism by Michal Głowiński (1992): „we are all swine,” no one is honest, Party people are swine, but so are the heroes of the Solidarity rebellion. There is no hope. Communism was here to stay and most people tended to believe that is was permanent; some voiced the belief that it might perhaps end in 100 years. And then, in 1989, the state TV started to show glimpses of a remarkable event: the so-called „round-table talks”. Representatives of the opposition and Party officials 1 met and discussed possible scenarios for the future.