Gnu Coreutils Core GNU Utilities for Version 5.93, 2 November 2005

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

A Postgresql Development Environment

A PostgreSQL development environment Peter Eisentraut [email protected] @petereisentraut The plan tooling building testing developing documenting maintaining Tooling: Git commands Useful commands: git add (-N, -p) git ls-files git am git format-patch git apply git grep (-i, -w, -W) git bisect git log (-S, --grep) git blame -w git merge git branch (--contains, -d, -D, --list, git pull -m, -r) git push (-n, -f, -u) git checkout (file, branch, -b) git rebase git cherry-pick git reset (--hard) git clean (-f, -d, -x, -n) git show git commit (--amend, --reset, -- git status fixup, -a) git stash git diff git tag Tooling: Git configuration [diff] colorMoved = true colorMovedWS = allow-indentation-change [log] date = local [merge] conflictStyle = diff3 [rebase] autosquash = true [stash] showPatch = true [tag] sort = version:refname [versionsort] suffix = "_BETA" suffix = "_RC" Tooling: Git aliases [alias] check-whitespace = \ !git diff-tree --check $(git hash-object -t tree /dev/null) HEAD ${1:-$GIT_PREFIX} find = !git ls-files "*/$1" gtags = !git ls-files | gtags -f - st = status tags = tag -l wdiff = diff --color-words=[[:alnum:]]+ wshow = show --color-words Tooling: Git shell integration zsh vcs_info Tooling: Editor Custom settings for PostgreSQL sources exist. Advanced options: whitespace checking automatic spell checking (flyspell) automatic building (flycheck, flymake) symbol lookup ("tags") Tooling: Shell settings https://superuser.com/questions/521657/zsh-automatically-set-environment-variables-for-a-directory zstyle ':chpwd:profiles:/*/*/devel/postgresql(|/|/*)' profile postgresql chpwd_profile_postgresql() { chpwd_profile_default export EMAIL="[email protected]" alias nano='nano -T4' LESS="$LESS -x4" } Tooling — Summary Your four friends: vcs editor shell terminal Building: How to run configure ./configure -C/--config-cache --prefix=$(cd . -

CS101 Lecture 9

How do you copy/move/rename/remove files? How do you create a directory ? What is redirection and piping? Readings: See CCSO’s Unix pages and 9-2 cp option file1 file2 First Version cp file1 file2 file3 … dirname Second Version This is one version of the cp command. file2 is created and the contents of file1 are copied into file2. If file2 already exits, it This version copies the files file1, file2, file3,… into the directory will be replaced with a new one. dirname. where option is -i Protects you from overwriting an existing file by asking you for a yes or no before it copies a file with an existing name. -r Can be used to copy directories and all their contents into a new directory 9-3 9-4 cs101 jsmith cs101 jsmith pwd data data mp1 pwd mp1 {FILES: mp1_data.m, mp1.m } {FILES: mp1_data.m, mp1.m } Copy the file named mp1_data.m from the cs101/data Copy the file named mp1_data.m from the cs101/data directory into the pwd. directory into the mp1 directory. > cp ~cs101/data/mp1_data.m . > cp ~cs101/data/mp1_data.m mp1 The (.) dot means “here”, that is, your pwd. 9-5 The (.) dot means “here”, that is, your pwd. 9-6 Example: To create a new directory named “temp” and to copy mv option file1 file2 First Version the contents of an existing directory named mp1 into temp, This is one version of the mv command. file1 is renamed file2. where option is -i Protects you from overwriting an existing file by asking you > cp -r mp1 temp for a yes or no before it copies a file with an existing name. -

Lecture 7 Network Management and Debugging

SYSTEM ADMINISTRATION MTAT.08.021 LECTURE 7 NETWORK MANAGEMENT AND DEBUGGING Prepared By: Amnir Hadachi and Artjom Lind University of Tartu, Institute of Computer Science [email protected] / [email protected] 1 LECTURE 7: NETWORK MGT AND DEBUGGING OUTLINE 1.Intro 2.Network Troubleshooting 3.Ping 4.SmokePing 5.Trace route 6.Network statistics 7.Inspection of live interface activity 8.Packet sniffers 9.Network management protocols 10.Network mapper 2 1. INTRO 3 LECTURE 7: NETWORK MGT AND DEBUGGING INTRO QUOTE: Networks has tendency to increase the number of interdependencies among machine; therefore, they tend to magnify problems. • Network management tasks: ✴ Fault detection for networks, gateways, and critical servers ✴ Schemes for notifying an administrator of problems ✴ General network monitoring, to balance load and plan expansion ✴ Documentation and visualization of the network ✴ Administration of network devices from a central site 4 LECTURE 7: NETWORK MGT AND DEBUGGING INTRO Network Size 160 120 80 40 Management Procedures 0 AUTOMATION ILLUSTRATION OF NETWORK GROWTH VS MGT PROCEDURES AUTOMATION 5 LECTURE 7: NETWORK MGT AND DEBUGGING INTRO • Network: • Subnets + Routers / switches Time to consider • Automating mgt tasks: • shell scripting source: http://www.eventhelix.com/RealtimeMantra/Networking/ip_routing.htm#.VvjkA2MQhIY • network mgt station 6 2. NETWORK TROUBLES HOOTING 7 LECTURE 7: NETWORK MGT AND DEBUGGING NETWORK TROUBLESHOOTING • Many tools are available for debugging • Debugging: • Low-level (e.g. TCP/IP layer) • high-level (e.g. DNS, NFS, and HTTP) • This section progress: ping trace route GENERAL ESSENTIAL TROUBLESHOOTING netstat TOOLS STRATEGY nmap tcpdump … 8 LECTURE 7: NETWORK MGT AND DEBUGGING NETWORK TROUBLESHOOTING • Before action, principle to consider: ✴ Make one change at a time ✴ Document the situation as it was before you got involved. -

Unix Command Line; Editors

Unix command line; editors Karl Broman Biostatistics & Medical Informatics, UW–Madison kbroman.org github.com/kbroman @kwbroman Course web: kbroman.org/AdvData My goal in this lecture is to convince you that (a) command-line-based tools are the things to focus on, (b) you need to choose a powerful, universal text editor (you’ll use it a lot), (c) you want to be comfortable and skilled with each. For your work to be reproducible, it needs to be code-based; don’t touch that mouse! Windows vs. Mac OSX vs. Linux Remote vs. Not 2 The Windows operating system is not very programmer-friendly. Mac OSX isn’t either, but under the hood, it’s just unix. Don’t touch the mouse! Open a terminal window and start typing. I do most of my work directly on my desktop or laptop. You might prefer to work remotely on a server, instead. But I can’t stand having any lag in looking at graphics. If you use Windows... Consider Git Bash (or Cygwin) or turn on the Windows subsystem for linux 3 Cygwin is an effort to get Unix command-line tools in Windows. Git Bash combines git (for version control) and bash (the unix shell); it’s simpler to deal with than Cygwin. Linux is now accessible in Windows 10, but you have to enable it. If you use a Mac... Consider Homebrew and iTerm2 Also the XCode command line tools 4 Homebrew is a packaging system; iTerm2 is a Terminal replacement. The XCode command line tools are a must for most unixy things on a Mac. -

Common Commands Cheat Sheet by Mmorykan Via Cheatography.Com/89673/Cs/20411

Common Commands Cheat Sheet by mmorykan via cheatography.com/89673/cs/20411/ Scripting Scripting (cont) GitHub bash filename - Runs script sleep value - Forces the script to wait value git clone <url > - Clones gitkeeper url Shebang - "# !bi n/b ash " - First line of bash seconds git add <fil ena me> - Adds the file to git script. Tells script what binary to use while [[ condition ]]; do stuff; done git commit - Commits all files to git ./file name - Also runs script if [[ condition ]]; do stuff; fi git push - Pushes all git files to host # - Creates a comment until [[ condition ]]; do stuff; done echo ${varia ble} - Prints variable words=" h ouse dogs telephone dog" - Package / Networking hello_int = 1 - Treats "1 " as a string Declares words array dnf upgrade - Updates system packages Use UPPERC ASE for constant variables for word in ${words} - traverses each dnf install - Installs package element in array Use lowerc ase _wi th_ und ers cores for dnf search - Searches for package for counter in {1..10} - Loops 10 times regular variables dnf remove - Removes package for ((;;)) - Is infinite for loop echo $(( ${hello _int} + 1 )) - Treats hello_int systemctl start - Starts systemd service as an integer and prints 2 break - exits loop body systemctl stop - Stops systemd service mktemp - Creates temporary random file for ((count er=1; counter -le 10; counter ++)) systemctl restart - Restarts systemd service test - Denoted by "[[ condition ]]" tests the - Loops 10 times systemctl reload - Reloads systemd service condition -

Unix/Linux Command Reference

Unix/Linux Command Reference .com File Commands System Info ls – directory listing date – show the current date and time ls -al – formatted listing with hidden files cal – show this month's calendar cd dir - change directory to dir uptime – show current uptime cd – change to home w – display who is online pwd – show current directory whoami – who you are logged in as mkdir dir – create a directory dir finger user – display information about user rm file – delete file uname -a – show kernel information rm -r dir – delete directory dir cat /proc/cpuinfo – cpu information rm -f file – force remove file cat /proc/meminfo – memory information rm -rf dir – force remove directory dir * man command – show the manual for command cp file1 file2 – copy file1 to file2 df – show disk usage cp -r dir1 dir2 – copy dir1 to dir2; create dir2 if it du – show directory space usage doesn't exist free – show memory and swap usage mv file1 file2 – rename or move file1 to file2 whereis app – show possible locations of app if file2 is an existing directory, moves file1 into which app – show which app will be run by default directory file2 ln -s file link – create symbolic link link to file Compression touch file – create or update file tar cf file.tar files – create a tar named cat > file – places standard input into file file.tar containing files more file – output the contents of file tar xf file.tar – extract the files from file.tar head file – output the first 10 lines of file tar czf file.tar.gz files – create a tar with tail file – output the last 10 lines -

Georgia Department of Revenue

Form MV-9W (Rev. 6-2015) Web and MV Manual Georgia Department of Revenue - Motor Vehicle Division Request for Manufacture of a Special Veteran License Plate ______________________________________________________________________________________ Purpose of this Form: This form is to be used to apply for a military license plate/tag. This form should not be used to record a change of ownership, change of address, or change of license plate classification. Required documentation: You must provide a legible copy of your service discharge (DD-214, DD-215, or for World War II veterans, a WD form) indicating your branch and term of service. If you are an active duty member, a copy of the approved documentation supporting your current membership in the respective reserve or National Guard unit is required. In the case of a retired reserve member from that unit, you must furnish approved documentation supporting the current retired membership status from that reserve unit. OWNER INFORMATION First Name Middle Initial Last Name Suffix Owners’ Full Legal Name: Mailing Address: City: State: Zip: Telephone Number: Owner(s)’ Full Legal Name: First Name Middle Initial Last Name Suffix If secondary Owner(s) are listed Mailing Address: City: State: Zip: Telephone Number: VEHICLE INFORMATION Passenger Vehicle Motorcycle Private Truck Vehicle Identification Number (VIN): Year: Make: Model: CAMPAIGN/TOUR of DUTY Branch of Service: SERVICE AWARD Branch of Service: LICENSE PLATES ______________________ LICENSE PLATES ______________________ World War I World -

General Education and Liberal Studies Course List

GELS 2020–2021 General Education/Liberal Studies/Minnesota Transfer Curriculum 2020–2021 Course List This course list is current as of March 25, 2021. For the most current information view the Current GELS/MnTC list on the Class Schedule page at www.metrostate.edu. This is the official list of Metropolitan State University courses that meet the General Education and Liberal Studies (GELS) requirements for all undergraduate students admitted to the university. To meet the university’s General Education and Liberal Studies (GELS) requirements, students must complete each of the 10 goal areas of the Minnesota Transfer Curriculum (MnTC) and complete 48 unduplicated credits. Eight (8) of the 48 credits must be upper division (300-level or higher) to fulfill the university’s Liberal Studies requirement. Each course title is followed by a number in parenthesis (4). This number indicates the number of credits for that course. Course titles followed by more than one number, such as (2-4), indicate a variable-credit course. Superscript Number: • Superscript number (10) indicates that a course meets more than one goal area requirement. For example, NSCI 20410 listed under Goal 3 meets Goals 3 and 10. Although the credits count only once, the course satisfies the two goal area requirements. • Separated by a comma (3,LS) indicates that a course will meet both areas indicated. • Separated by a forward slash (7/8) indicates that a course will meet one or the other goal area but not both. Superscript LS (LS): • Indicates that a course will meet the Liberal Studies requirement. Asterisk (*): • Indicates that a course can be used to meet goal area requirements, but cannot be used as General Education or Liberal Studies Electives. -

The Linux Command Line

The Linux Command Line Fifth Internet Edition William Shotts A LinuxCommand.org Book Copyright ©2008-2019, William E. Shotts, Jr. This work is licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution-Noncommercial-No De- rivative Works 3.0 United States License. To view a copy of this license, visit the link above or send a letter to Creative Commons, PO Box 1866, Mountain View, CA 94042. A version of this book is also available in printed form, published by No Starch Press. Copies may be purchased wherever fine books are sold. No Starch Press also offers elec- tronic formats for popular e-readers. They can be reached at: https://www.nostarch.com. Linux® is the registered trademark of Linus Torvalds. All other trademarks belong to their respective owners. This book is part of the LinuxCommand.org project, a site for Linux education and advo- cacy devoted to helping users of legacy operating systems migrate into the future. You may contact the LinuxCommand.org project at http://linuxcommand.org. Release History Version Date Description 19.01A January 28, 2019 Fifth Internet Edition (Corrected TOC) 19.01 January 17, 2019 Fifth Internet Edition. 17.10 October 19, 2017 Fourth Internet Edition. 16.07 July 28, 2016 Third Internet Edition. 13.07 July 6, 2013 Second Internet Edition. 09.12 December 14, 2009 First Internet Edition. Table of Contents Introduction....................................................................................................xvi Why Use the Command Line?......................................................................................xvi -

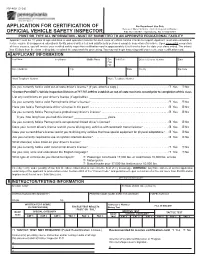

Penndot Form MV-409

MV-409 (3-18) www.dmv.pa.gov APPLICATION FOR CERTIFICATION OF For Department Use Only BureauP.O. Box of Motor 68697 Vehicles Harrisburg, • Vehicle PAInspection 17106-8697 Division OFFICIAL VEHICLE SAFETY INSPECTOR • PRINT OR TYPE ALL INFORMATION - MUST BE SUBMITTED TO AN APPROVED EDUCATIONAL FACILITY Applicant must be 18 years of age and have a valid operator’s license for each class of vehicle he/she intends to inspect. Applicant must also complete a lecture course at an approved educational facility, pass a written test and satisfactorily perform a complete inspection of a vehicle. upon successful completion of these courses, you will receive your certified safety inspection certification card in approximately 6 to 8 weeks from the date your class ended. The school has 35 days from the class ending date to submit the paperwork for processing. You may not begin inspecting until you receive your certification card. A APPLICANT INFORMATION Last Name First Name Middle Name Sex birth Date Driver’s License Number State r M r F Street Address City State County Zip Code Work Telephone Number Home Telephone Number Do you currently hold a valid out-of-state driver’s license? (If yes, attach a copy.) . r Yes r No *Contact PennDOT’s Vehicle Inspection Division at 717-787-2895 to establish an out-of-state mechanic record prior to completion of this class. List any restrictions on your driver’s license (if applicable): ______________________________________________________________ Do you currently hold a valid Pennsylvania driver’s license? . r Yes r No Have you held a Pennsylvania driver’s license in the past? . -

LINUX INTERNALS LABORATORY III. Understand Process

LINUX INTERNALS LABORATORY VI Semester: IT Course Code Category Hours / Week Credits Maximum Marks L T P C CIA SEE Total AIT105 Core - - 3 2 30 70 100 Contact Classes: Nil Tutorial Classes: Nil Practical Classes: 36 Total Classes: 36 OBJECTIVES: The course should enable the students to: I. Familiar with the Linux command-line environment. II. Understand system administration processes by providing a hands-on experience. III. Understand Process management and inter-process communications techniques. LIST OF EXPERIMENTS Week-1 BASIC COMMANDS I Study and Practice on various commands like man, passwd, tty, script, clear, date, cal, cp, mv, ln, rm, unlink, mkdir, rmdir, du, df, mount, umount, find, unmask, ulimit, ps, who, w. Week-2 BASIC COMMANDS II Study and Practice on various commands like cat, tail, head , sort, nl, uniq, grep, egrep,fgrep, cut, paste, join, tee, pg, comm, cmp, diff, tr, awk, tar, cpio. Week-3 SHELL PROGRAMMING I a) Write a Shell Program to print all .txt files and .c files. b) Write a Shell program to move a set of files to a specified directory. c) Write a Shell program to display all the users who are currently logged in after a specified time. d) Write a Shell Program to wish the user based on the login time. Week-4 SHELL PROGRAMMING II a) Write a Shell program to pass a message to a group of members, individual member and all. b) Write a Shell program to count the number of words in a file. c) Write a Shell program to calculate the factorial of a given number. -

Unix (And Linux)

AWK....................................................................................................................................4 BC .....................................................................................................................................11 CHGRP .............................................................................................................................16 CHMOD.............................................................................................................................19 CHOWN ............................................................................................................................26 CP .....................................................................................................................................29 CRON................................................................................................................................34 CSH...................................................................................................................................36 CUT...................................................................................................................................71 DATE ................................................................................................................................75 DF .....................................................................................................................................79 DIFF ..................................................................................................................................84