A Political Tsunami Hits Amazon Conservation

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Linking REDD+ to Support Brazil's Climate Goals and Implementation

FOREST TRENDS PUBLIC-PRIVATE FINANCE INITIATIVE NOVEMBER 2016 Linking REDD+ to Support Brazil’s Climate Goals and Implementation of the Forest Code Rupert Edwards SUPPORTERS About Forest Trends Forest Trends works to conserve forests and other ecosystems through the creation and wide adoption of a broad range of environmental finance, markets and other payment and incentive mechanisms. Forest Trends does so by: 1) providing transparent information on ecosystem values, finance, and markets through knowledge acquisition, analysis, and dissemination; 2) convening diverse coalitions, partners, and communities of practice to promote environmental values and advance development of new markets and payment mechanisms; and 3) demonstrating successful tools, standards, and models of innovative finance for conservation. About Forest Trends’ Public-Private Finance Initiative Conserving forest and ecosystems and transforming land use at scale to sustainable low-emissions production systems requires substantial investment. Our Public-Private Finance Initiative is strategically focused on creating architectures that increase the amount of capital flowing to land use practices which reduce emissions from deforestation and degradation, improve the productivity of agricultural and livestock systems, and enhance live- lihoods of rural populations. Linking REDD+ to Support Brazil’s Climate Goals and Implementation of the Forest Code Rupert Edwards November 2016 SUPPORTERS Acknowledgments We gratefully acknowledge Ruben Lubowski (Environmental Defense Fund), Ronaldo Seroa da Motta (Earth Innovation Institute and State University of Rio de Janeiro), and Josh Gregory (Forest Trends) for their anal- ysis and review for this paper. We would also like to thank David Tepper, Director of Forest Trends’ Public-Private Finance Initiative, and Michael Jenkins, President and CEO of Forest Trends, for their guidance. -

World Wildlife Fund

WWF 9 WORLD WILDLIFE FUND SEMI-ANNUAL TECHNICAL PROGRESS REPORT USAID Grant #512-G-OO-96-00041 Protected Areas & Sustainable Resource Management Amazon Development Policy Capacity Building October 1, 2001 to March 31, 2002 Component I- Protected Areas Jau National Park Highlights • Three new species recorded for Jaii -A Ph.D. research study conducted by FVA staff member Sergio Borges registered three species ofbirds new to the Jaii National Park: SeiuntS novaboracensis, Miyopagisflaviventris, and Nonnula amaurocephala. The latter is a species very rarely recorded in the Amazon. The bird inventory of Jaii National Park is now one of the best known in the entire Brazilian Amazon, as it is the only one in existence that has been maintained systematically over an uninterrupted ten-year period. • FVA receives Environmental Award - Ms. Muriel Saragoussi, representing FVA activities in the Jaii National Park, was one offive recipients ofthe Claudia Magazine Award for her contributions to nature conservation. Claudia Magazine is the most important weekly publication in Brazil dedicated to women. The award targets women who have made significant contributions in the areas ofhealth, education, social entrepreneurship, and the environment. Progress Windows on Biodiversity Project - With the conclusion ofits third phase last semester, the project entered its fourth and final phase, and will focus on the monitoring and evaluation ofthe results attained, as well as on the publication ofmaterials for dissemination. In this last phase, the project will continue to carry out the field expedition program. In February, FVA implemented an internal planning process where decisions were reached on the 2002 work plan and on coordination ofthe thematic areas ofthe project. -

WILDLIFE TRAFFICKING in BRAZIL Sandra Charity and Juliana Machado Ferreira

July 2020 WILDLIFE TRAFFICKING IN BRAZIL Sandra Charity and Juliana Machado Ferreira TRAFFIC: Wildlife Trade in Brazil WILDLIFE TRAFFICKING IN BRAZIL TRAFFIC, the wildlife trade monitoring network, is a leading non-governmental organisation working globally on trade in wild animals and plants in the context of both biodiversity conservation and sustainable development. © Jaime Rojo / WWF-US Reproduction of material appearing in this report requires written permission from the publisher. The designations of geographical entities in this publication, and the presentation of the material, do not imply the expression of any opinion whatsoever on the part of TRAFFIC or its supporting organisations concerning the legal status of any country, territory, or area, or of its authorities, or concerning the delimitation of its frontiers or boundaries. TRAFFIC David Attenborough Building, Pembroke Street, Cambridge CB2 3QZ, UK. Tel: +44 (0)1223 277427 Email: [email protected] Suggested citation: Charity, S., Ferreira, J.M. (2020). Wildlife Trafficking in Brazil. TRAFFIC International, Cambridge, United Kingdom. © WWF-Brazil / Zig Koch © TRAFFIC 2020. Copyright of material published in this report is vested in TRAFFIC. ISBN: 978-1-911646-23-5 UK Registered Charity No. 1076722 Design by: Hallie Sacks Cover photo: © Staffan Widstrand / WWF This report was made possible with support from the American people delivered through the U.S. Agency for International Development (USAID). The contents are the responsibility of the authors and do not necessarily -

Sustainable Bioproducts in Brazil: Disputes and Agreements on a Common Ground Agenda for Agriculture and Nature Protection

On the Map Sustainable bioproducts in Brazil: disputes and agreements on a common ground agenda for agriculture and nature protection Gerd Sparovek, University of São Paulo, Piracicaba, Brazil Laura Barcellos Antoniazzi, Agroicone, São Paulo, Brazil Alberto Barretto, Brazilian Bioethanol Science and Technology Laboratory, Campinas, Brazil Ana Cristina Barros, Ministry of Environment of Brazil, Brasília, Brazil Maria Benevides, ANDI Comunicação e Direitos, Brasília, Brazil Göran Berndes, Chalmers University of Technology, Gothenburg, Sweden Estevão do Prado Braga, Suzano Pulp and Paper, São Paulo, Brazil Miguel Calmon, International Union for Conservation of Nature, Washington D.C., USA Paulo Henrique Groke Jr, Ecofuturo Instituto, São Paulo, Brazil Fábio Nogueira de Avelar Marques, Plantar Carbon, Belo Horizonte, Brazil Mauricio Palma Nogueira, Agroconsult, Florianópolis, Brazil Luis Fernando Guedes Pinto, Imafl ora, Piracicaba, Brazil Vinicius Precioso, Avesso Sustentabilidade, São Paulo, Brazil Received March 3, 2015; revised January 3, 2016; and accepted January 22, 2016 View online at Wiley Online Library (wileyonlinelibrary.com); DOI: 10.1002/bbb.1636; Biofuels, Bioprod. Bioref. (2016) Abstract: A key question for food, biofuels, and bioproducts production is how agriculture affects the environment, and social and economic development. In Brazil, a large agricultural producer and among the biologically wealthiest of nations, this question is challenging and opinions often clash. The Brazilian parliament and several stakeholders have recently debated the revision of the Forest Act, the most important legal framework for conservation of natural vegetation on Brazilian private agricultural lands. Past decades have shown improvements in the agricultural sector with respect to productivity and effi ciency, along with great reductions in deforestation and growth of environmentally certifi ed pro- duction. -

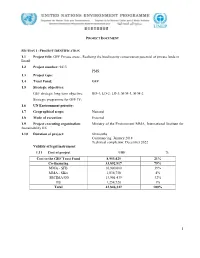

1.1 Project Title: GEF Private Areas

; PROJECT DOCUMENT SECTION 1: PROJECT IDENTIFICATION 1.1 Project title: GEF Private areas - Realising the biodiversity conservation potential of private lands in Brazil 1.2 Project number: 9413 PMS: 1.3 Project type: 1.4 Trust Fund: GEF 1.5 Strategic objectives: GEF strategic long-term objective: BD-4; LD-2; LD-3; SFM-1, SFM-2 Strategic programme for GEF IV: 1.6 UN Environment priority: 1.7 Geographical scope: National 1.8 Mode of execution: External 1.9 Project executing organization: Ministry of the Environment MMA, International Institute for Sustainability IIS 1.10 Duration of project: 60 months Commencing: January 2018 Technical completion: December 2022 Validity of legal instrument: 1.11 Cost of project US$ % Cost to the GEF Trust Fund 8,953,425 21% Co-financing 33,892,917 79% MMA - SFB 16,900,000 39% MMA - SBio 1,836,758 4% SECIMA/GO 13,901,439 32% IIS 1,254,720 3% Total 42,846,342 100% 1 1.12 Project summary In 2010, the Convention on Biological Diversity established 20 Aichi Biodiversity Targets, whose achievement depend on actions that go beyond the establishment of protected areas governed by government, multi-party bodies, or indigenous people. Brazil, one of the most biodiverse countries worldwide, has two pillars for biodiversity conservation: one of the largest systems of protected areas in the world (governed by federal government or by multi-party bodies) and the protected indigenous reserves. However, Brazil does not have a comprehensive set of instruments that support effective programs of biodiversity conservation in private areas, where approximately 53% of its remnant vegetation cover are located. -

Land Reform and Biodiversity Conservation in Brazil in the 1990S: Conflict and the Articulation of Mutual Interests

Land Reform and Biodiversity Conservation in Brazil in the 1990s: Conflict and the Articulation of Mutual Interests LAURY CULLEN JR.,∗ KEITH ALGER,† AND DENISE M. RAMBALDI‡ ∗IPE-ˆ Instituto de Pesquisas Ecol´ogicas, C.P. 31, Teodoro Sampaio, SP, Brasil, CEP 19.280-000, S˜ao Paulo, Brasil, email [email protected] †Center for Applied Biodiversity Science, Conservation International, 1919 M Street NW, Suite 600, Washington, D.C. 20036, U.S.A. and Universidade Estadual de Santa Cruz, Ilh´eus, Bahia, Brasil ‡Associa¸c˜ao Mico-Le˜ao-Dourado, Rodovia BR 101, Km 214, Caixa Postal 109.968, Casimiro de Abreu 28860-970, Rio de Janeiro, Brasil Abstract: Land-reform and environmental movements, revitalized by the democratization of civil society in Brazil in the 1990s, found their objectives in conflict over forested parcels that settlers want for conversion to agriculture but that are important for wildlife conservation. In the Atlantic Forest, where 95% of the forest is gone, we reviewed three cases of Brazilian nongovernmental organization (NGOs) engagement with the land- reform movement with respect to forest remnants neighboring protected areas that have insufficient habitat for the long-term survival of unique endangered species. In the Pontal do Paranapanema (Sao˜ Paulo), Poc¸o das Antas (Rio de Janeiro), and southern Bahia, environmental NGOs have supported agricultural alternatives that improve livelihood options and provide incentives for habitat conservation planning. Where land-reform groups were better organized, technical cooperation on settlement agriculture permitted the exploration of mutual interests in conciliating the productive landscape with conservation objectives. Processes of regular consultation among NGOs, environmental agencies, and the private sector revealed that there was less zero- sum conflict over the same lands than commonly perceived. -

High Prevalence and Low Intensity of Infection by Batrachochytrium Dendrobatidis in Rainforest Bullfrog Populations in Southern Brazil

Herpetological Conservation and Biology 15(1):118–130. Submitted: 3 September 2019; Acceptance: 24 January 2020; Published 30 April 2020. HIGH PREVALENCE AND LOW INTENSITY OF INFECTION BY BATRACHOCHYTRIUM DENDROBATIDIS IN RAINFOREST BULLFROG POPULATIONS IN SOUTHERN BRAZIL ROSELI COELHO DOS SANTOS1,8,9, VELUMA IALÚ MOLINARI DE BASTIANI2, DANIEL MEDINA3, LUISA PONTES RIBEIRO3,4, MARIANA RETUCI PONTES3,4, DOMINGOS DA SILVA LEITE5, LUÍS FELIPE TOLEDO3, GILZA MARIA DE SOUZA FRANCO6, AND ELAINE MARIA LUCAS1,7 1Programa de Pós-Graduação em Ciências Ambientais, Universidade Comunitária da Região de Chapecó, 89809-000 Chapecó, Santa Catarina, Brazil 2Laboratório de Ecologia e Química, Universidade Comunitária da Região de Chapecó, 89809-000 Chapecó, Santa Catarina, Brazil 3Laboratório de História Natural de Anfíbios Brasileiros (LaHNAB), Departamento de Biologia Animal, Instituto de Biologia, Universidade Estadual de Campinas, 13083-862 Campinas, São Paulo, Brazil 4Programa de Pós-Graduação em Ecologia, Universidade Estadual de Campinas, 13083-862 Campinas, São Paulo, Brazil 5Laboratório de Micologia Molecular, Departamento de Genética, Evolução, Microbiologia e Imunologia, Universidade Estadual de Campinas, 13083-862 Campinas, São Paulo, Brazil 6Universidade Federal da Fronteira Sul, Campus Realeza, 85770-000 Realeza, Paraná, Brazil 7Departamento de Zootecnia e Ciências Biológicas, Universidade Federal de Santa Maria, Campus de Palmeira das Missões, 98300-000 Palmeira das Missões, Rio Grande do Sul, Brazil 8Programa de Pós-Graduação em Biologia, Universidade do Vale do Rio dos Sinos, Campus São Leopoldo, 93022-750 São Leopoldo, Rio Grande do Sul, Brazil 9Corresponding author, e-mail: [email protected] Abstract.—American Bullfrogs (Lithobates catesbeianus) are considered important reservoirs and vectors of the fungus Batrachochytrium dendrobatidis (Bd), which can cause the disease chytridiomycosis in many amphibian species. -

Strategies for Managing Biodiversity in Amazonian Fisheries

Strategies for Managing Biodiversity in Amazonian Fisheries Mauro Luis Ruffino Flood Plain Natural Resources Management Project - ProVárzea The Brazilian Environmental and Renewable Natural Resources Institute- IBAMA Rua Ministro João Gonçalves de Souza, s/nº - 69.075-830 Manaus, AM - Brazil. Email: [email protected] 1 Table of Contents Abstract..............................................................................................................................................................................................................3 Introduction......................................................................................................................................................................................................3 The fishery resource and its exploitation.............................................................................................................................5 Summary of target species status and resource trends................................................................................................6 Importance of biodiversity in the fishery............................................................................................................................8 Management history - successes and failures....................................................................................................................10 How biodiversity has been incorporated in fisheries management......................................................................16 Results and -

Brazil: National Biodiversity Mainstreaming and Institutional

BRAZIL National Biodiversity Mainstreaming and Institutional Consolidation Project and Sustainable Cerrado Initiative Report No. 154858 DECEMBER 18, 2020 © 2021 International Bank for Reconstruction and Development / The World Bank 1818 H Street NW Washington DC 20433 Telephone: 202-473-1000 Internet: www.worldbank.org Attribution—Please cite the work as follows: World Bank. 2021. Brazil—National Biodiversity Mainstreaming and Institutional Consolidation Project and Sustainable Cerrado Initiative. Independent Evaluation Group, Project Performance Assessment Report 154858. Washington, DC: World Bank. This work is a product of the staff of The World Bank with external contributions. The findings, interpretations, and conclusions expressed in this work do not necessarily reflect the views of The World Bank, its Board of Executive Directors, or the governments they represent. The World Bank does not guarantee the accuracy of the data included in this work. The boundaries, colors, denominations, and other information shown on any map in this work do not imply any judgment on the part of The World Bank concerning the legal status of any territory or the endorsement or acceptance of such boundaries. RIGHTS AND PERMISSIONS The material in this work is subject to copyright. Because The World Bank encourages dissemination of its knowledge, this work may be reproduced, in whole or in part, for noncommercial purposes as long as full attribution to this work is given. Any queries on rights and licenses, including subsidiary rights, should be addressed -

Economic Valuation of the Ecosystem Services Provided by a Protected Area in the Brazilian Cerrado: Application of the Contingent Valuation Method F

http://dx.doi.org/10.1590/1519-6984.21215 Original Article Economic valuation of the ecosystem services provided by a protected area in the Brazilian Cerrado: application of the contingent valuation method F. M. Resendea,b*, G. W. Fernandesa,c, D. C. Andraded and H. D. Néderd aLaboratório de Ecologia Evolutiva & Biodiversidade, Departamento de Biologia Geral, Universidade Federal de Minas Gerais – UFMG, Avenida Presidente Antônio Carlos, 6627, Pampulha, CP 486, CEP 30161-970, Belo Horizonte, MG, Brazil bLaboratório de Biogeografia da Conservação, Departamento de Ecologia, Instituto de Ciências Biológicas – ICB, Universidade Federal de Goiás – UFG, Avenida Esperança, s/n, Câmpus Samambaia, CP 131, CEP 74001-970, Goiânia, GO, Brazil cDepartment of Biology, Stanford University, Stanford CA 94305, USA dInstituto de Economia, Universidade Federal de Uberlândia – UFU, Avenida João Naves de Ávila, 2121, Campus Santa Mônica, CEP 38408-100, Uberlândia, MG, Brazil *e-mail: [email protected] Received: December 17, 2015 – Accepted: May 31, 2016 – Distributed: November 31, 2017 Abstract Considering that the economic valuation of ecosystem services is a useful approach to support the conservation of natural areas, we aimed to estimate the monetary value of the benefits provided by a protected area in southeast Brazil, the Serra do Cipó National Park. We calculated the visitor’s willingness to pay to conserve the ecosystems of the protected area using the contingent valuation method. Located in a region under intense anthropogenic pressure, the Serra do Cipó National Park is mostly composed of rupestrian grassland ecosystems, in addition to other Cerrado physiognomies. We conducted a survey consisting of 514 interviews with visitors of the region and found that the mean willingness to pay was R$ 7.16 year–1, which corresponds to a total of approximately R$ 716,000.00 year–1. -

Ecology and Conservation of the Jaguar (Panthera Onca) in the Cerrado Grasslands of Central Brazil

Ecology and conservation of the jaguar (Panthera onca ) in the Cerrado grasslands of central Brazil Dissertation zur Erlangung des akademischen Grades des Doktors der Naturwissenschaften (Dr. rer. nat.) Eingereicht im Fachbereich Biologie, Chemie, Pharmazie der Freien Universität Berlin vorgelegt von Rahel Sollmann aus Essen Berlin, November 2010 Diese Dissertation wurde am Leibniz-Institut für Zoo- und Wildtierforschung Berlin im Zeitraum April 2007 bis November 2010 angefertigt und am Institut für Biologie der Freien Universität Berlin eingereicht. 1. Gutachter: Prof. Dr. Heribert Hofer 2. Gutachter: Prof. Dr. Silke Kipper Disputation am: 19. Januar 2011 This dissertation is based on the following manuscripts: 1. Rahel Sollmann a,b , Mariana Malzoni Furtado a,c , Beth Gardner d, Heribert Hofer b, Anah T. A. Jácomo a, Natália Mundim Tôrres a,e , Leandro Silveira a (in press, Biological Conservation; http://www.elsevier.com/wps/find/journaldescription.cws_home/ 405853/description#description ; DOI: 10.1016/j.biocon.2010.12.011). Improving density estimates for elusive carnivores: accounting for sex-specific detection and movements using spatial capture-recapture models for jaguars in central Brazil. 2. Rahel Sollmann a,b , Julie Betsch f, Mariana Malzoni Furtado a,c , José Antonio Godoy g, Heribert Hofer b, Anah T. A. Jácomo a, Francisco Palomares g, Severine Roques g, Natália Mundim Tôrres a,e , Carly Vynne h, Leandro Silveira a. Prey selection and optimal foraging of a large predator: feeding ecology of the jaguar in central Brazil. 3. Rahel Sollmann a,b , Mariana Malzoni Furtado a,c , Heribert Hofer b, Anah T. A. Jácomo a, Natália Mundim Tôrres a,e , Leandro Silveira a. -

Brazilian Coastal and Marine Protected Areas Importance, Current Status and Recommendations

Brazilian Coastal and Marine Protected Areas Importance, Current Status and Recommendations Carina Tostes Abreu United Nations – Nippon Foundation of Japan Fellowship Programme DIVISION FOR OCEAN AFFAIRS AND THE LAW OF THE SEA OFFICE OF LEGAL AFFAIRS THE UNITED NATIONS NEW YORK December 2015 DISCLAIMER The views expressed herein are those of the author and do not necessarily re- flect the views of the Government of Brazil, the United Nations, the Nippon Foundation of Japan, or University of Rhode Island. © 2015 Carina T. Abreu. All rights reserved. ii ABSTRACT Brazil's maritime region holds an extraordinary biodiversity with more than 7,400 km of coastline and 3.6 million km² of exclusive economic zone. This area includes 3,000 km of coral reefs and 12% of the world's mangroves. These areas and their natural resources are extremely important for the economy of the country. Around 18 % of Brazilian population lives on the coast and economic activities in this areas account for about 70% of the country’s GDP, resulting in pressures on coastal resources and negative impacts on the biodiversity. The main Brazilian strategy for biodiversity conservation in situ is the establishment and the maintenance of the National System of Protected Areas. Despite efforts to create Protected Areas, the Marine Biome has the smallest percentage of area under protection in Brazil, with about 1.5%. Moreover, the few designated marine protected areas have not been well implemented and managed. Historically, public and political ignores economic benefits of ecosystem services and non-utilitarian benefits, instead considering only the immediate values obtained from direct exploration.