Conservation and Coastal Element Data Inventory and Analysis

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

USGS 7.5-Minute Image Map for Crawl Key, Florida

U.S. DEPARTMENT OF THE INTERIOR CRAWL KEY QUADRANGLE U.S. GEOLOGICAL SURVEY FLORIDA-MONROE CO. 7.5-MINUTE SERIES 81°00' 57'30" 55' 80°52'30" 5 000m 5 5 5 5 5 5 5 5 5 5 5 24°45' 01 E 02 03 04 05 06 07 08 09 10 690 000 FEET 11 12 24°45' Grassy Key 27 000m 37 N 5 27 BANANA BLVD 37 Florida Crawl Key Bay Long Point Key 35 150 000 FEET «¬5 T65S R33E ¤£1 Little Crawl Key Valhalla 5 34 MARATHON 2736 Fat Deer 2736 Fat Deer Key Key Deer Key T66S R33ER M D LU CO P C3O 2735 2735 O C E O R N O ATLANTIC M OCEAN East 2734 Turtle Shoal 2734 2733 2733 Imagery................................................NAIP, January 2010 Roads..............................................©2006-2010 Tele Atlas Names...............................................................GNIS, 2010 42'30" 42'30" Hydrography.................National Hydrography Dataset, 2010 Contours............................National Elevation Dataset, 2010 Hawk Channel 2732 2732 West Turtle Shoal FLORIDA Coffins Patch 2731 2731 2730 2730 2729 2729 CO E ATLANTIC RO ON OCEAN M 40' 40' 2727 2727 2726 2726 2725 2725 110 000 FEET 2724 2724000mN 24°37'30" 24°37'30" 501 660 000 FEET 502 5 5 5 5 507 5 5 5 511 512000mE 81°00' 03 04 57'30" 05 06 08 55' 09 10 80°52'30" ^ Produced by the United States Geological Survey SCALE 1:24 000 ROAD CLASSIFICATION 7 North American Datum of 1983 (NAD83) 3 FLORIDA Expressway Local Connector 3 World Geodetic System of 1984 (WGS84). -

Resolution 2015-139

Sponsored by: Puto CITY OF MARATHON, FLORIDA RESOLUTION 2015-139 A RESOLUTION OF THE CITY COUNCIL OF THE CITY OF MARATHON' FLORIDA, ADOPTING THE 2015 UPDATE oF THE LOCAL MITIGATION STRATEGY AS REQUIRE,D BY STATE AND FEDERAL REGULATIONS TO QUALIFY FOR CERTAIN MITIGATION GRANT F.UNDING; PROVIDING FOR AN EFFECTIVE DATE. WHEREAS, the City of Marathon Council adopted a Local Mitigation Strategy (LMS) update in2005, and an update in2011; and WHEREAS, Monroe County and the cities of Key West, Key Colony Beach, Layton, Islamorada, and Marathon have experienced hurricanes and other natural hazañ,events that pose risks to public health and safety and which may cause serious property damage; and WHEREAS, the Robert T. Stafford Disaster Relief and Emergency Management Act, as amended by the Disaster Mitigation Act of 2000, requires local jurisdictions to adopt mitigation plans in order to be eligible for post-disaster and pre-clisaster grants to implement Ãrtain mitigation projects; and WHEREAS, pursuant to Florida Administrative Code Section2TP-22, the County and municipalities must have a formal LMS Working Group ancl the I-MS Working Group must review and update the LMS every five years in order to maintain eligibility for mitigation grant programs; and WHEREAS, the National Flood Insurance Reform Act of 1994, the Flood Insurance Reform Act of 2004, as amended, require local jurisdictions to aclopt a mitigation to be eligible for grants to implement certain flood mitigation projects; and WHEREAS, the planning process required by the State of Florida -

Central Keys Area Reasonable Assurance Documentation

Central Keys Area Reasonable Assurance Documentation F K R A D FKRAD Program December 2008 Prepared for FLORIDA DEPARTMENT OF ENVIRONMENTAL PROTECTION Watershed Management Bureau Tallahassee, Florida Prepared by Camp, Dresser & McKee, Inc. URS Corporation Southern 1715 N. Westshore Boulevard 7650 Courtney Campbell Causeway Tampa, Florida 33607 Tampa, Florida 33607 Florida Department of Environmental Protection REASONABLE ASSURANCE DOCUMENTATION CENTRAL KEYS AREA F K R A D December 2008 ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS The Central Keys Area Reasonable Assurance Document was developed under the direction of Mr. Fred Calder and Mr. Pat Fricano of the Florida Department of Environmental Protection (FDEP) with the assistance of the following stakeholder’s representatives: Ms. Suzy Thomas, Director of Community Services and Mr. Mike Hatfield, P.E., Weiler Engineering, City of Marathon Mr. Clyde Burnett, Mayor/City Administrator, City of Key Colony Beach; Mr. Philip “Skip” Haring, Assistant to Mayor City of Layton; Ms. Elizabeth Wood, P.E., Wastewater Section Chief, Monroe County; Mr. Jaime Barrera, FDOT District VI; and Mr. Fred Hand, Bureau of Facilities, FDEP. The authors gratefully acknowledge the comments review comments of the Stakeholders technical representatives and Mr. Gus Rios, Manager of FDEP’s Marathon Service Office. The document was developed a collaborative effort led by Mr. Scott McClelland of CDM Inc. and Mr. Stephen Lienhart of URS Corporation. S:\FDEP\Central RAD\FKRAD Central Cover and Prelim.doc i Florida Department of Environmental Protection REASONABLE ASSURANCE DOCUMENTATION CENTRAL KEYS AREA F K R A D December 2008 Central Keys Area Stakeholders Documents As a measure of reasonable assurance and support of this document, the stakeholders in the Central Keys Area (City of Marathon, City of Key Colony Beach, City of Layton, Monroe County, FDOT and the Florida State Parks Service) have provided signed documents confirming that the management activities identified in this document indeed reflect the commitments of the stakeholders. -

Collier Miami-Dade Palm Beach Hendry Broward Glades St

Florida Fish and Wildlife Conservation Commission F L O R ID A 'S T U R N P IK E er iv R ee m Lakewood Park m !( si is O K L D INDRIO ROAD INDRIO RD D H I N COUNTY BCHS Y X I L A I E O W L H H O W G Y R I D H UCIE BLVD ST L / S FT PRCE ILT SRA N [h G Fort Pierce Inlet E 4 F N [h I 8 F AVE "Q" [h [h A K A V R PELICAN YACHT CLUB D E . FORT PIERCE CITY MARINA [h NGE AVE . OKEECHOBEE RA D O KISSIMMEE RIVER PUA NE 224 ST / CR 68 D R !( A D Fort Pierce E RD. OS O H PIC R V R T I L A N N A M T E W S H N T A E 3 O 9 K C A R-6 A 8 O / 1 N K 0 N C 6 W C W R 6 - HICKORY HAMMOCK WMA - K O R S 1 R L S 6 R N A E 0 E Lake T B P U Y H D A K D R is R /NW 160TH E si 68 ST. O m R H C A me MIDWAY RD. e D Ri Jernigans Pond Palm Lake FMA ver HUTCHINSON ISL . O VE S A t C . T I IA EASY S N E N L I u D A N.E. 120 ST G c I N R i A I e D South N U R V R S R iv I 9 I V 8 FLOR e V ESTA DR r E ST. -

In the United States Court of Appeals for the Eleventh

Case: 15-11771 Date Filed: 03/28/2016 Page: 1 of 25 [PUBLISH] IN THE UNITED STATES COURT OF APPEALS FOR THE ELEVENTH CIRCUIT ________________________ No. 15-11771 ________________________ D.C. Docket No. 4:12-cv-10072-JEM F.E.B. CORP., a Florida corporation, Plaintiff - Appellant, versus UNITED STATES OF AMERICA, Defendant - Appellee. ________________________ Appeal from the United States District Court for the Southern District of Florida ________________________ (March 28, 2016) Before WILSON, JULIE CARNES, and EBEL,* Circuit Judges. EBEL, Circuit Judge: __________________ * Honorable David M. Ebel, United States Circuit Judge for the Tenth Circuit, sitting by designation. Case: 15-11771 Date Filed: 03/28/2016 Page: 2 of 25 Plaintiff-Appellant F.E.B. Corp. (“F.E.B.”) brought this action against Defendant-Appellee United States (“the government”) seeking to quiet title to a spoil island just off Key West, Florida. Because we find that the Quiet Title Act’s statute of limitations has run, see 28 U.S.C. § 2409a(g), we AFFIRM the district court’s dismissal of the action for lack of subject matter jurisdiction. I. BACKGROUND The island in question, known as Wisteria Island (or “the island”), is situated in the Gulf of Mexico, less than a mile off the coast of Key West, Florida. It is not a natural island, but rather was formed as a result of dredging operations performed under the auspices of the United States Navy (“Navy”) in nearby Key West Harbor during the first half of the nineteenth century. As Navy contractors deepened the channels in the harbor to improve shipping and aviation access, they deposited the dredged material on a nearby plot of submerged land. -

Currently the Bureau of Beaches and Coastal Systems

CRITICALLY ERODED BEACHES IN FLORIDA Updated, June 2009 BUREAU OF BEACHES AND COASTAL SYSTEMS DIVISION OF WATER RESOURCE MANAGEMENT DEPARTMENT OF ENVIRONMENTAL PROTECTION STATE OF FLORIDA Foreword This report provides an inventory of Florida's erosion problem areas fronting on the Atlantic Ocean, Straits of Florida, Gulf of Mexico, and the roughly seventy coastal barrier tidal inlets. The erosion problem areas are classified as either critical or noncritical and county maps and tables are provided to depict the areas designated critically and noncritically eroded. This report is periodically updated to include additions and deletions. A county index is provided on page 13, which includes the date of the last revision. All information is provided for planning purposes only and the user is cautioned to obtain the most recent erosion areas listing available. This report is also available on the following web site: http://www.dep.state.fl.us/beaches/uublications/tech-rut.htm APPROVED BY Michael R. Barnett, P.E., Bureau Chief Bureau of Beaches and Coastal Systems June, 2009 Introduction In 1986, pursuant to Sections 161.101 and 161.161, Florida Statutes, the Department of Natural Resources, Division of Beaches and Shores (now the Department of Environmental Protection, Bureau of Beaches and Coastal Systems) was charged with the responsibility to identify those beaches of the state which are critically eroding and to develop and maintain a comprehensive long-term management plan for their restoration. In 1989, a first list of erosion areas was developed based upon an abbreviated definition of critical erosion. That list included 217.6 miles of critical erosion and another 114.8 miles of noncritical erosion statewide. -

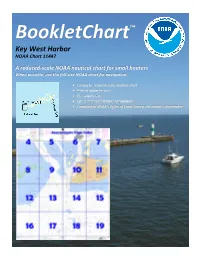

Bookletchart™ Key West Harbor NOAA Chart 11447

BookletChart™ Key West Harbor NOAA Chart 11447 A reduced-scale NOAA nautical chart for small boaters When possible, use the full-size NOAA chart for navigation. Published by the frequently call here, and the harbor is a safe haven for any vessel. Prominent features.–Easy to identify when standing along the keys are National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration 300-foot-high radio towers about 0.3 mile eastward of Fort Taylor, the National Ocean Service hotel 0.3 mile south of Key West Bight, the cupola close south of the Office of Coast Survey hotel, and a 110-foot-high abandoned lighthouse, 0.5 mile east- northeastward of Fort Taylor. Numerous tanks, lookout towers, and www.NauticalCharts.NOAA.gov masts are prominent, but difficult to identify. Also conspicuous is a 888-990-NOAA white radar dome and an aerobeacon on Boca Chica Key, and the white dome of the National Weather Service station and the aerobeacon at What are Nautical Charts? Key West International Airport. From southward, several apartment complexes, condominiums, and hotels on the south shore extending Nautical charts are a fundamental tool of marine navigation. They show from just west of Key West International Airport to the abandoned water depths, obstructions, buoys, other aids to navigation, and much lighthouse are prominent. more. The information is shown in a way that promotes safe and Channels.–Main Ship Channel is the only deep-draft approach to Key efficient navigation. Chart carriage is mandatory on the commercial West. Federal project depth is 34 feet from the Straits of Florida to a ships that carry America’s commerce. -

Florida Forever Work Plan

Florida Forever Work Plan January 1, 2003 prepared by South Florida Water Management District Florida Forever Work Plan Contributors South Florida Water Management District Florida Forever Work Plan January 1, 2003 Contributors Christine Carlson Dolores Cwalino Fred Davis Jude Denick Juan Diaz-Carreras Andy Edwards Paul Ellis William Helfferich Sally Kennedy Phil Kochan Tom McCracken Kim O’Dell Steve Reel Bonnie Rose Dawn Rose Wanda Caffie-Simpson Andrea Stringer iii Florida Forever Work Plan Contributors iv Florida Forever Work Plan Executive Summary EXECUTIVE SUMMARY In 1999, the Florida Forever program was created, which authorized the issuance of bonds in an amount not to exceed $3 billion for acquisitions of land and water areas. This revenue is to be used for the purposes of restoration, conservation, recreation, water resource development, historical preservation and capital improvements to the acquired land and water. The program is intended to accomplish environmental restoration, enhance public access and recreational enjoyment, promote long-term management goals and facilitate water resource development. The water management districts create a five-year plan that identifies projects meeting specific criteria for the Florida Forever program. Each district integrates its surface water improvement and management plans, Save Our Rivers (SOR) land acquisition lists, stormwater management projects, proposed water resource development and water body restoration projects and other activities that support the goals of Florida Forever. Thirty-five percent of the Florida Forever bond proceeds are distributed annually to the Florida Department of Environmental Protection (FDEP) for land acquisition and capital expenditures in order to implement the priority lists submitted by the water management districts. -

Florida Keys Interesting Interlopers

NIGHT WATCH RENT BATTLE The Studios of Key West’s board seeks Traps set to capture giant Gambian pouch reprieve on rent hike for The Armory, negoti- rats on Grassy Key have been catching some ating with the Historic Florida Keys interesting interlopers. See story, 3A. Foundation. See story, 2A. WWW.KEYSNET.COM WEDNESDAY,APRIL 18 , 2012 VOLUME 59, NO. 31 ● 25 CENTS ISLAMORADA Council open to sewer district By DAVID GOODHUE told council members that his Governor approves $50M for Keys process regarding wastewater. Makepeace said he would [email protected] colleagues came to the con- But Councilmen Don make a report on the benefits clusion that forming an inde- wastewater projects. See story, 6A Achenberg, Dave Purdo and of creating a wastewater dis- Most of the five members pendent district would be the Vice Mayor Ken Philipson trict at the May 10 Village of the Islamorada Village best way to address the vil- plants. Blackburn said creat- attention, Blackburn said. said they are willing to con- Council meeting. Council said they are willing lage’s wastewater needs. ing the district will give “There’s no way we can sider the proposal. to consider forming an inde- Councilman Ted Blackburn Islamorada more of a seat at discuss wastewater and what- “I am in the middle, but I Legal settlement pendent wastewater treatment agreed. Islamorada will be the table with Key Largo ever else is going on in the would like to discuss it fur- The Village Council last district similar to Key Largo’s. sending its wastewater to the going forward. -

March 2019 Monthly Bacteriological Reports

FKAA BACTERIA MONTHLY REPORT PWSID# 4134357 Month: March 2019 H.R.S. LAB # E56717 & E55757 MMO‐MUG/ Cl2 pH RETEST MMO‐MUG/ 100ML DATE 100ML Cl2 pH SERVICE AREA # 1 S.I. LAB Date Sampled: 3/4/2019 101 Hyatt Windward Point‐3675 S. Roosevelt Blvd A 3.1 9.21 103 Conch Train Maintenance‐1802 Staples Ave. A 2.1 9.17 105 Casa Marina Resort ‐ 1500 Reynolds Ave A 3.0 9.18 107 Community Pool‐300 Catherine St. A 3.4 9.20 109 FKAA Key West Pumping Station‐301 Southard St. A 3.4 9.18 111 Hyatt Resort‐601 Front St. A 3.3 9.21 113 Strunk Lumberyard‐1111 Eaton St. (rear) A 3.0 9.10 115 Casa Gato Apts.‐1209 Virginia St. A 3.0 9.20 117 Circle K/Shell‐1890 N. Roosevelt Blvd. A 3.1 9.21 119 Pizza Hut‐3023 N. Roosevelt Blvd. A 3.1 9.18 153 Convalescent Center‐1400 Kennedy Dr A 3.0 9.18 123 Hertz/Welcome Center‐3840 N. Roosevelt Blvd. A 3.0 9.15 125 Las Salinas Condo‐3930 S. Roosevelt Blvd. A 3.2 9.21 127 Advanced Discount Auto Parts‐1835 Flagler Ave. A 2.7 9.20 129 807 Washington St. (#101) A 3.0 9.18 131 Dewey House‐504 South St. A 3.3 9.22 133 Harbor Place Condo‐107 Front St. A 3.2 9.25 135 Old Town Trolley Barn‐126 Simonton St. A 3.2 9.19 137 U.S. Navy Peary Court Housing‐White/Southard St. -

Bac Rpt-January 2021.Xlsx

FKAA BACTERIA MONTHLY REPORT Month: January 2021 PWSID# 4134357 H.R.S. LAB # E56717 & E55757 MMO‐MUG/ Cl2 pH RETEST MMO‐MUG/ 100ML DATE 100ML Cl2 pH SERVICE AREA # 1 S.I. LAB Date Sampled: 1/6/2021 101 Hyatt Windward Point‐3675 S. Roosevelt Blvd A 3.0 9.10 102 Sheraton Suites‐2001 S. Roosevelt Blvd A 2.9 9.05 104 1310 Johnson St A 2.8 9.08 105 Casa Marina Resort ‐ 1500 Reynolds Ave A 2.6 9.03 106 Santa Maria Joint Venture‐1401 Simonton St. A 2.9 9.06 107 Community Pool‐300 Catherine St. A 3.2 9.13 109 FKAA Key West Pumping Station‐301 Southard St. A 3.4 9.16 110 Guy Harvy's‐515 Greene St. A 3.2 9.06 111 Hyatt Resort‐601 Front St. A 2.7 9.06 112 Key West Seaport‐631 Greene St. A 3.0 9.06 113 Strunk Lumberyard‐1111 Eaton St. (rear) A 2.8 9.11 114 US Navy Trumbo Pt. OMI Fleming Key Bridge A 2.7 9.15 115 Casa Gato Apts.‐1209 Virginia St. A 2.6 9.23 116 827 Eisenhower Dr. A 2.9 9.18 117 Circle K/Shell‐1890 N. Roosevelt Blvd. A 2.9 9.22 118 Fairfield Inn‐2400 N. Roosevelt Blvd. A 3.0 9.20 119 Pizza Hut‐3023 N. Roosevelt Blvd. A 3.1 9.21 120 US Navy Housing Elem. School Sigsbee‐Felton Rd. A 2.9 9.20 122 Customer Residence‐3704 Flagler Ave. -

ART in PUBLIC PLACES Request for Proposals (RFP)

ART IN PUBLIC PLACES Request for Proposals (RFP) MONROE COUNTY PUBLIC LIBRARY, MARATHON BRANCH & ADULT EDUCATION CENTER 3490 Overseas Hwy. Marathon, Monroe County, Florida 33050 RFP accessed through Demandstar by calling (800)711-1712 www.demandstar.com or www.monroecounty-fl.gov Board of County Commissioners (BOCC) Mayor Sylvia Murphy, District 5 Mayor Pro Tem Danny Kolhage, District 1 SUBMISSION DEADLINE Michelle Coldiron, District 2 November 14, 2019, by 3:00 p.m. EST Heather Carruthers, District 3 David Rice, District 4 THE ART IN PUBLIC PLACES PROGRAM Monroe County Art in Public Places (AIPP) is a County appointed committee responsible for the commission and purchase of public art by contemporary artists in any media. The Monroe County Art in Public Places Ordinance No. 022-2001 mandates that one percent (1%) of new County building construction costing a minimum of $500,000.00 and renovations costing a minimum of $100,000.00 be set aside to fund this program. A committee comprised of five (5) voting members appointed by the County Commission, plus two (2) non-voting members appointed by the County Administrator, pre-qualifies, reviews and recommends projects to the Board of County Commissioners (BOCC). The Monroe County Art in Public Places program is administered by the Florida Keys Council of the Arts (FKCA). BUDGET The maximum art budget amount, inclusive of all costs for artists, including installation, is Fifty- six Thousand and 00/100 ($56,000.00) Dollars, for any and all commissions for the two (2) interior projects. The $56,000 is allocated as follows: Fifty Thousand and 00/100 ($50,000.00) Dollars for suspended artwork in the atrium, with the remaining Six Thousand and 00/100 ($6,000.00) Dollars to be used for terrazzo floor design.