Deregulation of Air Transport Agreements

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Home Airline Info Links Disclaimer Contact About News Detail

SEARCH HOME AIRLINE INFO LINKS DISCLAIMER CONTACT ABOUT NEWS DETAIL Verfasst am: 27.07.09 00:00 AKTUELLE BRITISH AIRWAYS SPECIALS AB WIEN Von: Martin Metzenbauer Wer bis zum 4. August 2009 einen Langstreckenflug zu einer von 33 Auch MAP wendet sich an Brüssel ausgewählten Destinationen auf www.ba.com bucht, kann vom 1. August bis Der österreichische ACMI- und Charterspezialist befürchtet durch den zum 16. August bzw. vom 17. August 2009 bis Zusammenschluss von AUA und Lufthansa eine deutliche Verschlechterung des zum 31. März 2010 zu... mehr » Geschäftsumfeldes. SKYLINK: SONDERBUDGETS, UM KOSTEN ZU DRÜCKEN Wie das Nachrichtenmagazin "profil" in seiner Ausgabe vom 27.07.2009 berichtet, hat der Vorstand der Flughafen Wien AG ab 2007 begonnen, Teile der Skylink-Investitionen in geheime Sonderbudgets auszulagern, um so die offiziellen Baukosten zu... mehr » LAUDA AIR WINTERFLUGPLAN 2009/2010 Das Lauda Air Winterflugprogramm 2009/2010 ist ab sofort buchbar. Neben "Klassikern" wie Antalya, Punta Cana und Funchal stehen auch Sonnenziele in Ägypten und auf den Kanaren am Flugplan. Neu ist ab diesem Winter, dass Kaum ein Thema hat die heimische Luftfahrtlandschaft in den letzten Monaten so bewegt wie es bis zu... mehr » der Verkauf der AUA an die Lufthansa – vielleicht einmal abgesehen von der Diskussion rund um den Skylink. Würden die einen den Deal lieber heute als morgen unter Dach und Fach wissen, sparen andere nicht mit deutlicher Kritik an dem Verkauf. Insbesondere die mögliche NIKI LAUDA WILL OSTSTRECKEN marktbeherrschende Stellung des künftigen AUA-Lufthansa-Konglomerats in Österreich ist so VON AUSTRIAN AIRLINES manchem ein Dorn im Auge. Wie "DerStandard" in der Freitags-Ausgabe So waren in den letzten Monaten vor allem zwei Personen sowohl in den Medien als auch bei meldet, möchte Niki Lauda die Hälfte der der EU-Kommission in Brüssel aktiv unterwegs: Zum einen sorgt sich Robin Hood-Chef Georg Osteuropa-Strecken von der AUA Pommer um den künftigen Bundesländerverkehr, zum anderen will Niki Lauda für seine Airline übernehmen. -

CORSIA Aeroplane Operator to State Attributions

CORSIA Aeroplane Operator to State Attributions This is a preliminary version of the ICAO document “CORSIA Aeroplane Operator to State Attributions” that has been prepared to support the timely implementation of CORSIA from 1 January 2019. It contains aeroplane operators with international flights, and to which State they are attributed, based on information reported by States by 30 November 2018 in accordance with the Environmental Technical Manual (Doc 9501), Volume IV – Procedures for Demonstrating Compliance with the CORSIA, Chapter 3, Table 3-1. Terms used in the tables on the following pages are: • Aeroplane Operator Name is the full name of the aeroplane operator as reported by the State; • Attribution Method is one of three options as selected by the State: "ICAO Designator", "Air Operator Certificate" or "Place of Juridical Registration" in accordance with Annex 16 – Environmental Protection, Volume IV – Carbon Offsetting and Reduction Scheme for International Aviation (CORSIA), Part II, Chapter 1, 1.2.4; and • Identifier is associated with each Attribution Method as reported by the State: o If the Attribution Method is "ICAO Designator", the Identifier is the aeroplane operator's three-letter designator according to ICAO Doc 8585; o If the Attribution Method is "Air Operator Certificate", the Identifier is the number of the AOC (or equivalent) of the aeroplane operator; o If the Attribution Method is "Place of Juridical Registration", the Identifier is the name of the State where the aeroplane operator is registered as juridical person. Disclaimer: The designations employed and the presentation of the material presented herein do not imply the expression of any opinion whatsoever on the part of ICAO concerning the legal status of any country, territory, city or area or of its authorities, or concerning the delimitation of its frontiers or boundaries. -

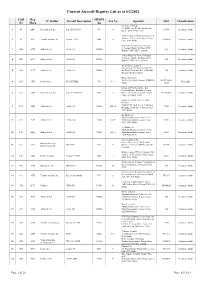

To Access the List of Registered Aircraft As on 2Nd August

Current Aircraft Registry List as at 8/2/2021 CofR Reg MTOM TC Holder Aircraft Description Pax No Operator MSN Classification No Mark /kg Cherokee 160 Ltd. 24, Id-Dwejra, De La Cruz Avenue, 1 41 ABW Piper Aircraft Inc. Piper PA-28-160 998 4 28-586 Aeroplane (land) Qormi QRM 2456, Malta Malta School of Flying Company Ltd. Aurora, 18, Triq Santa Marija, Luqa, 2 62 ACL Textron Aviation Inc. Cessna 172M 1043 4 17260955 Aeroplane (land) LQA 1643, Malta Airbus Financial Services Limited 6, George's Dock, 5th Floor, IFSC, 3 1584 ACX Airbus S.A.S. A340-313 275000 544 Aeroplane (land) Dublin 1, D01 K5C7,, Ireland Airbus Financial Services Limited 6, George's Dock, 5th Floor, IFSC, 4 1583 ACY Airbus S.A.S. A340-313 275000 582 Aeroplane (land) Dublin 1, D01 K5C7,, Ireland Air X Charter Limited SmartCity Malta, Building SCM 01, 5 1589 ACZ Airbus S.A.S. A340-313 275000 4th Floor, Units 401 403, SCM 1001, 590 Aeroplane (land) Ricasoli, Kalkara, Malta Nazzareno Psaila 40, Triq Is-Sejjieh, Naxxar, NXR1930, 001-PFA262- 6 105 ADX Reno Psaila RP-KESTREL 703 1+1 Microlight Malta 12665 European Pilot Academy Ltd. Falcon Alliance Building, Security 7 107 AEB Piper Aircraft Inc. Piper PA-34-200T 1999 6 Gate 1, Malta International Airport, 34-7870066 Aeroplane (land) Luqa LQA 4000, Malta Malta Air Travel Ltd. dba 'Malta MedAir' Camilleri Preziosi, Level 3, Valletta 8 134 AEO Airbus S.A.S. A320-214 75500 168+10 2768 Aeroplane (land) Building, South Street, Valletta VLT 1103, Malta Air Malta p.l.c. -

Ryanair to Partner with Niki Lauda to Develop Laudamotion Airline in Austria

50SKYSHADESImage not found or type unknown- aviation news RYANAIR TO PARTNER WITH NIKI LAUDA TO DEVELOP LAUDAMOTION AIRLINE IN AUSTRIA News / Airlines Image not found or type unknown Ryanair Holdings Plc today (20 Mar) announced that it has entered into a binding agreement with Mr Niki Lauda to support his plan to develop and grow LaudaMotion GmbH, an Austrian Airline based in Vienna. LaudaMotion is an Austrian AOC holder owned by Niki Lauda, which has recently acquired many© 2015-2021 of the 50SKYSHADES.COM assets, including — Reproduction, A320 aircraft, copying, or of redistribution the former for commercial Niki Airline, purposes and is prohibited. will shortly start1 a range of scheduled and charter services from Germany, Austria and Switzerland primarily to Mediterranean leisure destinations. Under this agreement Ryanair will acquire an initial 24.9% stake in LaudaMotion and this will rise as soon as possible to 75% subject to EU Competition approval. Niki Lauda will chair the Board of the airline and oversee the implementation of his strategy to build a successful Austrian low fares airline. Ryanair will provide financial and management support to LaudaMotion as well as 6 wet-lease aircraft for S2018 to enable LaudaMotion to complete an extensive 21 aircraft flying program. The cost of this 75% investment in LaudaMotion (if approved by the EU) will be less than €50m although Ryanair will provide an additional €50m for year 1 start up and operating costs. Both Mr Lauda and Ryanair will work with the existing management team of LaudaMotion and expect the airline to reach profitability by year 3 of operations if their plan to grow the business to a fleet of at least 30 Airbus aircraft is successful. -

Presentation of the Traffic Results for 2020 and Outlook

FLUGHAFEN WIEN AG Traffic Results 2020 and Business Outlook for 2021 Press Conference, 21 January 2021 2020: Most difficult year in the history of Vienna Airport – Upswing expected in 2021 Coronavirus pandemic comes close to bringing global flight operations to a standstill – passenger volumes down 60% across the globe (IATA estimate) 7.8 million passengers at Vienna Airport in 2020 (-75.3%) – like in the year 1994 The crisis has shown how indispensable air transport is: delivery of relief supplies, repatriation flights, Vienna Airport available 24/7 as part of the critical infrastructure Outlook for 2021: due to upturn in H2/2021 about 40% of pre-crisis level (12.5 million passengers) and expected consolidated net profit close to zero – short time work extended until March 2021 About 70% of pre-crisis level in 2022, approx. 80% in 2023 Vaccination will provide impetus to growth, but only with unified international and European travel regulations – digitalisation as a major opportunity (“digital vaccine certificate“) 2 Development in 2020 Traffic figures and influencing factors 3,500,000 PAX 2019 PAX 2020 14.4% 3,000,000 8.3% 2019 Deviation 2019/2020 2,500,000 2,000,000 1,500,000 1,000,000 -65.8% -74.7% -81.8% -81.1% -86.7% 500,000 -95.4% -93.4% -92.9% -99.5% -99.3% 2020 0 January February March April May June July August September October November December Begin of Travel warnings and 1st Insolvency First Passenger growth at restrictions on flight lockdown of Level Restart of “COVID- beginning of the year traffic Lauda Air Strongest Further tested “Lockdown End of Austrian Austrian and month travel flights“ light“, December: End of February: begin Repatriation flights, Airlines, Airlines Austrian thanks to warnings begin of beginning of first flight transport of relief Wizz Air resumes Airlines summer Antibody 2nd of 3rd cancellations (e.g. -

Annual Report 2007

EU_ENTWURF_08:00_ENTWURF_01 01.04.2026 13:07 Uhr Seite 1 Analyses of the European air transport market Annual Report 2007 EUROPEAN COMMISSION EU_ENTWURF_08:00_ENTWURF_01 01.04.2026 13:07 Uhr Seite 2 Air Transport and Airport Research Annual analyses of the European air transport market Annual Report 2007 German Aerospace Center Deutsches Zentrum German Aerospace für Luft- und Raumfahrt e.V. Center in the Helmholtz-Association Air Transport and Airport Research December 2008 Linder Hoehe 51147 Cologne Germany Head: Prof. Dr. Johannes Reichmuth Authors: Erik Grunewald, Amir Ayazkhani, Dr. Peter Berster, Gregor Bischoff, Prof. Dr. Hansjochen Ehmer, Dr. Marc Gelhausen, Wolfgang Grimme, Michael Hepting, Hermann Keimel, Petra Kokus, Dr. Peter Meincke, Holger Pabst, Dr. Janina Scheelhaase web: http://www.dlr.de/fw Annual Report 2007 2008-12-02 Release: 2.2 Page 1 Annual analyses of the European air transport market Annual Report 2007 Document Control Information Responsible project manager: DG Energy and Transport Project task: Annual analyses of the European air transport market 2007 EC contract number: TREN/05/MD/S07.74176 Release: 2.2 Save date: 2008-12-02 Total pages: 222 Change Log Release Date Changed Pages or Chapters Comments 1.2 2008-06-20 Final Report 2.0 2008-10-10 chapters 1,2,3 Final Report - full year 2007 draft 2.1 2008-11-20 chapters 1,2,3,5 Final updated Report 2.2 2008-12-02 all Layout items Disclaimer and copyright: This report has been carried out for the Directorate-General for Energy and Transport in the European Commission and expresses the opinion of the organisation undertaking the contract TREN/05/MD/S07.74176. -

Airline Alliances

AIRLINE ALLIANCES by Paul Stephen Dempsey Director, Institute of Air & Space Law McGill University Copyright © 2011 by Paul Stephen Dempsey Open Skies • 1992 - the United States concluded the first second generation “open skies” agreement with the Netherlands. It allowed KLM and any other Dutch carrier to fly to any point in the United States, and allowed U.S. carriers to fly to any point in the Netherlands, a country about the size of West Virginia. The U.S. was ideologically wedded to open markets, so the imbalance in traffic rights was of no concern. Moreover, opening up the Netherlands would allow KLM to drain traffic from surrounding airline networks, which would eventually encourage the surrounding airlines to ask their governments to sign “open skies” bilateral with the United States. • 1993 - the U.S. conferred antitrust immunity on the Wings Alliance between Northwest Airlines and KLM. The encirclement policy began to corrode resistance to liberalization as the sixth freedom traffic drain began to grow; soon Lufthansa, then Air France, were asking their governments to sign liberal bilaterals. • 1996 - Germany fell, followed by the Czech Republic, Italy, Portugal, the Slovak Republic, Malta, Poland. • 2001- the United States had concluded bilateral open skies agreements with 52 nations and concluded its first multilateral open skies agreement with Brunei, Chile, New Zealand and Singapore. • 2002 – France fell. • 2007 - The U.S. and E.U. concluded a multilateral “open skies” traffic agreement that liberalized everything but foreign ownership and cabotage. • 2011 – cumulatively, the U.S. had signed “open skies” bilaterals with more than100 States. Multilateral and Bilateral Air Transport Agreements • Section 5 of the Transit Agreement, and Section 6 of the Transport Agreement, provide: “Each contracting State reserves the right to withhold or revoke a certificate or permit to an air transport enterprise of another State in any case where it is not satisfied that substantial ownership and effective control are vested in nationals of a contracting State . -

The General Court Dismisses the Actions Brought by the Airline Niki

General Court of the European Union PRESS RELEASE No 54/15 Luxembourg, 13 May 2015 Judgments in Cases T-511/09 and T-162/10 Press and Information Niki Luftfahrt GmbH v Commission The General Court dismisses the actions brought by the airline Niki Luftfahrt against Lufthansa’s acquisition of Austrian Airlines and the restructuring aid granted by Austria to Austrian in that regard None of the arguments put forward by Niki is capable of casting doubt on the Commission’s authorisation of that concentration and that aid, which it granted subject to conditions Austrian Airlines is the largest Austrian airline.1 Its main hub is Vienna International Airport (Austria). Due to financial difficulties faced by Austrian Airlines, the Austrian State decided to privatise it in 2008 by selling its majority shareholding of 41.56%. The bid of Germany’s largest airline, Lufthansa, whose hubs are Frankfurt International Airport (Germany) and Munich airport (Germany), was retained.2 In exchange for the transfer of the shares held by the Austrian State, Lufthansa’s bid proposed (i) to pay a purchase price of €366 268.75, (ii) to grant a debtor warrant capable of giving rise to an additional payment of up to €162 million should Austrian Airlines’s financial situation improve and (iii) that the Austrian State3 pay Austrian Airlines a subsidy of €500 million by means of a securitisation structure to be used to increase the capital of Austrian Airlines. In addition, Lufthansa initiated a take-over bid for Austrian Airlines’s remaining floating shares, which more shareholders accepted than was required. -

Annual Report 2004/2005

DO & CO I THE GOURMET ENTERTAINMENT COMPANY ANNUAL REPORT 2004I 2005 Ladies and Gentlemen, I am pleased to present to you the DO & CO Annual International Event Catering also made a sterling Report for 2004/2005. Annual reports are not showing this past business year. The division put in normally what you would think of as entertaining an excellent performance in the Formula 1, one of reading. As “Gourmet Entertainers” we have tried to its culinary customers since 1992. It also managed change that by conveying as modern and “tasty” a the entire VIP hospitality operations at the European picture of our company group as possible. Soccer Championships in Portugal for the first time Business year 2004/2005 was one of the most in 2004. These highlights plus one or two other successful the DO & CO Group has ever had. Our prestigious sports events are featured on the total sales of over EUR 134 million set an all-time following pages, along with a host of private and sales record and boosted EBIT substantially over the corporate celebrations. year before, to EUR 3.45 million. The Division Restaurants & Bars is virtually on a We are clearly positioned on the market. The par with the other divisions. Of special note in this DO & CO Group brands stand for unsurpassed segment is the successful development of K.u.K. quality and innovative products. Our corporate Hofzuckerbäckerei Demel. With the restructuring of culture is flexible and is always open to new ideas. this legend long completed, the expansion phase These traits are probably what have enabled us to now begins. -

Lauda Contrails Copy

Three-time Formula One world champion Niki Lauda has tested himself as few have. On the racetrack. In the boardroom. In the sky. His is a will literally forged by fire. He knows what he wants and usually gets it. Whatever the obstacle. His high-profile journey has taken him to his present position as founder and CEO of Lauda Air. From its headquarters in Vienna, its leading-edge fleet provides scheduled flights to five continents and charter services to some of the world’s premier business and vacation destinations. As of April 2000, Lauda Air joins the 11-member Star Alliance Network, comprised of such well-known airlines as Air Canada, Lufthansa and United. So what’s left? “The next two years we really have to make the alliance work well, for us and for them,” Niki Lauda says. “Personally, as long as I’m enjoying myself and have new challenges, I’ll continue what I’m doing. If that changes, I will think of something else.” As he has before. Bombardier Contrails Magazine – March 2000 FORMULA ONE WORLD CHAMPIONSHIPS ’75 and ’77-Ferrari, ’84-McLaren GRAND PRIX WINS 3 South African GP (’76 and ’77-Ferrari, ’84-McLaren) 3 Dutch GP (’74 and ’77-Ferrari, ’85-McLaren) 3 British GP (’76-Ferrari, ’82 and ’84-McLaren) 2 Swedish GP (’75-Ferrari, ’78-Brabham) 2 Monaco GP (’75 and ’76-Ferrari) 2 French GP (’75-Ferrari, ’84-McLaren) Niki Lauda in his early 2 Belgian GP (’75 and ’76-Ferrari) 2 Italian GP (’78-Brabham, ’84-McLaren) 20s, prior to his 1975 s a young man, Niki Lauda to Formula One. -

Punctuality Statistics Economic Regulation Group Aviation Data Unit

Punctuality Statistics Economic Regulation Group Aviation Data Unit Birmingham, Edinburgh, Gatwick, Glasgow, Heathrow, London City, Luton, Manchester, Newcastle, Stansted Full and Summary Analysis December 2001 Disclaimer The information contained in this report will be compiled from various sources and it will not be possible for the CAA to check and verify whether it is accurate and correct nor does the CAA undertake to do so. Consequently the CAA cannot accept any liability for any financial loss caused by the persons reliance on it. Contents Foreword Introductory Notes Full Analysis – By Reporting Airport Birmingham Edinburgh Gatwick Glasgow Heathrow London City Luton Manchester Newcastle Stansted Full Analysis With Arrival / Departure Split – By A Origin / Destination Airport B C – E F – H I – L M – N O – P Q – S T – U V – Z Summary Analysis FOREWORD 1 CONTENT 1.1 Punctuality Statistics: Heathrow, Gatwick, Manchester, Glasgow, Birmingham, Luton, Stansted, Edinburgh, Newcastle and London City - Full and Summary Analysis is prepared by the Civil Aviation Authority with the co-operation of the airport operators and Airport Coordination Ltd. Their assistance is gratefully acknowledged. 2 ENQUIRIES 2.1 Statistics Enquiries concerning the information in this publication and distribution enquiries concerning orders and subscriptions should be addressed to: Civil Aviation Authority Room K4 G3 Aviation Data Unit CAA House 45/59 Kingsway London WC2B 6TE Tel. 020-7453-6258 or 020-7453-6252 or email [email protected] 2.2 Enquiries concerning further analysis of punctuality or other UK civil aviation statistics should be addressed to: Tel: 020-7453-6258 or 020-7453-6252 or email [email protected] Please note that we are unable to publish statistics or provide ad hoc data extracts at lower than monthly aggregate level. -

World Timetable

World timetable KLM & partners Book online at www.klm.com or call KLM Amsterdam + 31 20 4 747 747 24 hours a day, 7 days a week. Important This timetable presents schedule data available on May 25, 2004 Schedule changes are likely to occur after this date. We recommend that you obtain confirmation of all flight details when making reservations for your personal itinerary. Book online at www.klm.com or call KLM Amsterdam +31 20 4 747 747 24 hours a day, 7 days a week. Printing To print the page you are viewing, do NOT press the print button but go to the PRINT dialogue and select the page(s) you wish to print. If you do not do this, then the whole timetable will print out. Decoding Airline codes USA Two letter state codes AF Air France SB Air Caledonie International AK Alaska AM Aeromexico SU Aeroflot AL Alabama AS Alaska Airlines TA Taca International Airlines, S.A. AR Arkansas AT Royal Air Maroc TE Lithuanian Airline AZ Arizona AY Finnair Oyj TN Air Tahiti Nui CA California AZ Alitalia TU Tunis Air CO Colorado A5 Air Linair UU Air Austral CT Connecticut A6 Air Alps Aviation UX Air Europa DC District of Columbia BA British Airways VN Vietnam Airlines Corporation DE Delaware BD British Midland Airways Ltd VO Tyrolean Airways FL Florida BE British European WA KLM Cityhopper GA Georgia Bus Bus service WB Rwandair Express HI Hawaii CO Continental Airlines WX Cityjet dba Air France IA Iowa COe Continental Express XJ Mesaba Airlines (Northwest Airlink) ID Idaho CY Cyprus Airways XK Compagnie Aerienne Corse Mediterranee IL Illinois CZ China Southern Airlines XM Alitalia Express IN Indiana DB Brit Air dba Air France XT Air Exel dba KLM Exel KS Kansas DL Delta Air Lines YS Regional Airlines dba Air France KY Kentucky DM Maersk Air YW Air Nostrum L.A.M.S.A.