Bullying,Intimidation and Harassment Prevention School Policy

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

1 Kenneth Burke and the Theory of Scapegoating Charles K. Bellinger Words Sometimes Play Important Roles in Human History. I

Kenneth Burke and the Theory of Scapegoating Charles K. Bellinger Words sometimes play important roles in human history. I think, for example, of Martin Luther’s use of the word grace to shatter Medieval Catholicism, or the use of democracy as a rallying cry for the American colonists in their split with England, or Karl Marx’s vision of the proletariat as a class that would end all classes. More recently, freedom has been used as a mantra by those on the political left and the political right. If a president decides to go war, with the argument that freedom will be spread in the Middle East, then we are reminded once again of the power of words in shaping human actions. This is a notion upon which Kenneth Burke placed great stress as he painted a picture of human beings as word-intoxicated, symbol-using agents whose motives ought to be understood logologically, that is, from the perspective of our use and abuse of words. In the following pages, I will argue that there is a key word that has the potential to make a large impact on human life in the future, the word scapegoat. This word is already in common use, of course, but I suggest that it is something akin to a ticking bomb in that it has untapped potential to change the way human beings think and act. This potential has two main aspects: 1) the ambiguity of the word as it is used in various contexts, and 2) the sense in which the word lies on the boundary between human self-consciousness and unself-consciousness. -

Current Issues in Victimization Research and the NCVS's Ability To

Current Issues in Victimization Research and the NCVS’s Ability to Study Them Lynn A. Addington, J.D., Ph.D. Department of Justice, Law and Society American University Prepared for presentation at the Bureau of Justice Statistics Data User’s Workshop, February 12, 2008, Washington, D.C. Introduction and NCVS have played an essential role in shaping what researchers know about victimization as well as providing Thirty-five years have passed since the fielding of the first the national measure of criminal victimization for the National Crime Survey (NCS) and 15 years since its redesign United States.2 For the NCVS to continue in this crucial and emergence as the National Crime Victimization Survey and central role, it should be capable of serving the needs of (NCVS).1 This BJS Data Users Workshop presents a good, researchers, practitioners, and policymakers. Continuing to and much-needed, opportunity to examine how the survey meet the current needs of these various users of NCVS data has been (and could be) used in its present form as well as may require changes to the survey. to consider possible ways the survey could be changed to explore new issues of concern to victimization researchers. This paper has two primary aims. The first is to provide an Current Trends and Open Issues in overview of the current trends and issues in victimization Victimization Research research. Trends include topics that have attracted research Before examining specific issues, it is useful to place the attention as well as those yet to be fully explored as available current state of victimization research into a larger context. -

Power and Control Wheel NO SHADING

POOWERWER AANDND COONTROLNTROL WHHEELEEL hysical and sexual assaults, or threats to commit them, are the most apparent forms of domestic violence and are usually Pthe actions that allow others to become aware of the problem. However, regular use of other abusive behaviors by the batterer, when reinforced by one or more acts of physical violence, make up a larger system of abuse. Although physical as- saults may occur only once or occasionally, they instill threat of future violent attacks and allow the abuser to take control of the woman’s life and circumstances. he Power & Control diagram is a particularly helpful tool in understanding the overall pattern of abusive and violent be- Thaviors, which are used by a batterer to establish and maintain control over his partner. Very often, one or more violent incidents are accompanied by an array of these other types of abuse. They are less easily identified, yet firmly establish a pat- tern of intimidation and control in the relationship. VIOLENCE l a se sic x y COERCION u AND THREATS: INTIMIDATION: a h Making her afraid by p Making and/or carry- l ing out threats to do using looks, actions, something to hurt her. and gestures. Smashing Threatening to leave her, things. Destroying her commit suicide, or report property. Abusing pets. her to welfare. Making Displaying weapons. her drop charges. Making her do illegal things. MALE PRIVILEGE: EMOTIONAL ABUSE: Treating her like a servant: making Putting her down. Making her all the big decisions, acting like the feel bad about herself. “master of the castle,” being the Calling her names. -

Guidance on Voter Intimidation

BRIAN E. FROSH ELIZABETH F. HARRIS Attorney General Chief Deputy Attorney General CAROLYN QUATTROCKI Deputy Attorney General STATE OF MARYLAND OFFICE OF THE ATTORNEY GENERAL FACSIMILE NO. WRITER’S DIRECT DIAL NO. GUIDANCE ON VOTER INTIMIDATION This guidance seeks to inform Maryland voters about activities that are permitted versus prohibited at or near polling places, so that they know the difference and can safely exercise their right to vote. Whether certain conduct constitutes voter intimidation will depend on the specific facts in each case, but if you believe that you have witnessed or experienced voter intimidation, or that such conduct is imminent, please call the Office of the Attorney General at 443-961-2830 or toll free at 833-282-0960, or by email at [email protected]. For all other election-related concerns, contact the State Board of Elections by phone at 410-269-2840 or by email addressed to [email protected], or reach out to your local board or elections directly. A list of contact information for each local board of elections is available at https://www.elections.maryland.gov/about/county_boards.html. Finally, if there is violence or a threat of violence at a polling place, call 911 immediately. 1. What is voter intimidation? Voter intimidation is a crime under both Maryland and federal law. Under Maryland law, a person may not willfully and knowingly influence or attempt to influence a voter’s voting decision, or a voter’s decision whether to go to the polls to cast a vote, through the use of force, threat, menace, intimidation, bribery, reward, or offer of reward. -

Scapegoating As an Organizational Escape from Crisis: a Case Study of Merrill Lynch

Western Michigan University ScholarWorks at WMU Master's Theses Graduate College 8-2004 Scapegoating as an Organizational Escape from Crisis: A Case Study of Merrill Lynch Jennifer D. Brown Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarworks.wmich.edu/masters_theses Part of the Communication Commons Recommended Citation Brown, Jennifer D., "Scapegoating as an Organizational Escape from Crisis: A Case Study of Merrill Lynch" (2004). Master's Theses. 3988. https://scholarworks.wmich.edu/masters_theses/3988 This Masters Thesis-Open Access is brought to you for free and open access by the Graduate College at ScholarWorks at WMU. It has been accepted for inclusion in Master's Theses by an authorized administrator of ScholarWorks at WMU. For more information, please contact [email protected]. SCAPEGOATING AS AN ORGANIZATIONAL ESCAPE FROM CRISIS: A CASE STUDY OF MERRILL LYNCH by Jennifer D. Brown A Thesis Submitted to the Faculty of The Graduate College in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the Degree of Master of Arts Department of Communication Western Michigan University Kalamazoo, Michigan August 2004 ACKNOWLEDGMENTS It is with great pleasure that I write this page, because without each of these people in my life I would have never been able to complete my degree and fulfill my dreams. First to my esteemed advisor, Dr. Keith Hearit, thank you for the imprints you have left on my life over the past two years. Your amazing guidance, faith, and encouragement have helped me to make my work better, for that I am extremely grateful. Thank you for all of the hours you devoted to my thesis and I, both the knowledge and opportunities that you have provided me with will never be forgotten. -

1 May 2018 Human Rights Violations

MAY 2018 HUMAN RIGHTS VIOLATIONS 1 MAY 2018 HUMAN RIGHTS VIOLATIONS Ominous Internal political party processes ABOUT ZPP The organisation was founded in 2000 by church-based and Introduction and Statistical Analysis human rights organisations. The current members of ZPP are Evangelical Fellowship of Zimbabwe (EFZ), Zimbabwe Council The primary elections in the two main political of Churches (ZCC), Catholic Commission for Justice and Peace parties, Zanu PF and the MDC-T, continued to in Zimbabwe (CCJPZ), Counselling Services Unit (CSU), Zimbabwe Human Rights Association (ZimRights), Civic shape political events in May. (The MDC-T Education Network Trust (CIVNET), Zimbabwe Lawyers for held its primary elections in May, while for Human Rights (ZLHR) and Women’s Coalition of Zimbabwe (WCoZ). Zanu PF, they were mainly re-runs. Zanu PF’s primaries were in April). The primary elections ZPP was established with the objective of monitoring, nearly defined all the incidents of human rights documenting and building peace and promoting the peaceful resolution of disputes and conflicts. The Zimbabwe Peace violations in the month. Of the 81 cases that Project seeks to foster dialogue and political tolerance through were recorded in May, almost a 20 percent non-partisan peace monitoring activities, mainly through monitors who document the violations of rights in the provinces. decrease from the previous month where 102 The monitors, who at full complement stand at 477 including cases were recorded – over 75 percent of the Persons with Disability at District level, constitute the core pool cases were directly connected to the primary of volunteers, supported by four Regional Coordinators. -

Jick Student Violence / Harassment / Intimidation / Bullying

JICK STUDENT VIOLENCE / HARASSMENT / INTIMIDATION / BULLYING The Governing Board believes it is the right of every student to be educated in a positive, safe, caring, and respectful learning environment. The Board further believes a school environment inclusive of these traits maximizes student achievement, fosters student personal growth, and helps students build a sense of community that promotes positive participation as members of society. The District, in partnership with parents, guardians, and students, shall establish and maintain a school environment based on these beliefs. The District shall identify and implement age-appropriate programs designed to instill in students the values of positive interpersonal relationships, mutual respect, and appropriate conflict resolution. To assist in achieving a school environment based on the beliefs of the Governing Board, bullying, as set out in this policy and accompanying regulation, student harassment, intimidation and bullying are prohibited on school properly, on school buses, at school bus stops, and at school sponsored events and activities. Cyber harassment, intimidation and bullying are also prohibited. Distinction between harassment, intimidation and bullying may be found in Regulation JICK. The Superintendent shall establish procedures for the dissemination of information to students, parents, and guardians concerning this policy and accompanying regulation, incident reporting, support services (proactive and reactive) and student rights. Information will be provided to students, parents and guardians as follows: ● During the first week of each school year. ● To each incoming student during the school year at the time of the student's registration. ● In classrooms and in common areas of the school. ● Be summarized in the student handbook and on the District website. -

Workplace Culture and the Prevention of Workplace Bullying Andra Gumbus Sacred Heart University, [email protected]

Sacred Heart University DigitalCommons@SHU WCOB Faculty Publications Jack Welch College of Business 12-2012 Lean and Mean: Workplace Culture and the Prevention of Workplace Bullying Andra Gumbus Sacred Heart University, [email protected] Patricia Meglich University of Nebraska at Omaha Follow this and additional works at: http://digitalcommons.sacredheart.edu/wcob_fac Part of the Business Administration, Management, and Operations Commons, Human Resources Management Commons, and the Work, Economy and Organizations Commons Recommended Citation Gumbus, Andra and Meglich, Patricia, "Lean and Mean: Workplace Culture and the Prevention of Workplace Bullying" (2012). WCOB Faculty Publications. Paper 26. http://digitalcommons.sacredheart.edu/wcob_fac/26 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Jack Welch College of Business at DigitalCommons@SHU. It has been accepted for inclusion in WCOB Faculty Publications by an authorized administrator of DigitalCommons@SHU. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Lean and Mean: Workplace Culture and the Prevention of Workplace Bullying Andra Gumbus Sacred Heart University Patricia Meglich University of Nebraska at Omaha Workplace bullying has become a hot topic in the popular press as well as scholarly literature. Compared to targets of sexual harassment, bullied workers quit their jobs more often, are more unhappy, stressed at work, and less committed to the workplace. Little is done about it because there currently is no U.S. law against bullying and often the only recourse for targets is to quit their jobs. We present a case study and then review various legal remedies and sample company policies to explore the actions organizations might take to eliminate this destructive workplace behavior. -

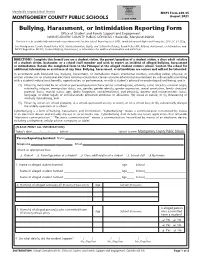

MCPS Bullying, Harassment, Or Intimidation Report Form

MCPS Form 230-35 August 2021 Bullying, Harassment, or Intimidation Reporting Form Office of Student and Family Support and Engagement MONTGOMERY COUNTY PUBLIC SCHOOLS • Rockville, Maryland 20850 This form is to be confidentially maintained in accordance with the Safe Schools Reporting Act of 2005, Family Educational Rights and Privacy Act, 20 U.S.C. § 1232g. See Montgomery County Board Policy ACA, Nondiscrimination, Equity, and Cultural Proficiency, Board Policy JHF, Bullying, Harassment, or Intimidation, and MCPS Regulation JHF-RA, Student Bullying, Harassment, or Intimidation for additional information and definitions. DIRECTIONS: Complete this form if you are a student victim, the parent/guardian of a student victim, a close adult relative of a student victim, bystander, or a school staff member and wish to report an incident of alleged bullying, harassment or intimidation. Return the completed form to the Principal at the alleged student victim’s school. Contact the school for additional information or assistance at any time. Bullying, harassment, or intimidation are serious and will not be tolerated. In accordance with Maryland law, bullying, harassment, or intimidation means intentional conduct, including verbal, physical, or written conduct or an intentional electronic communication that creates a hostile educational environment by substantially interfering with a student’s educational benefits, opportunities, or performance, or with a student’s physical or psychological well-being, and is: (1) Either (a) motivated by an actual -

Georgetown Law's Fact Sheet Protecting Against Voter Intimidation

for Constitutional Advocacy and Protection GEORGETOWN LAW Fact Sheet: Protecting Against Voter Intimidation Is voter intimidation illegal? Yes. The right of each voter to cast his or her ballot free from intimidation or coercion is a foundational principle of a free and democratic society. Federal law prohibits voter intimidation. Multiple federal statutes make it a crime to intimidate voters: it is illegal to intimidate, threaten, or coerce a person, or attempt to do so, “for the purpose of interfering with” that person’s right “to vote or to vote as he may choose.” 18 U.S.C. § 594. It is also a crime to knowingly and willfully intimidate, threaten, or coerce any person, or attempt to do so, for “registering to vote, or voting,” or for “urging or aiding” anyone to vote or register to vote. 52 U.S.C. § 20511(1). And it is a crime to “by force or threat of force” willfully injure, intimidate, or interfere with any person because he or she is voting or has voted or “in order to intimidate” anyone from voting. 18 U.S.C. § 245(b)(1)(A). Federal law also provides for civil lawsuits based on voter intimidation. Section 11 of the Voting Rights Act makes it unlawful to “intimidate, threaten, or coerce” another person, or attempt to do so, “for voting or attempting to vote” or “for urging or aiding any person to vote or attempt to vote.” 52 U.S.C. § 10307(b). And Section 2 of the Ku Klux Klan Act of 1871 makes it unlawful for “two or more persons to conspire to prevent by force, intimidation, or threat,” any voter from casting a ballot for the candidate of his or her choice. -

Domestic Violence / Intimate Partner Violence the Abuse Is Not Your Fault

Domestic Violence / Intimate Partner Violence The abuse is not your fault. The intent of abusive behavior is to achieve and maintain power and control over another. Abuse is a pattern of assaultive and coercive behaviors in which an adult or adolescent tries to control the thoughts, beliefs, or conduct of an intimate partner or person with a significant relationship to himself/herself. It can include but is not limited to the following abuses: Physical - Slap, punch, choke, or shove. Sexual - Forcing another to have sex against their will. Verbal - Threats, Humiliation, Intimidation, see below. Psychological/emotional - Verbal/nonverbal Threats, Humiliation, Intimidation, see below. Financial - Controlling the finances and withholding money, stealing from you, not allowing you to work, and sabotaging your job by making you miss work or calling constantly. The abuser may also exert power using the following tactics: Cultural - Abusers may threaten to call INS, misinform you about domestic violence laws in the U.S., use fear of police or government, steal/hide important documents (passport, visa etc.), kidnap or neglect the children, and turn the children against you. Dominance — Abusive individuals need to feel in charge of the relationship. They will make decisions and expect you to obey without question. Humiliation — An abuser may use insults, shaming or an public humiliation to erode your self- esteem and to make you feel powerless. Isolation — In order to increase your dependence on him/her, an abusive partner will cut you off from the outside world and keep you from seeing family, friends, or going to work or school. Threats — Abusers commonly use threats to keep their victims from leaving or to scare them into dropping charges. -

Dignity for All Students Act Guidance

The New York State Dignity for All Students Act: A Resource and Promising Practices Guide for School Administrators & Faculty Education Law, Article 2: The legislature finds that students’ ability to learn and to meet high standards, and a school’s ability to educate its students, are compromised by incidents of discrimination or harassment, including bullying, taunting or intimidation. It is hereby declared to be the policy of the state to afford all students in public schools an environment free of discrimination and harassment. The purpose of this article is to foster civility in public schools and to prevent and prohibit conduct which is inconsistent with a school’s educational mission. Revised 12/2017 TABLE OF CONTENTS Preface 3 Introduction 5 Section I School Climate and Culture 7 Section II Creating an Inclusive School Community: 16 Sensitivity to the Experience of Specific Student Populations Section III School Personnel including, Supervisors and Principals 27 Section IV The Dignity Act Coordinator 32 Section V Family and Parent Engagement: Communicating with the School Community 35 Section VI Restorative Approaches and Progressive Discipline 37 Section VII Internet Safety and Acceptable Use Policies 45 Section VIII Guidance on Bullying and Cyberbullying 46 _________________________________________________________________ Appendix A Dignity for All Students Act (Dignity Act) 51 Glossary and Acronym Guide Appendix B Federal Law Requiring Nondiscrimination Policies 61 2 Appendix C Selected Resources to Assist in the Implementation 62 of the Dignity Act Appendix D Selected Resources Consulted 83 Appendix E Dignity Act Task Force Members 84 3 PREFACE The New York State Dignity for All Students Act (Dignity Act): A Resource and Promising Practices Guide for School Administrators and Faculty was developed by the Dignity Act Task Force to assist schools in implementing the Dignity for All Students Act.