The Legacy of Andre Smith

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

VIST-Settlement

NOTICE OF PUBLIC HEARING NOTICE IS HEREBY GIVEN that a public hearing will be held by the Philadelphia Authority for Industrial Development (the “Authority”) at 10:00 a.m., on June 22, 2021 via conference call by dialing the toll-free number +1 (855) 633-2040 and then when prompted, passcode 2805224#. Due to the COVID-19 pandemic, the building that the Authority uses for its meetings is currently closed to the public, as such the meeting is open to the public via conference call only in accordance with Pennsylvania law (2020 Pa. Legis. Serv. Act 2020-15 (S.B. 841) (PURDON'S)) and the Governor’s Declaration of a State of Emergency for the Commonwealth of Pennsylvania dated March 6, 2020 due to a public health emergency, as amended by a First Amendment to Proclamation of Disaster Emergency dated June 3, 2020, a Second Amendment to Proclamation of Disaster Emergency dated August 31, 2020, a Third Amendment to Proclamation of Disaster Emergency dated November 24, 2020,a Fourth Amendment to Proclamation of Disaster Emergency dated February 19, 2021 and a Fifth Amendment to Amendment to Proclamation of Disaster Emergency dated May 20,2021. The purpose of the public hearing is to discuss to consider the proposed issuance of indebtedness (the “Note”) by the Horsham Industrial and Commercial Development Authority (“HICDA”) to finance a Project, as defined below. A. Borrower: Settlement Music School of Philadelphia, a Pennsylvania nonprofit corporation (“School”). B. Maximum Amount of the Note: Not anticipated to exceed $4,000,000.00. C. Project Locations: 416 Queen Street, Philadelphia, PA; 6128 Germantown Avenue, Philadelphia, PA; 3745 Clarendon Avenue, Philadelphia, PA; 4910 Wynnefield Avenue, Philadelphia, PA and 318 Davisville Road, Willow Grove, PA. -

Doctoral Dissertation Template

UNIVERSITY OF OKLAHOMA GRADUATE COLLEGE ALLISON NELSON: PIANIST, TEACHER AND EDITOR A DOCUMENT SUBMITTED TO THE GRADUATE FACULTY in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the Degree of DOCTOR OF MUSICAL ARTS By LYNN WORCESTER Norman, Oklahoma 2015 ALLISON NELSON: PIANIST, TEACHER AND EDITOR A DOCUMENT APPROVED FOR THE SCHOOL OF MUSIC BY ______________________________ Dr. Jane Magrath, Chair ______________________________ Dr. Stephen Beus, Co-Chair ______________________________ Dr. Barbara Fast ______________________________ Dr. Edward Gates ______________________________ Dr. Eugene Enrico ______________________________ Dr. Joseph Havlicek © Copyright by LYNN WORCESTER 2015 All Rights Reserved. ACKNOWLEDGMENTS This work would not have been possible without the guidance and support of the faculty members who served on my committee, Dr. Jane Magrath, Dr. Barbara Fast, Dr. Edward Gates, Dr. Eugene Enrico, Dr. Stephen Beus and Dr. Joseph Havlicek. To Dr. Jane Magrath: Thank you for your patience and continued support through every turn and for showing me how to be the finest professional I can be. Your guidance has allowed me to come in to my own as a pianist, teacher and writer. Special gratitude is reserved for Dr. Allison Nelson who shared her time, memories, and efforts over the course of this past year. Her wisdom, energy, and passion for music will stay with me for the rest of my life. Thank you to all of Dr. Nelson’s colleagues and former students who shared their time and participated in this study. A special thanks is owed to my family—my father, Mark Worcester, my mother, Eiki Worcester and my sister, Leya Worcester—whose love and dedication will always be cherished. -

Bold Intentions

BOLD INTENTIONS CURTIS INSTITUTE OF MUSIC STRATEGIC DIRECTION 2014–2024 EXTERNAL TRENDS ................................................................................................................................................ 2 CURTIS 2024 ............................................................................................................................................................. 3 BOLD INTENTIONS .................................................................................................................................................. 5 Mission, Core Values, Vision ............................................................................................................................. 5 Strategic Shifts ................................................................................................................................................... 7 Paths Not Pursued ............................................................................................................................................. 9 GOALS AND STRATEGIES ....................................................................................................................................... 10 Curtis Musician Life Cycle ............................................................................................................................... 11 Global Musical Community ............................................................................................................................. 16 Programs, Teaching Model and Experiential -

Curtis Institute of Music

C URTIS INST I TUT E O F MUS IC C ATA LOGU E 1 938- 1 939 R I T T E N H O U S E S Q U A R E P HI L A D E L P HI A P E NN S Y L V A NI A THE C RT S ST T TE OF M S C o ded U I IN I U U I , f un in 1 1 M o i e C i Bok e come 9 4 by ary L u s urt s , w l s f i i i students o all nat onal t es . Th e Curtis Institute receive s its support from Th e M o i e C i Bok Fo d i o i s ary L u s urt s un at n , operated under a Charter of th e Comm onwe alth of Pe i an d i s cc edi e d for th e nnsylvan a , fully a r t i c onferr ng of Degrees . Th e Curtis Institute i s approved by th e United State s Go vernment as an institution of learning for th e i i of n on - o o ei de tra n ng qu ta f r gn stu nts , in m A f 1 1 accordance with th e Im igration ct o 9 4 . T H E C U R T I S I N S T I T U T E O F M U S I C M ARY LOUISE CURTIS BOK ' Prcud mt CURTIS BOK Vice- President CARY W BOK Secretary LL PHILIP S . -

The Florida Historical Quarterly Published by the Florida Historical Society ·

LORIDA HISTORICAL QUARTERLY PUBLISHED BY THE FLORIDA HISTORICAL SOCIETY VOLUME 91 SUMMER 2012 NUMBER 1 The Florida Historical Quarterly Published by the Florida Historical Society · Connie L. Lester, Editor Daniel S. Murphree, Assistant Editor and Book Review Editor Robert Cassanello, Podcast Editor Sponsored by the University of Central Florida Board of Editors Jack Davis, University of Florida James M. Denham, Florida Southern College Andrew Frank, Florida State University Elna C. Green, Sanjose State University Steven Noll, University of Florida Raymond A. Mohl, University of Alabama, Birmingham Paul Ortiz, University of Florida Brian Rucker, Pensacola State College John David Smith, University of orth Carolina, Charlotte Melanie Shell-Weiss, Grand Valley University Brent Weisman, University of South Florida Irvin D.S. Winsboro, Florida Gulf Coast University The Florida Historical Quarterly (ISSN 0015-4113) is published quarterly by the Florida Historical Society, 435 Brevard Avenue, Cocoa, FL 32922 in cooperation with the Department of History, University of Central Florida, Orlando. Printed by The Sheridan Press, Hanover, PA. Periodicals postage paid at Cocoa, FL and additional mailing offices. POSTMASTER: Send address changes to the Florida Historical Society, 435 Brevard Ave., Cocoa, FL 32922. Subscription accompanies membership in the Society. Annual membership is $50; student membership (with proof of status) is $30; family membership in 75; library and institution membership is 75; a contributing membership is 200 and higher; and a corporate membership is 500 and higher. Correspondence relating to membership and subscriptions, as well as orders for back copies of the Quarterly, should be addressed to Dr. Ben D. Brotemarkle, Executive Director, Florida Historical Society, 435 Brevard Ave., Cocoa, FL 32922; (321) 690-1971; email: (Ben. -

DOWNLOAD Kaleidoscope HANDBOOK

KALEIDOSCOPE PRESCHOOL ARTS ENRICHMENT PROGRAM 2021-2022 PARENT HANDBOOK Music. Art. Dance. Mary Louise Curtis Branch Germantown Branch 416 Queen Street 6128 Germantown Avenue Philadelphia, PA 19147 Philadelphia, PA 19144 215-320-2670 215-320-2618 settlementmusic.org/kaleidoscope KALEIDOSCOPE PRESCHOOL ARTS ENRICHMENT PROGRAM 2021-2022 Parent Handbook Table of Contents School Calendar.........................................................................................................................................................................2 Parent Events Calendar .........................................................................................................................................................3 Contact Information ...............................................................................................................................................................4 Program Staff ..............................................................................................................................................................................4 General Information ................................................................................................................................................................5 Parent Information ...............................................................................................................................................................6-7 Supervision Policies ...........................................................................................................................................................8-9 -

Site Evaluations for the New Maitland Public Library

Comparative Site Evaluations for the New Maitland Public Library / '.\, MAITLAND PUBLIC LIBRARY “Show me your library and I’ll show you your future.” Daniel Taylor – Author, Writer, Traveler Prepared for: City of Maitland, Florida Prepared by: ACi Architects 07-31-2020 ■ Table of Contents MISSION AND VISION STATEMENTS INTRODUCTION INITIAL INFORMATION EXISTING LIBRARY SITE CONCEPTUAL BUILDING PROGRAM THE NEW AMERICAN PUBLIC LIBRARY SITE KEY PLAN SITE EVALUATION SITE EVALUATION CRITERIA SITE EVALUATIONS CANDIDATE SITE - HORATIO CANDIDATE SITE - QUINN STRONG PARK CANDIDATE SITE - LAKE LILY EVALUATION CRITERIA – RELATIVE IMPORTANCE AND SCORES EVALUATION CRITERIA SUMMARY EXECUTIVE SUMMARY Mission and Vision Statements The Maitland Public Library’s Vision Statement The mission of the Maitland Public Library is to connect the community to a world of opportunity. The Maitland Public Library’s Mission Statement To accomplish this mission, the Library will continually update its reading, viewing, and listening collections, as well as seek new ways to stimulate the intellectual growth of library users of all ages and provide a comfortable, usable environment in which patrons may access resources, obtain technical assistance, and find avenues to become discriminating consumers of contemporary information. Introduction Celebrating 124 years as a community organized library, today’s Maitland Public Library continues its vision and mission to support the city’s historic and future evolution as a community of culture, art, learning, commerce and recreation. Surrounded by its lakes, parks and neighborhoods, the historical significance of its early vision in the 19th century joined together many renown leaders, artists, wealthy entrepreneurs, tourists, philanthropists, and families from great American cities, towns and universities. -

Powder and Wig Will Present One-Act Plays Final Plans Released For

Powder And Wig Will Embassey Stresses Final Plans Released Nation's Unity Present One-Act Plays Brotherhood Week Will For Fraternity Embassy Be Observed Feb. 22-28 Students Will Direct Annua l Event To Take Coach Al McCoy In cooperation with the National Johnson Attends One Prod uction Conf erence of Jews and Christians, Place Februar y 24-26 Goes To Harvard Colby College will observe the week Defense Meeting of February 22-28, as National Many New Members Group Meetings To Accepts Coaching Berth Brotherhood Week. The theme of To Perform February 20 Brotherhood Week is national unity, Colleges Are Not To Be Highlight Program Under Crimson's Harlow and will honor the outstanding work Used As Training Camps The Powder and Wig will present of Charles Evans Hughes, Chief Jus- Final plans for the Interfraternity Coach Al McCoy resigned his posi- tice of the United States. Observed three plays on Thursday evening, President Franklin W. Johnson has Embassy to be held February 24, 25, tion at Colby to take up a new coach- annually throughout the nation dur- 2G February 20, at 8 P. M., in the Alum- recently attended a series , have been announced. Leaders ing post with Harvard University, it ing the week of Washington s birth- of confer- nae Building. ' ences of defense committees will arrive Monday and gather at a was announced late last Sunday by day. Brotherhood "Week received of col- Several experienced players,, well leges and universities in reception and tea in the Alumnae Gilbert P. Loebs, Director of Health the cooperation of over 2000 com- Washington, known to Colby dramatic circles, -will sponsored by the National Building at 4:00 in the afternoon. -

Curtis Publishing Company Records Ms

Curtis Publishing Company records Ms. Coll. 51 Finding aid prepared by Margaret Kruesi. Last updated on April 07, 2020. University of Pennsylvania, Kislak Center for Special Collections, Rare Books and Manuscripts 1992 Curtis Publishing Company records Table of Contents Summary Information....................................................................................................................................3 Biography/History..........................................................................................................................................4 Scope and Contents....................................................................................................................................... 7 Administrative Information........................................................................................................................... 7 Controlled Access Headings..........................................................................................................................8 Bibliography...................................................................................................................................................9 Collection Inventory.................................................................................................................................... 10 Ladies' Home Journal Correspondence.................................................................................................10 Ladies' Home Journal Remittances.......................................................................................................11 -

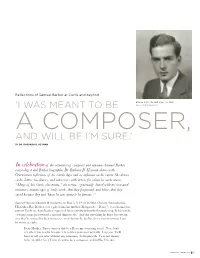

Reflections of Samuel Barber at Curtis and Beyond

Reflections of Samuel Barber at Curtis and beyond Barber in his student days, ca. 1932 ‘I WAS MEANT TO BE PHOTO: CURTIS ARCHIVES A COMPOSER, AND WILL BE I’M SURE.’ BY DR. BARBARA B. HEYMAN In celebration of the centenary of composer and alumnus Samuel Barber, musicologist and Barber biographer Dr. Barbara B. Heyman shares with Overtones reflections of his Curtis days and its influence on his career. She draws on his letters, his diaries, and interviews with artists for whom he wrote music. “Many of his Curtis classmates,” she writes, “generously shared with me treasured memories, manuscripts of early works that they performed, and letters that they saved because they just ‘knew he was going to be famous.’” Samuel Osmond Barber II was born on March 9, 1910, in West Chester, Pennsylvania. His father, Roy Barber, was a physician; his mother, Marguerite (“Daisy”), was an amateur pianist. Early on, Sam Barber expressed his creativity primarily through song. In his words, “writing songs just seemed a natural thing to do.” And the one thing he knew for certain was that he wanted to be a composer, an ambition he declared in a now-infamous letter he wrote at eight: Dear Mother: I have written this to tell you my worrying secret. Now don’t cry when you read it because it is neither yours nor my fault. I suppose I will have to tell you now without any nonsense. To begin with, I was not meant to be an athlet [sic]. I was meant to be a composer, and will be I’m sure. -

Jazz Identity and La Création Du Monde

THE OX IN THE CONCERT HALL: JAZZ IDENTITY AND LA CRÉATION DU MONDE Julio Moreno Gonzalez-Appling A Thesis Submitted to the Graduate College of Bowling Green State University in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of MASTER OF MUSIC December 2007 Committee: Robert Fallon, Advisor David Harnish Katherine Brucher ii ABSTRACT Dr. Robert Fallon, Advisor Darius Milhaud heard jazz for the first time in a London dance hall in 1919, and resolved to incorporate jazz into a chamber work. In America during the late 1910s, jazz was not yet a recognized genre, but rather was still a composite of several contributing styles. In Europe, however, ragtime, the blues, and American dance band music had fascinated modernist composers since the turn of the century. During his 1922 trip to the United States, Milhaud took every opportunity available to him to hear as much jazz as possible and found an outlet for his studies in the ballet La Création du monde, which premiered in Paris in 1923. The ballet opened to mixed reviews and French critics had little to say of Milhaud’s score. Ten years later, La Création received its American premiere and was hailed by American modernists as a precursor to the jazz works of Aaron Copland and superior to George Gershwin’s Rhapsody in Blue (1924). Milhaud’s La Création du monde has often been categorized as one of many modernist forays into jazz. Milhaud employed a distinctly different approach to jazz, however, than his contemporaries. He sought not only to imitate jazz gestures, but to understand jazz culturally. -

Concerts, Festivals, Food, and Eclectic Neighborhoods Put a Special Shine on Summer in Philadelphia

Clockwise from left: Philadelphia skyline, Silk City, Morgan’s Pier, and the O-bon Festival in Clark Park Season of Celebration n summertime, the streets of Philadelphia’s historic district are crowded with visitors looking to better understand IAmerica’s beginnings. Stops on this route of interwoven sites include the Liberty Bell, Independence Hall, Benjamin Franklin Museum, National Constitution Center, and Christ Church. They stitch together that fabled story as easily as Betsy Ross did the nation’s first flag. “Philadelphia’s enduring independent spirit was established in the historic district,” says Meryl Levitz, the president and CEO of VISIT PHILADEPHIATM. “Today, you find that revolu- tionary quality all over the region.” Beyond Philly’s historic heart, travelers gather deeper insights into the city’s past and a rich un- derstanding of this modern metropolitan area that some four million people are proud to call home. Start by exploring the neighborhoods within a Concerts, festivals, five-minute walk. To the north, Old City condos, art galleries, and happening restaurants are lo- food, and eclectic cated in redeveloped Civil War–era factories. A neighborhoods put PHOTOS BY J. FUSCO FOR VISIT PHILADELPHIA™ few blocks south, Society Hill features stately red brick homes with Federal touches such as boot a special shine scrapers, marble stoops, and wooden shutters. on summer in Hot Fun in the City Philadelphia. To the east lies Penn’s Landing, a hub of summer fun, including concerts, films, and, most notably, BY JOANN GRECO fireworks and other events linked to Wawa Wel- come America!, the city’s weeklong Independence 156 JUNE 2014 usairwaysmag.com usairwaysmag.com JUNE 2014 157 Day festival (July 1–7).