Alexandre Dumas (1802-1870)

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Black Tulip This Is No

Glx mbbis Digitized by the Internet Archive in 2018 with funding from University of Alberta Libraries https://archive.org/details/blacktulip00duma_0 EVERYMAN’S LIBRARY EDITED BY ERNEST RHYS FICTION THE BLACK TULIP THIS IS NO. 174 OF eFe%r31^3^S THE PUBLISHERS WILL BE PLEASED TO SEND FREELY TO ALL APPLICANTS A LIST OF THE PUBLISHED AND PROJECTED VOLUMES ARRANGED UNDER THE FOLLOWING SECTIONS: TRAVEL ^ SCIENCE ^ FICTION THEOLOGY & PHILOSOPHY HISTORY ^ CLASSICAL FOR YOUNG PEOPLE ESSAYS » ORATORY POETRY & DRAMA BIOGRAPHY REFERENCE ROMANCE THE ORDINARY EDITION IS BOUND IN CLOTH WITH GILT DESIGN AND COLOURED TOP. THERE IS ALSO A LIBRARY EDITION IN REINFORCED CLOTH J. M. DENT & SONS LTD. ALDINE HOUSE, BEDFORD STREET, LONDON, W.C.2 E. P. DUTTON & CO. INC. 286-302 FOURTH AVENUE, NEW YORK g^e BEAGK TULIPBY AISXANDRE DUMAS LONDON S' TORONTO J-M-DENTS'SONS LTD. ^ NEW YORK E P-DUTTON SCO First Published in this Edition . 1906 Reprinted.1909, 1911, 1915, 1919, 1923, 1927, 1931 PRINTED IN GREAT BRITAIN ( library OF THE IfMIVfRSITY I OF ALBERT^ il EDITOR’S NOTE La Tulipe Noire ” first appeared in 1850. Dumas was then nearing the end of his Monte Christo magnifi¬ cences, and about to go into a prodigal’s exile at Brussels. It is said that he was given the story, all brief, by King William the Third of Holland, whose coronation he did undoubtedly attend. It is much more probable, nay, it is fairly certain, that he owed it to his history-provider, Lacroix. An historical critic, however, has pointed out that in his fourth chapter, “ Les Massacreurs,” Dumas rather leads his readers to infer that that other William III., William of Orange, was the prime mover and moral agent in the murder of the De Witts. -

June 1962 Acknowledgments

A CRITICAL ANALYSIS OF FIVE POEMS BY ALFRED DE VIGNY "MOISE," "LA MAISON DU BERGER," "LA COLERE DE SAMSON," "LE MONT DES OLIVIERS," AND "LA MORT DU LOUP" A THESIS SUBMITTED TO THE FACULTY OF ATLANTA UNIVERSITY IN PARTIAL FULFILLMENT OF THE REQUIREMENTS FOR THE DEGREE OF MASTER OF ARTS BY ELAINE JOY C. RUSSELL DEPARTMENT OF FRENCH ATLANTA, GEORGIA JUNE 1962 ACKNOWLEDGMENTS In the preparation of this thesis I have received generous as sistance from many persons, and it is my wish to acknowledge their kind efforts. I am indebted to Doctor Benjamin F. Hudson, Chairman, Department of French, Atlanta University, to Mrs. Jacqueline Brimmer, Professor, Morehouse College, and to Mrs. Billie Geter Thomas, Head, Modern Language Department, Spelman College, for their kind and help ful suggestions. In addition to my professors, I wish to thank the Library staff, especially Mrs. Annabelle M. Jarrett, for all the kind assistance which I have received from them. ii TABLE OF CONTENTS Page ACKNOWLEDGMENTS ±± Chapter I. INTRODUCTION ! II. THE ORIGIN AND DEVELOPMENT OF THE ROMANTIC THEMES 5 III. THE FUNCTION OF THE POET 21 IV. THE PHILOSOPHY OF ALFRED DE VIGNI AS REVEALED IN: "LA MAISON DU BERGER, •' AND "LA COLERE DE SAMSON" 30 V. THE PHILOSOPHY OF ALFRED DE VIGNY AS REVEALED IN: »LE MONT DES OLIVIERS,» AND "LA. MORT DU LOUP" £2 Conclusion 5j^ BIBLIOGRAPHY 57 iii CHAPTER I INTRODUCTION Each literaiy movement develops its favorite themes. Love, death, religion, nature and nationalism became the great themes of the romantic period. The treatment of these themes by the precursors of romanticism was later interpreted and developed by the major romantic poets, Alphonse de Lamartine, Victor Hugo, Alfred de Musset and Alfred de Vigny. -

Gérard De Nerval Et Charles Nodier: Le Rêve Et La Folie

ABSTRACT GÉRARD DE NERVAL ET CHARLES NODIER: LE RÊVE ET LA FOLIE par Laetitia Gouhier Charles Nodier et Gérard de Nerval entreprennent dans La Fée aux miettes et Aurélia une exploration du moi et de la destinée de ce moi à la recherche d’une vérité transcendante qui est la quête du bonheur à travers une femme aimée irrémédiablement perdue. Pour cela ils développent un mode d’expression en marge des modes littéraires de l’époque en ayant recours au mode fantastique. En effet, l’exploration du moi est liée à la perception surnaturaliste intervenant dans les rêves des protagonistes de ces deux contes. Il s’agit dans cette étude de voir comment l’irruption de l’irréel chez Nodier et Nerval creuse un espace dans lequel instaurer le moi et pourquoi l’irréel et le fantastique provoquent l’interrogation du « moi » en littérature jetant un doute sur sa santé mentale. GÉRARD DE NERVAL ET CHARLES NODIER : LE RÊVE ET LA FOLIE A thesis Submitted to the Faculty of Miami University In partial fulfilment of The requirements of the degree of Masters of Arts Department of French and Italian By Laetitia Gouhier Miami University Oxford, Ohio 2003 Advisor: Jonathan Strauss Reader: Elisabeth Hodges Reader: Anna Roberts TABLE DES MATIÈRES Introduction: Gérard de Nerval le poète fou et Charles Nodier le conteur mélancolique................................................................................................................1 Petite histoire de la folie...........................................................................................2 Nerval -

31 Shades (& Counting) of Derby Gray

MONDAY, APRIL 26, 2021 CADDO RIVER OUT OF DERBY 31 SHADES (& COUNTING) Shortleaf Stable's 'TDN Rising Star' Caddo River (Hard Spun) OF DERBY GRAY will not make the line-up for Saturday's GI Kentucky Derby after spiking a fever over the weekend. AWe noticed he was off his feed and took his temperature yesterday afternoon. It was slightly elevated,@ trainer Brad Cox said. AIt=s just really bad timing being this close to the Derby. We drew blood on him [Sunday] morning and his white cell counts were a little high. We just can=t run him on Saturday with being a little off his game.@ The defection of the GI Arkansas Derby runner-up will allow GII Remsen S. winner Brooklyn Strong (Wicked Strong) to enter the Derby field. The Mark Schwartz colorbearer, most recently fifth in the Apr. 3 GII Wood Memorial, is scheduled to work at Parx Monday morning for trainer Daniel Velazquez and could ship into Churchill Downs Tuesday morning if all goes well. After sending his Derby quartet out to jog Sunday morning, trainer Todd Pletcher announced a Derby rider for Sainthood Giacomo | Horsephotos (Mshawish). Cont. p6 The Week in Review, by T.D. Thornton IN TDN EUROPE TODAY Gray horses have been in a GI Kentucky Derby rut the past 15 years. No fewer than 31 consecutive grays (or roans) have gone BARON SAMEDI TAKES THE VINTAGE CROP to post without winning on the first Saturday in May (or Baron Samedi won his sixth straight race and stamped himself a potential star of the staying ranks with a win in Sunday’s G3 September) since Giacomo roared home in front at 50-1 in 2005. -

THE THREE MUSKETEERS by Alexandre Dumas

THE THREE MUSKETEERS by Alexandre Dumas THE AUTHOR Alexandre Dumas (1802-1870) was born in a small French village northeast of Paris. His father had been a general under Napoleon, and his paternal grandfather had lived in Haiti and had married a former slave woman there, thus making Dumas what was called a quadroon. Napoleon and his father had parted on bad terms, with Dumas’ father being owed a large sum of money; the failure to pay this debt left the family poor and struggling, though the younger Dumas remained an admirer of the French emperor. Young Dumas moved to Paris in 1823 and took a job as a clerk to the Duke of Orleans (later to become King Louis Philippe), but soon began writing plays. Though his plays were successful and he made quite a handsome living from them, his profligate lifestyle (both financially and sexually) kept him constantly on the edge of bankruptcy. He played an active role in the revolution of 1830, and then turned to writing novels. As was the case with Dickens in England, his books were published in cheap newspapers in serial form. Dumas proved able to crank out popular stories at an amazing rate, and soon became the most famous writer in France. Among his works are The Three Musketeers (1844), The Count of Monte Cristo (1845), and The Man in the Iron Mask (1850). Dumas’ novels tend to be long and full of flowery description (some cynics suggest that this is because he was paid by the word), and for this reason often appear today in the form of abridged translations (if you ever doubt the value of such an approach, take a look at the unabridged version of Victor Hugo’s Les Miserables sometime). -

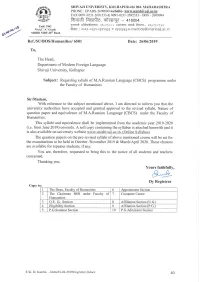

M.A. Russian 2019

************ B+ Accredited By NAAC Syllabus For Master of Arts (Part I and II) (Subject to the modifications to be made from time to time) Syllabus to be implemented from June 2019 onwards. 2 Shivaji University, Kolhapur Revised Syllabus For Master of Arts 1. TITLE : M.A. in Russian Language under the Faculty of Arts 2. YEAR OF IMPLEMENTATION: New Syllabus will be implemented from the academic year 2019-20 i.e. June 2019 onwards. 3. PREAMBLE:- 4. GENERAL OBJECTIVES OF THE COURSE: 1) To arrive at a high level competence in written and oral language skills. 2) To instill in the learner a critical appreciation of literary works. 3) To give the learners a wide spectrum of both theoretical and applied knowledge to equip them for professional exigencies. 4) To foster an intercultural dialogue by making the learner aware of both the source and the target culture. 5) To develop scientific thinking in the learners and prepare them for research. 6) To encourage an interdisciplinary approach for cross-pollination of ideas. 5. DURATION • The course shall be a full time course. • The duration of course shall be of Two years i.e. Four Semesters. 6. PATTERN:- Pattern of Examination will be Semester (Credit System). 7. FEE STRUCTURE:- (as applicable to regular course) i) Entrance Examination Fee (If applicable)- Rs -------------- (Not refundable) ii) Course Fee- Particulars Rupees Tuition Fee Rs. Laboratory Fee Rs. Semester fee- Per Total Rs. student Other fee will be applicable as per University rules/norms. 8. IMPLEMENTATION OF FEE STRUCTURE:- For Part I - From academic year 2019 onwards. -

Nineteenth-Century French Challenges to the Liberal Image of Russia

Ezequiel Adamovsky Russia as a Space of Hope: Nineteenth-century French Challenges to the Liberal Image of Russia Introduction Beginning with Montesquieu’s De l’esprit des lois, a particular perception of Russia emerged in France. To the traditional nega- tive image of Russia as a space of brutality and backwardness, Montesquieu now added a new insight into her ‘sociological’ otherness. In De l’esprit des lois Russia was characterized as a space marked by an absence. The missing element in Russian society was the independent intermediate corps that in other parts of Europe were the guardians of freedom. Thus, Russia’s back- wardness was explained by the lack of the very element that made Western Europe’s superiority. A similar conceptual frame was to become predominant in the French liberal tradition’s perception of Russia. After the disillusion in the progressive role of enlight- ened despotism — one must remember here Voltaire and the myth of Peter the Great and Catherine II — the French liberals went back to ‘sociological’ explanations of Russia’s backward- ness. However, for later liberals such as Diderot, Volney, Mably, Levesque or Louis-Philippe de Ségur the missing element was not so much the intermediate corps as the ‘third estate’.1 In the turn of liberalism from noble to bourgeois, the third estate — and later the ‘middle class’ — was thought to be the ‘yeast of freedom’ and the origin of progress and civilization. In the nineteenth century this liberal-bourgeois dichotomy of barbarian Russia (lacking a middle class) vs civilized Western Europe (the home of the middle class) became hegemonic in the mental map of French thought.2 European History Quarterly Copyright © 2003 SAGE Publications, London, Thousand Oaks, CA and New Delhi, Vol. -

The Meditations of Marcus Aurelius Antoninus

The meditations of Marcus Aurelius Antoninus Originally translated by Meric Casaubon About this edition Marcus Aurelius Antoninus Augustus was Emperor of Rome from 161 to his death, the last of the “Five Good Emperors.” He was nephew, son-in-law, and adoptive son of Antonius Pius. Marcus Aurelius was one of the most important Stoic philosophers, cited by H.P. Blavatsky amongst famous classic sages and writers such as Plato, Eu- ripides, Socrates, Aristophanes, Pindar, Plutarch, Isocrates, Diodorus, Cicero, and Epictetus.1 This edition was originally translated out of the Greek by Meric Casaubon in 1634 as “The Golden Book of Marcus Aurelius,” with an Introduction by W.H.D. Rouse. It was subsequently edited by Ernest Rhys. London: J.M. Dent & Co; New York: E.P. Dutton & Co, 1906; Everyman’s Library. 1 Cf. Blavatsky Collected Writings, (THE ORIGIN OF THE MYSTERIES) XIV p. 257 Marcus Aurelius' Meditations - tr. Casaubon v. 8.16, uploaded to www.philaletheians.co.uk, 14 July 2013 Page 1 of 128 LIVING THE LIFE SERIES MEDITATIONS OF MARCUS AURELIUS Chief English translations of Marcus Aurelius Meric Casaubon, 1634; Jeremy Collier, 1701; James Thomson, 1747; R. Graves, 1792; H. McCormac, 1844; George Long, 1862; G.H. Rendall, 1898; and J. Jackson, 1906. Renan’s “Marc-Aurèle” — in his “History of the Origins of Christianity,” which ap- peared in 1882 — is the most vital and original book to be had relating to the time of Marcus Aurelius. Pater’s “Marius the Epicurean” forms another outside commentary, which is of service in the imaginative attempt to create again the period.2 Contents Introduction 3 THE FIRST BOOK 12 THE SECOND BOOK 19 THE THIRD BOOK 23 THE FOURTH BOOK 29 THE FIFTH BOOK 38 THE SIXTH BOOK 47 THE SEVENTH BOOK 57 THE EIGHTH BOOK 67 THE NINTH BOOK 77 THE TENTH BOOK 86 THE ELEVENTH BOOK 96 THE TWELFTH BOOK 104 Appendix 110 Notes 122 Glossary 123 A parting thought 128 2 [Brought forward from p. -

Young Adult Realistic Fiction Book List

Young Adult Realistic Fiction Book List Denotes new titles recently added to the list while the severity of her older sister's injuries Abuse and the urging of her younger sister, their uncle, and a friend tempt her to testify against Anderson, Laurie Halse him, her mother and other well-meaning Speak adults persuade her to claim responsibility. A traumatic event in the (Mature) (2007) summer has a devastating effect on Melinda's freshman Flinn, Alexandra year of high school. (2002) Breathing Underwater Sent to counseling for hitting his Avasthi, Swati girlfriend, Caitlin, and ordered to Split keep a journal, A teenaged boy thrown out of his 16-year-old Nick examines his controlling house by his abusive father goes behavior and anger and describes living with to live with his older brother, his abusive father. (2001) who ran away from home years earlier under similar circumstances. (Summary McCormick, Patricia from Follett Destiny, November 2010). Sold Thirteen-year-old Lakshmi Draper, Sharon leaves her poor mountain Forged by Fire home in Nepal thinking that Teenaged Gerald, who has she is to work in the city as a spent years protecting his maid only to find that she has fragile half-sister from their been sold into the sex slave trade in India and abusive father, faces the that there is no hope of escape. (2006) prospect of one final confrontation before the problem can be solved. McMurchy-Barber, Gina Free as a Bird Erskine, Kathryn Eight-year-old Ruby Jean Sharp, Quaking born with Down syndrome, is In a Pennsylvania town where anti- placed in Woodlands School in war sentiments are treated with New Westminster, British contempt and violence, Matt, a Columbia, after the death of her grandmother fourteen-year-old girl living with a Quaker who took care of her, and she learns to family, deals with the demons of her past as survive every kind of abuse before she is she battles bullies of the present, eventually placed in a program designed to help her live learning to trust in others as well as her. -

François-Auguste-René, Vicomte De Chateaubriand

1 “TO BE CHATEAUBRIAND OR NOTHING”: FRANÇOIS-AUGUSTE-RENÉ, VICOMTE DE CHATEAUBRIAND “NARRATIVE HISTORY” AMOUNTS TO FABULATION, THE REAL STUFF BEING MERE CHRONOLOGY 1. Victor Hugo has been found guilty of scribbling “To be Chateaubriand or nothing” in one of his notebooks (but in his defense, when he scribbled this he was young). HDT WHAT? INDEX FRANÇOIS-AUGUSTE-RENÉ VICOMTE DE CHATEAUBRIAND 1768 September 4, Sunday: François-Auguste-René de Chateaubriand was born in Saint-Malo, the last of ten children of René de Chateaubriand (1718-1786), a ship owner and slavetrader. He would be reared in the family castle at Combourg, Brittany and then educated in Dol, Rennes, and Dinan, France. NOBODY COULD GUESS WHAT WOULD HAPPEN NEXT François-Auguste-René “Stack of the Artist of Kouroo” Project HDT WHAT? INDEX FRANÇOIS-AUGUSTE-RENÉ VICOMTE DE CHATEAUBRIAND 1785 At the age of 17 François-Auguste-René, vicomte de Chateaubriand, who had been undecided whether to become a naval officer or a priest, was offered a commission as a 2d lieutenant in the French Army based at Navarre. LIFE IS LIVED FORWARD BUT UNDERSTOOD BACKWARD? — NO, THAT’S GIVING TOO MUCH TO THE HISTORIAN’S STORIES. LIFE ISN’T TO BE UNDERSTOOD EITHER FORWARD OR BACKWARD. François-Auguste-René “Stack of the Artist of Kouroo” Project HDT WHAT? INDEX FRANÇOIS-AUGUSTE-RENÉ VICOMTE DE CHATEAUBRIAND 1787 By this point François-Auguste-René, vicomte de Chateaubriand had risen to the rank of captain in the French army. THE FUTURE IS MOST READILY PREDICTED IN RETROSPECT François-Auguste-René “Stack of the Artist of Kouroo” Project HDT WHAT? INDEX FRANÇOIS-AUGUSTE-RENÉ VICOMTE DE CHATEAUBRIAND 1788 François-Auguste-René, vicomte de Chateaubriand visited Paris and there made the acquaintance of a number of the leading writers of the era, such as Jean-François de La Harpe, André Chénier, and Louis-Marcelin de Fontanes. -

Socialist Realism Seen in Maxim Gorky's Play The

SOCIALIST REALISM SEEN IN MAXIM GORKY’S PLAY THE LOWER DEPTHS AN UNDERGRADUATE THESIS Presented as Partial Fulfilment of the Requirements for the Degree of Sarjana Sastra in English Letters By AINUL LISA Student Number: 014214114 ENGLISH LETTERS STUDY PROGRAMME DEPARTMENT OF ENGLISH LETTERS FACULTY OF LETTERS SANATA DHARMA UNIVERSITY YOGYAKARTA 2009 SOCIALIST REALISM SEEN IN MAXIM GORKY’S PLAY THE LOWER DEPTHS AN UNDERGRADUATE THESIS Presented as Partial Fulfilment of the Requirements for the Degree of Sarjana Sastra in English Letters By AINUL LISA Student Number: 014214114 ENGLISH LETTERS STUDY PROGRAMME DEPARTMENT OF ENGLISH LETTERS FACULTY OF LETTERS SANATA DHARMA UNIVERSITY YOGYAKARTA 2009 i ii iii HHaappppiinneessss aallwwaayyss llooookkss ssmmaallll wwhhiillee yyoouu hhoolldd iitt iinn yyoouurr hhaannddss,, bbuutt lleett iitt ggoo,, aanndd yyoouu lleeaarrnn aatt oonnccee hhooww bbiigg aanndd pprreecciioouuss iitt iiss.. (Maxiim Gorky) iv Thiis Undergraduatte Thesiis iis dediicatted tto:: My Dear Mom and Dad,, My Belloved Brotther and Siistters.. v vi ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS Firstly, I would like to praise Allah SWT for the blessings during the long process of this undergraduate thesis writing. I would also like to thank my patient and supportive father and mother for upholding me, giving me adequate facilities all through my study, and encouragement during the writing of this undergraduate thesis, my brother and sisters, who are always there to listen to all of my problems. I am very grateful to my advisor Gabriel Fajar Sasmita Aji, S.S., M.Hum. for helping me doing my undergraduate thesis with his advice, guidance, and patience during the writing of my undergraduate thesis. My gratitude also goes to my co-advisor Dewi Widyastuti, S.Pd., M.Hum. -

27 Lectures De La Reine Margot D'alexandre Dumas: Le Roman Populaire Par Excellence an Analytical Reading of Alexandre Dumas'

Jordan Journal of Modern Languages and Literature Vol.10, No. 1, 2018, pp 27-46 JJMLL Lectures de la Reine Margot d’Alexandre Dumas: le roman populaire par excellence Mohammad Matarneh Département de français, Université de Jordanie, Aqaba, Jordanie. Received on: 6-12-2017 Accepted on: 21-3-2018 Résumé Si Alexandre Dumas n'est pas le précurseur du roman historique tel que Georges Lukács l'a défini (Walter Scott l'a précédé), il en est le représentant français le plus illustre. L'auteur des Trois Mousquetaires a trouvé dans ce genre nouveau l'instrument parfait pour toucher les masses et les élever moralement. Avec La Reine Margot, il donne au public l'une des œuvres les plus accomplies qu'il ait conçues pour mener à bien son projet d'éducation populaire. Les données historiques de la Saint-Barthélemy, mais plus encore son savoir-faire de romancier en matière de création de personnages et d'incarnation de grands sujets de réflexion, font de cette œuvre l'un des meilleurs exemples pour définir l'esthétique et l'ambition dumassiennes. Mots clefs: Populaire, Margot, exploitation littéraire, personnages historiques, amour, amitié, mort. An analytical reading of Alexandre Dumas' Queen Margot: A distinguished popular novel Abstract Alexandre Dumas put aside the scholarly writing of history and chose instead the genre of popular novel in order to teach the French and other people history. He, thus, presents French national history in an entertaining and accessible way in La Reine Margot (Queen Margot), in which he popularizes great figures in French history. La Reine Margot is a clear example through which Dumas achieves his goal of teaching people the history of France.