Copyrighted Material

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Continuation Sheet Historic District Branford, Connecticut

NPS Form 10-900 OUB No. 1024-0018 (Rev. 8-86) United States Department of the Interior National Park Service NOV 1 4 1988 National Register of Historic Places Registration Form NATIONAL REGISTER This form is for use in nominating or requesting determinations of eligibility for individual properties or districts. See instructions in Guidelines for Completing National Register Forms (National Register Bulletin 16). Complete each item by marking "x" in the appropriate box or by entering the requested information. If an item does not apply to the property being documented, enter "N/A" for "not applicable." For functions, styles, materials, and areas of significance, enter only the categories and subcategories listed in the instructions. For additional space use continuation sheets (Form 10-900a). Type all entries. 1. Name of Property_________________________________________________ historic name other names/site number Stony Creek/Thimble Islands Historic District 2. Location street & number See continuation sheets I I not for publication city, town Branford T I vicinity" stateConnecticut code 09 county New Haven code 009 zip code 06405 3. Classification Ownership of Property Category of Property Number of Resources within Property |X2l private I I building(s) Contributing Noncontributing lot public-local |X}| district 14.1 buildings I I public-State Flsite 1 sites I I public-Federal I I structure structures I I object . objects 355 142 Total Name of related multiple property listing: Number of contributing resources previously N/A _____________________ listed in the National Register 1____ 4. State/Federal Agency Certification As the designated authority under the National Historic Preservation Act of 1966, as amended, I hereby certify that this [x~l nomination EH request for determination of eligibility meets the documentation standards for registering properties in the National Register of Historic Places and meets the procedural and professional requirements set forth in 36 CFR Part 60. -

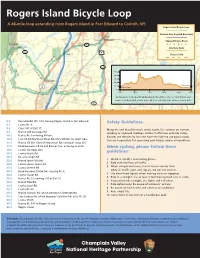

Rogers Island Bicycle Loop South Shore Rd

327 Terrebonne SStt.. 158 Bois-des-Filion LLaawwrreennccee RRiivveerr 132 Pointe-aux-Trembles Varennes Saint-Amable 116 125 224 Sainte-Thérèse 50 148 Rosemère Montréal-Est 40 15 Saint-Hyacinthe 640 138 440 25 223 Sainte-Julie 20 344 Saint-Léonard Boucherville 229 40 Beloeil LLaaccddeess 148 OOuuttaarrddeess Laval-Ouest Mont-Saint-Hilaire 417 117 Ferry St-Valérien 344 13 116 Longueuil 137 La Montréal Route Ve Ottawa rte Ottawa Sainte-Marthe-sur-le-Lac Aéroport Saint-Basile-le-Grand RRiivveerr Mont-Royal Aéroport SSaaiinntt--HHuubbeerrtt Outremont Landmark Bridge Saint-Laurent ddee LLoonngguueeuuiill L'Île-Bizard Dollard-des-Ormeaux Greenfield 231 342 Aéroport International Westmount Park 133 Aéroport International Saint-Hubert PPiieerrrree--EElllliiootttt--TTrruuddeeaauu Saint-Lambert Saint-Mathias-sur-Richelieu RRiivveeiirree Côte YYaammaasskkaa ddee MM 30 Saint-Luc La Pierrefonds Pointe-Claire Route Verte Kirkland 20 Montréal-Ouest Verdun Brossard 235 233 Sainte-Anne-de-Bellevue Lachine 134 Chambly 40 Beaconsfield Canton-de-Granby Lasalle 201 Terrasse-Vaudreuil La Prairie Vaudreuil-Dorion 10 112 L'Île-Perrot Candiac Notre-Dame-de-l'Île-Perrot 227 La Route Verte Route La 104 Pincourt 139 Maple 35 Saint-Constant Granby Grove Saint-Jean-sur-Richelieu 132 338 Melocheville 340 Grande-Île Saint-Timothée 207 20 Farnham 30 104 325 Cartiers Jacques Rue 241 221 Montee de la Cannerie 15 Salaberry-de-Valleyfield 217 Rue Principale 223 236 Saint-Jean-Baptiste rand 401 Ch. G Bernier Eglise l’ 219 e 235 Rue d Cowansville 132 209 205 Mtee Blais 223 Rg. St. Jo se ph 133 203 202 201 138 Mont Guay 225 St. -

Fort Edward / Rogers Island History and Timeline

HISTORY OF FORT EDWARD AND ROGERS ISLAND The present village of Fort Edward, New York, was called “The Great Carrying Place” because it was the portage between the Hudson River and Lake Champlain. The first recorded military expedition to have passed through the Great Carrying Place, led by Major General Fitz-John Winthrop, occurred in 1690. The following year, Peter Schuyler led another expedition against Canada. The first fortification to have been built in Fort Edward was under the command of Colonel Francis Nicholson in 1709, during the conflict known as “Queen Anne’s War.” Fort Nicholson was garrisoned by 450 men, including seven companies of “regulars in scarlet uniform from old England.” A crude stockade was built to protect storehouses and log huts. John Henry Lydius, a Dutch fur trader, came to the site of Fort Nicholson to construct a trading post in 1731. Lydius claimed this land under a title granted to the Rev. Dellius in 1696. According to a 1732 French map, the trading post may have been surrounded by storehouses and fortified. Lydius may also have built a sawmill on Rogers Island. It is unknown whether the Lydius post was destroyed and later reconstructed in 1745 when many French and Indian raids were being conducted on the Hudson River. Many Provincial troops arrived at the Great Carrying Place during July and August of 1755. Among these were the celebrated Rogers’ Rangers. Rogers Island became the base camp for the Rangers for about 2 ½ years during the French and Indian War. Many Ranger huts, a blockhouse, a large barracks complex, and a large smallpox hospital were constructed on Rogers Island between 1756 and 1759. -

Washington County, New York Data Book

Washington County, New York Data Book 2008 Prepared by the Washington County Department of Planning & Community Development Comments, suggestions and corrections are welcomed and encouraged. Please contact the Department at (518) 746-2290 or [email protected] Table of Contents: Table of Contents: ....................................................................................................................................................................................... ii Profile: ........................................................................................................................................................................................................ 1 Location & General Description .............................................................................................................................................................. 1 Municipality ............................................................................................................................................................................................. 3 Physical Description ............................................................................................................................................................................... 4 Quality of Life: ............................................................................................................................................................................................ 5 Housing ................................................................................................................................................................................................. -

2020 Hudson River Access Plan Poughkeepsie to Rensselaer

2020 HUDSON RIVER ACCESS PLAN POUGHKEEPSIE TO RENSSELAER FINAL REPORT GEORGE STAFFORD MARCH 2020 Photo courtesy of Jeanne Casatelli ACKNOWLEDGMENTS Hundreds of individuals, elected officials, agencies and organizations have contributed to the development of this document through their words and actions. They include: • People passionate about improved access to the Hudson River who attended public meetings, provided more than 1,000 comments and 5,000 votes on places where they use or wish to use the river, and have been directly involved in keeping access points open by taking part in cleanups along the shorelines and other activities. • Elected federal, state and local officials from Poughkeepsie to Rensselaer who provided letters and resolutions contained in this report, participated in phone interviews, facilitated public meeting sites, and elevated the importance of saving and increasing access points through their support of local plans and reports issued in recent years. • Individuals and organizations who collaborated on the Hudson River Access Forum that issued “Between the Railroad and the River—Public Access Issues and Opportunities along the Tidal Hudson.” This 1989 publication remains extremely relevant. • Finally, we wish to thank Matthew Atkinson, who authored “On the Wrong Side of the Railroad Tracks: Public Access to the Hudson River” (1996) for the Pace Environmental Law Review. This work provides a phenomenal review of the public trust doctrine and the legal principles governing the railroads’ obligation to provide river access. Mr. Atkinson’s advice during the development of this document proved invaluable. CONTACT / PRIMARY AUTHORS CONTACT Jeffrey Anzevino, AICP Director of Land Use Advocacy Scenic Hudson, Inc. -

2021 Saratoga County Official Directory

Saratoga County New York 2021 Official County, Town, City & Village Officers Directory Saratoga County A Brief History By Lauren Roberts, County Historian Saratoga County was formed from lands previously belonging to Albany County on February 7, 1791. These lands included most of the Kayaderosseras Patent granted by Queen Anne to 13 of her “loving subjects” in 1708. Saratoga County occupies an important geographical position; bounded on the north and east by the Hudson River and the south by the Mohawk River, the confluence of these two great waterways have made the County a prime destination in times of both war and peace. The northwestern portion of the county is a mountainous area located within the Adirondack Park, while many important rivers and streams such as the Sacandaga and Kayaderosseras dominate the fertile valley areas. The diverse geography of this County has made it appealing to many different people who have chosen to call Saratoga County home. The Mohawks of the Iroquois Confederacy used this area as hunting and fishing grounds before the Europeans settled here. Many waterways and well-worn Native American trails were used during the French and Indian War (1755-1763) and during the American Revolution. In the Fall of 1777 British troops led by General John Burgoyne were headed south along the Hudson River when they encountered a large number of Americans entrenched at Bemis Heights. After two battles, the Americans were victorious and General Burgoyne surrendered to the Americans, led by General Horatio Gates on October 17, 1777. The Battle of Saratoga became famously known as the turning point of the American Revolution. -

French & Indian War Bibliography 3.31.2017

BRITISH, FRENCH, AND INDIAN WAR BIBLIOGRAPHY Detre Library & Archives, Heinz History Center 1. ALL MATERIALS RELATED TO THE BRITISH, FRENCH AND INDIAN WAR (APPENDIX A not included) 2. FORTS/FORTIFICATIONS 3. BIOGRAPHY/AUTOBIOGRAPHY 4. DIARIES/PERSONAL NARRATIVES/LETTERS 5. SOLDIERS/ARMS/ARMAMENTS/UNIFORMS 6. INDIAN CAPTIVITIES 7. INDIAN HISTORY AND CULTURE 8. FRENCH AND INDIAN WAR HISTORIES 9. PONTIAC’S CONSPIRACY/LORD DUNMORE’S WAR 10. FICTION 11. ARCHIVAL APPENDIX A (Articles from the Western Pennsylvania Historical Magazine and Pittsburgh History) 1. ALL MATERIALS RELATED TO THE BRITISH, FRENCH AND INDIAN WAR A Brief History of Bedford Village; Bedford, Pa.; and Old Fort Bedford. • Bedford, Pa.: H. K. and E. K. Frear, 1961. • qF157 B25 B853 1961 A Brief History of the Colonial Wars in America from 1607 to 1775. • By Herbert T. Wade. New York: Society of Colonial Wars in the State of New York, 1948. • E186.3 N532 No. 51 A Brief History of the King’s Royal Rifle Corps. • Edited by Sir Edward T. H. Hutton. Winchester: Printed by Warren and Son, Ltd., 1912. • UA652 K5 H9 A Charming Field For An Encounter: The Story of George Washington’s Fort Necessity. • By Robert C. Alberts. National Park Service, 1975. • E199 A33 A Compleat History of the Late War: Or Annual Register of Its Rise, Progress, and Events in Europe, Asia, Africa and America. • Includes a narrative of the French and Indian War in America. Dublin: Printed by John Exshaw, M.DCC.LXIII. • Case dD297 C736 A Country Between: The Upper Ohio Valley and Its Peoples 1724-1774. -

1999 AS a SPECIAL SPATIAL YEAR for Pcbs in HUDSON RIVER FISH

1999 AS A SPECIAL SPATIAL YEAR FOR PCBs IN HUDSON RIVER FISH by Ronald J. Sloan, Michael W. Kane and Lawrence C. Skinner Bureau of Habitat, Division of Fish, Wildlife and Marine Resources New York State Department of Environmental Conservation Albany, New York May 31, 2002 TABLE OF CONTENTS Page ABSTRACT . ..............................................................1 INTRODUCTION ..........................................................3 METHODS AND PROCEDURES .............................................5 RESULTS AND DISCUSSION ...............................................8 The Collections ......................................................8 Laboratory Comparisons - ‘Aroclor’ versus Congeneric Methods ...............8 Influence of Age/Size/Sex/Lipid Content on PCB Concentration...............10 Age/Size versus PCB...........................................10 Sex Differences versus PCB .....................................11 Lipid Relationship.............................................12 Concentrations over the Spatial Gradient .................................13 Single Species Examples........................................13 Differences between Species.....................................14 Mid-Point Summary..................................................15 Basis for the ‘Species Smash’ ..........................................15 Source Conditions ...................................................16 Examination of the overall ANOVA ...............................16 Spatial Aspects Using Average Species Values.......................19 -

Trails Lead to New York State the Birth of Our Great Nation Started in New York State New York State: the Crossroads of History

® All Trails Lead To New York State The birth of our great nation started in New York State New York State: The Crossroads of History In colonial and revolutionary In the Battle of New York, Britain Map of the 13 Colonies 1775 MASS America, New York Sate nearly defeated George Washington was at the crossroads of the and the American Revolution, but growing nation and history. Washington rallied his battered army NH and set a standard for dedicated, self- That is because the men and women less public service that remains the NY who helped shape our modern world ideal of democracy everywhere. MASS came to New York and crossed paths: Sagarawithra, the chief of the A young African-American, James CON Tuscarora Indian Nation, led his Forten, came to New York as a Brit- RI people north to New York to join ish prisoner of war, and escaped to the Iroquois Confederacy, and safety, fight for the freedom and equality PA NJ peace and freedom. promised in the Declaration of In- dependence by founding the Ameri- Inspired by a visit to the Iroquois can Anti-Slavery Society. Margaret MD Confederacy, Benjamin Franklin Corbin came with her husband to DEL came to New York, the battleground New York, eager to serve, too, only to of the continent, to issue a call for a fall wounded in a desperate battle. VA colonial union to fight France, the first glimmer of the idea that became Those crossroads and crossed paths the United States. French General also brought great villains like Montcalm marched his army south Benedict Arnold, who gave his name into New York, only to predict in to treason and treachery. -

History of Fort Edward and Roger's Island

HISTORY OF FORT EDWARD AND ROGERS ISLAND The present village of Fort Edward, New York, was called “The Great Carrying Place” because it was the portage between the Hudson River and Lake Champlain. The first recorded military expedition to have passed through the Great Carrying Place, led by Major General Fitz-John Winthrop, occurred in 1690. The following year, Peter Schuyler led another expedition against Canada. The first fortification to have been built in Fort Edward was under the command of Colonel Francis Nicholson in 1709, during the conflict known as “Queen Anne’s War.” Fort Nicholson was garrisoned by 450 men, including seven companies of “regulars in scarlet uniform from old England.” A crude stockade was built to protect storehouses and log huts. John Henry Lydius, a Dutch fur trader, came to the site of Fort Nicholson to construct a trading post in 1731. Lydius claimed this land under a title granted to the Rev. Dellius in 1696. According to a 1732 French map, the trading post may have been surrounded by storehouses and fortified. Lydius may also have built a sawmill on Rogers Island. It is unknown whether the Lydius post was destroyed and later reconstructed in 1745 when many French and Indian raids were being conducted on the Hudson River. Many Provincial troops arrived at the Great Carrying Place during July and August of 1755. Among these were the celebrated Rogers’ Rangers. Rogers Island became the base camp for the Rangers for about 2 ½ years during the French and Indian War. Many Ranger huts, a blockhouse, a large barracks complex, and a large smallpox hospital were constructed on Rogers Island between 1756 and 1759. -

Reclaiming the Hudson River Brochure

Reclaiming the Hudson The Saratoga County Riverscape Project Reclaiming the Hudson The Saratoga County Riverscape Project The vision ivers define communities. The Hudson River is R With change comes opportunity. The no exception. This quintessential American river upcoming Hudson River dredging project conjures up images of the past as we recall the story of provides a chance to reevaluate the role Henry Hudson and his crew of the Half Moon and tales of the Hudson River in our communities. of Native Americans and early settlers who enjoyed the New projects will be initiated to create bounties of the upper Hudson River. For generations, exciting new public spaces, highlight the the Hudson River has been the backbone of many exceptional educational and recreational resources along the river, and spark Saratoga County communities. Together with the economic development opportunities Champlain Canal, completed in 1822, the river brought throughout the corridor. There are two great prosperity to the region through the 19th century. corridor projects that are a shared goal This waterway corridor links centuries of historic for all the communities: a continuous events, notable people, and landmarks that shaped our greenway trail from Waterford to Moreau nation. Today, the region attracts tourists interested in and the navigational dredging of the Champlain Canal. heritage tourism with interpretive attractions ranging The Riverscape Project is designed from the influential Native American era, through to illustrate the present and planned the American Revolution , to the importance of the initiatives along the Hudson River/ Industrial Revolution, and the construction of the Champlain Canal corridor and how Champlain Barge Canal. -

Cultural Resources Work Plan for the Hudson River Pcbs Superfund Site

WORK PLAN Cultural and Archaeological Resources Assessment Work Plan for the Hudson River PCBs Superfund Site General Electric Company Albany, New York August 2003 Corporation WORK PLAN TABLE OF CONTENTS 1.0 Introduction ......................................................................................................................... 1 1.1 Background ............................................................................................................. 2 Figure 1: Location Map........................................................................................... 3 1.2 The Regulatory Framework .................................................................................... 4 1.3 Previous Surveys..................................................................................................... 5 1.4 Scope ....................................................................................................................... 7 1.5 Overview of Work................................................................................................... 9 2.0 Methodology ..................................................................................................................... 10 2.1 Literature Review.................................................................................................. 10 2.2 Collection of Additional Field Data (Part of SSAP)............................................. 13 2.2.1 Geophysical Surveys........................................................................... 13 2.2.2 Sediment