Iraqi Force Development: Summer 2006 Update

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

† the Funeral of the Late Kathleen Kadir Will Take Place This Friday at 10

Catholic Church MASS INTENTIONS Sat 22 Nov 6.00pm Luke Wall (Anniversary) 60 Highbury Park Sun 23 Nov 9.00am Bianca Mansi (Anniversary) London N5 2XH 11.00am Levi Cronin & Pat Whitbread (RIP) T 020 7226 0257 Mon 24 Nov 9.15am The Holy Souls E [email protected] Tues 25 Nov 9.15am Carmela & Emile Krawcuz (RIP) Wed 26 Nov 9.15am The Holy Souls www.stjoanofarcparish.co.uk Thu 27 Nov 9.15am Francis Trapani (RIP) Parish Blog Fri 28 Nov 8.00am Margaret Gallagher (Intentions) www.stjoanofarcparishuk.wordpre Sat 29 Nov 10.00am The Holy Souls ss.com/ 6.00pm Michael McManus (Anniversary) Rev Gerard G King Sun 30 Nov 9.00am For You The People 11.00am Mary Harrington (Anniversary) Parish Priest Sunday, 23 November, 2014 NEWSLETTER Our Lord Jesus Christ, King of the Universe First Communion Catechists’ Meeting this Monday Pope Having Showers Built in Vatican Introductionfor Rome's evening at 7.30pm in the presbytery. Today we celebrateHomeless Christ T ashe ourVatican king. has We announced will learn about that the the Holy values Father of love andhas compassion commissioned in God’s three kingdom showers and to behow built Jesus for judgesuse by histhe Calling all “Facebook” users! When visiting “Facebook”, homeless in the area under the colonnades of followers.St. Peter’s please add “My Hospital Prayer and Activities Book” as a Square. The showers will be installed in an existing lavatory “like”, to aid its publicity. This unique and original Catholic block used by tourists and pilgrims. An experience of the publication aims to help children pray if their patients are in Pope’s almoner, Archbishop Konrad Krajewski,Penitential led to Act the hospital. -

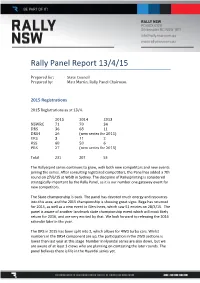

Rally Panel Report 13/4/15

Rally Panel Report 13/4/15 Prepared for: State Council Prepared by: Matt Martin, Rally Panel Chairman. 2015 Registrations 2015 Registrations as at 13/4. 2015 2014 2013 NSWRC 71 70 34 DRS 36 68 11 DRS4 26 (new series for 2015) ERS 3 11 2 RSS 68 58 6 PRS 27 (new series for 2015) Total 231 207 53 The Rallysrpint series continues to grow, with both new competitors and new events joining the series. After consulting registered competitors, the Panel has added a 7th round on 27/6/15 at WSID in Sydney. The discipline of Rallysprinting is considered strategically important by the Rally Panel, as it is our number one gateway event for new competitors. The State championship is back. The panel has devoted much energy and resources into this area, and the 2015 championship is showing great signs. Bega has returned for 2015, as well as a new event in Glen Innes, which saw 51 entries on 28/3/15. The panel is aware of another landmark state championship event which will most likely return for 2016, and are very excited by that. We look forward to releasing the 2016 calendar later in the year. The DRS in 2015 has been split into 2, which allows for 4WD turbo cars. Whilst numbers in the DRS4 component are up, the participation in the 2WD sections is lower than last year at this stage. Number in Hyundai series are also down, but we are aware of at least 3 crews who are planning on contesting the later rounds. -

Highlight Der Woche: Top Gear Eps. 1

DMAX Programm Programmwoche 36, 01.09. bis 07.09.2012 Highlight der Woche: Top Gear Eps. 1 (16) Am Montag, 10.09.2012 um 20:15 Uhr Wehe wenn sie losgelassen: In der neuen Staffel testen die Jungs von "Top Gear" die tollsten Luxuskarossen - manchmal geht´s jedoch auch mit dem Mähdrescher in den Schnee oder dem Hubschrauber aufs Autodach… Die spektakulärsten Autos der Welt, Testfahrten auf dem Vulkan und jede Menge coole Sprüche: DMAX holt "Top Gear" - die Mutter aller Auto-Shows - nach Hause. Das weltweit erfolgreichste TV-Format rund ums Thema „fahrbarer Untersatz“ begeistert seine Zuschauer seit Jahren mit sensationellen Stunts, präzise recherchierten Beiträgen und gefürchteten Kfz-Kritiken. Mehr Leidenschaft fürs Auto geht nicht! Darin ist sich die riesige Fan-Gemeinde des Kult-Formats rund um den Globus einig. Ganz zu schweigen vom bissigen britischen Humor der Moderatoren Jeremy Clarkson, Richard Hammond und James May. Die ironischen Kommentare der Auto-Experten sind eben nicht zu toppen. Kurzum: Top Gear ist Kult! Know-how, Enthusiasmus und Faszination - die preisgekrönte BBC-Produktion hat mit DMAX in Deutschland die perfekte Heimat gefunden. "Als würde die Queen einen Tanga unterm Rock tragen!" - die Vergleiche, die Jeremy Clarkson in dieser Episode zieht, grenzen an Majestätsbeleidung. Doch der Top Gear-Experte ist vom schicken Interieur des Jaguar XJ so begeistert, dass er etwas über die Stränge schlägt. Da die luxuriöse V8- Raubkatze außerdem mächtig Dampf unterm Kessel hat, macht es Jeremy einen Riesenspaß auf der britischen Insel von Küste zu Küste zu brettern. Weitere Highlights dieser Episode: Porsche 959 und Ferrari F40 im Vergleich, sowie ein 3,5 Millionen Euro teuer NASA-Mondbuggy. -

Top Gear Top Gear

Top Gear Top Gear The Canon C300, Sony PMW-F55, Sony NEX-FS700 capable of speeds of up to 40mph, this was to and ARRI ALEXA have all complemented the kit lists be as tough on the camera mounts as it no doubt on recent shoots. As you can imagine, in remote was on Clarkson’s rear. The closing shot, in true destinations, it’s essential to have everything you need Top Gear style, was of the warning sticker on Robust, reliable at all times. A vital addition on all Top Gear kit lists is a the Gibbs machine: “Normal swimwear does not and easy to use, good selection of harnesses and clamps as often the adequately protect against forceful water entry only suitable place to shoot from is the roof of a car, into rectum or vagina” – perhaps little wonder the Sony F800 is or maybe a dolly track will need to be laid across rocks then that the GoPro mounted on the handlebars the perfect tool next to a scarily fast river. Whatever the conditions was last seen sinking slowly to the bottom of the for filming on and available space, the crew has to come up with a lake! anything from solution while not jeopardising life, limb or kit. As one In fact, water proved to be a regular challenge car boots and of the camera team says: “We’re all about trying to stay on Series 21, with the next stop on the tour a one step ahead of the game... it’s just that often we wet Circuit de Spa-Francorchamps in Belgium, roofs to onboard don’t know what that game is going to be!” where Clarkson would drive the McLaren P1. -

The Clarkson Controversy: the Impact of a Freewheeling Presenter on The

The Clarkson Controversy: the Impact of a Freewheeling Presenter on the BBC’s Impartiality, Accountability and Integrity BA Thesis English Language and Culture, Utrecht University International Anglophone Media Studies Laura Kaai 3617602 Simon Cook January 2013 7,771 Words 2 Table of Contents 1. Introduction 3 2. Theoretical Framework 4 2.1 The BBC’s Values 4 2.1.2 Impartiality 5 2.1.3 Conflicts of Interest 5 2.1.4 Past Controversy: The Russell Brand Show and the Carol Thatcher Row 6 2.1.5 The Clarkson Controversy 7 2.2 Columns 10 2.3 Media Discourse Analysis 12 2.3.2 Agenda Setting, Decoding, Fairness and Fallacy 13 2.3.3 Bias and Defamation 14 2.3.4 Myth and Stereotype 14 2.3.5 Sensationalism 14 3. Methodology 15 3.1 Columns by Jeremy Clarkson 15 3.1.2 Procedure 16 3.2 Columns about Jeremy Clarkson 17 3.2.2 Procedure 19 4. Discussion 21 4.1 Columns by Jeremy Clarkson 21 4.2 Columns about Jeremy Clarkson 23 5. Conclusion 26 Works Cited 29 Appendices 35 3 1. Introduction “I’d have them all shot in front of their families” (“Jeremy Clarkson One”). This is part of the comment Jeremy Clarkson made on the 2011 public sector strikes in the UK, and the part that led to the BBC receiving 32,000 complaints. Clarkson said this during the 30 December 2011 live episode of The One Show, causing one of the biggest BBC controversies. The most widely watched factual TV programme in the world, with audiences in 212 territories worldwide, is BBC’s Top Gear (TopGear.com). -

INTRODUCING the TOP GEAR LIMITED EDITION BUGG BBQ from BEEFEATER Searing Performance for the Meat Obsessed Motorist

PRESS RELEASE INTRODUCING THE TOP GEAR LIMITED EDITION BUGG BBQ FROM BEEFEATER Searing Performance for the Meat Obsessed Motorist “It’s Flipping Brilliant” Sydney, Australia, 19 November 2012 BeefEater, the Australian leaders in barbecue technology, has partnered with BBC Worldwide Australasia to create an innovative and compact Top Gear Limited Edition BUGG® (BeefEater Universal Gas Grill) BBQ, that will make you the envy of your mates. The Limited Edition BBQ from BeefEater comes with an exclusive Top Gear accessory bundle which includes a Stig oven mitt and apron to help you look the part while cooking. It also features a bespoke Top Gear gauge and tyre‐track temperature control knob to keep you on track whilst perfecting your meat. ‘Top Gear’s Guide on How Not to BBQ’ is also included, with helpful tips such as ‘do not attempt to modify your barbecue by fitting an aftermarket exhaust’ and ‘this barbecue is not suitable for children, or adults who behave like children’ guiding users through those trickier BBQ moments. The BBQ launches in Australia just in time for Christmas at Harvey Norman and other leading independent retailers, and will be available in the UK and Europe when the weather’s a little better. “A cool white hood, precision controls, bespoke gauges and a high performance ignition – what a way to convince the meat obsessed motorist to get out of the garage and cook dinner! This new Top Gear Limited Edition BUGG BBQ from BeefEater is a high performance vehicle, making cooking ability an optional extra,” says Elie Mansour, BBC Worldwide Australasia’s Manager Licensed Consumer Products. -

Investigation Into the the Accident of Richard Hammond

Investigation into the accident of Richard Hammond Accident involving RICHARD HAMMOND (RH) On 20 SEPTEMBER 2006 At Elvington Airfield, Halifax Way, Elvington YO41 4AU SUMMARY 1. The BBC Top Gear programme production team had arranged for Richard Hammond (RH) to drive Primetime Land Speed Engineering’s Vampire jet car at Elvington Airfield, near York, on Wednesday 20th September 2006. Vampire, driven by Colin Fallows (CF), was the current holder of the Outright British Land Speed record at 300.3 mph. 2. Runs were to be carried out in only one direction along a pre-set course on the Elvington runway. Vampire’s speed was to be recorded using GPS satellite telemetry. The intention was to record the maximum speed, not to measure an average speed over a measured course, and for RH to describe how it felt. 3. During the Wednesday morning RH was instructed how to drive Vampire by Primetime’s principals, Mark Newby (MN) and CF. Starting at about 1 p.m., he completed a series of 6 runs with increasing jet power and at increasing speed. The jet afterburner was used on runs 4 to 6, but runs 4 and 5 were intentionally aborted early. 4. The 6th run took place at just before 5 p.m. and a maximum speed of 314 mph was achieved. This speed was not disclosed to RH. 5. Although the shoot was scheduled to end at 5 p.m., it was decided to apply for an extension to 5:30 p.m. to allow for one final run to secure more TV footage of Vampire running with the after burner lit. -

Sanford Bernstein's 9Th Annual Strategic Decisions

André Lacroix Group Chief Executive Distributor and retailer for the world’s leading automotive brands Right Markets: Right Categories: 2/3 revenues Five distinct from Asia Pacific revenue streams & Emerging offering growth / Markets defensive mix Right Brands: Right Financials: 90% of profits Attractive growth from 6 leading prospects, strong premium cash generation & OEMs robust balance sheet Distinct and attractive business model in the automotive sector 3 4 Majority of global growth in population and GDP will come from Asia Pacific and Emerging Markets Western Europe Eastern Europe & Russia North America GDP 2012: $16,847bn GDP 2012: $4,870bn GDP 2012: $17,414bn Growth 2012-17: + $2,708bn Growth 2012-17: + $2,292bn Growth 2012-17: + $4,431bn Pop 2012: 413m Pop 2012: 449m Pop 2012: 350m Growth 2012-17: + 7m Growth 2012-17: + 1m Growth 2012-17: + 17m Middle East GDP 2012: $2,559 bn Growth 2012-17: + $616bn Pop 2012: 231m Growth 2012-17: + 26m Africa Asia & Oceania South & Central America GDP 2012: $2,069bn GDP 2012: $22,350bn GDP 2012: $5,788bn Growth 2012-17: + $777bn Growth 2012-17: + $9,497bn Growth 2012-17: + $1,811bn Pop 2012: 1,060m Pop 2012: 3,858m Pop 2012: 584m Growth 2012-17: + 132m Growth 2012-17: + 199m Growth 2012-17: + 35m Source: IMF (nominal GDP, population) Updated Sept 2012 Asia Pacific and Emerging Markets will represent 94% of population growth 2012 – 17 and 71% of GDP growth 5 …this pattern is reflected in car industry growth Western Europe Eastern Europe & Russia North America TIV 2012 13.2m TIV 2012 5.1m TIV 2012 -

Approved Movie List 10-9-12

APPROVED NSH MOVIE SCREENING COMMITTEE R-RATED and NON-RATED MOVIE LIST Updated October 9, 2012 (Newly added films are in the shaded rows at the top of the list beginning on page 1.) Film Title ALEXANDER THE GREAT (1968) ANCHORMAN (2004) APACHES (also named APACHEN)(1973) BULLITT (1968) CABARET (1972) CARNAGE (2011) CINCINNATI KID, THE (1965) COPS CRUDE IMPACT (2006) DAVE CHAPPEL SHOW (2003–2006) DICK CAVETT SHOW (1968–1972) DUMB AND DUMBER (1994) EAST OF EDEN (1965) ELIZABETH (1998) ERIN BROCOVICH (2000) FISH CALLED WANDA (1988) GALACTICA 1980 GYPSY (1962) HIGH SCHOOL SPORTS FOCUS (1999-2007) HIP HOP AWARDS 2007 IN THE LOOP (2009) INSIDE DAISY CLOVER (1965) IRAQ FOR SALE: THE WAR PROFITEERS (2006) JEEVES & WOOSTER (British TV Series) JERRY SPRINGER SHOW (not Too Hot for TV) MAN WHO SHOT LIBERTY VALANCE, THE (1962) MATA HARI (1931) MILK (2008) NBA PLAYOFFS (ESPN)(2009) NIAGARA MOTEL (2006) ON THE ROAD WITH CHARLES KURALT PECKER (1998) PRODUCERS, THE (1968) QUIET MAN, THE (1952) REAL GHOST STORIES (Documentary) RICK STEVES TRAVEL SHOW (PBS) SEX AND THE SINGLE GIRL (1964) SITTING BULL (1954) SMALLEST SHOW ON EARTH, THE (1957) SPLENDER IN THE GRASS APPROVED NSH MOVIE SCREENING COMMITTEE R-RATED and NON-RATED MOVIE LIST Updated October 9, 2012 (Newly added films are in the shaded rows at the top of the list beginning on page 1.) Film Title TAMING OF THE SHREW (1967) TIME OF FAVOR (2000) TOLL BOOTH, THE (2004) TOMORROW SHOW w/ Tom Snyder TOP GEAR (BBC TV show) TOP GEAR (TV Series) UNCOVERED: THE WAR ON IRAQ (2004) VAMPIRE SECRETS (History -

Top Gear and Anti-Environmentalism AS Jan16.Pdf

Drake, Philip and Smith, Angela (2016) Belligerent broadcasting, male antiauthoritarianism and anti- environmentalism: the case of Top Gear (BBC, 2002–2015). Environmental Communication, 10 (6). pp. 689-703. ISSN 1752- 4 0 3 2 Downloaded from: http://sure.sunderland.ac.uk/id/eprint/6668/ Usage guidelines Please refer to the usage guidelines at http://sure.sunderland.ac.uk/policies.html or alternatively contact [email protected]. Please note, this article was submitted before the presenting team of Top Formatted: Left Gear were dismissed by the BBC. The published article, that considers Formatted: Font: Italic these changes, can be found here: http://www.tandfonline.com/doi/full/10.1080/17524032.2016.1211161 Belligerent broadcasting, male anti-authoritarianism and anti- environmentalism: the case of Top Gear (BBC, 2002-) Philip Drake and Angela Smith Abstract This article considers the format and cultural politics of the hugely successful UK TV programme Top Gear (BBC 2002-) analysing how it constructs an informal address predicated around anti-authoritarian or contrarian banter and protest masculinity. Regular targets for Top Gear presenter's protest – which are curtailed by broadcast guidelines in terms of gender and ethnicity -- are reflected in the 'soft' targets of government legislation on environmental issues or various forms of regulation ‘red tape’. Repeated references to speed cameras, central London congestion charges, and 'excessive' signage, are all anti-authoritarian, libertarian discourses delivered through a comedic form of performance address. Thus the BBC's primary response to complaints made about this programme is to defend the programme's political views as being part of the humour. -

The Top Gear Guide to Britain: a Celebration of the Fourth Best Country in the World Free Download

THE TOP GEAR GUIDE TO BRITAIN: A CELEBRATION OF THE FOURTH BEST COUNTRY IN THE WORLD FREE DOWNLOAD Richard Porter | 160 pages | 01 May 2014 | Ebury Publishing | 9781849906906 | English | London, United Kingdom How Spring's Arrival Is Celebrated Around the World By Ben Schiller 2 minute Read. It also considers environmental factors like clean water access and sanitation. Here are the fastest ones you can buy in Britain right now. Sir Steve Redgrave. Rowan Horncastle. Views Read Edit View history. Share Twitter Pinterest Email. Clarkson, Hammond and May visit all four corners of the globe, as the trio herd cows in the far reaches of Australia and conduct a half-hearted search and rescue operation in the wilderness of British Columbia. Airport vehicle motorsport. A look back at some of the best moments from Series 13 and 14, including the race between the Bugatti Veyron and the Mclaren F1, and the trio's s race between the car, bike and train. Elsewhere, Clarkson reviews Audi's first supercar, the Audi R8before competing in a drag race when Hammond arrives with a Porsche Carrera Swhile Jools Holland sees if he can make lap time music in the Lacetti. Mike Channell. The last vestiges of the Cold War seemed to thaw for a moment on Feb. Formerly 71United Arab Republic. The presenters take on a raft of engineering challenges as they build a convertible people carrier out of a Renault Espace, make three amphibious cars The Top Gear Guide to Britain: A Celebration of the Fourth Best Country in the World attempt to construct a Caterham Seven faster than the Stig can drive from Surrey to Scotland in a ready-made version of the same vehicle. -

Costs and Charges: Regulators Move Into Top Gear

Costs and charges: regulators move into top gear Evolving Investment Management Regulation 2017 KPMG International kpmg.com 1 Evolving Investment Management Regulation: Succeeding in an uncertain landscape This article forms part of the Evolving Investment Management Regulation report, available at: kpmg.com/eimr Driven by political, regulator, investor and media attention, costs and charges now sit squarely at the top of the reform agenda in the investment and fund management industry. If there was any doubt about the importance of the issue, recent moves by IOSCO and ESMA have removed it. Within Europe, the implementation of MiFID II will bring about fundamental changes to industry commission practices, and a number of other countries, too, have introduced new rules in this area. A number of regulators continue to scrutinize the level of charges and their disclosure. “Closet tracking” remains under the spotlight and the UK, for example, is applying more intensive scrutiny to the level of charges for “active” fund management. Disclosure of the remuneration of senior management and portfolio managers continues to attract regulatory attention. © 2017 KPMG International Cooperative (“KPMG International”), a Swiss entity. Member firms of the KPMG network of independent firms are affiliated with KPMG International. KPMG International provides no client services. No member firm has any authority to obligate or bind KPMG International or any other member firm vis-à-vis third parties, nor does KPMG International have any such authority to obligate or bind any member firm. All rights reserved. Evolving Investment Management Regulation: Succeeding in an uncertain landscape 2 transaction. There is less agreement IOSCO guidance on whether implicit costs can be likely to be seen measured retrospectively.