Cont Pp I-Iv Vol.21 2009 B.PUB

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

4. Shakespeare Authorship Doubt in 1593

54 4. Shakespeare Authorship Doubt in 1593 Around the time of Marlowe’s apparent death, the name William Shakespeare appeared in print for the first time, attached to a new work, Venus and Adonis, described by its author as ‘the first heir of my invention’. The poem was registered anonymously on 18 April 1593, and though we do not know exactly when it was published, and it may have been available earlier, the first recorded sale was 12 June. Scholars have long noted significant similarities between this poem and Marlowe’s Hero and Leander; Katherine Duncan-Jones and H.R. Woudhuysen describe ‘compelling links between the two poems’ (Duncan-Jones and Woudhuysen, 2007: 21), though they admit it is difficult to know how Shakespeare would have seen Marlowe’s poem in manuscript, if it was, as is widely believed, being written at Thomas Walsingham’s Scadbury estate in Kent in the same month that Venus was registered in London. The poem is preceded by two lines from Ovid’s Amores, which at the time of publication was available only in Latin. The earliest surviving English translation was Marlowe’s, and it was not published much before 1599. Duncan-Jones and Woudhuysen admit, ‘We don’t know how Shakespeare encountered Amores’ and again speculate that he could have seen Marlowe’s translations in manuscript. Barber, R, (2010), Writing Marlowe As Writing Shakespeare: Exploring Biographical Fictions DPhil Thesis, University of Sussex. Downloaded from www. rosbarber.com/research. 55 Ovid’s poem is addressed Ad Invidos: ‘to those who hate him’. If the title of the epigram poem is relevant, it is more relevant to Marlowe than to Shakespeare: personal attacks on Marlowe in 1593 are legion, and include the allegations in Richard Baines’ ‘Note’ and Thomas Drury’s ‘Remembrances’, Kyd’s letters to Sir John Puckering, and allusions to Marlowe’s works in the Dutch Church Libel. -

The Printers of Shakespeare's Plays and Poems

149 Downloaded from https://academic.oup.com/library/article/s2-VII/26/149/943715 by guest on 27 September 2021 THE PRINTERS OF SHAKESPEARE'S PLAYS AND POEMS. HE men who, during Shakespeare's lifetime, printed his * Venus and Ado- nis,' * Lucrece,' and * Sonnets,' and the Quarto editions of his plays, can hardly be called Shakespeare's printers, since, with one exception, there is no evidence that he ever authorized the printing of any of his works, or ever revised those that were published. Even in the case of Richard Field, the evidence is presumptive and not direct. Yet Englishmen may be pardoned if they cling to the belief that Shakespeare employed Field to print for him and frequented the printing office in Blackfriars while the proof sheets of * Venus and Adonis' and ' Lucrece' were passing through the press. For Stratford-on-Avon claimed both the printer and the poet, and if it be a stretch of the imagination to look upon them as fellow scholars in the grammar school, and playmates in the fields, their distant Warwickshire birthplace offered a bond of sympathy which might well draw them to one another. It is some matter for congratulation that the first of Shakespeare's writings to be printed came from a press that had long been known for the excellence of its work. When Richard Field came to London in 1579, be entered the service of a bookseller, but 150 PRINTERS OF SHAKESPEARE'S within a year he was transferred, probably at his own desire, to the printing office of Thomas Vau- trollicr, the Huguenot printer in Blackfriars. -

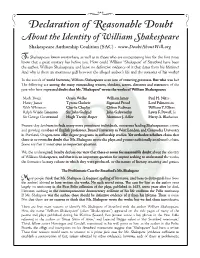

SAC Declaration of Reasonable Doubt

Shakespeare Authorship Coalition (SAC) - www.DoubtAboutWill.org To Shakespeare lovers everywhere, as well as to those who are encountering him for the first time: know that a great mystery lies before you. How could William “Shakspere” of Stratford have been the author, William Shakespeare, and leave no definitive evidence of it that dates from his lifetime? And why is there an enormous gulf between the alleged author’s life and the contents of his works? In the annals of world literature, William Shakespeare is an icon of towering greatness. But who was he? past who have expressed doubt that Mr. “Shakspere” wrote the works of William Shakespeare: Mark Twain Orson Welles William James Paul H. Nitze Henry James 5ZSPOF(VUISJF Sigmund Freud Lord Palmerston Walt Whitman $IBSMJF$IBQMJO Clifton Fadiman William Y. Elliott 3BMQI8BMEP&NFSTPO 4JS+PIO(JFMHVE John Galsworthy Lewis F. Powell, Jr. 4JS(FPSHF(SFFOXPPE )VHI5SFWPS3PQFS Mortimer J. Adler Harry A. Blackmun Present-day doubters include many more prominent individuals, numerous leading Shakespearean actors, and growing numbers of English professors. Brunel University in West London, and Concordia University in Portland, Oregon, now offer degree programs in authorship studies. Yet orthodox scholars claim that there is no room for doubt that Mr. Shakspere wrote the plays and poems traditionally attributed to him. Some say that it is not even an important question. We, the undersigned, hereby declare our view that there is room for reasonable doubt about the identity of William Shakespeare, and that it is an important question for anyone seeking to understand the works, the formative literary culture in which they were produced, or the nature of literary creativity and genius. -

Redalyc.Cymbeline: Arithmetic, Double-Entry Bookkeeping, Counts, and Accounts

SEDERI Yearbook ISSN: 1135-7789 [email protected] Spanish and Portuguese Society for English Renaissance Studies España Parker, Patricia Cymbeline: Arithmetic, Double-Entry Bookkeeping, Counts, and Accounts SEDERI Yearbook, núm. 23, 2013, pp. 95-119 Spanish and Portuguese Society for English Renaissance Studies Valladolid, España Available in: http://www.redalyc.org/articulo.oa?id=333538759005 How to cite Complete issue Scientific Information System More information about this article Network of Scientific Journals from Latin America, the Caribbean, Spain and Portugal Journal's homepage in redalyc.org Non-profit academic project, developed under the open access initiative Cymbeline: Arithmetic, Double-Entry Bookkeeping, Counts, and Accounts Patricia Parker Stanlord University ABSTRAeT The importance of cornmercial arithmetic and double-entry bookkeeping (or l/debitar and creditor" accounting) has been traced in The Merchl1nt DI Venice, Othello, the Sonnets, and other works of Shakespeare and rus contemporaries. But even though both are explicitly cited in Cymbeline (the only Shakespeare play other than Othello to invoke double-entry by its contemporary English name), their importance for this late Shakespearean tragicomic romance has yet to be explored. This article traces multiple ways in which Cymbeline i5 impacted by arithmetic and the arts of calculation, risk-taking, surveying, and measuring; its pervasive language of credit, usury, gambling, and debt, as well as slander infidelity and accounting counterfeiting; the contemporary cont1ation of the female /la" with arithmetic's zero or /lcipher// in relation to alleged infidelity; and the larger problem of trust (fram credere and credo) that is crucial to this play as well as to early modern England's culture of credit. -

Final Copy 2019 01 23 Wilkin

This electronic thesis or dissertation has been downloaded from Explore Bristol Research, http://research-information.bristol.ac.uk Author: Wilkins, Vernon Title: A Field the Lord hath Blessed the Person, Works, Life and Polemical Ecclesiology of Richard Field, DD, 15611616 General rights Access to the thesis is subject to the Creative Commons Attribution - NonCommercial-No Derivatives 4.0 International Public License. A copy of this may be found at https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/legalcode This license sets out your rights and the restrictions that apply to your access to the thesis so it is important you read this before proceeding. Take down policy Some pages of this thesis may have been removed for copyright restrictions prior to having it been deposited in Explore Bristol Research. However, if you have discovered material within the thesis that you consider to be unlawful e.g. breaches of copyright (either yours or that of a third party) or any other law, including but not limited to those relating to patent, trademark, confidentiality, data protection, obscenity, defamation, libel, then please contact [email protected] and include the following information in your message: •Your contact details •Bibliographic details for the item, including a URL •An outline nature of the complaint Your claim will be investigated and, where appropriate, the item in question will be removed from public view as soon as possible. “A Field the Lord hath Blessed” The Person, Works, Life and Polemical Ecclesiology of -

Shakespeare Editions and Editors

Shakespeare Editions and Editors The 16th and 17th Centuries The earliest texts of William Shakespeare’s works were published during the sixteenth and seventeenth centuries in quarto or folio format. Folios are large, tall volumes; quartos are smaller, roughly half the size. Early Texts of Shakespeare’s Works: The Quartos and Bad Quartos (1594-1623) Of the thirty-six plays contained in the First Folio of 1623, eighteen have no other source. The eighteen other plays had been printed in separate and individual editions at least once between 1594 and 1623. Pericles (1609) and The Two Noble Kinsmen (1634) also appeared separately before their inclusions in folio collections. All of these were quarto editions, with one exception: the first edition of Henry VI, Part 3 was printed in octavo form in 1594. Popular plays like Henry IV, Part 1 and Pericles were reprinted in their quarto editions even after the First Folio appeared, sometimes more than once. But since the prefatory matter in the First Folio itself warns against the earlier texts, 18th and 19th century editors of Shakespeare tended to ignore the quarto texts in favor of the Folio. Gradually, however, it was recognized that the quarto texts varied widely among themselves; some much better than others. It was the bibliographer Alfred W. Pollard who originated the term “bad quarto” in 1909, to distinguish several texts that he judged significantly corrupt. He focused on four early quartos: Romeo and Juliet (1597), Henry V (1600), The Merry Wives of Windsor (1602), and Hamlet (1603). His reasons for citing these texts as “bad” were that they featured obvious errors, changes in word order, gaps in the sense of the text, jumbled printing of prose as verse and verse as prose, and similar problems. -

04 Woudhuysen 1226 7/12/04 12:01 Pm Page 69

04 Woudhuysen 1226 7/12/04 12:01 pm Page 69 SHAKESPEARE LECTURE The Foundations of Shakespeare’s Text H. R. WOUDHUYSEN University College London EIGHTY YEARS AGO TODAY my great-grandfather, Alfred W. Pollard, delivered this Annual Shakespeare Lecture on ‘The Foundations of Shakespeare’s Text’, the lecture coinciding with the tercentenary of the publication of the First Folio. To compare great things to small, this year all we can celebrate is the quatercentenary of the first quarto of Hamlet— a so-called ‘bad’ quarto. Surveying current knowledge about the quarto and Folio editions of Shakespeare’s plays, Pollard argued that, compared to the fate of Dr Faustus (‘a few fine speeches overladen with much alien buffoonery’) or the texts of the plays of Greene and Peele (‘scanty and mangled’), Shakespeare’s plays ‘have come down to us in so much better condition’, the texts presenting ‘to the sympathetic reader, and still more to the sympathetic listener . very few obstacles’. No wonder he called himself ‘an incurable optimist’—a characteristic I have not fully inherited from him.1 That general optimism about the state of Shakespeare’s texts was largely shared by Pollard’s friends and followers R. B. McKerrow and W. W. Greg, the proponents of what became known as the ‘New Bibliography’. The three of them elaborated an essential model of textual transmission, involving two sorts of lost manuscript—autograph drafts (called in con- temporary documents ‘foul papers’) and the theatrical ‘promptbook’— and two types of quarto. There were ‘bad’ quartos, containing shorter, Read at the Academy 23 April 2003. -

Reclaiming the Passionate Pilgrim for Shakespeare

Reclaiming The Passionate Pilgrim for Shakespeare Katherine Chiljan he Passionate Pilgrim (1598-1599) is a hornet’s nest of problems for academic Shakespeareans. This small volume is a collection of twenty T poems with the name “W. Shakespeare” on the title page. Only fragments of the first edition survive; its date is reckoned as late 1598 or 1599, the same year as the second edition. Scholars agree that the text was pirated. Why it was called The Passionate Pilgrim is unknown. It has been suggested that the title was publisher William Jaggard’s at- tempt to fulfill public demand for Shake- speare’s “sugar’d sonnets circulated among his private friends” that Francis Meres had recently mentioned in Palladis Tamia, or Wit’s Treasury , also published 1598. Jag- gard somehow acquired two Shakespeare sonnets (slightly different versions of 138 and 144 in Thomas Thorpe’s 1609 edition), and placed them as the first and second poems in his collection. Three additional pieces (3, 5 and 16) were excerpts from Act IV of Love’s Labor’s Lost , which was also printed in 1598. A total of five poems, therefore, were unquestionably by Shakespeare. But attribution to Shakespeare for the rest has become confused and doubted because of the inclusion of pieces supposedly by other poets. Numbers 8 and 20 were published in Richard Barnfield’s The Encomion of Lady Pecunia: or The Praise of Money (1598); No. 11 appeared in Bartholomew Griffin’s Fidessa (1596); and No. 19, “Live with Me and Be My Love,” was later attributed to Christopher Marlowe. -

View Fast Facts

FAST FACTS Author's Works and Themes: Hamlet “Author's Works and Themes: Hamlet.” Gale, 2019, www.gale.com. Writings by William Shakespeare Play Productions • Henry VI, part 1, London, unknown theater (perhaps by a branch of the Queen's Men), circa 1589-1592. • Henry VI, part 2, London, unknown theater (perhaps by a branch of the Queen's Men), circa 1590-1592. • Henry VI, part 3, London, unknown theater (perhaps by a branch of the Queen's Men), circa 1590-1592. • Richard III, London, unknown theater (perhaps by a branch of the Queen's Men), circa 1591-1592. • The Comedy of Errors, London, unknown theater (probably by Lord Strange's Men), circa 1592-1594; London, Gray's Inn, 28 December 1594. • Titus Andronicus, London, Rose or Newington Butts theater, 24 January 1594. • The Taming of the Shrew, London, Newington Butts theater, 11 June 1594. • The Two Gentlemen of Verona, London, Newington Butts theater or the Theatre, 1594. • Love's Labor's Lost, perhaps at the country house of a great lord, such as the Earl of Southampton, circa 1594-1595; London, at Court, Christmas 1597. • Sir Thomas More, probably by Anthony Munday, revised by Thomas Dekker, Henry Chettle, Shakespeare, and possibly Thomas Heywood, evidently never produced, circa 1594-1595. • King John, London, the Theatre, circa 1594-1596. • Richard II, London, the Theatre, circa 1595. • Romeo and Juliet, London, the Theatre, circa 1595-1596. • A Midsummer Night's Dream, London, the Theatre, circa 1595-1596. • The Merchant of Venice, London, the Theatre, circa 1596-1597. • Henry IV, part 1, London, the Theatre, circa 1596-1597. -

From 1604 Shakespeare Lodged in Silver Street

The Tudors and Stuarts Thomas Vautrollier arrived in England from Troyes in 1562 and established one of the greatest printing houses of the Elizabethan age. He made vital contributions to the intellectual culture of Elizabethan England by producing some of the most important works on education, and key translations of the protestant theologians Martin Luther and Jean Calvin. He was one of the first to print music in England. At a time when English spelling was still chaotic, Vautrollier’s publication of Richard Mulcaster’s Elementarie offered a standardised spelling for 8,000 words, helping to stabilise the language. Shakespeare’s prose poems Venus and Adonis and The Rape of Lucrece were published in Vautrollier’s workshop by his apprentice and eventual successor Richard Field. They were dedicated to the 21 year old, handsome and charismatic Earl of Southampton, the object of the Bard’s further poetic adoration in the sonnets. The original stories were drawn from Ovid’s Metamorphoses, also published by Vautrollier. Shakespeare refers with sympathy to the plight of the Huguenots in Sir Thomas More, a co-authored play involving immigration and civil disobedience: © Bodleian Library “Imagine that you see the wretched strangers, Their babies at their backs and their poor luggage, Plodding to th’ ports and costs for transportation.” © Cobbe Collection, Hatchlands Park. John de Critz the Elder (attr), Portrait of Henry Wriotheseley, 3rd Earl of Southampton, c. 1590. From 1604 Shakespeare lodged in Silver Street, Cripplegate with the Mountjoys, a Huguenot family of tiremakers (ladies’ ornamental headgear), who had fled Picardy in the early 1580s. -

Gertrude's Power Position in Hamlet

POIS’NED ALE: GERTRUDE’S POWER POSITION IN HAMLET by Erin Elizabeth Lehmann A thesis submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts in English, Literature Boise State University May 2013 © 2013 Erin Elizabeth Lehmann ALL RIGHTS RESERVED BOISE STATE UNIVERSITY GRADUATE COLLEGE DEFENSE COMMITTEE AND FINAL READING APPROVALS of the thesis submitted by Erin Elizabeth Lehmann Thesis Title: Pois’ned Ale: Gertrude’s Power Position in Hamlet Date of Final Oral Examination: 19 March 2013 The following individuals read and discussed the thesis submitted by student Erin Elizabeth Lehmann, and they evaluated her presentation and response to questions during the final oral examination. They found that the student passed the final oral examination. Matthew C. Hansen, Ph.D. Chair, Supervisory Committee Linda Marie Zaerr, Ph.D. Member, Supervisory Committee Edward Mac Test, Ph.D. Member, Supervisory Committee Lisa McClain, Ph.D. Member, Supervisory Committee The final reading approval of the thesis was granted by Matthew C. Hansen, Ph.D., Chair of the Supervisory Committee. The thesis was approved for the Graduate College by John R. Pelton, Ph.D., Dean of the Graduate College. ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS I sincerely thank my thesis advisor, Dr. Matthew Hansen, and committee members, Dr. Linda Marie Zaerr, Dr. Lisa McClain, and Dr. Mac Test for their invaluable guidance and encouragement. iv ABSTRACT Hamlet has over 4,000 lines, and Gertrude speaks less than 200 of those lines (about 4% of the entire play), but her roles as a widow, wife, and mother drive much of the play’s action. This document brings together scholarship surrounding Gertrude’s roles within the play and new research into the historical cultural milieu of early modern England focused on working women to learn more about the cultural patterns influencing the creation of this character. -

The Printed Lute Song: a Textual and Paratextual Study of Early Modern English Song Books

The Printed Lute Song: A Textual and Paratextual Study of Early Modern English Song Books Michelle Lynn Oswell A dissertation submitted to the faculty of the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in the Department of Music Chapel Hill 2009 Approved by: John Nádas Timothy Carter James Haar Anne MacNeil Severine Neff © 2009 Michelle Lynn Oswell All Rights Reserved ii Abstract Michelle Lynn Oswell: The Printed Lute Song: A Textual and Paratextual Study of Early Modern English Song Books (Under the direction of John Nádas) The English lute song book of the late sixteenth and early seventeenth centuries represents a short-lived but well-admired flowering of English printed music. Situated between the birth of music printing in Italy at the turn of the sixteenth century and the rise of music printer John Playford in England in the 1650s, the printed lute song book’s style quite closely resembles the poetic miscellanies of the time. They were printed in folio and table book format rather than quarto-sized and in part books, their title pages often used elaborately-carved borders, and their prefatory material included letters rich with symbolism. Basing my work on the analyses of paratexts done by Gérard Genette and Michael Saenger, I examine the English printed lute song book from 1597-1622 as a book in and of itself. While there has been a fair amount of research done on the lute song as a genre and on some individual composers, which I discuss in the introduction, comparably little discussion of the books’ paratexts exists.