Download the Entire Heiller at Harvard CD Booklet (PDF)

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

May 19 Nat.Pdf

PIPEDREAMS Programs, May 2019 Spring Quarter: The following listings detail complete contents for the May 2019 Spring Quarter of broadcasts of PIPEDREAMS. The first section includes complete program contents, with repertoire, artist, and recording information. Following that is program information in "short form". For more information, contact your American Public Media station relations representative at 651-290-1225/877- 276-8400 or the PIPEDREAMS Office (651-290-1539), Michael Barone <[email protected]>). For last-minute program changes, watch DACS feeds from APM and check listing details on our PIPEDREAMS website: http://www.pipedreams.org AN IMPORTANT NOTE: It would be prudent to keep a copy of this material on hand, so that you, at the local station level, can field listener queries concerning details of individual program contents. That also keeps YOU in contact with your listeners, and minimizes the traffic at my end. However, whenever in doubt, forward calls to me (Barone). * * * * * * * PIPEDREAMS Program No. 1918 (distribution on 5/6/2019) On Stage . concert and competition performances feature ‘live’ music made vivid in the moment. [Hour 1] PAUL MANZ: Praise to the Lord, the Almighty. MARIUS MONNIKENDAM: Toccata. GUILLAUME DUFAY: Alma redemptoris mater. PIETER CORNET: Fantasy on the 8th Tone. J.-B. LOEILLET: Aria. FRANZ SCHMIDT: 2 Chorale-preludes (O Ewigkeit, du Donnerwort; Nun danket alle Gott) –John Schwandt (1966 Schlidker/Mount Olive Lutheran Church, Minneapolis, MN) PD Archive (r. 10/2/16). This repertoire was played by Paul Manz during the inaugural concert on this instrument fifty years ago. McNEIL ROBINSON: Soave e delicato, fr Sonata (1990). -

The Diapason an International Monthly Devoted to the Organ and the Interests of Organists

THE DIAPASON AN INTERNATIONAL MONTHLY DEVOTED TO THE ORGAN AND THE INTERESTS OF ORGANISTS Sixty-fourth Year~ No. 7 - Whole No. 763 J UNE. 19i3 Subscriptions .$4.00 a year - 40 cents a copy UNION SEMINARY SCHOOL OF METHODIST MUSICIANS SACRED MUSIC CONCLUDES TO MEET IN FLORIDA WITH MAY FESTIVAL SERVICE The biennial convention of the Fel· A festival service of thanksgi\,jng for Imvship of United Methodist Musicians the School of Sacred Music was held at will be held from Aug. 5 through Aug, Union Theological Seminary in New II at the Florida Southern College, York City on Sunday evening. May 6, Lakeland. Florida. The campus will pro· at 7:30 p.m. The school. which was \'ide a stimulating setting for thc con· founded in 1928 by Clarence Dickinson, l'emion. for it has become famous for concluded its distinguished forty-five its buildings designed by Frank Lloyd )'car history of training professional mu Wright. sicians for the church aher graduating Featured on this year's program will this year's class. be a con,"ocation 011 "Music and Archi· At the service, a choir of O\'er 250 tecture" under the dircction of architcct ,'Dices sang music by Parry, Brahms, Nils Schweizer, a studcnt of Frank Lloyd Haydn. Dickinson, Vaughan \\Tilliams, Wright. The com'ocation will divide in· Fc1ciano, Handel. and Bach. Since one to six groups following Mr, Schwe:zer's of the most important aspects of an ed talk. to tour six of the campus buildings. ucation at Union has been the respon· In cach building will be Ih'c music and sibility of each student to coordinate the interpreth'e slides. -

2017 Ago Mid-Atlantic Regional Convention

2017 AGO MID-ATLANTIC REGIONAL CONVENTION RICHMOND VIRGINIA June 25 – 28 WELCOME to Richmond and the Convention! We’re very glad you’ll be with us for what promises to be an invigorating and inspirational three-plus days. We hope the experiences you have will inform, challenge, delight, and refresh . and that you’ll leave with fantastic memories and a rejuvenated spirit. Please be sure to let us know how we can make your days here even more enjoyable. Don’t hesitate to ask questions. We love questions. We love trying to answer them. Relax, and let us guide you through a wonderful convention. Again, WELCOME ! 3 Bruce Stevens Recitals Masterclasses Organ Tours Christ the King Lutheran Church Richmond, Virginia AGO Chapter Workshops Casavant Frères, Opus 3108, 1971 The Organ Works of Josef Rheinberger Two Manuals Anton Heiller’s Perspectives on the Orgel-Büchlein Twenty-five Stops Twenty-nine Ranks Instructor of Organ, University of Richmond Historic Organ Study Tours (HOST) This instrument was moved from North [email protected] Carolina, Completely Rebuilt in our Baltimore workshop with All New Solid State Equipment, and Redesigned for a Dramatic Presence. Versatility was increased through Tonal Expansion and Revoicing. A Wonderful Organ, perfect for Christ The King Church. Another successful collaborative project with Casavant Frères. David M. Storey, Inc. Pipe Organ Building and Restoration Baltimore, Maryland Celebrating 35 Years of Professional Service Mid-Atlantic, Puerto Rico, Atlantic Canada 410-889-3800 [email protected] 4 Convention book designed, compiled, edited, and created by Bruce Stevens © 2017 All rights reserved Please report any mistakes in the printed infromation to the Convention Coordinator. -

The Westfield Center

The Westfield Center The Westfield Center was founded in 1979 by Lynn Edwards and Edward Pepe to fill a need for information about keyboard performance practice and instrument building in historical styles. In pursuing its mission to promote the study and appreciation of the organ and other keyboard instruments, the Westfield Center has become a vital public advocate for keyboard instruments and music. By bringing together professionals and an increasingly diverse music audience, the Center has inspired collaborations among organizations nationally and internationally. In 1999 Roger Sherman became Executive Director and developed several new projects for the Westfield Center, including a radio program, The Organ Loft, which is heard by 30,000 listeners in the Pacific Northwest; and a Westfield Concert Scholar program that promotes young keyboard artists with awareness of historical keyboard performance practice through mentorship and concert opportunities. In addition to these programs, the Westfield Center sponsors an annual conference about significant topics in keyboard performance. Since 2007 Annette Richards, Professor and University Organist at Cornell University, has been the Executive Director of Westfield, and has overseen a new initiative, the publication of Keyboard Perspectives, the Center’s Yearbook, which aims to become a leading journal in the field of keyboard studies. Since 2004, the Westfield Center has partnered with the Eastman School of Music as a cosponsor of the EROI Festival. 1 The Eastman Rochester Organ Initiative (EROI) When the Eastman School of Music opened its doors in 1921, it housed the largest and most lavish organ collection in the nation, befitting the interests of its founder, George Eastman. -

Anton Heiller Das Orgelwerkorgelwerk Vol

CYAN MAGENTA GELB SCHWARZ CYAN MAGENTA GELB SCHWARZ ANTON HEILLER DAS ORGELWERKORGELWERK VOL. 1 COMPLETECOMPLETE ORGAN WORKS c Martin Doerin ROMANROMAN SUMMEREDER » Bruckner-Orgel « g – www.die-orgelseite.de Stiftsbasilika St. Florian ACD-2027_Seite_28 ACD-2027_Seite_01 CYAN MAGENTA GELB SCHWARZ CYAN MAGENTA GELB SCHWARZ Anton Heiller (1923–1979) Anton Heiller – Phoenix aus der Asche auf alle Not und Bedrängnis der Zeit eingehende, Sämtliche Orgelwerke Vol. 1 / Complete Organ Works Vol. 1 aufrüttelnde Sprache, die vor allem kompromiss- Orgel und Orgelmusik waren und sind im öster- los wahr ist, aus der viel Liebe, Entsagung und (1.) Sonate (1944/45) 1 I Allegro non troppo 6:48 reichischen Musikleben nur marginal vertreten. Opferwillen redet und die dadurch befähigt ist, 2 II (manualiter) Lento – Più mosso – Tempo primo 7:53 Dennoch war es ein österreichischer Organist, wirklich zum Herzen der Menschen zu dringen. 3 III Con brio (Tempo di Toccata) 8:02 welcher der Orgelkultur im 20. Jh. entscheidende Dies ist es auch, was unsere neue Kirchenmusik Impulse verliehen hat: Anton Heiller. Von aussagen will. Zwei kleine Partiten (1947): romantischen Schlacken gereinigt war seine neu- Indessen war Heillers musikalische Ausbil- „Freu dich sehr, o meine Seele“ artige Bach-Interpretation geprägt von Anschlag dung gediegen bürgerlich, doch unspektakulär 4 I Sehr ruhig 1:21 und Tonbildung der wieder entdeckten mechani- verlaufen. In eine musikliebende Familie in 5 II Etwas fließender 0:53 schen Schleifladen-Orgel. Auf dieser Grundlage Wien-Dornbach hineingeboren, erhielt er Kla- 6 III Ein wenig lebhaft 1:19 hat Heiller Organisten weltweit und nachhaltig vierunterricht von seinem Vater, der dilettieren- 7 IV (Choral) Etwas breit, aber mit Schwung 1:17 geprägt. -

LRCD 1080 Booklet Final

MARK STEINBACH • ORGAN ORGAN WORKS OF ANTON HEILLER ORGAN WORKS OF ANTON PHOTO © rOger w. sHerman HEILLER MARK STEINBACH • ORGAN 1|Tanz-Toccata (1970) 5:55 2|Kleine Partita über das Dänische Lied 5:45 “Den klare sol går ned” (1977) 3|Passacaglia (ca. 1940/42) 8:20 4-6 | Kleine Partita “Es ist ein Ros’ entsprungen” (1944) 3:34 7|Verleih uns Frieden gnädiglich (1974) 1:29 8|Som lilliens hjerte kan holder I grøde (1977) 1:24 9-11 | Freu dich sehr, o meine Seele: 3:50 Vorspiel, Choral, Nachspiel y e l r e V 12-14 |Vorspiel, Zwischenspiel und Nachspiel aus der 13:52 e T c “Vesper” für Kantor, Chor und Orgel (1977) i d é n 15 | Jubilatio (1976) 5:03 é B . m © 16 | Orgelsatz: “Es ist ein Ros’ entsprungen” (1977) 1:36 O T O H TOTAL TIME: 50:48 P 2 THe cOmPOser lthough chiefly remembered today as an the human condition made more sense to me in the transform into quiet meditative solace. Above all, esteemed Bach interpreter and pedagogue, context of Vienna, the city of Freud, Mahler, Klimt, and Heiller’s music is highly visceral and demands an A Anton Heiller was also a virtuoso organist and Schoenberg. Both Vienna and Heiller’s music can elicit emotional response from the listener. prolific recording artist, as well as an accomplished feelings of existential angst and melancholy, but also of That Heiller’s compositions remain relatively improviser and conductor. With Heiller’s centenary ecstatic joy and humor. The m elancholy can also quickly unknown is at once strange and sad. -

• Forum 13 7.6.06 09.06.2006 10:47 Uhr Seite 1

• Forum 13_7.6.06 09.06.2006 10:47 Uhr Seite 1 13 2006 Die Orgelwerke The Organ Works · Les œuvres pour orgue • Forum 13_7.6.06 09.06.2006 10:47 Uhr Seite 2 INHALT · CONTENTS · SOMMAIRE EHRUNGEN 2006 3 ▼ HONOURS 2006 4 ▼ Impressum · Imprint · Impressum PRIX ET DISTINCTIONS 2006 4 Hindemith-Forum Mitteilungen der Hindemith-Stiftung/Bulletin of the Hindemith Foundation/Publication de DIE ORGELWERKE · THE ORGAN WORKS · la Fondation Hindemith Heft 13/Number 13/Cahier no 13 LES ŒUVRES POUR ORGUE © Hindemith-Institut, Frankfurt am Main 2006 Redaktion/Editor/Rédaction: Heinz-Jürgen Winkler TRUNKEN UND HEILIG-NÜCHTERN · Ein Beiträge/Contributors/Articles de: Bernhard Billeter (BB), Philosophische Gespräch mit dem Organisten Martin Lücker 7 ▼ Fakultät der Universität Zürich (PFUZ), Giselher Schubert (GS), Heinz-Jürgen DRUNKEN AND SAINTLY SOBER · A Conversa- Winkler (HJW) ▼ Redaktionsschluß/Copy deadline/ tion with the Organist Martin Lücker 9 Etat des informations: 15. Mai 2006 Hindemith-Institut NOYÉ, SAINT ET DÉPOUILLÉ · Un entretien avec Eschersheimer Landstr. 29-39 60322 Frankfurt am Main l’organiste Martin Lücker 11 Tel.: ++49-69-5 97 03 62 Fax: ++49-69-5 96 31 04 ▼ e-mail: [email protected] TRANSPARENZ UND MELANCHOLIE 13 internet: www.hindemith.org TRANSPARENCY AND MELANCHOLY 14 ▼ Gestaltung/Design/Graphisme: Stefan Weis, Mainz-Kastel TRANSPARENCE ET MÉLANCOLIE 16 Herstellung und Druck/Production and printing/Réalisation et impression: Schott Musik International, Mainz Forum 18 Übersetzung engl./English translation/ Traduction anglaise: -

Spread the Word. Promote the Show. Support Public Radio

A radio program for the king of instruments SPREAD THE WORD. PROMOTE THE SHOW. SUPPORT PUBLIC RADIO PROGRAM NO. 0901 1/5/2009 PROGRAM NO. 0902 1/12/2009 PROGRAM NO. 0903 1/19/2009 Going On Record…begin a New Year with a multi- At Large in Austria…a prelude to the upcoming Pipedreams Live! in Collegedale, Tennessee… national survey of sonically beguiling recent organ spring Pipedreams Organ Tour in the land of Mozart, instrument, artist, and audience participate in music recordings. Haydn, Beethoven, Brahms and Bruckner. improvised, played and sung. HERBERT SUMSION: Ceremonial March. GASTON GEORG MUFFAT: Toccata No. 1, from Apparatus Michael Barone was host for a special event featuring LITAIZE: Scherzo, from Douze Pieces –Herman musico-organisticus –Rupert Frieberger (1634 the Anton Heiller Memorial Organ at the Collegedale Jordaan (1962 Harrison & Harrison/St. Alban’s Putz+1708 Egedacher/Collegiate Church, Schlägl) Church of Southern Adventist University in Tennessee. Cathedral, England) Priory CD-863 Coronata CD-1216 With guest Dutch recitalist Sietze de Vries, he explored CHARLES STROUSE: Put on a Happy Face. J. S. BACH: Prelude & Fugue in e, S. 533 –Rupert and explained the varied sonic possibilities of John Bro- STEPHEN SONDHEIM: Send in the Clowns –Jelani Frieberger (1970 Hradetzky/Melk Abbey Church) mbaugh’s magnum opus tracker-action instrument from 1986 (with 70 stops, 108 ranks, and 4861 individual Eddington (1925 Midmer-Losch/Doubletree Canyon Stift Melk CD-1977 pipes). Gennevieve Brown-Kibble directed the campus Studio, Phoenix, AZ) RJE Productions CD-4920 W. A. MOZART: Gigue, K. 574 (1750 Mittenreiter/ Wallfahrtskirche, Arnsdorf). JAN BRANDTS choir and congregation in lusty song, to which Mr. -

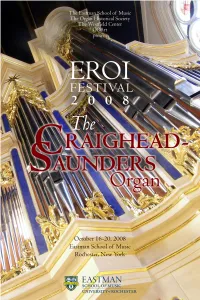

2008 EROI Program Book

2 EROI FESTIVAL 2008 SPONSORS: University of Rochester Press/Boydell & Brewer, Inc. Rochester Club Ballroom Constellation Center Westfield Center Howe & Rusling Investment Man- agement Organ Historical Society Rochester Chapter, American Guild of Organists Glenn E. Watkins Lecture Endowment at the Eastman School of Music Episcopal Diocese of Rochester Reformation Lutheran Church The Central New York Humanities Corridor, sponsored by the Andrew W. Mellon Foundation Sacred Heart Cathedral (RC) First Presbyterian Church, Pittsford Christ Church (Episcopal) Third Presbyterian Church Christ Church Schola Cantorum Boston Early Music Festival Parsons Pipe Organ Builders Pasi Organ Builders, Inc. Paul Fritts and Co. Organ Builders Richards Fowkes & Co. Pipe Organ Builders C. B. Fisk, Inc. Taylor and Boody Organ Builders Flentrop Organ Builders, The Netherlands Gerald Woehl Organ Builders, Ger- many GOArt, Göteborg University, Sweden Loft and Gothic Recordings Eastman School of Music EROI Working Committee Anonymous Anony- mous, in memory of James M. Winn, organist and pedagogue EROI WORKING COMMITTEE: Hans Davidsson, Professor of Organ and EROI Project Director Peter DuBois, Director of the Sacred Music Diploma Program David Higgs, Professor and Chair of the Organ Department Robert Kerner, Eastman Organ Technician Annie Laver, EROI Project Manager Patrick Macey, Professor and Chair of Musicology Elizabeth W. Marvin, Professor of Music Theory Jonathan Ortloff, Undergraduate EROI Assistant William Porter, Professor of Organ and Harpsichord Kerala J. Snyder, Professor of Musicology Emerita Daniel Zager, Associate Dean and Head Librarian of Sibley Music Library. EROI FESTIVAL 2009: October 29-November 1: Mendelssohn and the Contrapuntal Tradition 3 THE EASTMAN-ROCHESTER ORGAN INITIATIVE (EROI) When the Eastman School of Music opened its doors in 1921, it housed the largest and most lavish organ collection in the nation, befitting the interests of its founder, George Eastman. -

Omposers of Organ Music in the Romantic and Contemporary Periods {By Country)

• ~OMPOSERS OF ORGAN MUSIC IN THE ROMANTIC AND CONTEMPORARY PERIODS {BY COUNTRY) BOHEMIA AND PRESENT-DAY CZECHOSLOVAKIA *Petr Eben {1929 - ) *Leos Jan~cek {1854 - 1928) Karel Janecek (1903 - ) Miloslav Kabel~c {i908 - Kopelent Karel Luython Otmar Macha (1922 - ) Jiri Reinberger (1914 - ) Karel Reiner {1910 - ) Klement Slavicky (1910 - ) Milos Sokola (1913 - ) B.A. Wiedermann {1883 - 1951) CANADA *Gerald Bales (1919 - ) Keith Bissell (1912 - ) Maurice Boivin (1918 - ) Lynwood Farnam (1885 - 1930}· Frederick Karam (1926 - ) Fran~ois Morel (1926 - ) Vernon Murgatroyd {1918 - ) *Healy Willan (1880 - 1968) ENGLAND *Thomas Adams (1785 - 1858} *Sir Walter' Alcock (1861 - 1947) Thomas Atwood (1765 - 1838) William Thomas Best {1826 - 1897) Sir Edward Bairstow (1874 - 1946) *Frank Bridge (1879 - 1941) *Benjamin Britten (1913 - 1977) Brian BDJckless {1926 - } Sir Ernest Bullock Peter Dickinson (1934 - ) Harold Darke (1888 - 1977} *Ralph William Downes (1904 - ) *Sir Edward Elgar (1857 - 1934) *Percy Fletcher (1879 - 1932) Sebastian Forbes (1941 - } Peter Racine Fricker (1920 - ) *Iain Hamilton (1922 - ) Basil Harwood {1859 - 1949) -2- ENGLAND {cont'd) Alan Hoddinott (1939 - ) Alfred Hollins (1865 - 1942) *Herbert Howells (1892 - ) *Peter Hurford (1930 - ) John Ireland (1879 - 1962} Francis Jackson {1917 - ) *Craig Sellar Lang (1891 - 1971} *Kenneth Leighton (1929 - ) *William Matthias (1934 - ) Nicolas Maw (1935 - ) John McCabe (1939 - } George Oldroyd (1886 - 1951) *Sir c. Hubert H. Parry (1848 - 1918) *Simon Preston (1938 - } Alec Rowley {1902 - 1958) Francis Routh (1927 - } William Russell (1777 - 1813) Godfry Sceats *Sir Charles v. Stanford (1852 - 1924} *George Thalben-Ball (1896 - *Eric Thiman {1900 - 1959) *Michael Tippett (1905 - ) Thomas Atwood Walmesley (1765 - 1838) *Samuel Wesley {1766 - 1837) *Samuel Sebastian Wesley (1810 - 1876) *Percy Whitlock (1903 - 1946) *Ralph Vaughan Williams {1872 - 1958) *Malcolm Williamson (1931 - ) *Arthur Wills {1926 - ) Edward Wolstenholme *Charles Wood {1866 - 1926) FRANCE *Jehan Alain (1911 - 1940) . -

IMPROVISATION Musicological, Musical and Philosophical Aspects

3 ORGELPARK RESEARCH REPORTS VOLUME 3 VU UNIVERSITY PRESS VU UNIVERSITY IMPROVISATION Musicological, musical and philosophical aspects Orgelpark Research Report 3 THIRD EDITION (2020) EDITOR HANS FIDOM VU UNIVERSITY PRESS VU University Press De Boelelaan 1105 1081 HV Amsterdam The Netherlands www.vuuniversitypress.com [email protected] © 2013 (first edition), 2017 (second edition), 2020 (this edition) Orgelpark ISBN e-book/epub 978 94 91588 06 8 (available at www.orgelpark.nl) ISBN (this) paper edition 978 90 8659 718 5 (Report 3/1 and 3/2 combined) NUR 664 All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted, in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording, or otherwise, without the prior written consent of the publisher. Orgelpark Research Report 3 Contents [§1] Practical information 11 [§11] Introduction 13 Bruce Ellis Benson Béatrice Piertot [§23] In The Beginning, There Was Improvisation 17 [§326] Treatises about Improvisation on the Organ in Peter Planyavsky France from 1900 to 2009 167 [§57] Organ Improvisation in the Past Five Decades 37 Columba McCann [§84] European Improvisation History: Anton Heiller 51 [§396] Marcel Dupré 193 Pamela Ruiter-Feenstra Gary Verkade [§110] Bach and the Art of Improvisation 63 [§550] Teaching Free Improvisation 265 Sietze de Vries Vincent Thévenaz [§140] The Craft of Organ Improvisation 83 [§566] A Contemporary Improvisation on a Baroque Theme Bernhard Haas and a Romantic Organ 273 [§167] Improvisation, C.Ph.E.