The Monstrous and the Horrible in Alien Resurrection1

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Retriever, Issue 1, Volume 39

18 Features August 31, 2004 THE RETRIEVER Alien vs. Predator: as usual, humans screwed it up Courtesy of 20th Century Fox DOUGLAS MILLER After some groundbreaking discoveries on Retriever Weekly Editorial Staff the part of the humans, three Predators show up and it is revealed that the temple functions as prov- Many of the staple genre franchises that chil- ing ground for young Predator warriors. As the dren of the 1980’s grew up with like Nightmare on first alien warriors are born, chaos ensues – with Elm street or Halloween are now over twenty years Weyland’s team stuck right in the middle. Of old and are beginning to loose appeal, both with course, lots of people and monsters die. their original audience and the next generation of Observant fans will notice that Anderson’s filmgoers. One technique Hollywood has been story is very similar his own Resident Evil, but it exploiting recently to breath life into dying fran- works much better here. His premise is actually chises is to combine the keystone character from sort of interesting – especially ideas like Predator one’s with another’s – usually ending up with a involvement in our own development. Anderson “versus” film. Freddy vs. Jason was the first, and tries to allow his story to unfold and build in the now we have Alien vs. Predator, which certainly style of Alien, withholding the monsters almost will not be the last. Already, the studios have toyed altogether until the second half of the film. This around with making Superman vs. Batman, does not exactly work. -

Jun 18 Customer Order Form

#369 | JUN19 PREVIEWS world.com Name: ORDERS DUE JUN 18 THE COMIC SHOP’S CATALOG PREVIEWSPREVIEWS CUSTOMER ORDER FORM Jun19 Cover ROF and COF.indd 1 5/9/2019 3:08:57 PM June19 Humanoids Ad.indd 1 5/9/2019 3:15:02 PM SPAWN #300 MARVEL ACTION: IMAGE COMICS CAPTAIN MARVEL #1 IDW PUBLISHING BATMAN/SUPERMAN #1 DC COMICS COFFIN BOUND #1 GLOW VERSUS IMAGE COMICS THE STAR PRIMAS TP IDW PUBLISHING BATMAN VS. RA’S AL GHUL #1 DC COMICS BERSERKER UNBOUND #1 DARK HORSE COMICS THE DEATH-DEFYING DEVIL #1 DYNAMITE ENTERTAINMENT MARVEL COMICS #1000 MARVEL COMICS HELLBOY AND THE B.P.R.D.: SATURN RETURNS #1 ONCE & FUTURE #1 DARK HORSE COMICS BOOM! STUDIOS Jun19 Gem Page.indd 1 5/9/2019 3:24:56 PM FEATURED ITEMS COMIC BOOKS & GRAPHIC NOVELS Bad Reception #1 l AFTERSHOCK COMICS The Flash: Crossover Crisis Book 1: Green Arrow’s Perfect Shot HC l AMULET BOOKS Archie: The Married Life 10 Years Later #1 l ARCHIE COMICS Warrior Nun: Dora #1 l AVATAR PRESS INC Star Wars: Rey and Pals HC l CHRONICLE BOOKS 1 Lady Death Masterpieces: The Art of Lady Death HC l COFFIN COMICS 1 Oswald the Lucky Rabbit: The Search for the Lost Disney Cartoons l DISNEY EDITIONS Moomin: The Lars Jansson Edition Deluxe Slipcase l DRAWN & QUARTERLY The Poe Clan Volume 1 HC l FANTAGRAPHICS BOOKS Cycle of the Werewolf SC l GALLERY 13 Ranx HC l HEAVY METAL MAGAZINE Superman and Wonder Woman With Collectibles HC l HERO COLLECTOR Omni #1 l HUMANOIDS The Black Mage GN l ONI PRESS The Rot Volume 1 TP l SOURCE POINT PRESS Snowpiercer Hc Vol 04 Extinction l TITAN COMICS Lenore #1 l TITAN COMICS Disney’s The Lion King: The Official Movie Special l TITAN COMICS The Art and Making of The Expance HC l TITAN BOOKS Doctor Mirage #1 l VALIANT ENTERTAINMENT The Mall #1 l VAULT COMICS MANGA 2 2 World’s End Harem: Fantasia Volume 1 GN l GHOST SHIP My Hero Academia Smash! Volume 1 GN l VIZ MEDIA Kingdom Hearts: Re:Coded SC l YEN ON Overlord a la Carte Volume 1 GN l YEN PRESS Arifureta: Commonplace to the World’s Strongest Zero Vol. -

From Jeunet's Alien: Resurrection

ACTA UNIV. SAPIENTIAE, FILM AND MEDIA STUDIES, 8 (2014) 149–166 DOI: 10.2478/ausfm-2014-0031 Embodied Genetics in Science-Fiction, Big-Budget to Low-Budget: from Jeunet’s Alien: Resurrection (1997) to Piccinini’s Workshop (2011) Andrea Virginás Sapientia Hungarian University of Transylvania (Cluj-Napoca, Romania) E-mail: [email protected] Abstract. The article uses and revises to some extent Vivian Sobchack’s categorization of (basically) American science-l ction output as “optimistic big-budget,” “wondrous middle-ground” and “pessimistic low-budget” seen as such in relation to what Sobchack calls the “double view” of alien beings in l lmic diegesis (Screening Space, 2001). The argument is advanced that based on how diegetic encounters are constructed between “genetically classical” human agents and beings only partially “genetically classical” and/or human (due to genetic diseases, mutations, splicing, and cloning), we may differentiate between various methods of visualization (nicknamed “the museum,” “the lookalike,” and “incest”) that are correlated to Sobchack’s mentioned categories, while also displaying changes in tone. Possibilities of revision appear thanks to the later timeframe (the late 1990s/2000s) and the different national-canonical belongings (American, Icelandic-German- Danish, Hungarian-German, Canadian-French-American, and Australian) that characterize l lmic and artistic examples chosen for analysis as compared to Sobchack’s work in Screening Space.1 Keywords: science-l ction, genetic mutations, aliens, Vivian Sobchack. Hero(ines) Facing Genetic Aliens In her exceptional monograph about modern American science-l ction cinema, Screening Space (2001), Vivian Sobchack writes in detail about “the alien’s perspective,” the creature that not only is different from us, but, as a matter of fact, cannot be conceived of from the standpoint we, humans, occupy, neither 1 This work was supported by a grant of the Romanian Ministry of Education, CNCS – UEFISCDI, project number PN-II-RU-PD-2012-3 – 0199. -

Women in Film Time: Forty Years of the Alien Series (1979–2019)

IAFOR Journal of Arts & Humanities Volume 6 – Issue 2 – Autumn 2019 Women in Film Time: Forty Years of the Alien Series (1979–2019) Susan George, University of Delhi, India. Abstract Cultural theorists have had much to read into the Alien science fiction film series, with assessments that commonly focus on a central female ‘heroine,’ cast in narratives that hinge on themes of motherhood, female monstrosity, birth/death metaphors, empire, colony, capitalism, and so on. The films’ overarching concerns with the paradoxes of nature, culture, body and external materiality, lead us to concur with Stephen Mulhall’s conclusion that these concerns revolve around the issue of “the relation of human identity to embodiment”. This paper uses these cultural readings as an entry point for a tangential study of the Alien films centring on the subject of time. Spanning the entire series of four original films and two recent prequels, this essay questions whether the Alien series makes that cerebral effort to investigate the operations of “the feminine” through the space of horror/adventure/science fiction, and whether the films also produce any deliberate comment on either the lived experience of women’s time in these genres, or of film time in these genres as perceived by the female viewer. Keywords: Alien, SF, time, feminine, film 59 IAFOR Journal of Arts & Humanities Volume 6 – Issue 2 – Autumn 2019 Alien Films that Philosophise Ridley Scott’s 1979 S/F-horror film Alien spawned not only a remarkable forty-year cinema obsession that has resulted in six specific franchise sequels and prequels till date, but also a considerable amount of scholarly interest around the series. -

Aliens, Predators and Global Issues: the Evolution of a Narrative Formula

CULTURA , LENGUAJE Y REPRESENTACIÓN / CULTURE , LANGUAGE AND REPRESENTATION ˙ ISSN 1697-7750 · VOL . VIII \ 2010, pp. 43-55 REVISTA DE ESTUDIOS CULTURALES DE LA UNIVERSITAT JAUME I / CULTURAL STUDIES JOURNAL OF UNIVERSITAT JAUME I Aliens, Predators and Global Issues: The Evolution of a Narrative Formula ZELMA CATALAN SOFIA UNIVERSITY ABSTRACT : The article tackles the genre of science fiction in film by focusing on the Alien and Predator series and their crossover. By resorting to “the fictional worlds” theory (Dolezel, 1998), the relationship between the fictional and the real is examined so as to show how these films refract political issues in various symbolic ways, with special reference to the ideological construct of “global threat”. Keywords: film, science fiction, narrative, allegory, otherness, fictional worlds. RESUMEN : en este artículo se aborda el género de la ciencia ficción en el cine mediante el análisis de las películas de la serie Alien y Predator y su combinación. Utilizando la teoría de “los mundos ficcionales” (Dolezel, 1999), se examina la relación entre los planos ficcional y real para mostrar cómo estas películas reflejan cuestiones políticas de diversas formas simbólicas, con especial referencia a la construccción ideológica de la “amenaza global”. Palabras clave: film, ciencia ficción, narrativa, alegoría, alteridad, mundos fic- cionales In 2004 20th Century Fox released Alien vs. Predator, directed by Paul Anderson and starring Sanaa Latham, Lance Henriksen, Raoul Bova and Ewen Bremmer. The film combined and continued two highly successful film series: those of the 1979 Alien and its three successors Aliens (1986), Alien 3 (1992) and Alien Resurrection (1997), and of the two Predator movies, from 1987 and 1990 respectively. -

Build a Be4er Neplix, Win a Million Dollars?

Build a Be)er Ne,lix, Win a Million Dollars? Lester Mackey 2012 USA Science and Engineering FesDval Nelix • Rents & streams movies and TV shows • 100,000 movie Dtles • 26 million customers Recommends “Movies You’ll ♥” Recommending Movies You’ll ♥ Hated it! Loved it! Recommending Movies You’ll ♥ Recommending Movies You’ll ♥ How This Works Top Secret Now I’m Cinematch Computer Program I don’t unhappy! like this movie. Your Predicted Rang: Back at Ne,lix How can we Let’s have a improve contest! Cinematch? What should the prize be? How about $1 million? The Ne,lix Prize October 2, 2006 • Contest open to the world • 100 million movie rangs released to public • Goal: Create computer program to predict rangs • $1 Million Grand Prize for beang Cinematch accuracy by 10% • $50,000 Progress Prize for the team with the best predicDons each year 5,100 teams from 186 countries entered Dinosaur Planet David Weiss David Lin Lester Mackey Team Dinosaur Planet The Rangs • Training Set – What computer programs use to learn customer preferences – Each entry: July 5, 1999 – 100,500,000 rangs in total – 480,000 customers and 18,000 movies The Rangs: A Closer Look Highest Rated Movies The Shawshank RedempDon Lord of the Rings: The Return of the King Raiders of the Lost Ark Lord of the Rings: The Two Towers Finding Nemo The Green Mile Most Divisive Movies Fahrenheit 9/11 Napoleon Dynamite Pearl Harbor Miss Congeniality Lost in Translaon The Royal Tenenbaums How the Contest Worked • Quiz Set & Test Set – Used to evaluate accuracy of computer programs – Each entry: Rang Sept. -

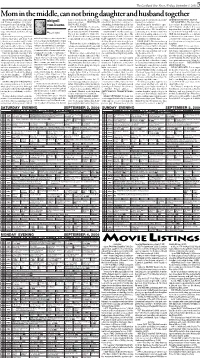

Mom in the Middle, Can Not Bring Daughter and Husband Together DEAR ABBY: I Was Recently Mar- Want to Tell Them Who Did It

The Goodland Star-News / Friday, September 1, 2006 5 Mom in the middle, can not bring daughter and husband together DEAR ABBY: I was recently mar- want to tell them who did it. I really coming a young woman, and sharing transsexual. Your friend needs under- BRENDA IN AUSTIN, TEXAS ried. I have a daughter, “Courtney,” abigail need some advice. — HURTING IN a bed with her father could be too standing, not isolation. DEAR BRENDA: The type of par- from a previous relationship. Things van buren HAYWARD, CALIF. stimulating, for both of them. If he has By all means he should see a psy- ties you have described are more for were great before the wedding. We DEAR HURTING: Pick up the further doubts about this, he should chiatrist — one who specializes in adults than for children. It is more even included Courtney in the plan- phone and call the Rape, Abuse and consult his daughter’s pediatrician. gender disorders. He should have important that your little girl be able ning. Afterward, however, things Incest National Network (RAINN). DEAR ABBY: About a month ago, counseling if he wants to take this to enjoy her birthday with some of dear abby turned sour. • The toll-free number is (800) 656- I was shocked out of my shoes. My where it is heading, and also to cope HER friends than it be a command Courtney kept causing problems 4673. Counselors there will guide you longtime friend, “Orville,” told me he with the loss of his friends. It would performance for your sisters. -

Alien Movie Franchise

Bellies that Go Bump in the Night The Gothic Curriculum of Essential Motherhood in the Alien Movie Franchise KELLY WALDROP The Publish House OR CENTURIES, authors and storytellers have used Gothic tales to educate readers about F all manner of subjects, but one of the most common of those subjects is the question of what it means to be human (Bronfen, 2014). The Gothic genre was born amidst the transition from the Victorian era to the Modern era with all of the attendant social and cultural changes, as well as the anxieties, that came along with those changes (Riquelme, 2014). It is a genre rooted in the exploration of anxieties regarding social and cultural change. Taking two of the earliest examples from the European Gothic tradition, Dracula (Stoker, 1897) teaches readers about the dangers of a rampant and virulent sexuality (Riquelme, 2000), while Frankenstein (Shelley, 1818) warns of both obsessiveness and pride, among many other readings of the various cultural anxieties that may be seen to be aired in these works. In these classic Gothic tales, a key focus is also the horrific results of an out-of-control and “unnatural” form of reproduction. In Dracula, part of the horror is rooted in a generative process that is outside of that of the male/female sex act that produces a child. The women in the story are either victims of the tale (Jonathan Harker’s fiancé) or are depicted as frighteningly sexual while incapable of producing what would be considered normal offspring (Dracula’s brides). In Frankenstein, likewise, the central source of horror is the product of a man usurping the “natural” order of creation. -

Approved Movie List 10-9-12

APPROVED NSH MOVIE SCREENING COMMITTEE R-RATED and NON-RATED MOVIE LIST Updated October 9, 2012 (Newly added films are in the shaded rows at the top of the list beginning on page 1.) Film Title ALEXANDER THE GREAT (1968) ANCHORMAN (2004) APACHES (also named APACHEN)(1973) BULLITT (1968) CABARET (1972) CARNAGE (2011) CINCINNATI KID, THE (1965) COPS CRUDE IMPACT (2006) DAVE CHAPPEL SHOW (2003–2006) DICK CAVETT SHOW (1968–1972) DUMB AND DUMBER (1994) EAST OF EDEN (1965) ELIZABETH (1998) ERIN BROCOVICH (2000) FISH CALLED WANDA (1988) GALACTICA 1980 GYPSY (1962) HIGH SCHOOL SPORTS FOCUS (1999-2007) HIP HOP AWARDS 2007 IN THE LOOP (2009) INSIDE DAISY CLOVER (1965) IRAQ FOR SALE: THE WAR PROFITEERS (2006) JEEVES & WOOSTER (British TV Series) JERRY SPRINGER SHOW (not Too Hot for TV) MAN WHO SHOT LIBERTY VALANCE, THE (1962) MATA HARI (1931) MILK (2008) NBA PLAYOFFS (ESPN)(2009) NIAGARA MOTEL (2006) ON THE ROAD WITH CHARLES KURALT PECKER (1998) PRODUCERS, THE (1968) QUIET MAN, THE (1952) REAL GHOST STORIES (Documentary) RICK STEVES TRAVEL SHOW (PBS) SEX AND THE SINGLE GIRL (1964) SITTING BULL (1954) SMALLEST SHOW ON EARTH, THE (1957) SPLENDER IN THE GRASS APPROVED NSH MOVIE SCREENING COMMITTEE R-RATED and NON-RATED MOVIE LIST Updated October 9, 2012 (Newly added films are in the shaded rows at the top of the list beginning on page 1.) Film Title TAMING OF THE SHREW (1967) TIME OF FAVOR (2000) TOLL BOOTH, THE (2004) TOMORROW SHOW w/ Tom Snyder TOP GEAR (BBC TV show) TOP GEAR (TV Series) UNCOVERED: THE WAR ON IRAQ (2004) VAMPIRE SECRETS (History -

Prometheus ©Twentieth Century Fox ©Twentieth Directed By: Ridley Scott

Prometheus ©Twentieth Century Fox ©Twentieth DirecteD by: Ridley Scott certificate: 15 running time: 123 mins country: UK/USA year: 2012 KeyworDs: science fiction, film franchise, action heroine, faith suitable for: 14–19 media/film studies, religious education www.filmeducation.org 1 ©Film Education 2012. Film Education is not responsible for the content of external sites synoPsis Ridley Scott, director of ‘Alien’ and ‘Blade Runner,’ returns to the genre he helped define. With Prometheus, he creates a groundbreaking mythology, in which a team of explorers discover a clue to the origins of mankind on Earth, leading them on a thrilling journey to the darkest corners of the universe. There, they must fight a terrifying battle to save the future of the human race. before Viewing the original ‘alien’ series Alien (Ridley Scott, 1979) – Aliens (James Cameron, 1986) – Alien 3 (David Fincher, 1992) – Alien Resurrection (Jean-Pierre Jeunet, 1997) Prometheus is an eagerly awaited science fiction adventure from Alien director Ridley Scott. In the run-up to its release, anticipation for this film was at fever pitch because it returns to a world created by Scott in the sci-fi horror classic Alien. The four original Alien films share certain things in common: ■ All were directed by visionary filmmakers at the very beginning of their career (Alien 3 was David Fincher’s first film and Alien Resurrection was the Hollywood debut of Amélie director Jean-Pierre Jeunet). ■ Each film features the same female protagonist - Ripley (Sigourney eaver).W ■ Whilst all four are science fiction films, each has the framework of other genres. -

WEB BEN 4.Pdf

IL TM Il mensile gratuito sullo star bene aprile N. 4 2012 Campione di Benessere Max Biaggi Make up Novità di primavera Alimentazione Sorprendente frutta secca find us on: SOMMARIO EDITORIALE 10 32 Care Lettrici e cari Lettori, ritroviamo il nostro ritmo Nel Terzo Millennio, da quando ci si alza al mattino fino a quando ci si corica la sera, si va sempre di corsa. Tempi stretti, mille impe- 20 36 gni, difficoltà negli spostamenti ci inducono a ritmi sempre più frenetici, per nulla amici del benessere. Impariamo, perciò, a dare un nuovo significato alla parola “velocità”. Gra- zie al campione delle due ruote Max Biaggi scopriamo come l’andatura sostenuta pos- sa essere un’inestimabile fonte di energia e di soddisfazioni. Invece, il pilota spoletino Mauro Cesari, sempre pronto a nuove av- venture, evidenzia come vivere a tutto gas sia sinonimo di solerzia, alacrità, dinamismo. 40 E la giovanissima Vittoria “Vicky” Piria, peru- gina acquisita al debutto nel mondo delle corse, ci racconta di come, per inseguire un sogno, basti premere il piede sull’accelera- tore. Così, una volta che ci si è riappropriati dei propri tempi, si può tornare a godere dei piccoli piaceri quotidiani. Come una benefi- ca pedalata nel verde che, pur svolgendosi su due ruote spesso dotate di marce, non ri- chiede necessariamente di correre. O come la cura di noi stessi, che passa anche per l’ultimo make up alla moda. 46 58 66 FITNESS Una pedalata di salute 10 IL PERSONAGGIO Max Biaggi Campione 52 di BENessere 20 LENTE D’INGRANDIMENTO Mauro Cesari Spoleto scende 70 in pista 32 STILI DI VITA Sport ed ecologia 36 IL PERSONAGGIO Vicky Piria Quella marcia in più 40 E ANCORA.. -

Love, Sex and Salvation in the Whedonverse

Queering Messiahs 177 Queering Messiahs: Love, Sex and Salvation in the Whedonverse by Sofia Sjö The article explores the question of religion and sexuality using popular cultural representations as a discussion partner. The focus is on the sexuality of savior characters in the imaginary worlds of the American film and Tv-series maker Joss Whedon. The analysis shows that several references to Christianity and obvious Christ characters can be identified in the material, nut also clear challenges of Christian ideals. The complex portrayals of both saviors and sexuality in the Whedonverse are argued to point to some ineresting and noteworthy aspects of sex and Christianity in a contemporary context. issues that are brought to the surface refer to the importance of sex and love and problems with seeing sex ad inherently good or bad. In the article, the essentialness of a space where the issue of religion and sex can be explored is stressed and the need for the discussion to continue is underlined. 1. Introduction To understand the world of today one cannot ignore the worlds of popular culture. These imaginary worlds both influence and reflect us. In them we can find traditional thoughts and ideas, but also fascinating challenges of our ideals and practices. Therefore, it is not that surpris- ing that many scholars nowadays turn to popular culture when they want to understand perspectives of our contemporary world. This is true for scholars of religion and theology as well. As many studies have shown, popular culture is rich with religious possibilities. In them we can find mythic motives,1 reflections of a modern spirituality2 and themes that inspire theological thought.3 The purpose of this article is to build on an area of research in the field of religion and film that has already produced some interesting studies.