Provides Resources to Support All of These

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Bishop's Synod Charge 2009 the Rt Rev'd Gregory E Thompson

The Bishop’s Synod Charge 2009 The Rt Rev’d Gregory E Thompson Welcome to the thirtieth synod of the Diocese of the Northern Territory. I acknowledge the traditional custodians, the Larrakia people on whose land we meet in order to give thanks for God’s faithfulness to us, to hear the stories and concerns on our hearts and minds and to seek to serve Christ with our best energies and insight for our Diocese and for the people of the Northern Territory. A Cord of Grace, Goodwill and Common Purpose When I travel this Diocese of over 1.3 million square kilometres, featuring desert, coastal, billabong, urban, outstation and agency communities, I wonder at the unique gifting of the landscape, cultures and the people that are within our Diocesan community. With such breadth and beauty comes extraordinary opportunity in our mission as Christ’s people but also these qualities bring significant tensions of holding our life together in its diversity and distance. I imagine often our church and community life like a string of pearls or precious gems from the Arafura Sea to the Simpson Desert – each pearl or gem unique but each one reliant on a cord of grace, goodwill and common purpose. Without the cord running through our different communities we are isolated and vulnerable before the social and spiritual challenges before us. Without a shared sense of direction under the good purposes of God, our contribution to God’s mission is unsustainable, for the weak give up without help and the strong in their own independence are not able to receive the necessary gifts from others. -

Kormildanews Kormilda College Darwin NT | Term 3 Edition 12 | 25 August 2011

KormildaNEWS Kormilda College Darwin NT | Term 3 Edition 12 | 25 August 2011 Principal’s Perspective AUGUST Many thanks to all parents, students and sta who took the time to complete the re- Thur 25 to Mon 29 cent on-line surveys. Summary reports of the results are available on our website un- Year 11 Outdoor Education Camp der Information For/Current Parents. As mentioned previously, the Board and senior Group 3 – Gunlom Region, Kakadu sta will be using the results to set priorities and directions for the next Strategic Plan. Fri 26 Year 7 students will shortly be using an iPad for their studies. The College Learning Flinders University Presentation Technologies team and a number of sta have been planning how best to use these 12.30pm in the Careers Centre. For new technologies in class contexts and the Year 7 students will take part in a trial Year 12s, but all students welcome. that will involve using the iPads in all their lessons. It is important to note that just Tue 30 because a particular technology exists, does not necessarily mean it can be used Languages Evening 5.00 - 6.30pm to enhance learning. Our Year 7s will help the College plan for the e ective use of in the Auditorium. For Languages these devices in the classroom. Needless to say, sta involved in the trial are very students, special guests, parents & excited to be using the new devices and have spent a considerable amount of time friends. Join us! in preparation and in professional development. Special thanks to those students Wed 31 who have volunteered as ‘iAssist’s’ to help with the implementation of the iPads. -

2014 International Conference Awards Feature Certified Advancement Practitioner Training Our First Ambassador

November 2014 2014 International Conference Awards Feature Certified Advancement Practitioner Training Our First Ambassador FEATURED ARTICLES The Changed Face of Crisis Communications Sam Elam The Science of Viral Content Strategy Cameron Pegg Creating a High Performance Leadership Culture Jeremy Carter How do we Solve a Problem like Generation Y? Harmonie Farrow Five Lessons in Campaign Management Brian Bowamn WE CONSULT, CREATE & PRODUCE VIDEOS FOR EDUCATION Producing compelling, fast-paced content through the eyes of entertainment with our primary focus on the youth market. (Education Packages start from $5,000) WWW.DEPARTMENTOFTHEFUTURE.COM.AU [email protected] CONTACT US: +613 9822 6451 2 EDUCATE PLUS Contents 03 The Board 2014 04 From the Chair 06-7 From the CEO 08-12 Conference 2014 14-15 Gala Event 16-17 Educate Plus Ambassador Program 18-19 Creating Leadership Culture 20-21 How do we solve the problem of Gen Y 23 Breakfast Blitz 24-29 Awards for Excellence 2014 30-33 Feature Awards 34-35 The Science of Viral Content Strategy 37-38 Five Lessons in Campaign 40-41 The Changed Face Of Crisis Communications 43 Certified Advancement Practitioner Training 45 Honouring our Fellows 46 Upcoming Chapter Conferences 47-48 Our Members Publication of Educate Plus ABN 48294772460 Enquiries: Georgina Gain, Marketing & Communications Manager, Educate Plus T +61 2 9489 0085 [email protected] www.educateplus.edu.au Cover Photo: International Conference Committee at the Conference Gala Dinner All Conference Photos by Photo Hendriks www.photohendriks.com.au Layout by Relax Design www.relaxdesign.com.au Printed by Lindsay Yates Group www.lyg.net.au All conference photos credited to Photo Hendriks FACE2FACE Nov 2014 1 Experience c unts. -

3. Minutes of 2017

IB Schools Australasia Annual General Meeting Minutes Friday 1 September, 2017 Flockart Hall METHODIST LADIES COLLEGE 207 Barkers Road Kew VIC 3101 9:30am – 11.00am INTRODUCTION Ashley Coats, Chair, IB Schools Australasia opened the 2017 AGM with a welcome to all those present and a thank you for all those who have attended in person this year. APOLOGIES The following list of attendees and apologies was accepted by the Chair: Postal vote Name of Member Acceptance Apology form School received ACG Senior College Tracy Dykstra Yes Al Zahra College Wissam Mustapha, Principal Yes Albert Park College Annesley College Aspendale Gardens Dr Cheryle Primary School Osborne Australian International Ms Irene Kakoulis Academy of and Mr Kumaravell Education, Victoria Sepulohniam Australian International Academy, Kellyville Campus Australian International Academy, Strathfield Campus Ballarat Grammar Benowa State High School Blackwood High School Kate Young Yes Canberra Girls Grammar School Anne Coutts, Principal Yes Canberra Grammar School Justin Garrick Tracy Maynard Yes THE ASSOCIATION OF AUSTRALASIAN IB SCHOOLS INC. TRADING PO Box 823 [email protected] AS IB SCHOOLS AUSTRALASIA ABN 38 129 667 431 / A22426 Heathmont VIC 3135 www.ibaustralasia.org Carey Baptist Grammar School Philip Grutzner, Principal Yes Chilton Saint James School Cleveland District Karen Abraham State High School Robyn Przewloka Concordia College - Aliki Papapetros Coromandel Valley Primary School Cranbrook School Genet Erickson- Adam Yes Diocesan School for Girls Susan Marriott -

School Fees Report 2019 Introduction

School Fees Report 2019 Introduction With one in three Australian families sending their child to a non- Government school, private school fees are a huge investment for parents. Edstart’s School Fees Report helps you understand the trends in private school fees across the country. This year’s report analysed fees from over 300 schools, covering tuition, compulsory additional fees and boarding fees. Overall Trends Private school fees across Australia have risen by an average of 3.1% in 2019, which is slightly down from 3.2% last year. While almost 9% of schools reduced their fees or had no fee change, we found that over 84% of schools increased their fees by more than the current inflation rate of 1.8%*. Fee inflation also continued to outpace the average wage growth rate of 2.2%. While there was a small drop in school fee inflation this year, state-based fee analysis showed significant geographic variances. NSW and Victoria continued to lead the way with the highest average school fees and smallest percentage of schools where fees remained the same or were reduced. Western Australia saw the highest percentage of schools that did not raise their fees in 2019 and the lowest average increase in fees at merely 1.58%. On the other hand, ACT showed the highest fee increase of 5.07%. These statewide trends are caused by some of the key themes that are explained further below. A Tale of Three Parts While overall school fee trends were consistent with prior years, 2019 has generated the largest variety of school fee changes in many years. -

Education for All. South East Asia and South Pacific Sub-Regional

DOCUMENT RESUME ED 332 852 RC 018 161 AUTHOR Devlin, Brian C., Ed. TITLE Education for All. South East Asia andSouth Pacific Si:lip-Regional Conference Report (Darwin,Northern Territory, Australia, October 14-19, 1990). INSTITUTION Northern Territory Dept. of Education,Darwin (Australia). SPONS AGENCY Australian Dept. of Employment, Educationand Training, Canberra.; Australian International Development Assistance Bureau.; International Literacy Year Secretariat, Canberra (Australia).; United Nations Educational, Scientificand Cultural Organization, Bangkok (Thailand). PrincipalRegional Office for Asia and the Pacific. REPORT NO ISBN-0-7245-2500-9 PUB DATE 91 NOTE 232p. PUB TYPE Collected Works - Conference Proceedings(021) EDRS PRICE MF01/PC10 Plus Postage. DESCRIPTORS Access to Education; Adult Education;Bilingual Education; *Disabilities; Education Work Relationship; Elementary SecondaryEducation; Equal Education; Foreign Countries; *Indigenous Populations; *Literacy Education; Multicultural Education; Poverty; *Rural Education;Teacher Education; *Womens Education IDENTIFIERS *Asia (Southeast); Australia; PacificIslands; *South Pacific ABSTRACT In October 1990, 223 delegates from 22nations of Southeast Asia and the South Pacific metin Australia to discuss plans and strategies for achieving universaleducation in the region. To inform planning and action, theconference defined fivegroups of people for whom universal education isa priority: indigenous people and minorities, people in poverty,people in remote areas,people with disabilities, -

Submission to Joint Select Committee on Northern Australia

Submission Number: 174 Date received: 14/03/14 Submission to Joint Select Committee on Northern Australia Terms of Reference: Identify the critical economic and social infrastructure needed to support the long term growth of the region, and ways to support planning and investment in that infrastructure. www.kormilda.nt.edu.au Kormilda College Towards tomorrow An Anglican and Uniting Church College Submission: Joint Select Committee on Northern Australia Terms of Reference addressed: Identify the critical economic and social infrastructure needed to support the long term growth of the region, and ways to support planning and investment in that infrastructure. March 2014 Kormilda College Mission Statement Kormilda College, from its Christian foundation and commitment to excellence, seeks to inspire its students to be life-long learners who act with compassion and justice through their understanding of others, and who develop the wisdom and courage to shape the future. Table of Contents 1. Introduction 4 2. Background 6 3. Considerations 8 4. Way Forward 9 5. Advantages 10 6. Appendice 11 Submission to Joint Select Committee on Northern Australia 3 1. Introduction Darwin has long held the desire to have its own prestigious, top of the market education facility, attractive not only to Territory students, but also the Northern Australian region and its nearby international neighbours, some as close as less than one hour flying time to Darwin. The Darwin International Grammar School concept was first raised in the early 1980’s when a group of leading local businessmen pursued the dream of a premium, private school that they saw was an important foundation not only for their own children, but as a lasting legacy for future generations. -

Advertising Tasmania's Boarding Schools

Vol 07 | Quarterly Magazine Issue 02 | June 2014 Agfest 2014 - Advertising Tasmania’s Boarding Schools CONTENTS Beducation - 02 Beducation 04 Investment in Boarding Courtesy of Technology 06 The Line Between Boarding and Living on a Farm 08 Komilda Food Forum 09 Indigenous Dancers Perform 10 Introverts AUTHOR Imagine you are a student at any one of the 12 The Subscription Economy Dr Michael Carr-Gregg great Boarding schools that come under the 13 Boarder Captains Come Together Director umbrella of the Australian Boarding Schools 14 New Principals & Heads of Young and Well Cooperative Research Centre Association. It is about 6.30 am and the stu- Boarding dents are still fast asleep. 15 Attributes of a Good Bloke 16 Productivity, Creativity and Noise But one by one, they stir, woken by a soft vi- bration on their wrist, timed to start buzzing 18 You will be Known for your at the lightest point in their sleep cycle. They Footprints press a button on their hi-tech bracelet to tell 20 Top 5 Tips for Dealing with it they’re awake, and immediately plug it into Challenging Students their iPod, iPhone, or iPad to find out how well 22 How to Recover When you Feel they’ve slept. After a few seconds, a graph pops up to tell them how much deep sleep you’ve been Wronged they have had. They log how they feel by 24 Home Away From Home? touching a happy or sad face on their screen. 26 Singapore Boarding Schools They note that many of their fellow students 28 Positive Education on a Shoestring! are doing the same as their sleep charts pop 30 Exchange Program Expands up on their news feed. -

Religious Education in Uniting Church Schools A

Religious Education in Uniting Church schools A framework 3 Contents Foreword 5 Introduction 7 Background and rationale 7 Source materials 7 Introduction 7 Purpose 8 Part A: Religious Education framework 9 RE in a Uniting Church context 11 A Uniting Church theology of education 11 Faith formation or academic subject? 11 Aims and outcomes 12 Assessment 13 Modelling learning 13 Key learning domains and guiding principles 14 Four learning verbs 17 Principles of curriculum design 21 RE in the timetable 21 Inquiry based learning 21 Collaborative and co-curricular projects 22 The Uniting Church in Australia Forms of assessment 23 Schools and Residential Colleges Commission Part B: Scope and sequence 25 Whole school planning 26 Copyright Guiding principles in the curriculum 27 © The Uniting Church in Australia Property Trust (Q.) Uniting Church guiding principles key 28 represented by Trinity College Queensland and the Schools and Residential Colleges Commission. Curriculum overview 29 Authors: Dr Paul Hedley Jones and Dr Daniel Pampuch Unit overview 32 This document is copyright. Schools that are owned, Units 40 operated or directly affiliated with The Uniting Church The Wesleyan quadrilateral 48 in Australia Property Trust (Q.) have permission to reproduce parts of the document as long as the original meaning is retained and proper credit is given Part C: Service learning 51 to The Uniting Church in Australia Property Trust Service learning 52 (Q.), represented by the Uniting Church in Australia, Queensland Synod. Purpose 52 All other persons and organisations that wish to A Uniting Church theology of service 53 reproduce material from this document will be required Uniting Church Agencies in Queensland 55 to obtain written permission from the publisher. -

Dialogue Australasian Network ST

Application Form Membership Application Form (Tax invoice) ABN 90 621 907 834) ST. MARY’S COLLEGE TAS PEMBROKE SCHOOL SA NAME PRINCE ALFRED COLLEGE SA ST. MICHAEL’S COLLEGIATE SCHOOL TAS PULTENEY GRAMMAR SCHOOL SA ST. PATRICK’S COLLEGE TAS SCHOOL/INSTITUTION ROSTREVOR COLLEGE SA ST. VIRGIL’S COLLEGE TAS SACRED HEART COLLEGE SENIOR SA THE DON COLLEGE TAS SACRED HEART COLLEGE MID SCH SA THE FRIENDS SCHOOL TAS ADDRESS SCOTCH COLLEGE ADELAIDE SA SEYMOUR COLLEGE SA NEW ZEALAND MEMBERS POST CODE SIENA COLLEGE SA BARADENE COLLEGE AUCKLAND SOUTHERN VALES CHN SCHOOL SA CARMEL COLLEGE AUCKLAND PHONE FAX SSABSA SA CATHOLIC INSTITUTE OF THEOLOGY AUCKALND Dialogue Australasian Network ST. ALOYSIUS COLLEGE SA CHRIST’S COLLEGE CHRISTCHURCH CONTACT PERSON The Dialogue Australasian Network is an exciting ST. ANNES SPECIAL SCHOOL SA CRAIGHEAD DIOCESAN SCHOOL TIMARU ST. DOMINIC’S PRIORY CLLGE SA DIOCESAN SCHOOL FOR GIRLS AUCKLAND POSITION and important initiative arising from the need ST. DOMINIC’S PRIORY CLLGE SA FRANCIS DOUGLAS MEM COL NEW PLYMOUTH to take values education more seriously in ST. FRANCIS DE DALES SA HAURAKI PLAINS COLLEGE NGATEA MEMBERSHIP CATAGORY (see below) Australasian schools. There are now well over 400 ST. IGNATIUS COLLEGE SA EVERITT AUCKLAND ST. IGNATIUS JUNIOR SCHOOL SA KING’S COLLEGE AUCKLAND EMAIL ADDRESS schools and organisations who are part of this ST. JOHN’S GRAMMAR SA KING’S SCHOOL AUCKLAND growing and vibrant network. Our aim is to help ST. JOHN’S GRAMMAR SCH SA KRISTIN SCHOOL ALBANY, AUCKLAND ST MARKS LUTHERAN SCHOOL SA Membership Categories our young people to become more fully human MARIAN COLLEGE CHRISTCHURCH Please note: DAN membership provides member schools and individuals with copies of the journal, cheap access ST. -

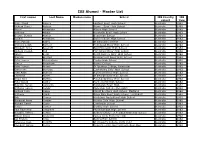

ISS Alumni - Master List

ISS Alumni - Master List First names Last Name Maiden name School ISS Country ISS cohort Year Brian David Aarons Fairfield Boys' High School Australia 1962 Richard Daniel Aldous Narwee Boys' High School Australia 1962 Alison Alexander Albury High School Australia 1962 Anthony Atkins Hurstville Boys' High School Australia 1962 George Dennis Austen Bega High School Australia 1962 Ronald Avedikian Enmore Boys' High School Australia 1962 Brian Patrick Bailey St Edmund's College Australia 1962 Anthony Leigh Barnett Homebush Boys' High School Australia 1962 Elizabeth Anne Beecroft East Hills Girls' High School Australia 1962 Richard Joseph Bell Fort Street Boys' High School Australia 1962 Valerie Beral North Sydney Girls' High School Australia 1962 Malcolm Binsted Normanhurst Boys' High School Australia 1962 Peter James Birmingham Casino High School Australia 1962 James Bradshaw Barker College Australia 1962 Peter Joseph Brown St Ignatius College, Riverview Australia 1962 Gwenneth Burrows Canterbury Girls' High School Australia 1962 John Allan Bushell Richmond River High School Australia 1962 Christina Butler St George Girls' High School Australia 1962 Bruce Noel Butters Punchbowl Boys' High School Australia 1962 Peter David Calder Hunter's Hill High School Australia 1962 Malcolm James Cameron Balgowlah Boys' High Australia 1962 Anthony James Candy Marcellan College, Randwich Australia 1962 Richard John Casey Marist Brothers High School, Maitland Australia 1962 Anthony Ciardi Ibrox Park Boys' High School, Leichhardt Australia 1962 Bob Clunas -

TRIALLING the Le@Rning Federation's LEARNING OBJECTS in SCHOOLS

Early-stage use of The Le@rning Federation’s learning objects in schools Results of a field review Peter Freebody January 2006 Contents Contents 2 Acknowledgements 3 Executive summary 4 Summary results 4 Next steps 4 The study 6 Introduction 6 Methods 9 Findings 11 Conclusions and ways forward 21 References 23 Appendix 1: Survey of students 24 Appendix 2: Survey of teachers 26 Appendix 3: Reports of case studies 31 Atherton State Primary School 31 Beechworth Primary School 35 Beverly Hills Intensive English Centre 38 Brighton Primary School 41 Distance Education School, Tasmania 44 Eclipse Centre, Canberra College 46 Good News Lutheran Primary School 50 Jingili Primary School 53 Kormilda College 55 Lowanna College 58 Mona Vale Public School 62 Monte Sant’Angelo Mercy College 65 New Town High School 68 Opunake High School 72 Southern Cross Campus (Middle School) 75 St Joseph’s Primary School, Hectorville 78 St Joseph’s School, Wyndham 81 Early-stage use of The Le@rning Federation’s learning objects in schools 2 Acknowledgements Author Peter Freebody is Professor of Education at the University of Queensland, and Academic Advisor to the Queensland Department of Education and the Arts. Consultants Sandy Muspratt and David McRae undertook most of the data collection and analysis. Sandy Muspratt is a postdoctoral research fellow at Griffith University, Queensland. David McRae is a research consultant based in Melbourne, Victoria. Participants The participation of principals, teachers, parents and students from the schools involved in the research is appreciated. Thanks are also expressed to The Le@rning Federation’s contact liaison officers who supported the research team in accessing data and information essential to the analysis reported.