Analysis and Research Into Co-Education in Australia and the UK and the Experience of Those Schools That Change Status

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Alliance Vol.20 Sept 01

in● lliance● THE ALLIANCE OF GIRLSa’SCHOOLS (AUSTRALASIA) LTD VOLUME 20 PO BOX 296, MALVERN, VICTORIA 3144 AUSTRALIA AUGUST 2001 in alliance The Alliance of Girls’ Schools (Australasia) Ltd Executive Director: Edwina Sear Tel: 03 9813 8916 Fax: 03 9886 9542 President: Ros Otzen Korowa AGS, Vic Executive: Beth Blackwood PLC, WA Santa Maria College: visual arts journey Lesley Boston The MacRobertson Girls’ High School, Vic Carolyn Hauff Clayfield College, Qld Nancy Hillier Annesley College, SA Suzanne McChesney Seymour College, SA Barbara Stone MLC, NSW Clayfield College: Artbox Program in this issue Queen Margaret College: designing dances ●● TheThe ArtsArts ●● TheThe JointJoint ConferenceConference ‘Equal‘Equal andand Different?’Different?’ Seymour College: a balancing act Main photo: Year 11 Textiles “Art Nouveau” from Santa Maria College In Alliance Editorial Deadline 2001 FROM THE EDITOR... Volume 21 “The Sciences” ... Alliance progress. Monday 15 October, 2001 Copy on the above topic for the relevant Volume is welcome Since our last edition of In Alliance, there has been Dr Jeannette Vos and Dr Paula Barrett for their roles in and must be submitted much activity. offering this inaugural Joint Conference topics which allowed both the boys’ and girls’ schools the opportunity to Dr Nancy Hillier The number of Alliance members has grown from 78 to muse the topic ‘Equal and Different?’ together. at Annesley College or when Edwina took over in November 2000 to 88 today. through We are looking forward to our membership growing As a single gender education conference, bringing [email protected] further. together boys’ and girls’ schools, we believe this is a world first, making the success of the conference more by the above date. -

The Following Schemes Are Used by Christian Heritage College (CHC) to Provide Adjustments to the Selection Ranks of Applicants T

The following schemes are used by Christian Heritage College (CHC) to provide adjustments to the selection ranks of applicants to CHC courses for admissions purposes: • CHC Partnership School Scheme; • CHC Community Engagement Scheme; and • Educational Access Scheme (EAS). Applicants must meet all other admission requirements for their preferred courses prior to the adjustments being applied. Only one scheme can be applied to an applicant’s selection rank. The requirements of the schemes, and the adjustments they provide, are explained below. Year 12 applicants can benefit from an adjustment of 2.00 selection ranks by completing Year 12 at a CHC Partner School (see Appendix 1). The CHC Community Engagement Scheme allows an adjustment of 2.00 selection ranks for applicants in CHC’s catchment area, according to their residential postcode (see Appendix 2). The Educational Access Scheme (EAS) allows an adjustment to be applied to the selection rank of applicants who have experienced difficult circumstances that have adversely impacted their studies. To be considered, applicants apply to QTAC for a confidential assessment of their circumstances. CRICOS Provider Name: Christian Heritage College CRICOS Provider No: 01016F The following are the schools to which the CHC Partnership School Scheme applies (as at July 2021): Greater Brisbane Area Regional Queensland Alta 1 College - Caboolture Bayside Christian College Hervey Bay (Urraween) Annandale Christian College Border Rivers Christian College (Goondiwindi) Arethusa College (Deception Bay Campus) -

10/12/2018 Barlow Park Athletics Centre Team Rankings

Licensed To: Athletics Australia-All Schools Champ - Organization License Hy-Tek's MEET MANAGER 1:08 PM 13/12/2018 Page 1 2018 Coles Nitro Schools Challenge National Final - 10/12/2018 Barlow Park Athletics Centre Team Rankings - Through Event 56 Female Team Scores - 2 Junior Girls Division Place Team Points 1 Pymble Ladies College PYMBL 900 2 St Aidan's Ags STAID 780 3 Haileybury HC 740 4 Nbsc Mackellar Girls Campus NBSC 720 5 All Hallows School Brisbane ALL H 650 6 Wesley College WESL 630 7 Moreton Bay College MBC 530 8 Presbyterian Ladies College PLC 490 9 Trinity College TRINS 460 10 Fairholme College FAIRH 450 11 Loreto Toorak LORET 340 Total 6,690.00 Female Team Scores - 4 Intermediate Girls Division Place Team Points 1 Pymble Ladies College PYMBL 1,005 2 Moreton Bay College MBC 875 3 Caulfield Grammar School CAULF 750 4 King's Christian College KING' 650 5 Abbotsleigh ABBOT 590 6 Loreto Toorak LORET 550 7 Presbyterian Ladies College PLC 530 8 Frankston High School FHS 500 9 Canterbury College CANT 480 10 Latrobe High School LATH 240 Total 6,170.00 Female Team Scores - 6 Senior Girls Division Place Team Points 1 Stella Maris STELL 690 2 Pymble Ladies College PYMBL 600 3 Wesley College WESL 595 4 Sheldon College SHELD 590 5 Mt St Michael's College MT ST 555 6 The Glennie School THE G 510 7 Abbotsleigh ABBOT 410 8 Trinity College TRINS 290 Total 4,240.00 Male Team Scores - 1 Junior Boys Division Place Team Points 1 Haileybury HC 750 2 Trinity Grammar School TRINI 710 3 Brisbane Boys College BRISB 700 4 Melbourne Grammar School MGS -

31/08/2018 1 of 8 ROSTRUM VOICE of YOUTH NATIONAL FINALISTS

ROSTRUM VOICE OF YOUTH NATIONAL FINALISTS Year Nat Final Convenor Zone Coordinator Junior Finalist School Place Senior Finalist School Place National Coordinator 1975 Tom Trebilco ACT Tom Trebilco Fiona Tilley Belconnen HS 1 Linzi Jones 1975 NSW 1975 QLD Vince McHugh Sue Stevens St Monica's College Cairns Michelle Barker 1975 SA NA NA NA Sheryn Pitman Methodist Ladies College 2 1975 TAS Mac Blackwood Anthony Ackroyd St Virgils College, Hobart 1 1975 VIC 1975 WA Year Nat Final Convenor Zone Coordinator Junior Finalist School Place Senior Finalist School Place 1976 Tom Trebilco? ACT Tom Trebilco? Tim Hayden Telopea Park HS 1 (tie) 1976 NSW 1976 QLD Vince McHugh Michelle Morgan Brigadine Convent Margaret Paton All Hallows School Brisbane 1976 SA NA NA NA NA NA 1976 TAS Mac Blackwood Lisa Thompson Oakburn College 1 (tie) 1976 VIC 1976 WA Paul Donovan St Louis School 1 Year Nat Final Convenor Zone Coordinator Junior Finalist School Place Senior Finalist School Place 1977 ACT Michelle Regan (sub) Belconnen HS 1977 NSW John White Kerrie Mengerson Coonabarabran HS 1 Sonia Anderson Francis Greenway HS,Maitland 1 1977 QLD Mervyn Green Susan Burrows St Margarets Clayfield Anne Frawley Rockhampton 1977 SA NA NA NA NA NA 1977 TAS Mac Blackwood Julie Smith Burnie High Gabrielle Bennett Launceston 1977 Richard Smillie VIC Pat Taylor Linda Holland St Anne's Warrnambool 3 Kelvin Bicknell Echuca Technical 1977 WA David Johnston Mark Donovan John XX111 College 2 Fiona Gauntlett John XX111 College 2 Year Nat Final Convenor Zone Coordinator Junior Finalist -

Annual Report 2012

Board of Trustees Brisbane Grammar School Annual Report 2012 ISSN 1837-8722 2012 TABLE OF CONTENTS 1. CONSTITUTION, GOALS AND FUNCTIONS ............................................................. 1 2. LOCATION ...................................................................................................................... 4 3. STRUCTURES ................................................................................................................. 5 4. REVIEW OF THE PROGRESS IN ACHIEVING THE BOARD OF TRUSTEES STATUTORY OBLIGATIONS ....................................................................................... 6 5. SUMMARY OF SIGNIFICANT OPERATIONS ............................................................ 6 6. REVIEW OF PROGRESS TOWARDS ACHIEVING GOALS AND DELIVERING OUTCOMES ................................................................................................................... 16 7. PROPOSED FORWARD OPERATIONS ..................................................................... 19 8. FINANCIAL OPERATIONS AND EFFECTIVENESS ................................................ 20 9. SYSTEMS FOR OBTAINING INFORMATION ABOUT FINANCIAL AND OPERATIONAL PERFORMANCE .............................................................................. 21 10. RISK MANAGEMENT .................................................................................................. 22 11. CARERS (RECOGNITION) ACT 2008 ........................................................................ 23 12. PUBLIC SECTOR ETHICS ACT 1994 ........................................................................ -

Answers to Questions on Notice

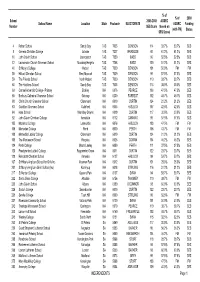

% of % of 2008 School 2005-2008 AGSRC School Name Location State Postcode ELECTORATE AGSRC Funding Number SES Score (based on (with FM) Status SES Score) 4 Fahan School Sandy Bay TAS 7005 DENISON 114 33.7% 33.7% SES 5 Geneva Christian College Latrobe TAS 7307 BRADDON 92 61.2% 61.2% SES 10 John Calvin School Launceston TAS 7250 BASS 99 52.5% 52.5% SES 12 Launceston Church Grammar School Mowbray Heights TAS 7248 BASS 100 51.2% 51.2% SES 40 St Mary's College Hobart TAS 7000 DENISON 101 50.0% FM FM 55 Hilliard Christian School West Moonah TAS 7009 DENISON 95 57.5% 57.5% SES 59 The Friends School North Hobart TAS 7000 DENISON 110 38.7% 38.7% SES 60 The Hutchins School Sandy Bay TAS 7005 DENISON 113 35.0% 35.0% SES 63 Carmel Adventist College - Primary Bickley WA 6076 PEARCE 103 47.5% 47.5% SES 65 Bunbury Cathedral Grammar School Gelorup WA 6230 FORREST 102 48.7% 48.7% SES 68 Christ Church Grammar School Claremont WA 6010 CURTIN 124 21.2% 21.2% SES 83 Guildford Grammar School Guildford WA 6055 HASLUCK 107 42.5% 42.5% SES 84 Hale School Wembley Downs WA 6019 CURTIN 117 30.0% 30.0% SES 92 John Calvin Christian College Armadale WA 6112 CANNING 95 57.5% 57.5% SES 105 Mazenod College Lesmurdie WA 6076 HASLUCK 103 47.5% FM FM 106 Mercedes College Perth WA 6000 PERTH 106 43.7% FM FM 108 Methodist Ladies' College Claremont WA 6010 CURTIN 124 21.2% 21.2% SES 109 The Montessori School Kingsley WA 6026 COWAN 104 46.2% 46.2% SES 124 Perth College Mount Lawley WA 6050 PERTH 111 37.5% 37.5% SES 126 Presbyterian Ladies' College Peppermint Grove WA 6011 CURTIN -

Tasmanian Primary All Schools XC 2019 10 Years Girls June 25, 2019

Tasmanian Primary All Schools XC_2019 10 Years Girls June 25, 2019 Place Name Team Bib Number Total Time 1 ZAHLI WESCOMBE STELLA MARIS CATHOLIC SCHOOL 487 7:48 2 VIOLET OWEN ST MICHAEL'S COLLEGIATE SCHOOL 315 7:55 3 ANNABELLE COOK WEST LAUNCESTON PRIMARY SCHOOL 211 8:15 4 MATILDA LANGE CALVIN CHRISTIAN SCHOOL 509 8:18 5 MAYA DAVIES SACRED HEART CATHOLIC SCHOOL (ULVERSTONE)1110 8:20 6 ALEXANDRA ELLIOTT BRACKNELL PRIMARY SCHOOL 6 8:22 7 INIKA BARNES STELLA MARIS CATHOLIC SCHOOL 488 8:29 8 MELALEUCA BESTLEY- TOMANSOUTH HOBART PRIMARY SCHOOL 1122 8:35 9 BESSY BRERETON ST ALOYSIUS CATHOLIC COLLEGE 161 8:35 10 RUBY JONES SACRED HEART SCHOOL (LAUNCESTON) 120 8:36 11 RUBY LEDITSCHKE MARGATE PRIMARY SCHOOL 415 8:38 12 GEORGIA CAREY ST LEONARDS PRIMARY SCHOOL 864 8:38 13 EVA BERMUDES ENESSA 741 8:39 14 AMBER MCMULLAN PORT DALRYMPLE SCHOOL 772 8:40 15 MACIE PETTERWOOD ST THOMAS MORE'S CATHOLIC SCHOOL 468 8:41 16 ARLIE STAVELEY STELLA MARIS CATHOLIC SCHOOL 490 8:43 17 EDIE TRACEY LENAH VALLEY PRIMARY SCHOOL 675 8:50 18 PAIGE SPRINGER ENESSA 747 8:50 19 TARA SCIBERRAS FAHAN SCHOOL 23 8:50 20 GRACE BURBURY ST MICHAEL'S COLLEGIATE SCHOOL 308 8:56 21 MIA KRUSE LAUDERDALE PRIMARY SCHOOL 409 8:58 22 TESS STANSFIELD LENAH VALLEY PRIMARY SCHOOL 1041 8:58 23 JEMIMA BURBURY ST MICHAEL'S COLLEGIATE SCHOOL 313 8:59 24 ESTELLE NICHOLAS LINDISFARNE NORTH PRIMARY SCHOOL 411 9:00 25 LILY MATTHEWS SACRED HEART SCHOOL (LAUNCESTON) 116 9:01 26 ISABELLA COSTA ST THERESE'S CATHOLIC SCHOOL 900 9:01 27 IMOGEN SWARD HOWRAH PRIMARY SCHOOL 249 9:01 28 STELLA RILEY ST PATRICK'S -

Ipswich Grammar School International Student Handbook

Ipswich Grammar School International Student Handbook Board of Trustees of the Ipswich Grammar School Trading as Ipswich Grammar School CRICOS Provider Number: 00499A Table of Contents 1. Introduction .................................................................................................................................................................................... 4 2. Mission Statement ........................................................................................................................................................................ 4 3. Procedure for Enrolment ............................................................................................................................................................ 4 4. Fees ..................................................................................................................................................................................................... 5 5. Policy on Entry Requirements .................................................................................................................................................. 5 6. Course Credit .................................................................................................................................................................................. 9 7. Sport & Activities .......................................................................................................................................................................... 9 8. Uniforms .......................................................................................................................................................................................... -

Independent Schools Scholarships & Bursaries2018

INDEPENDENT SCHOOLS SCHOLARSHIPS & BURSARIES 2018 Everything you need to know about scholarships and bursaries starts here IN THIS Why choose an independent education? ISSUE 6 helpful tips to make the most of your scholarship application experience PARTICIPATING SCHOOLS (select a school) All Saints College Redlands All Saints Grammar Roseville College Arden Anglican School Rouse Hill Anglican College Ascham School Santa Sabina College Blue Mountains Grammar School SCEGGS Darlinghurst Brigidine College - St Ives Sydney Church of England Frensham School Grammar School (Shore) Hills Grammar St Andrew’s Cathedral School Inaburra School St Catherine’s School - Waverley International Grammar School St Joseph’s College Kambala St Luke’s Grammar School Kinross Wolaroi School St Spyridon College Macarthur Anglican School Tara Anglican School For Girls MLC School The Armidale School (TAS) Monte Sant’ Angelo Mercy College The King’s School Newington College The McDonald College Our Lady of Mercy College Trinity Grammar School Presbyterian Ladies’ College Sydney Wenona School Ravenswood KAMBALA GIRLS SCHOOL ROSE BAY www.kambala.nsw.edu.au Kambala is an Anglican, independent day and boarding school for girls located on the rising shore above Rose Bay with a breathtaking view of Sydney Harbour. Founded in 1887, Kambala caters for students from Preparation to Year 12, with boarders generally entering the School from Year 7. Kambala offers a broad and holistic education and the opportunity for students to truly excel. Kambala’s rich and varied programs, administered in a positive and supportive environment, inspire every student to realise her own purpose with integrity, passion and generosity. Kambala aspires to raise leaders of the future who are academically curious and intellectually brave. -

Annual Report 2019

Annual Report 2019 2 2019 Annual Report Brisbane Grammar School Interpretation Requests Brisbane Grammar School is committed to providing accessible services to people from all culturally and linguistically diverse backgrounds. Please provide any feedback, interpreter requests, copyright requests or suggestions to the Deputy Headmaster – Staff at the undernoted address. Report Availability This report is available for viewing by contacting the Deputy Headmaster – Staff. Brisbane Grammar School Tel (07) 3834 5200 Fax (07) 3834 5202 Email [email protected] Website www.brisbanegrammar.com Online www.brisbanegrammar.com/About/Reporting/ ISSN: 1837-8722 © (Board of Trustees of the Brisbane Grammar School), 2020 Brisbane Grammar School 2019 Annual Report 3 LETTER OF COMPLIANCE 4 2019 Annual Report Brisbane Grammar School Table of Contents Letter of Compliance 4 SECTION A GOVERNANCE REPORT 6 About the School 7 Locations 7 Legislative bases 8 Values and ethics 8 Leadership 9 Senior Leadership Team 15 Statutory Requirements 18 Risk management 18 Audit 18 External scrutiny 18 Record keeping 20 SECTION B STRATEGY REPORT 22 From the Chair 23 From the Headmaster 25 Strategic Intent 2018 – 2022 28 2019 In Review 36 Enrolments 36 Academic 39 Student wellbeing 43 Co-Curriculum 46 Staff 49 Advancement and Community Relations 52 Infrastructure 54 Finance 55 SECTION C APPENDICES 57 Open Data 56 Consultancies 58 Overseas travel 58 Financial Statements 59 Glossary 95 Compliance Checklist 99 Brisbane Grammar School 2019 Annual Report 5 Section A Governance Report 6 2019 Annual Report Brisbane Grammar School ABOUT THE SCHOOL Locations Spring Hill Campus Brisbane Grammar School provides education programs on five campuses. The main campus of nearly eight hectares is on Gregory Terrace overlooking the Brisbane CBD and is the site for the delivery of the main academic program across Years 5 to 12, as well as the Indoor Sports Centre and boarding house. -

Results Day 7

Race 549 Event 70 07:45 Sun, 11 Mar 2007 Distance 2000m Champion Schoolgirls Single Scull Removed Pl Crew# Crew Name Lane 500 1000 1500 2000 Race 550 Event 70 07:50 Sun, 11 Mar 2007 Distance 2000m Champion Schoolgirls Single Scull Final 8 Pl Crew# Crew Name Lane 500 1000 1500 2000 1 70:25 Melbourne Girls College 6 2:13.37 (1) 4:35.88 (1) 6:54.68 (1) 9:09.42 (1) Kennedy 2:22.51 (1) 2:18.80 (1) 2:14.74 (2) 2 70:20 John Curtin Senior High School 3 2:14.07 (2) 4:36.65 (2) 6:59.47 (2) 9:23.10 (2) Kekez 0.70 0.77 4.79 13.68 2:22.58 (2) 2:22.82 (2) 2:23.63 (3) 3 70:42 Somerset College 5 2:16.59 (3) 4:45.35 (3) 7:20.67 (4) 9:32.64 (3) DAVIS 3.22 9.47 25.99 23.22 2:28.76 (4) 2:35.32 (4) 2:11.97 (1) 4 70:26 Mercedes College 4 2:18.27 (4) 4:45.71 (4) 7:17.95 (3) 9:45.88 (4) Marryat 4.90 9.83 23.27 36.46 2:27.44 (3) 2:32.24 (3) 2:27.93 (4) 5 70:28 MLC School 2 2:25.96 (5) 5:03.47 (5) 7:43.90 (5) 10:17.22 (5) Crossley 12.59 27.59 49.22 1:07.80 2:37.51 (5) 2:40.43 (5) 2:33.32 (5) Race 551 Event 70 07:55 Sun, 11 Mar 2007 Distance 2000m Champion Schoolgirls Single Scull Final 7 Pl Crew# Crew Name Lane 500 1000 1500 2000 1 70:52 The Friends School 5 2:01.17 (1) 4:20.03 (1) 6:39.32 (1) 8:54.30 (1) Beasley 2:18.86 (1) 2:19.29 (3) 2:14.98 (5) 2 70:16 Grafton High School 2 2:07.40 (2) 4:27.43 (2) 6:45.98 (2) 9:00.09 (2) Jones 6.23 7.40 6.66 5.79 2:20.03 (2) 2:18.55 (2) 2:14.11 (3) 3 70:17 Iona Presentation College 3 2:08.73 (3) 4:30.32 (3) 6:47.88 (3) 9:00.46 (3) Westbrook 7.56 10.29 8.56 6.16 2:21.59 (5) 2:17.56 (1) 2:12.58 (2) 4 70:10 Canberra Rowing Club -

Curriculum Vitae: Zischke Page| 1

Curriculum Vitae: Zischke Page| 1 Dr. Mitchell Thomas Zischke Department of Forestry and Natural Resources, Purdue University 195 Marsteller St, West Lafayette, IN, 47906, United States Phone: +1 (765) 494-9717; Email: [email protected] CURRENT POSITIONS 2017-current: Clinical Assistant Professor in Fisheries and Aquatic Sciences Purdue University Department of Forestry and Natural Resources Teaching activities include instructing marine biology, fish ecology and fisheries management courses, as well as numerous guest lectures. Advisory activities include supervising undergraduate and graduate students, as well as advising the Purdue chapter of the American Fisheries Society and the Purdue Bass Fishing club. Extension is collaborative with the Illinois-Indiana Sea Grant and include programs on recreational fisheries in Lake Michigan and pond management throughout the Midwest. EDUCATION 2008- 2013: Doctor of Philosophy (PhD) in Fisheries Science The University of Queensland, Brisbane QLD Australia CSIRO Marine & Atmospheric Research, Brisbane, Australia Degree awarded on July 4, 2013 2006: Bachelor of Science (BSc) with Honors (Hons.) Honors Class 1 in the field of Parasitology Grade Point Average: 7.0/7 The University of Queensland, Brisbane QLD Australia 2002-2005: Bachelor of Science (BSc) Major in Tropical Marine Science 3rd Year Grade Point Average: 5.6/7 The University of Queensland, Brisbane QLD Australia 1997-2001: High School Senior Certificate Overall Position (OP): 4 Ipswich Grammar School, Ipswich QLD Australia PUBLICATIONS I have published 14 peer-reviewed journal articles, 2 theses, 5 final reports and 9 extension products. My work has been cited 198 times and my h-index is 10. 1. Griffiths, S.P., Zischke, M.T., van der Velde, T., Fry, G.C.