Anaesthetic Experience with Paediatric Interventional Cardiology

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Product Monograph Vecuronium Bromide For

PRODUCT MONOGRAPH PrVECURONIUM BROMIDE FOR INJECTION Non-depolarizing Skeletal Neuromuscular Blocking Agent Pharmaceutical Partners of Canada Inc. Date of Preparation: 45 Vogell Road, Suite 200 January 15, 2008 Richmond Hill, ON L4B 3P6 Control No.: 119276 PRODUCT MONOGRAPH PrVECURONIUM BROMIDE FOR INJECTION Non-depolarizing Skeletal Neuromuscular Blocking Agent THIS DRUG SHOULD BE ADMINISTERED ONLY BY ADEQUATELY TRAINED INDIVIDUALS FAMILIAR WITH ITS ACTIONS, CHARACTERISTICS AND HAZARDS ACTIONS AND CLINICAL PHARMACOLOGY Vecuronium Bromide for Injection is a non-depolarizing neuromuscular blocking agent of intermediate duration possessing all of the characteristic pharmacological actions of this class of drugs (curariform). It acts by competing for cholinergic receptors at the motor end-plate. The antagonism to acetylcholine is inhibited and neuromuscular block reversed by acetylcholinesterase inhibitors such as neostigmine. Vecuronium Bromide for Injection is about 1/3 more potent than pancuronium; the duration of neuromuscular blockade produced by Vecuronium Bromide for Injection is shorter than that of pancuronium at initially equipotent doses. The time to onset of paralysis decreases and the duration of maximum effect increases with increasing Vecuronium Bromide for Injection doses. The use of a peripheral nerve stimulator is of benefit in assessing the degree of muscular relaxation. The ED90 (dose required to produce 90% suppression of the muscle twitch response with balanced anesthesia) has averaged 0.057 mg/kg (0.049 to 0.062 mg/kg in various studies). An initial Vecuronium Bromide for Injection dose of 0.08 to 0.10 mg/kg generally produces first depression of twitch in approximately 1 minute, good or excellent intubation conditions within 2.5 to 3 minutes, and maximum neuromuscular blockade within 3 to 5 minutes of injection in Vecuronium Bromide for Injection, Product Monograph Page 2 of 28 most patients. -

BRS Pharmacology

Pharmacology Gary C. Rosenfeld, Ph.D. Professor Department of Integrated Biology and Pharmacology and Graduate School of Biomedical Sciences Assistant Dean for Education Programs University of Texas Medical School at Houston Houston, Texas David S. Loose, Ph.D. Associate Professor Department of Integrated Biology and Pharmacology and Graduate School of Biomedical Sciences University of Texas Medical School at Houston Houston, Texas With special contributions by Medina Kushen, M.D. William Beaumont Hospital Royal Oak, Michigan Todd A. Swanson, M.D., Ph.D. William Beaumont Hospital Royal Oak, Michigan Acquisitions Editor: Charles W. Mitchell Product Manager: Stacey L. Sebring Marketing Manager: Jennifer Kuklinski Production Editor: Paula Williams Copyright C 2010 Lippincott Williams & Wilkins 351 West Camden Street Baltimore, Maryland 21201-2436 USA 530 Walnut Street Philadelphia, PA 19106 All rights reserved. This book is protected by copyright. No part of this book may be reproduced in any form or by any means, including photocopying, or utilized by any information storage and retrieval system without written permission from the copyright owner. The publisher is not responsible (as a matter of product liability, negligence or otherwise) for any injury resulting from any material contained herein. This publication contains information relating to general principles of medical care which should not be construed as specific instructions for individual patients. Manufacturers’ product information and package inserts should be reviewed for current information, including contraindications, dosages and precautions. Printed in the United States of America Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Rosenfeld, Gary C. Pharmacology / Gary C. Rosenfeld, David S. Loose ; with special contributions by Medina Kushen, Todd A. -

Doxacurium Chloride Injection Abbott Laboratories

NUROMAX - doxacurium chloride injection Abbott Laboratories ---------- NUROMAX® (doxacurium chloride) Injection This drug should be administered only by adequately trained individuals familiar with its actions, characteristics, and hazards. NOT FOR USE IN NEONATES CONTAINS BENZYL ALCOHOL DESCRIPTION NUROMAX (doxacurium chloride) is a long-acting, nondepolarizing skeletal muscle relaxant for intravenous administration. Doxacurium chloride is [1α,2β(1'S*,2'R*)]-2,2' -[(1,4-dioxo-1,4- butanediyl)bis(oxy-3,1-propanediyl)]bis[1,2,3,4-tetrahydro-6,7,8-trimethoxy-2- methyl-1-[(3,4,5- trimethoxyphenyl)methyl]isoquinolinium] dichloride (meso form). The molecular formula is C56H78CI2N2O16 and the molecular weight is 1106.14. The compound does not partition into the 1- octanol phase of a distilled water/ 1-octanol system, i.e., the n-octanol:water partition coefficient is 0. Doxacurium chloride is a mixture of three trans, trans stereoisomers, a dl pair [(1R,1'R ,2S,2'S ) and (1S,1'S ,2R,2'R )] and a meso form (1R,1'S,2S,2'R). The meso form is illustrated below: NUROMAX Injection is a sterile, nonpyrogenic aqueous solution (pH 3.9 to 5.0) containing doxacurium chloride equivalent to 1 mg/mL doxacurium in Water for Injection. Hydrochloric acid may have been added to adjust pH. NUROMAX Injection contains 0.9% w/v benzyl alcohol. Reference ID: 2867706 CLINICAL PHARMACOLOGY NUROMAX binds competitively to cholinergic receptors on the motor end-plate to antagonize the action of acetylcholine, resulting in a block of neuromuscular transmission. This action is antagonized by acetylcholinesterase inhibitors, such as neostigmine. Pharmacodynamics NUROMAX is approximately 2.5 to 3 times more potent than pancuronium and 10 to 12 times more potent than metocurine. -

Atracurium Besylate Injection

PRODUCT MONOGRAPH PrATRACURIUM BESYLATE INJECTION 10 mg/mL Skeletal Neuromuscular Blocking Agent Sandoz Canada Inc. Date of Revision: March 25, 2013 145 Jules-Léger Boucherville, QC, Canada J4B 7K8 Control no.: 161881 Atracurium Besylate Injection Page 1 of 19 PrATRACURIUM BESYLATE INJECTION 10 mg/mL THERAPEUTIC CLASSIFICATION Skeletal Neuromuscular Blocking Agent ACTIONS AND CLINICAL PHARMACOLOGY Atracurium besylate is a nondepolarizing, intermediate-duration, skeletal neuromuscular blocking agent. Nondepolarizing agents antagonize the neurotransmitter action of acetylcholine by binding competitively to cholinergic receptor sites on the motor end-plate. This antagonism is inhibited, and neuromuscular block reversed, by acetylcholinesterase inhibitors such as neostigmine, edrophonium and pyridostigmine. The duration of neuromuscular blockade produced by atracurium besylate is approximately one-third to one-half the duration seen with d-tubocurarine, metocurine and pancuronium at equipotent doses. As with other nondepolarizing neuromuscular blockers, the time to onset of paralysis decreases and the duration of maximum effect increases with increasing atracurium besylate doses. The pharmacokinetics of atracurium besylate in man are essentially linear within the 0.3 to 0.6 mg/kg dose range. The elimination half-life is approximately 20 minutes. The duration of neuromuscular blockade does not correlate with plasma pseudocholinesterase levels and is not altered by the absence of renal function. INDICATIONS AND CLINICAL USE Atracurium Besylate Injection is indicated, as an adjunct to general anaesthesia, to facilitate endotracheal intubation and to provide skeletal muscle relaxation during surgery or mechanical ventilation. It can be used most advantageously if muscle twitch response to peripheral nerve stimulation is monitored. CONTRAINDICATIONS Atracurium besylate is contraindicated in patients known to have a hypersensitivity to it. -

(12) Patent Application Publication (10) Pub. No.: US 2010/009874.6 A1 King (43) Pub

US 201000987.46A1 (19) United States (12) Patent Application Publication (10) Pub. No.: US 2010/009874.6 A1 King (43) Pub. Date: Apr. 22, 2010 (54) COMPOSITIONS AND METHODS FOR Related U.S. Application Data TREATING PERIODONTAL DISEASE COMPRISING CLONDINE, SULINDAC (60) Provisional application No. 61/106,815, filed on Oct. AND/OR FLUOCNOLONE 20, 2008. Publication Classification (75) Inventor: Vanja Margareta King, Memphis, TN (US) (51) Int. Cl. A6F I3/00 (2006.01) Correspondence Address: A6II 3/56 (2006.01) MEDTRONIC (52) U.S. Cl. ......................................... 424/435: 514/171 Attn: Noreen Johnson - IP Legal Department (57) ABSTRACT 2600 Sofamor Danek Drive MEMPHIS, TN38132 (US) Effective treatments of periodontal disease for extended peri ods of time are provided. Through the administration of an (73) Assignee: Warsaw Orthopedic, Inc., Warsaw, effective amount of clonidine, Sulindac, and/or fluocinolone IN (US) at or near a target site, one can reduce, prevent, and/or treat periodontal disease. In some embodiments, when appropriate (21) Appl. No.: 12/572,387 formulations are provided within biodegradable polymers, treatment can be continued for at least two weeks to two (22) Filed: Oct. 2, 2009 months. Patent Application Publication Apr. 22, 2010 Sheet 1 of 3 US 2010/009874.6 A1 FIG. 1 Clonidine 15 o 9. 10 wd O O 2 SS 5 O RANK Control 100 M 10 M M 0.1 LM Concentration Patent Application Publication Apr. 22, 2010 Sheet 2 of 3 US 2010/009874.6 A1 FIG. 2 Sulindac 5 1 O RANK Control 70 M 35M 7.5 M ConCentration Patent Application Publication Apr. -

Overall Educational Goal of Elective the Goal of This Rotation Is to Enable

Overall Educational Goal of Elective The goal of this rotation is to enable students to better understand the risks and hazards of anesthesia, so that they can learn to safely prepare a patient physically and emotionally for the operating room. Students will also become familiar with problems specific to anesthesia, so that they will be able to consult with the anesthesiologist regarding medical problems that may affect the patient’s response to anesthesia and surgery. In the process, students will learn what it means for a patient to be in the most optimal condition before proceeding to the operating room. Objectives • To give students an appreciation of the field of Anesthesiology • To teach techniques of preoperative evaluation and the implications of concurrent medical conditions in the intraoperative period • To teach the characteristics of commonly used anesthetic agents and techniques and their risks and complications • To acquaint students with the principles and skills involved in airway management, intravenous line insertion, and the use of invasive and non-invasive monitoring Brief Description of Activities Students will participate in the induction of anesthesia and the maintenance of an airway by both mask and intubation; intraoperative management including the use of various anesthetic agents; various regional anesthetic techniques; pain management for acute and chronic conditions; the anesthetic management of the obstetrical, cardiac and pediatric patient; and anesthetic goals in an ambulatory setting. Methods of Student Evaluation Students will be assigned to an anesthesia attending and resident who will be responsible for evaluating their progress. Evaluation will be done by observing the students involvement in the intraoperative management of the patients that they are following and their ability to handle simple anesthetic techniques. -

Reversal of Neuromuscular Bl.Pdf

JosephJoseph F.F. Answine,Answine, MDMD Staff Anesthesiologist Pinnacle Health Hospitals Harrisburg, PA Clinical Associate Professor of Anesthesiology Pennsylvania State University Hospital ReversalReversal ofof NeuromuscularNeuromuscular BlockadeBlockade DefiniDefinitionstions z ED95 - dose required to produce 95% suppression of the first twitch response. z 2xED95 – the ED95 multiplied by 2 / commonly used as the standard intubating dose for a NMBA. z T1 and T4 – first and fourth twitch heights (usually given as a % of the original twitch height). z Onset Time – end of injection of the NMBA to 95% T1 suppression. z Recovery Time – time from induction to 25% recovery of T1 (NMBAs are readily reversed with acetylcholinesterase inhibitors at this point). z Recovery Index – time from 25% to 75% T1. PharmacokineticsPharmacokinetics andand PharmacodynamicsPharmacodynamics z What is Pharmacokinetics? z The process by which a drug is absorbed, distributed, metabolized and eliminated by the body. z What is Pharmacodynamics? z The study of the action or effects of a drug on living organisms. Or, it is the study of the biochemical and physiological effects of drugs. For example; rocuronium reversibly binds to the post synaptic endplate, thereby, inhibiting the binding of acetylcholine. StructuralStructural ClassesClasses ofof NondepolarizingNondepolarizing RelaxantsRelaxants z Steroids: rocuronium bromide, vecuronium bromide, pancuronium bromide, pipecuronium bromide. z Benzylisoquinoliniums: atracurium besylate, mivacurium chloride, doxacurium chloride, cisatracurium besylate z Isoquinolones: curare, metocurine OnsetOnset ofof paralysisparalysis isis affectedaffected by:by: z Dose (relative to ED95) z Potency (number of molecules) z KEO (plasma equilibrium constant - chemistry/blood flow) — determined by factors that modify access to the neuromuscular junction such as cardiac output, distance of the muscle from the heart, and muscle blood flow (pharmacokinetic variables). -

Anesthesia Labels & Tape

Anesthesia Labels & Tape PDC Healthcare’s Anesthesia Labels & Tape help address errors caused by the use of unlabeled medications and other procedural breakdowns that can put patients at risk. They adhere to specific guidelines set forth by The Joint Commission, United States Pharmacopoeia (USP), and the American Society for Testing and Materials (ASTM), including: 1. Specific color and format standards for each drug class 2. Appropriate information on each tape/label (drug name, strength, amount, date, time, initials) 3. TALLman lettering to clearly differentiate common look-alike, sound-alike drugs 4. Tape and labels with standard pre-printed concentrations Our stock, pre-printed Anesthesia Tape and Table of Contents Labels help increase patient safety by delivering Anesthesia Labels & Tapes ........................................80 higher accuracy in medication administration. If you do not see the anesthesia products needed Anesthesia Labels & Tapes Custom ....................86 for your facility, PDC Healthcare can customize Dispensers................................................................................86 any tape or label with the desired information. Anesthesia Tape & Labels help healthcare organizations meet applicable patient safety regulatory guidelines, including: ■ The Joint Commission National Patient Safety Goals: Identify Patients Correctly, Improve Staff Communication, Use Medicines Safely, Prevent Infection, Identify Patient Safety Risks, and Prevent Mistakes in Surgery. ■ Five Rights of Patient Safety: to ensure right patient, medication, dose, time, and method. CALL 800.435.4242 | FAX 800.321.4409 www.pdchealthcare.com 79 ANESTHESIA ANESTHESIA LABELS & TAPE ALPHABETICALLY LISTED The following stock drug tapes and labels are available for accurate and reliable labeling of all anesthesia drug syringes. Each tape/label conforms to the nationally recognized ASTM Standard D4774-94(2000) Specification for User Applied Drug Labels in Anesthesiology. -

Newborn Anaesthesia: Pharmacological Considerations D

$38 REFRESHER COURSE OUTLINE Newborn anaesthesia: pharmacological considerations D. Ryan Cook MD Inhalation anaesthetics Several investigators have studied the age-related For the inhalation anaesthetics there are age-related cardiovascular effects of the potent inhalation differences in uptake and distribution, in anaes- anaesthetics at known multiples of MAC. At thetic requirements as reflected by differences in end-tidal concentrations of halothane bracketing MAC, in the effects on the four determinants of MAC, Lerman er al. 2 noted no difference in the cardiac output (preload, afterload, heart rate and incidence of hypotension or bradycardia in neonates contractility), and in the sensitivity of protective and in infants one to six months of age. Likewise, cardiovascular reflexes (e.g., baroreceptor reflex). we 3 have noted no age-related differences in the These differences limit the margin of safety of the determinants of cardiac output in developing piglets potent agents in infants. 1-20 days during either halothane or isoflurane Alveolar uptake of inhalation anaesthetics and anaesthesia. Halothane produced hypotension by a hence whole-body uptake is more rapid in infants reduction in contractility and heart rate; in much than in adults. J Lung washout is more rapid in older animals halothane also decreases peripheral infants than in adults because of the larger ratio vascular resistance. In piglets although blood pres- between alveolar minute ventilation and lung sure was equally depressed with isoflurane and volume (FRC) (3.5:1 in the infant vs. 1.3:1 in the halothane, cardiac output was better preserved adult). Increased brain size (ml.kg-J), limited during isoflurane anaesthesia. -

Drug and Medication Classification Schedule

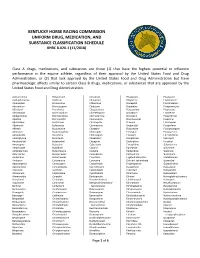

KENTUCKY HORSE RACING COMMISSION UNIFORM DRUG, MEDICATION, AND SUBSTANCE CLASSIFICATION SCHEDULE KHRC 8-020-1 (11/2018) Class A drugs, medications, and substances are those (1) that have the highest potential to influence performance in the equine athlete, regardless of their approval by the United States Food and Drug Administration, or (2) that lack approval by the United States Food and Drug Administration but have pharmacologic effects similar to certain Class B drugs, medications, or substances that are approved by the United States Food and Drug Administration. Acecarbromal Bolasterone Cimaterol Divalproex Fluanisone Acetophenazine Boldione Citalopram Dixyrazine Fludiazepam Adinazolam Brimondine Cllibucaine Donepezil Flunitrazepam Alcuronium Bromazepam Clobazam Dopamine Fluopromazine Alfentanil Bromfenac Clocapramine Doxacurium Fluoresone Almotriptan Bromisovalum Clomethiazole Doxapram Fluoxetine Alphaprodine Bromocriptine Clomipramine Doxazosin Flupenthixol Alpidem Bromperidol Clonazepam Doxefazepam Flupirtine Alprazolam Brotizolam Clorazepate Doxepin Flurazepam Alprenolol Bufexamac Clormecaine Droperidol Fluspirilene Althesin Bupivacaine Clostebol Duloxetine Flutoprazepam Aminorex Buprenorphine Clothiapine Eletriptan Fluvoxamine Amisulpride Buspirone Clotiazepam Enalapril Formebolone Amitriptyline Bupropion Cloxazolam Enciprazine Fosinopril Amobarbital Butabartital Clozapine Endorphins Furzabol Amoxapine Butacaine Cobratoxin Enkephalins Galantamine Amperozide Butalbital Cocaine Ephedrine Gallamine Amphetamine Butanilicaine Codeine -

Pharmaceuticals As Environmental Contaminants

PharmaceuticalsPharmaceuticals asas EnvironmentalEnvironmental Contaminants:Contaminants: anan OverviewOverview ofof thethe ScienceScience Christian G. Daughton, Ph.D. Chief, Environmental Chemistry Branch Environmental Sciences Division National Exposure Research Laboratory Office of Research and Development Environmental Protection Agency Las Vegas, Nevada 89119 [email protected] Office of Research and Development National Exposure Research Laboratory, Environmental Sciences Division, Las Vegas, Nevada Why and how do drugs contaminate the environment? What might it all mean? How do we prevent it? Office of Research and Development National Exposure Research Laboratory, Environmental Sciences Division, Las Vegas, Nevada This talk presents only a cursory overview of some of the many science issues surrounding the topic of pharmaceuticals as environmental contaminants Office of Research and Development National Exposure Research Laboratory, Environmental Sciences Division, Las Vegas, Nevada A Clarification We sometimes loosely (but incorrectly) refer to drugs, medicines, medications, or pharmaceuticals as being the substances that contaminant the environment. The actual environmental contaminants, however, are the active pharmaceutical ingredients – APIs. These terms are all often used interchangeably Office of Research and Development National Exposure Research Laboratory, Environmental Sciences Division, Las Vegas, Nevada Office of Research and Development Available: http://www.epa.gov/nerlesd1/chemistry/pharma/image/drawing.pdfNational -

Hikma Launches Vecuronium Bromide for Injection

Press Release Hikma launches Vecuronium Bromide for Injection London, April 3, 2020 – Hikma Pharmaceuticals PLC (Hikma, Group), the multinational generic pharmaceutical company, has launched Vecuronium Bromide for Injection, 10mg, in the United States through its US affiliate, Hikma Pharmaceuticals USA Inc.1 According to IQVIA, US sales of Vecuronium Bromide for Injection, 10mg, were approximately $6 million in the 12 months ending February 2020. Vecuronium Bromide for Injection is indicated as an adjunct to general anesthesia, to facilitate endotracheal intubation and to provide skeletal muscle relaxation during surgery or mechanical ventilation. Hikma is the third largest US supplier of generic injectable medicines by volume, with a growing portfolio of over 100 products. Today one in every six injectable generic medicines used in US hospitals is a Hikma product. - ENDS - Enquiries Hikma Pharmaceuticals PLC Susan Ringdal +44 (0)20 7399 2760/ +44 7776 477050 EVP, Strategic Planning and Global Affairs [email protected] Steve Weiss +1 732 720 2830/ +1 732 788 8279 David Belian +1 732 720 2814/+1 848 254 4875 US Communications and Public Affairs [email protected] About Hikma (LSE: HIK) (NASDAQ Dubai: HIK) (OTC: HKMPY) (rated Ba1/stable Moody's and BB+/positive S&P) Hikma helps put better health within reach every day for millions of people in more than 50 countries around the world. For more than 40 years, we've been creating high-quality medicines and making them accessible to the people who need them. Headquartered in the UK, we are a global company with a local presence across the United States (US), the Middle East and North Africa (MENA) and Europe, and we use our unique insight and expertise to transform cutting-edge science into innovative solutions that transform people's lives.