Hidden Treasure? in Search of Mali’S Gold-Mining Revenues a C I R E M a M a F X O / F F O L E T T E R B

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Arend J Hoogervorst1 B.Sc.(Hons), Mphil., Pr.Sci

Audits & Training Eagle Environmental Arend J Hoogervorst1 B.Sc.(Hons), MPhil., Pr.Sci. Nat., MIEnvSci., C.Env., MIWM Environmental Audits Undertaken, Lectures given, and Training Courses Presented2 A) AUDITS UNDERTAKEN (1991 – Present) (Summary statistics at end of section.) Key ECA - Environmental Compliance Audit EMA - Environmental Management Audit EDDA -Environmental Due Diligence Audit EA- External or Supplier Audit or Verification Audit HSEC – Health, Safety, Environment & Community Audit (SHE) – denotes safety and occupational health issues also dealt with * denotes AJH was lead environmental auditor # denotes AJH was contracted specialist local environmental auditor for overseas environmental consultancy, auditing firm or client + denotes work undertaken as an ICMI-accredited Lead Auditor (Cyanide Code) No of days shown indicates number of actual days on site for audit. [number] denotes number of days involved in audit preparation and report write up. 1991 *2 day [4] ECA - AECI Chlor-Alkali Plastics, Umbogintwini, KwaZulu-Natal, South Africa. November 1991. *2 day [4] ECA - AECI Chlor-Alkali Plastics- Environmental Services, Umbogintwini, KwaZulu-Natal, South Africa. November 1991. *2 Day [4] ECA - Soda Ash Botswana, Sua Pan, Botswana. November 1991. 1992 *2 Day [4] EA - Waste-tech Margolis, hazardous landfill site, Gauteng, South Africa. February 1992. *2 Day [4] EA - Thor Chemicals Mercury Reprocessing Plant, Cato Ridge, KwaZulu-Natal, South Africa. March 1992. 2 Day [4] EMA - AECI Explosives Plant, Modderfontein, Gauteng, South Africa. March 1992. *2 Day [4] EMA - Anikem Water Treatment Chemicals, Umbogintwini, KwaZulu-Natal, South Africa. March 1992. *2 Day [4] EMA - AECI Chlor-Alkali Plastics Operations Services Group, Midland Factory, Sasolburg. March 1992. *2 Day [4] EMA - SA Tioxide factory, Umbogintwini, KwaZulu-Natal, South Africa. -

Le Développement Économique Local TERRITOIRE, FILIÈRES ET ENTREPRENARIAT

Le Développement Économique Local TERRITOIRE, FILIÈRES ET ENTREPRENARIAT Expériences dans le bassin du fleuve Sénégal (Mauritanie, Mali, Sénégal) 1 Migration - Citoyenneté - Développement Ce guide a été élaboré dans le cadre du programme d’appui aux initiatives de développement local et de coopératives territoriales. Ce programme est mis en œuvre dans le bassin du fleuve Sénégal en partenariat avec des acteurs locaux partenaires associés du projet : • Pour le Mali, Le Conseil Régional de Kayes (CRK); • Pour le Sénégal, Les Agences Régionales de Développement (ARD) de Matam et de Tambacounda, les GIC de Bakel et du Bosséa ; • Pour la Mauritanie, L’Association des Maires du Guidimakha (AMaiG) et l’Association des Maires et Parlementaires du 2 Gorgol (AMPG) ; • Au niveau sous régional, l’association sénégalaise SAANE. Il a reçu le soutien financier de : l’Union Européenne, l’Agence française de développement, le CCFD- Terre Solidaire, le CFSI, les conseils régionaux (Centre, Ile de France, Nord-pas-de-Calais), la fondation Nicolas Hulot, la fondation Michelham. Rédaction : Karen Mbomozomo Comité de relecture : GRDR avec la participation de Jérôme Klefstad Sillonville Graphisme : Marie Guérin [email protected] Crédits photos : GRDR (sauf mention spéciale) © GRDR Février 2014 AVANT-PROPOS Le GRDR-Migration, Citoyenneté, cours de mise en œuvre, certaines des Développement a, dans sa stratégie de réflexions présentées ici ne sont pas recherche-action, le souci de capitaliser totalement abouties. Ce guide donne ses actions, de tirer des leçons de ses ainsi un aperçu des principaux outils expériences et de les valoriser en savoirs et méthodologies éprouvés tout au partageables. long de l’action (partie II). -

VEGETALE : Semences De Riz

MINISTERE DE L’AGRICULTURE REPUBLIQUE DU MALI ********* UN PEUPLE- UN BUT- UNE FOI DIRECTION NATIONALE DE L’AGRICULTURE APRAO/MALI DNA BULLETIN N°1 D’INFORMATION SUR LES SEMENCES D’ORIGINE VEGETALE : Semences de riz JANVIER 2012 1 LISTE DES ABREVIATIONS ACF : Action Contre la Faim APRAO : Amélioration de la Production de Riz en Afrique de l’Ouest CAPROSET : Centre Agro écologique de Production de Semences Tropicales CMDT : Compagnie Malienne de Développement de textile CRRA : Centre Régional de Recherche Agronomique DNA : Direction Nationale de l’Agriculture DRA : Direction Régionale de l’Agriculture ICRISAT: International Crops Research Institute for the Semi-Arid Tropics IER : Institut d’Economie Rurale IRD : International Recherche Développement MPDL : Mouvement pour le Développement Local ON : Office du Niger ONG : Organisation Non Gouvernementale OP : Organisation Paysanne PAFISEM : Projet d’Appui à la Filière Semencière du Mali PDRN : Projet de Diffusion du Riz Nérica RHK : Réseau des Horticulteurs de Kayes SSN : Service Semencier National WASA: West African Seeds Alliancy 2 INTRODUCTION Le Mali est un pays à vocation essentiellement agro pastorale. Depuis un certain temps, le Gouvernement a opté de faire du Mali une puissance agricole et faire de l’agriculture le moteur de la croissance économique. La réalisation de cette ambition passe par la combinaison de plusieurs facteurs dont la production et l’utilisation des semences certifiées. On note que la semence contribue à hauteur de 30-40% dans l’augmentation de la production agricole. En effet, les semences G4, R1 et R2 sont produites aussi bien par les structures techniques de l’Etat (Service Semencier National et l’IER) que par les sociétés et Coopératives semencières (FASO KABA, Cigogne, Comptoir 2000, etc.) ainsi que par les producteurs individuels à travers le pays. -

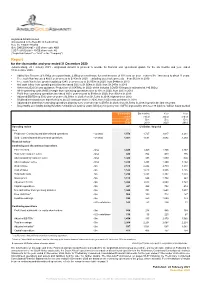

Year End 2020

AngloGold Ashanti Limited (Incorporated in the Republic of South Africa) Reg. No. 1944/017354/06 ISIN: ZAE000043485 – JSE share code: ANG CUSIP: 035128206 – NYSE share code: AU (“AngloGold Ashanti” or “AGA” or the “Company”) Report for the six months and year ended 31 December 2020 Johannesburg, 22 February 2021 - AngloGold Ashanti is pleased to provide its financial and operational update for the six months and year ended 31 December 2020. • Added Ore Reserve of 6.1Moz on a gross basis, 2.6Moz on a net basis, for a net increase of 10% year-on-year - reserve life ∧ increased to about 11 years • Free cash flow increased 485% year-on-year to $743m in 2020 – excluding asset sale proceeds – from $127m in 2019 • Free cash flow before growth capital up 124% year-on-year to $1,003m in 2020, from $448m in 2019 • Net cash inflow from operating activities increased 58% to $1,654m in 2020, from $1,047m in 2019 • Achieved 2020 full year guidance: Production of 3.047Moz in 2020, which includes COVID-19 impacts estimated at 140,000oz • All-in sustaining costs (AISC) margin from continuing operations rose to 40% in 2020, from 28% in 2019 • Profit from continuing operations increased 160% year-on-year to $946m in 2020, from $364m in 2019 • Adjusted EBITDA up 50% year-on-year to $2,593m in 2020, from $1,723m in 2019; highest since 2012 • Dividend increased more than fivefold to 48 US cents per share in 2020, from 9 US cents per share in 2019 • Adjusted net debt from continuing operations down by 62% year-on-year to $597m in 2020, from $1,581m in 2019; -

Annuaire Statistique 2015 Du Secteur Développement Rural

MINISTERE DE L’AGRICULTURE REPUBLIQUE DU MALI ----------------- Un Peuple - Un But – Une Foi SECRETARIAT GENERAL ----------------- ----------------- CELLULE DE PLANIFICATION ET DE STATISTIQUE / SECTEUR DEVELOPPEMENT RURAL Annuaire Statistique 2015 du Secteur Développement Rural Juin 2016 1 LISTE DES TABLEAUX Tableau 1 : Répartition de la population par région selon le genre en 2015 ............................................................ 10 Tableau 2 : Population agricole par région selon le genre en 2015 ........................................................................ 10 Tableau 3 : Répartition de la Population agricole selon la situation de résidence par région en 2015 .............. 10 Tableau 4 : Répartition de la population agricole par tranche d'âge et par sexe en 2015 ................................. 11 Tableau 5 : Répartition de la population agricole par tranche d'âge et par Région en 2015 ...................................... 11 Tableau 6 : Population agricole par tranche d'âge et selon la situation de résidence en 2015 ............. 12 Tableau 7 : Pluviométrie décadaire enregistrée par station et par mois en 2015 ..................................................... 15 Tableau 8 : Pluviométrie décadaire enregistrée par station et par mois en 2015 (suite) ................................... 16 Tableau 9 : Pluviométrie enregistrée par mois 2015 ........................................................................................ 17 Tableau 10 : Pluviométrie enregistrée par station en 2015 et sa comparaison à -

Anglogold Ashanti Holdings Plc Anglogold Ashanti Limited

Use these links to rapidly review the document TABLE OF CONTENTS Prospectus Supplement TABLE OF CONTENTS TABLE OF CONTENTS 3 Table of Contents Filed pursuant to Rule 424(b)(5) Registration Nos. 333-182712 and 333-182712-02 CALCULATION OF REGISTRATION FEE Amount of Registration Title of Each Class of Aggregate Securities to be Registered Offering Price Fee (1) 5.125% Notes due 2022 of AngloGold Ashanti Holdings plc $750,000,000 $85,950 Guarantee of AngloGold Ashanti Limited in connection with the 5.125% Notes due 2022 (2) — — (1) Calculated in accordance with Rule 457(r) under the Securities Act of 1933. (2) Pursuant to Rule 457(n) under the Securities Act of 1933, no separate fee is payable with respect to the guarantee of AngloGold Ashanti Limited in connection with the guaranteed debt securities. Prospectus Supplement to Prospectus dated July 17, 2012 GRAPHIC AngloGold Ashanti Holdings plc $750,000,000 5.125% notes due 2022 Fully and Unconditionally Guaranteed by AngloGold Ashanti Limited The 5.125% notes due 2022, or the "notes", will bear interest at a rate of 5.125% per year. AngloGold Ashanti Holdings plc, or "Holdings", will pay interest on the notes each February 1 and August 1, commencing on February 1, 2013. Unless Holdings redeems the notes earlier, the notes will mature on August 1, 2022. The notes will rank equally with Holdings' senior, unsecured debt obligations and the guarantee will rank equally with all other senior, unsecured debt obligations of AngloGold Ashanti Limited. Holdings may redeem some or all of the notes at any time and from time to time at the redemption price determined in the manner described in this prospectus supplement. -

SITUATION DES FOYERS DE FEUX DE BROUSSE DU 01 Au 03 NOVEMBRE 2014 SELON LE SATTELITE MODIS

MINISTERE DE L’ENVIRONNEMENT REPUBLIQUE DU MALI DE L’EAU ET DE l’ASSAINISSEMENT UN PEUPLE-UN BUT-UNE FOI DIRECTION NATIONALE DES EAUX ET FORETS(DNEF) SYSTEME D’INFORMATION FORESTIER (SIFOR) SITUATION DES FOYERS DE FEUX DE BROUSSE DU 01 au 03 NOVEMBRE 2014 SELON LE SATTELITE MODIS. LATITUDES LONGITUDES VILLAGES COMMUNES CERCLES REGIONS 11,0390000000 -7,9530000000 SANANA WASSOULOU-BALLE YANFOLILA SIKASSO 11,0710000000 -7,3840000000 KOTIE GARALO BOUGOUNI SIKASSO 11,1700000000 -6,9060000000 FOFO KOLONDIEBA KOLONDIEBA SIKASSO 11,2570000000 -6,8230000000 FAMORILA KOLONDIEBA KOLONDIEBA SIKASSO 11,4630000000 -6,4750000000 DOUGOUKOLO NIENA SIKASSO SIKASSO 11,4930000000 -6,6390000000 DIEDIOULA- KOUMANTOU BOUGOUNI SIKASSO 11,6050000000 -8,5470000000 SANANFARA NOUGA KANGABA KOULIKORO 11,6480000000 -8,5720000000 SAMAYA NOUGA KANGABA KOULIKORO 11,7490000000 -8,7950000000 KOFLATIE NOUGA KANGABA KOULIKORO 11,8600000000 -6,1890000000 BLENDIONI TELLA SIKASSO SIKASSO 11,9050000000 -8,3150000000 FIGUIRATOM MARAMANDOUGOU KANGABA KOULIKORO 11,9990000000 -10,676000000 DAR-SALM N SAGALO KENIEBA KAYES 12,0420000000 -8,7310000000 NOUGANI BENKADI KANGABA KOULIKORO 12,0500000000 -8,4440000000 OUORONINA BENKADI KANGABA KOULIKORO 12,1210000000 -8,3990000000 OUORONINA BANCOUMANA KATI KOULIKORO 12,1410000000 -8,7660000000 BALACOUMAN BALAN BAKAMA KANGABA KOULIKORO 12,1430000000 -8,7410000000 BALACOUMAN NARENA KANGABA KOULIKORO 12,1550000000 -8,4200000000 TIKO BANCOUMANA KATI KOULIKORO 12,1700000000 -9,8260000000 KIRIGINIA KOULOU KITA KAYES 12,1710000000 -10,760000000 -

Geometry and Genesis of the Giant Obuasi Gold Deposit, Ghana

Geometry and genesis of the giant Obuasi gold deposit, Ghana Denis Fougerouse, BSc, MSc This thesis is presented for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy. Centre for Exploration Targeting School of Earth and Environment The University of Western Australia July 2015 Supervisors: Dr Steven Micklethwaite Dr Stanislav Ulrich Dr John M Miller Professor T Campbell McCuaig ii "It never gets easier, you just go faster" Gregory James LeMond iv Abstract Abstract The supergiant Obuasi gold deposit is the largest deposit hosted in the Paleoproterozoic Birimian terranes of West Africa (62 Moz, cumulative past production and resources). The deposit is hosted in Kumasi Group sedimentary rocks composed of carbonaceous phyllites, slates, psammites, and volcaniclastic rocks intruded by different generations of felsic dykes and granites. In this study, the deformation history of the Obuasi district was re-evaluated and a three stage sequence defined based on observations from the regional to microscopic scale. The D1Ob stage is weakly recorded in the sedimentary rocks as a layer-parallel fabric. The D2Ob event is the main deformation stage and corresponds to a NW-SE shortening, involving tight to isoclinal folding, a pervasive subvertical S2Ob cleavage striking NE, as well as intense sub-horizontal stretching. Finally, a N-S shortening event (D3Ob) formed an ENE-striking, variably dipping S3Ob crenulation cleavage. Three ore bodies characteristic of the three main parallel mineralised trends were studied in details: the Anyankyerem in the Binsere trend; the Sibi deposit in the Gyabunsu trend, and the Obuasi deposit in the main trend. In the Obuasi deposit, two distinct styles of gold mineralisation occur; (1) gold-bearing sulphides, dominantly arsenopyrite, disseminated in metasedimentary rocks and (2) native gold hosted in quartz veins up to 25 m wide. -

Mli0006 Ref Region De Kayes A3 15092013

MALI - Région de Kayes: Carte de référence (Septembre 2013) Limite d'Etat Limite de Région MAURITANIE Gogui Sahel Limite de Cercle Diarrah Kremis Nioro Diaye Tougoune Yerere Kirane Coura Ranga Baniere Gory Kaniaga Limite de Commune Troungoumbe Koro GUIDIME Gavinane ! Karakoro Koussane NIORO Toya Guadiaba Diafounou Guedebine Diabigue .! Chef-lieu de Région Kadiel Diongaga ! Guetema Fanga Youri Marekhaffo YELIMANE Korera Kore ! Chef-lieu de Cercle Djelebou Konsiga Bema Diafounou Fassoudebe Soumpou Gory Simby CERCLES Sero Groumera Diamanou Sandare BAFOULABE Guidimakan Tafasirga Bangassi Marintoumania Tringa Dioumara Gory Koussata DIEMA Sony Gopela Lakamane Fegui Diangounte Goumera KAYES Somankidi Marena Camara DIEMA Kouniakary Diombougou ! Khouloum KENIEBA Kemene Dianguirde KOULIKORO Faleme KAYES Diakon Gomitradougou Tambo Same .!! Sansankide Colombine Dieoura Madiga Diomgoma Lambidou KITA Hawa Segala Sacko Dembaya Fatao NIORO Logo Sidibela Tomora Sefeto YELIMANE Diallan Nord Guemoukouraba Djougoun Cette carte a été réalisée selon le découpage Diamou Sadiola Kontela administratif du Mali à partir des données de la Dindenko Sefeto Direction Nationale des Collectivités Territoriales Ouest (DNCT) BAFOULABE Kourounnikoto CERCLE COMMUNE NOM CERCLE COMMUNE NOM ! BAFOULABE KITA BAFOULABE Bafoulabé BADIA Dafela Nom de la carte: Madina BAMAFELE Diokeli BENDOUGOUBA Bendougouba DIAKON Diakon BENKADI FOUNIA Founia Moriba MLI0006 REF REGION DE KAYES A3 15092013 DIALLAN Dialan BOUDOFO Boudofo Namala DIOKELI Diokeli BOUGARIBAYA Bougarybaya Date de création: -

Modelling the Optimum Interface Between Open Pit and Underground Mining for Gold Mines

MODELLING THE OPTIMUM INTERFACE BETWEEN OPEN PIT AND UNDERGROUND MINING FOR GOLD MINES Seth Opoku A thesis submitted to the Faculty of Engineering and the Built Environment, University of the Witwatersrand, Johannesburg, in fulfilment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy. Johannesburg 2013 DECLARATION I declare that this thesis is my own unaided work. Where use was made of the work of others, it was duly acknowledged. It is being submitted for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy in the University of the Witwatersrand, Johannesburg. It has not been submitted before in any form for any degree or examination at any other university. Signed …………………………….. (Seth Opoku) This……………….day of……………..………2013 i ABSTRACT The open pit to underground transition problem involves the decision of when, how and at what depth to transition from open pit (OP) to underground (UG). However, the current criteria guiding the process of the OP – UG transition are not well defined and documented as most mines rely on their project feasibility teams’ experiences. In addition, the methodologies used to address this problem have been based on deterministic approaches. The deterministic approaches cannot address the practicalities that mining companies face during decision-making, such as uncertainties in the geological models and optimisation parameters, thus rendering deterministic solutions inadequate. In order to address these shortcomings, this research reviewed the OP – UG transition problem from a stochastic or probabilistic perspective. To address the uncertainties in the geological models, simulated models were generated and used. In this study, transition indicators used for the OP - UG transition were Net Present Value (NPV), ratio of price to cost per ounce of gold, stripping ratio, processed ounces and average grade at the run of mine pad. -

Phase II 2007 / 2009 – Région De Kayes - Mali

GRDR Groupe de recherche et de réalisations pour le développement rural Migration, citoyenneté et développement 66/72 rue Marceau 93109 Montreuil France Métro : Robespierre Tél. 01 48 57 75 80 Fax. 01 48 57 59 75 Email : [email protected] www.grdr.org 1901 oi l Association Appui aux Initiatives de Développement Local en Région de Kayes – Phase II 2007 / 2009 – Région de Kayes - Mali Janvier 2007 GRDR Mali BP. 291, Rue 136, porte n°37 – Légal Ségou face SEMOS – Kayes, Mali Tél. : (+) 223 252 29 82 et Fax : (+) 223 253 14 60 Courriel : [email protected] 1 SOMMAIRE I Synthèse du projet ____________________________________________________________ 5 1. Titre du projet __________________________________________________________________ 5 2. Localisation exacte_______________________________________________________________ 5 3. Calendrier prévisionnel___________________________________________________________ 5 4. Objet du projet _________________________________________________________________ 5 5. Moyens à mettre en œuvre ________________________________________________________ 7 6. Conditions de pérennisation de l’action après sa clôture________________________________ 7 7. Cohérence de l’action par rapport aux politiques nationales ____________________________ 7 8. Cohérence de l’action par rapport aux actions bilatérales françaises dans le pays __________ 8 II Présentation des partenaires locaux______________________________________________ 9 1. Assemblée Régionale de Kayes_____________________________________________________ 9 2. Association des -

Cercle De Kayes

Cercle de Kayes REPERTOIRE Des fonds clos du Cercle de Kayes (Document provisoire) 275 CARTONS- 30,25 METRES LINEAIRES Août 2010 LES ARCHIVES Les archives jouent un rôle important dans la vie administrative, économique, sociale et culturelle d’un pays. Le développement économique, social et culturel d’un pays dépend de la bonne organisation de ses archives. Les documents d’archives possèdent une valeur probatoire, sans eux, rien ne pourrait être affirmé avec certitude, car le témoignage humain est sujet à l’erreur et à l’oubli. Les documents d’archives doivent fonctionner comme le rouage essentiel de l’Administration, et fournissent des ressources indispensables à la recherche. Les archives représentent la mémoire d’un pays. La bonne organisation des archives est un des aspects de la bonne organisation administrative. Il faut que chacun ait conscience que chaque fois qu’on détruit ou laisse détruire des archives, c’est une possibilité de gouverner qui disparaît, c’est-à-dire une part du passé de notre nation. La vigilance est un devoir. 2 Série A – Actes officiels Carton A/1–A/2-A/3 : A/1 : - Projet de constitution (1958) - Loi (1959) - Loi n˚52-130 du 6 février 1952 relative à la formation des Assemblées locales - document endommagé (1952) - Loi électorale adoptée en première lecture le 24 avril 1951 par l’Assemblée nationale (1951) - Projet de loi relatif à la formation des Assemblées du Groupe et des Assemblées locales de l’AOF, l’AEF, Cameroun, Togo et Madagascar (1951) A/2 : - Ordonnance désignant un agent d’exécution. Ordonnance