Evaluation of the Predictive Validity of the Behavioural Assessment for Re-Homing K9’S (B.A.R.K.) Protocol and Owner Satisfaction with Adopted Dogs

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

MAC1 Abstracts – Oral Presentations

Oral Presentation Abstracts OP001 Rights, Interests and Moral Standing: a critical examination of dialogue between Regan and Frey. Rebekah Humphreys Cardiff University, Cardiff, United Kingdom This paper aims to assess R. G. Frey’s analysis of Leonard Nelson’s argument (that links interests to rights). Frey argues that claims that animals have rights or interests have not been established. Frey’s contentions that animals have not been shown to have rights nor interests will be discussed in turn, but the main focus will be on Frey’s claim that animals have not been shown to have interests. One way Frey analyses this latter claim is by considering H. J. McCloskey’s denial of the claim and Tom Regan’s criticism of this denial. While Frey’s position on animal interests does not depend on McCloskey’s views, he believes that a consideration of McCloskey’s views will reveal that Nelson’s argument (linking interests to rights) has not been established as sound. My discussion (of Frey’s scrutiny of Nelson’s argument) will centre only on the dialogue between Regan and Frey in respect of McCloskey’s argument. OP002 Can Special Relations Ground the Privileged Moral Status of Humans Over Animals? Robert Jones California State University, Chico, United States Much contemporary philosophical work regarding the moral considerability of nonhuman animals involves the search for some set of characteristics or properties that nonhuman animals possess sufficient for their robust membership in the sphere of things morally considerable. The most common strategy has been to identify some set of properties intrinsic to the animals themselves. -

Understanding Human Factors Involved in the Unwanted Cat Problem

UNDERSTANDING HUMAN FACTORS INVOLVED IN THE UNWANTED CAT PROBLEM Sarah Jane Maria Zito BVetMed MANZCVS (feline medicine) A thesis submitted for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy at The University of Queensland in 2015 School of Veterinary Science I Abstract The large number of unwanted cats in many modern communities results in a complex, worldwide problem causing many societal issues. These include ethical concerns about the euthanasia of many healthy animals, moral stress for the people involved, financial costs to organisations that manage unwanted cats, environmental costs, wildlife predation, potential for disease spread, community nuisance, and welfare concerns for cats. Humans contribute to the creation and maintenance of unwanted cat populations and also to solutions to alleviate the problem. The work in this thesis explored human factors contributing to the unwanted cat problem—including cat ownership perception, cat caretaking, cat semi-ownership and cat surrender—and human factors associated with cat adoption choices and outcomes. To investigate human factors contributing to the unwanted cat problem, data were collected from 141 people surrendering cats to four animal shelters. The aim was to better understand the people and human-cat relationships involved, and ultimately to inform strategies to reduce shelter intake. Participants were recruited for this study when they surrendered a cat to a shelter and information was obtained on their demographics, cat interaction history, cat caretaking, and surrender reasons. This information was used to describe and compare the people, cats, and human-cat relationships contributing to shelter intake, using logistic regression models and biplot visualisation techniques. A model of cat ownership perception in people that surrender cats to shelters was proposed. -

Exploring Human – Animal Interactions a Multidisciplinary Approach from Behavioral and Social Sciences

Proceedings Exploring Human – Animal Interactions a multidisciplinary approach from behavioral and social sciences Barcelona 7th – 10th of July 2016 INTRODUCTION Vision, Goals and Objectives Animals were domesticated thousands of years ago and are now present in almost every human society around the world. Nevertheless, only recently scientists have begun to analyse both positive and negative aspects of human-animal relationships. For centuries people have recognised the value of animals for obvious economical reasons, but also as an important source of physical and emotional wellbeing. Indeed, people’s attitudes towards animals depend on a variety of factors, including socio-economical relationships with each particular species, cultural background, religious believes, as well as individual differences regarding behaviour and personality. A proper understanding of these differences requires a multidisciplinary approach, from psychology, social psychology and anthropology to psychiatry and neuroscience. The main goal of the conference would be to provide delegates with an updated and multi-disciplinary overview of human-animal interactions. Selected topics would include but are not limited to: • The concept of empathy in the study of human-animals interactions. • The concept of protected values (or sacred values) in human-animal interactions. • Understanding cultural views on animals. We will also organise a Satellite Meeting (10th of July) on the state of the art of the abandonment of companion animals and global strategies to prevent the abandonment. ISAZ grateFULLY acKnoWLedges the generous support OF the 2016 conFerence FroM the FOLLOWing sponsors and COLLaborators Sponsors Collaborators 2 PROGRAM Thursday 7th July Friday 8th July 19:00 – 20:30 8:00 – 18:30 Welcome Ceremony Registration at the PRBB Barcelona City Council 9:00 – 9:15 Opening address 9:15 – 10:15 Keynote Speaker Dr. -

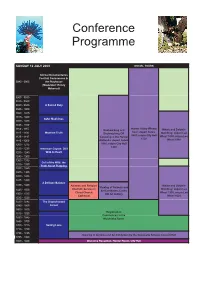

Conference Programme

Conference Programme SUNDAY 12 JULY 2009 SOCIAL TOURS Animal Documentaries Festival Commences in 0845 - 0900 the Playhouse (Moderator: Randy Malamud) 0900 - 0915 0915 - 0930 0930 - 0945 A Sacred Duty 0945 - 1000 1000 - 1015 1015 - 1030 Safer Medicines 1030 - 1045 1045 - 1100 1100-1115 Hunter Valley Winery Bushwalking and Whale and Dolphin Tour: depart hotels 1115 - 1130 Meat the Truth Birdwatching OR Watching: depart Lee 0845, return City Hall 1130 - 1145 Canoeing in the Hunter Wharf 1000, return Lee 1530 1145 - 1200 Wetlands: depart hotels Wharf 1300 1200 - 1215 0900, return City Hall 1430 1215 - 1230 American Coyote: Still 1230 - 1245 Wild At Heart 1245 - 1300 1300 - 1315 Cull of the Wild: the 1315 - 1330 Truth About Trapping 1330 - 1345 1345 - 1400 1400 - 1415 1415 - 1430 A Delicate Balance 1430 - 1445 Animals and Religion Whale and Dolphin Viewing of Animals and Interfaith Service in Watching: depart Lee 1445 - 1500 Art Exhibition, Cooks Christ Church Wharf 1330, return Lee 1500 - 1515 Hill Art Gallery Cathedral Wharf 1630 1515 - 1530 1530 - 1545 The Disenchanted 1545 - 1600 Forest 1600 - 1615 Registration 1615 - 1630 Commences in the 1630 - 1645 Mulubinba Room 1645 - 1700 1700 - 1715 Saving Luna 1715 - 1730 1730 - 1745 Viewing of Animals and Art Exhibition by the Newcastle School, Concert Hall 1745 - 1800 1800 - 1930 Welcome Reception, Hunter Room, City Hall MONDAY 13 JULY 2009 Banquet Room 0800 - 0900 Registration Concert Hall 0900 - 0905 Introductions: Rod Bennison and Jill Bough, Minding Animals Conference Co-convenors, Animals -

People & Animals – for Life

PEOPLE & ANIMALS – FOR LIFE The Conference is hosted on behalf of the International Association of Human-Animal Interaction Organizations by the Swedish IAHAIO members 12th International IAHAIO Conference JULY 1-4, 2010 STOCKHOLM, SWEDEN Venue: City Conference Center - Folkets Hus in Stockholm Website: www.iahaio2010.com Abstract Book Major Sponsors 2 Table of Contents Plenary Sessions 4 Plenary 1-9 5 Oral Sessions (Thursday July 1) 14 Oral 1-12 15 Oral Sessions (Friday July 2) 27 Oral 13-42 28 Oral Sessions (Saturday July 3) 57 Oral 43-66 58 Oral Sessions (Sunday July 4) 82 Oral 67-87 83 Workshops 104 Workshops 1-17 105 Poster Sessions 122 Poster 1-40 123 All abstracts are published exactly as their respective authors wrote them. © IAHAIO and respective authors. 3 Plenary Sessions Abstract from Plenary speakers 4 Plenary session 1 Some We Love, Some We Hate, Some We Eat: Why It’s So Hard to Think Straight about Animals Harold Herzog Professor, Western Carolina University Our attitudes toward non-human animals are often morally incoherent. How can most Americans claim WKH\VXSSRUWWKHDLPVRIWKHDQLPDOULJKWVPRYHPHQW\HWRIDGXOWVLQWKH8QLWHV6WDWHVHDWÁHVK":K\ GRZHORYHFDWVDQGKDWHUDWV":K\DUHGRJVWUHDWHGDVIDPLO\PHPEHUVLQVRPHFRXQWULHVDQGHDWHQIRU GLQQHULQRWKHUV",QWKLVSUHVHQWDWLRQ,ZLOOXVHUHFHQWÀQGLQJVIURPDQWKURSRORJ\SV\FKRORJ\DQGEUDLQ science to examine why human interactions with other species are so fraught with inconsistency. 2XUWKLQNLQJDERXWQRQKXPDQDQLPDOVUHÁHFWVDFRPSOH[PL[RIJHQHWLFFXOWXUDODQGFRJQLWLYHIDFWRUV These include biophilia and biophobia, learning, language, and the tendency for human decision-making to rely on quick and dirty rules of thumb. I will argue that the social intuitionist model of moral judgment (Haidt, 2001) helps explain why our relationships with other species are so ethically messy. This theory holds WKDWPRUDOGHFLVLRQVLQYROYHWZRGLVWLQFWDQGRIWHQFRQÁLFWLQJSURFHVVHV7KHÀUVWLVUDSLGXQFRQVFLRXVDQG intuitive, while the second is slow, conscious and logical. -

Proceedings Science Week 2013

Proceedings Veterinary Behaviour Chapter Science Week 2013 QT Gold Coast 11 – 13 July 2013 SCIENCE WEEK 2013 Veterinary Behaviour Chapter Science Week programme co-ordinators: Dr Cam Day and Dr Kersti Seksel Proceedings Editors: Dr Gaille Perry and Dr Kersti Seksel Abstract Reviewers: Dr Jacqui Ley Dr Caroline Perrin Dr Gaille Perry Collation of Proceedings: Dr Norm Blackman Dr Cam Day Dr Gaille Perry Dr Kersti Seksel Veterinary Behaviour Chapter Proceedings – Science Week 2013 Contents Science Week Speaker Details ....................................................................................................... 1 BOVA .................................................................................................................................................. 1 Dr Gabrielle Carter ........................................................................................................................... 1 Dr Heather Chee ............................................................................................................................... 1 Dr Amanda Cole ............................................................................................................................... 1 Dr Kevin Cruickshank....................................................................................................................... 2 Dr Cam Day ....................................................................................................................................... 2 Dr Sally Gardiner ............................................................................................................................. -

Research Group, Monash University Editorial Committee: Timothy Adams Bvsc (Hons), Petcare Information and Advisory Service

Shelresearcterh 12th Edition: 2010 Editor: Kate Mornement BSc (Hons), PhD student, Building on your Anthrozoology Research Group, Monash University Editorial Committee: Timothy Adams BVSc (Hons), Petcare Information and Advisory Service strengths within the PhD Dr. Pauleen Bennett , Founder, Anthrozoology Research Group, Monash University Dr. Linda Marston PhD, Research Fellow, shelter environment Anthrozoology Research Group, Monash University by Vanessa Rohlf What is positive psychology? Positive psychology is a new and rapidly growing field of Psychology. Unlike traditional models of Psychology, Positive Psychology is concerned with the study of optimal human functioning rather than pathology. Basically positive psychologists are concerned with understanding and promoting happiness. Understanding and Promoting Happiness According to the founder of Positive Psychology, Martin Seligman, there are three ways to be happy; Pleasure, Engagement and Meaning (Seligman, 2002). Pleasure – is all about increasing positive emotions. Positive emotions can be increased by focusing on Promoting happiness in the workplace the past, present or future. We can People spend on average a third of their lives at work so it is experience positive emotions about extremely important to cultivate happiness in the workplace. the past by practicing gratitude. Working in an animal shelter is no different – especially when Positive emotions about the present you often have to deal with unhappy situations. Research also can be experienced by savouring (e.g. indicates that there may be a flow on effect. Satisfaction with savouring the taste of a chocolate bar). work is associated with life satisfaction as well as reduced Positive emotions about the future can levels of conflict in the home (Diener & Seligman, 2004). -

Co-Sleeping Between Adolescents and Their Pets May Not Impact Sleep Quality

Article Co-Sleeping between Adolescents and Their Pets May Not Impact Sleep Quality Jessica Rosano 1, Tiffani Howell 1,*, Russell Conduit 2 and Pauleen Bennett 1 1 Anthrozoology Research Group, School of Psychology and Public Health, La Trobe University, Bendigo, VIC 3552, Australia; [email protected] (J.R.); [email protected] (P.B.) 2 School of Health and Biomedical Sciences, RMIT University, Melbourne, VIC 3083, Australia; [email protected] * Correspondence: [email protected] Abstract: Pet–owner co-sleeping is increasingly common in some parts of the world. Adult owners often subjectively report benefits of co-sleeping with pets, although objective actigraphy reports conversely indicate sleep disruptions due to the pet. Because limited research is available regarding pet–owner co-sleeping in non-adult samples, the aim of this two-part study was to explore whether co-sleeping improves sleep quality in adolescents, an age group in which poor sleep patterns are well documented. In Study One, an online survey with 265 pet-owning 13-to-17-year-old participants found that over 78% co-slept with their pet. Average sleep quality scores for co-sleepers and non- co-sleepers indicated generally poor sleep, with no differences in sleep quality depending on age, gender, or co-sleeping status. Study Two consisted of two preliminary case studies, using actigraphy on dog–adolescent co-sleepers. In both cases, high sleep concordance was observed, but owners again experienced generally poor sleep quality. Future actigraphy research is needed, including larger sample sizes and a control group of non-co-sleepers, to validate the preliminary findings from this study, but our limited evidence suggests that co-sleeping with a pet may not impact sleep quality in adolescents. -

2012 Conference Abstract Booklet:Layout 1

ISAZ2012 The Arts & Sciences of Human–Animal Interaction 11 to 13 July, 2012 Murray Edwards College, Cambridge, UK Abstracts appear as they were submitted. Their content have not been changed, although their appearance may have been changed for stylistic reasons. © International Society for Anthrozoology HAI Research Funding Forum: Tips for Success • Do you want to learn about the Human-Animal Interaction research that’s currently being co-funded by the U.S. National Institutes of Health (NIH) and Mars-WALTHAM®? • Do you want to learn how to navigate the NIH and WALTHAM® grant application processes? If so, then please plan to attend this session being hosted by the Eunice Kennedy Shriver National Institute of Child Health & Human Development (NICHD), WALTHAM®, and Mars, Incorporated. Wednesday, 11 July 2012 12:30pm – 2:00pm Buckingham House Seminar Room: Research Poster Viewing 1:00pm – 1:50pm Buckingham House Lecture Theatre: Funding Presentation During the lunch break, representatives from the public-private partnership formed between NICHD/Mars-WALTHAM® will provide real-world advice— taken from the NIH peer-review of HAI research applications—about how to navigate the NIH and WALTHAM® grant application processes and improve your chances of submitting a successful proposal. In addition, research posters will be available for viewing in the Buckingham House Seminar Room, featuring studies currently receiving funding through the partnership. About the International Society for Anthrozoology The International Society for Anthrozoology (ISAZ) was formed in 1991 as a supportive organization for the scientific and scholarly study of human–animal interactions. ISAZ is a nonprofit, nonpolitical organization with a worldwide, multi-disciplinary membership of students, scholars and interested professionals. -

Journal of Animal & Natural Resource

JOURNAL OF ANIMAL & NATURAL RESOURCE LAW Michigan State University College of Law MAY 2016 VOLUME XII The Journal of Animal & Natural Resource Law is published annually by law students at Michigan State University College of Law. JOURNAL OF ANIMAL & The Journal of Animal & Natural Resource Law received generous support from the NATURAL RESOURCE LAW Animal Legal Defense Fund and the Michigan State University College of Law. Without their generous support, the Journal would not have been able to publish and VOL. XII 2016 host its annual symposium. The Journal also is funded by subscription revenues. Subscription requests and article submissions may be sent to: Professor David Favre, Journal of Animal & Natural Resource Law, Michigan State University College of Law, EDITORIAL BOARD 368 Law College Building, East Lansing MI 48824, or by email to [email protected]. 2015-2016 Current yearly subscription rates are $27.00 in the U.S. and current yearly Internet subscription rates are $27.00. Subscriptions are renewed automatically unless a Editor-in-Chief request for discontinuance is received. CLAIRE CORSEY Back issues may be obtained from: William S. Hein & Co., Inc., 1285 Main Street, Buffalo, NY 14209. Executive Editor Managing Editor Articles Editors EMILY JEFFERSON PETER BELTZ SAMANTHA REASNER The Journal of Animal & Natural Resource Law welcomes the submission of articles, book reviews, and notes & comments. Each manuscript must be double spaced, in DEEMA TARAZI 12 point, Times New Roman; footnotes must be single spaced, 10 point, Times New Roman. Submissions should be sent to [email protected] using Microsoft Word or PDF format. Submissions should conform closely to the 19th edition of The Bluebook: Business Editor Notes Editor A Uniform System of Citation. -

Subjective Influence of Human-Animal Relationships on Risk Perception, and Risk Behaviour During Bushfire Threat

The Qualitative Report Volume 21 Number 10 Article 9 10-17-2016 A Moveable Beast: Subjective Influence of Human-Animal Relationships on Risk Perception, and Risk Behaviour during Bushfire Threat Joshua L. Trigg Central Queensland University, [email protected] Kirrilly Thompson Central Queensland University, [email protected] Bradley Smith Central Queensland University, [email protected] Pauleen Bennett La Trobe University, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://nsuworks.nova.edu/tqr Part of the Animal Studies Commons, Community Psychology Commons, Emergency and Disaster Management Commons, Quantitative, Qualitative, Comparative, and Historical Methodologies Commons, and the Social Psychology Commons Recommended APA Citation Trigg, J. L., Thompson, K., Smith, B., & Bennett, P. (2016). A Moveable Beast: Subjective Influence of Human-Animal Relationships on Risk Perception, and Risk Behaviour during Bushfire Threat. The Qualitative Report, 21(10), 1881-1903. https://doi.org/10.46743/2160-3715/2016.2494 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the The Qualitative Report at NSUWorks. It has been accepted for inclusion in The Qualitative Report by an authorized administrator of NSUWorks. For more information, please contact [email protected]. A Moveable Beast: Subjective Influence of Human-Animal Relationships on Risk Perception, and Risk Behaviour during Bushfire Threat Abstract This article examines how human-animal connections influence risk perception and behaviour in companion animal guardians exposed to bushfire threat in Australia. Although the objective role of psychological bonds with companion animals is well accepted by researchers, subjective interpretations of these bonds by animal guardians are relatively underexamined in this context. -

5 July 2018, Sydney, Australia Page | 1

27th International Society for Anthrozoology Conference | 2 – 5 July 2018, Sydney, Australia Page | 1 27th International Society for Anthrozoology Conference | 2 – 5 July 2018, Sydney, Australia Page | 2 CONTENTS UNIVERSITY OF SYDNEY MAP INSIDE FRONT COVER WELCOME TO ISAZ 2018 4 ISAZ 2018 VOLUNTEERS 4 ABOUT THE INTERNATIONAL SOCIETY FOR ANTHROZOOLOGY 5 SPONSORS AND SUPPORTERS 6 DELEGATE INFORMATION 8 SOCIAL MEDIA – #ISAZ2018 12 PLENARY SPEAKERS 13 PROGRAM OVERVIEW 16 PROGRAM 25 MONDAY 2 JULY 2018 25 TUESDAY 3 JULY 2018 26 WEDNESDAY 4 JULY 2018 32 THURSDAY 5 JULY 2018 37 POSTER LISTING 41 ORAL ABSTRACTS 45 ISAZ SYMPOSIA SUMMARIES 92 POSTER ABSTRACTS 101 ABSTRACT REVIEWERS 128 AUTHOR INDEX 129 ATTENDEES 132 NOTES 137 27th International Society for Anthrozoology Conference | 2 – 5 July 2018, Sydney, Australia Page | 3 WELCOME TO ISAZ 2018 G'day, We are thrilled to welcome you to Sydney, Australia and the 27th annual conference of the International Society for Anthrozoology (ISAZ). ISAZ has never held a conference in the southern hemisphere before, so we are even more excited to welcome you here. Australia represents a perfect location because we have a large and ever-growing anthrozoology community, and we are home to some of the world’s unique wildlife! With this in mind, we have named several of our rooms after our favourite Aussie animals - including the kangaroo, dingo, platypus, galah, and the kookaburra. We had an overwhelming response to our call for abstracts and symposia. This has resulted in ISAZ's biggest program ever, with four concurrent sessions per day - six plenary talks, almost 100 oral presentations, 11 symposia and over 50 posters.