Oral Health and Disease

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Lumps and Swellings

Clinical Oral medicine for the general practitioner: lumps and swellings Crispian Scully 1 his series of five papers summarises some of the most important oral medicine problems likely to be Tencountered by practitioners. Some are common, others rare. The practitioner cannot be expected to diagnose all, but has been trained to recognise oral health and disease, and should be competent to recognise normal variants, and common orofacial disorders. In any case of doubt, the practitioner is advised to seek a second opinion from a colleague. The series is not intended to be comprehensive in coverage either of the conditions encountered, or all aspects of Figure 1: Torus mandibularis. diagnosis or treatment: further details are available in standard texts, in the further reading section, or from the internet. The present article discusses aspects of lumps through fear, perhaps after hearing of someone with and swellings. ‘mouth cancer’. Thus some individuals discover and worry about normal anatomical features such as tori, the parotid Lumps and swellings papilla, foliate papillae on the tongue, or the pterygoid Lumps and swellings in the mouth are common, but of hamulus. The tongue often detects even a very small diverse aetiologies (Table 1), and some represent swelling, or the patient may first notice it because it is sore malignant neoplasms. Therefore, this article will discuss (Figure 1). In contrast, many oral cancers are diagnosed far lumps and swellings in general terms, but later focus on too late, often after being present several months, usually the particular problems of oral cancer and of orofacial because the patient ignores the swelling. -

Glossary for Narrative Writing

Periodontal Assessment and Treatment Planning Gingival description Color: o pink o erythematous o cyanotic o racial pigmentation o metallic pigmentation o uniformity Contour: o recession o clefts o enlarged papillae o cratered papillae o blunted papillae o highly rolled o bulbous o knife-edged o scalloped o stippled Consistency: o firm o edematous o hyperplastic o fibrotic Band of gingiva: o amount o quality o location o treatability Bleeding tendency: o sulcus base, lining o gingival margins Suppuration Sinus tract formation Pocket depths Pseudopockets Frena Pain Other pathology Dental Description Defective restorations: o overhangs o open contacts o poor contours Fractured cusps 1 ww.links2success.biz [email protected] 914-303-6464 Caries Deposits: o Type . plaque . calculus . stain . matera alba o Location . supragingival . subgingival o Severity . mild . moderate . severe Wear facets Percussion sensitivity Tooth vitality Attrition, erosion, abrasion Occlusal plane level Occlusion findings Furcations Mobility Fremitus Radiographic findings Film dates Crown:root ratio Amount of bone loss o horizontal; vertical o localized; generalized Root length and shape Overhangs Bulbous crowns Fenestrations Dehiscences Tooth resorption Retained root tips Impacted teeth Root proximities Tilted teeth Radiolucencies/opacities Etiologic factors Local: o plaque o calculus o overhangs 2 ww.links2success.biz [email protected] 914-303-6464 o orthodontic apparatus o open margins o open contacts o improper -

Oral Diagnosis: the Clinician's Guide

Wright An imprint of Elsevier Science Limited Robert Stevenson House, 1-3 Baxter's Place, Leith Walk, Edinburgh EH I 3AF First published :WOO Reprinted 2002. 238 7X69. fax: (+ 1) 215 238 2239, e-mail: [email protected]. You may also complete your request on-line via the Elsevier Science homepage (http://www.elsevier.com). by selecting'Customer Support' and then 'Obtaining Permissions·. British Library Cataloguing in Publication Data A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library Library of Congress Cataloging in Publication Data A catalog record for this book is available from the Library of Congress ISBN 0 7236 1040 I _ your source for books. journals and multimedia in the health sciences www.elsevierhealth.com Composition by Scribe Design, Gillingham, Kent Printed and bound in China Contents Preface vii Acknowledgements ix 1 The challenge of diagnosis 1 2 The history 4 3 Examination 11 4 Diagnostic tests 33 5 Pain of dental origin 71 6 Pain of non-dental origin 99 7 Trauma 124 8 Infection 140 9 Cysts 160 10 Ulcers 185 11 White patches 210 12 Bumps, lumps and swellings 226 13 Oral changes in systemic disease 263 14 Oral consequences of medication 290 Index 299 Preface The foundation of any form of successful treatment is accurate diagnosis. Though scientifically based, dentistry is also an art. This is evident in the provision of operative dental care and also in the diagnosis of oral and dental diseases. While diagnostic skills will be developed and enhanced by experience, it is essential that every prospective dentist is taught how to develop a structured and comprehensive approach to oral diagnosis. -

WHAT HAPPENED? CDR, a 24-Year-Old Chinese Male

CHILDHOOD DEVELOPMENTAL SCREENING 2020 https://doi.org/10.33591/sfp.46.5.up1 FINDING A MASS WITHIN THE ORAL CAVITY: WHAT ARE THE COMMON CAUSES AND 4-7 GAINING INSIGHT: WHAT ARE THE ISSUES? In Figure 2 below, a list of masses that could arise from each site Figure 3. Most common oral masses What are the common salivary gland pathologies Salivary gland tumours (Figure 7) commonly present as channel referrals to appropriate specialists who are better HOW SHOULD A GP MANAGE THEM? of the oral cavity is given and elaborated briey. Among the that a GP should be aware of? painless growing masses which are usually benign. ey can equipped in centres to accurately diagnose and treat these Mr Tan Tai Joum, Dr Marie Stella P Cruz CDR had a slow-growing mass in the oral cavity over one year more common oral masses are: torus palatinus, torus occur in both major and minor salivary glands but are most patients, which usually involves surgical excision. but sought treatment only when he experienced a sudden acute mandibularis, pyogenic granuloma, mucocele, broma, ere are three pairs of major salivary glands (parotid, commonly found occurring in the parotid glands. e most 3) Salivary gland pathology may be primary or secondary to submandibular and sublingual) as well as hundreds of minor ABSTRACT onset of severe pain and numbness. He was fortunate to have leukoplakia and squamous cell carcinoma – photographs of common type of salivary gland tumour is the pleomorphic systemic causes. ese dierent diseases may present with not sought treatment as it had not caused any pain. -

Mandibular Tori

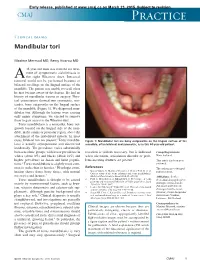

Early release, published at www.cmaj.ca on March 23, 2015. Subject to revision. CMAJ Practice Clinical images Mandibular tori Maxime Mermod MD, Remy Hoarau MD 44-year-old man was referred for treat- ment of symptomatic sialolithiasis in A the right Wharton duct. Intraoral removal could not be performed because of bilateral swellings on the lingual surface of the mandible. The patient was unable to recall when he first became aware of the lesions. He had no history of mandibular trauma or surgery. Phys- ical examination showed two symmetric, non- tender, bony outgrowths on the lingual surface of the mandible (Figure 1). We diagnosed man- dibular tori. Although the lesions were causing only minor symptoms, we elected to remove them to gain access to the Wharton duct. Torus mandibularis is a nontender, bony out- growth located on the lingual side of the man- dible, in the canine or premolar region, above the attachment of the mylohyoid muscle. In most 1 cases, bilateral tori are present. Torus mandibu- Figure 1: Mandibular tori are bony outgrowths on the lingual surface of the laris is usually asymptomatic and discovered mandible, often bilateral and symmetric, as in this 44-year-old patient. incidentally. The prevalence varies substantially between ethnic groups, with lower prevalence in resection is seldom necessary, but is indicated Competing interests: whites (about 8%) and blacks (about 16%) and when ulceration, articulation disorder or prob- None declared. higher prevalence in Asian and Inuit popula- lems inserting dentures are present.3 This article has been peer tions.2 Torus mandibularis is slightly more com- reviewed. -

Abscesses Apicectomy

BChD, Dip Odont. (Mondchir.) MBChB, MChD (Chir. Max.-Fac.-Med.) Univ. of Pretoria Co Reg: 2012/043819/21 Practice.no: 062 000 012 3323 ABSCESSES WHAT IS A TOOTH ABSCESS? A dental/tooth abscess is a localised acute infection at the base of a tooth, which requires immediate attention from your dentist. They are usually associated with acute pain, swelling and sometimes an unpleasant smell or taste in the mouth. More severe infections cause facial swelling as the bacteria spread to the nearby tissues of the face. This is a very serious condition. Once the swelling begins, it can spread rapidly. The pain is often made worse by drinking hot or cold fluids or biting on hard foods and may spread from the tooth to the ear or jaw on the same side. WHAT CAUSES AN ABSCESS? Damage to the tooth, an untreated cavity, or a gum disease can cause an abscessed tooth. If the cavity isn’t treated, the inside of the tooth can become infected. The bacteria can spread from the tooth to the tissue around and beneath it, creating an abscess. Gum disease causes the gums to pull away from the teeth, leaving pockets. If food builds up in one of these pockets, bacteria can grow, and an abscess may form. An abscess can cause the bone around the tooth to dissolve. WHY CAN'T ANTIBIOTIC TREATMENT ALONE BE USED? Antibiotics will usually help the pain and swelling associated with acute dental infections. However, they are not very good at reaching into abscesses and killing all the bacteria that are present. -

Susan Mcmahon, DMD AAACD Modern Adhesive Dentistry: Real World Esthetics for Presentation and More Info from Catapult Education

Susan McMahon, DMD AAACD Modern Adhesive Dentistry: Real World Esthetics For presentation and more info from Catapult Education Text SusanM to 33444 Susan McMahon DMD • Accredited by the American Academy of Cosmetic Dentistry: One of only 350 dentists worldwide to achieve this credential • Seven times named among America’s Top Cosmetic Dentists, Consumers Research Council of America • Seven time medal winner Annual Smile Gallery American Academy of Cosmetic Dentistry • Fellow International Academy Dental-Facial Esthetics • International Lecturer and Author Cosmetic Dental Procedures and Whitening Procedures • Catapult Education Elite, Key Opinion Leaders Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania Cosmetic dentistry is comprehensive oral health care that combines art and science to optimally improve dental health, esthetics, and function.” Why Cosmetic Dentistry? Fun Success dependent upon many disciplines Patients desire Variety cases/materials services Insurance free Professionally rewarding Financially rewarding Life changing for Artistic! patients “Adolescents tend to be strongly concerned about their faces and bodies because they wish to present a good physical appearance. Moreover, self-esteem is considered to play an important role in psychological adjustment and educational success” Di Biase AT, Sandler PJ. Malocclusion, Orthodontics and Bullying, Dent Update 2001;28:464-6 “It has been suggested that appearance dissatisfaction can lead to feelings of depression, loneliness and low self-esteem among other psychological outcomes.” Nazrat MM, Dawnavan -

Review: Differential Diagnosis of Drug-Induced Gingival Hyperplasia and Other Oral Lesions

ISSN: 2469-5734 Moshe. Int J Oral Dent Health 2020, 6:108 DOI: 10.23937/2469-5734/1510108 Volume 6 | Issue 2 International Journal of Open Access Oral and Dental Health REVIEW ARTICLE Review: Differential Diagnosis of Drug-Induced Gingival Hyper- plasia and Other Oral Lesions Einhorn Omer Moshe* Private Dental Office, Israel Check for *Corresponding author: Einhorn Omer Moshe, Private Dental Office, Dr. Einhorn, 89 Medinat Hayehudim updates street, Herzliya, Israel tooth discoloration, alteration of taste sensation and Abstract even appearance of lesions on the tissues of the oral Chronic medication usage is a major component of the cavity. Early recognition and diagnosis of these effects medical diagnosis of patients. Nowadays, some of the most common diseases such as cancer, hypertension, diabetes can largely assist in the prevention of further destruc- and etc., are treated with drugs which cause a variety of oral tive consequences in patients’ health status. As life ex- side-effects including gingival over growth and appearance pectancy increases, the number of elderly patients in of lesions on the tissues of the oral cavity. As such, drug-in- the dental practice also rises. Individuals of this popula- duced oral reactions are an ordinary sight in the dental prac- tice. This review will point out the main therapeutic agents tion are usually subjected to chronic medication intake causing gingival hyperplasia and other pathologic lesions which requires the clinician to be aware of the various in the oral cavity. Some frequently used medications, in side-effects accompanying these medications. This re- particular antihypertensives, nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory view will point out the main therapeutic agents causing drugs and even antibiotics, can lead to overgrowth of the gingival hyperplasia and other pathologic lesions in the gingiva and to the multiple unwanted conditions, namely: Lupus erythematosus, erythema multiforme, mucositis, oral oral cavity. -

Recognition and Management of Oral Health Problems in Older Adults by Physicians: a Pilot Study

J Am Board Fam Pract: first published as 10.3122/jabfm.11.6.474 on 1 November 1998. Downloaded from BRIEF REPORTS Recognition and Management of Oral Health Problems in Older Adults by Physicians: A Pilot Study Thomas V. Jones, MD, MPH, Mitchel J Siegel, DDS, andJohn R. Schneider, A1A Oral health problems are among the most com of the nation's current and future health care mon chronic health conditions experienced by needs, the steady increase in the older adult popu older adults. Healthy People 2000, an initiative to lation, and the generally high access elderly per improve the health of America, has selected oral sons have to medical care provided by family health as a priority area. l About 11 of 100,000 physicians and internists.s,7,8 Currently there is persons have oral cancer diagnosed every year.2 very little information about the ability of family The average age at which oral cancer is diagnosed physicians or internists, such as geriatricians, to is approximately 65 years, with the incidence in assess the oral health of older patients. We con creasing from middle adulthood through the sev ducted this preliminary study to determine how enth decade of life. l-3 Even though the mortality family physicians and geriatricians compare with rate associated with oral cancer (7700 deaths an each other and with general practice dentists in nually)4 ranks among the lowest compared with their ability to recognize, diagnose, and perform other cancers, many deaths from oral cancer initial management of a wide spectrum of oral might be prevented by improved case finding and health problems seen in older adults. -

Journal of the Irish Dental Association Iris Cumainn Déadach Na Héireann

Volume 55 Number 4 August/September 2009 Journal of the Irish Dental Association Iris Cumainn Déadach na hÉireann AN EFFECTIVE BLEACHING TECHNIQUE FOR NON-VITAL DISCOLOURED TEETH IN CHILDREN AND ADOLESCENTS Journal of the Irish Dental Association The Journal of the Irish Dental Association CONTENTS Unit 2 Leopardstown Office Park Sandyford, Dublin 18 Tel +353 1 295 0072 Fax: +353 1 295 0092 www.dentist.ie 161 EDITORIAL IDA PRESIDENT Dr Donal Blackwell IDA CHIEF EXECUTIVE Fintan Hourihan JOURNAL CO-ORDINATOR Fionnuala O’Brien 162 PRESIDENT’S NEWS EDITOR Professor Leo F.A. Stassen Fighting back FRCS(Ed), FDSRCS, MA, FTCD, FFSEM(UK) FFDRCSI DEPUTY EDITOR Dr Dermot Canavan BDentSc, MGDS(Edin), MS(UCalif) 163 IDA NEWS An Bord Snip Nua Report, upcoming IDA EDITORIAL BOARD Dr Tom Feeney meetings, and more BDS Dip Cl Dent(TCD) FICD Dr Michael Fenlon James, Ger and Niamh treating PhD BDentSc MA FDS MGDS kids in the clinic. 174 167 QUIZ Dr Aislinn Machesney BDentSc, DipClinDent Dr Christine McCreary MA MD FDS(RCPS)OM FFD(RCSI) 168 BUSINESS NEWS 6% Dr Ioannis Polyzois Industry news for dentists 12% DMD, MDentCh, MMedSc Dr Ciara Scott BDS MFD MDentCh MOrth FFD (RCSI) 171 EU NEWS Carmen Sheridan 31% MA ODE (Open), Dip Ad Ed, CDA, RDN CED independence likely by end of 2009 The Journal of the Irish Dental Association is the 23% official publication of the Irish Dental Association. 174 OVERSEAS The opinions expressed in the Journal are, however, those of the authors and cannot be construed as 174 Busman’s holiday Survey of dentists. -

Oral Health for USMLE Step One Section 3: Congenital, Salivary, Dental and Other Oral Pathology

Oral Health for USMLE Step One Section 3: Congenital, Salivary, Dental and Other Oral Pathology Olivia Nuelle, Medical School Class of 2022 University of Massachusetts Medical School Faculty Adviser: Hugh Silk, MD Image: Simone van den Berg/Photos.comE-mail: SmilesHoward@12DaysinMarch for Life Module 7 Slide # 1 smilesforlifeoralhealth.org www.12DaysinMarch.com Oral Health for USMLE Step One Pathology of the Oral Cavity Lesions Congenital Salivary Dental Other Pathology Pathology 1. Sialadenitis 1. Erosion 1. TMJ 1. Infection 1. GERD 2. Medications 2. Obstruction 2. Bulimia w/ Oral 2. Tumors 3. Bacteria Effects 1. Benign 2. Caries 3. SBE 2. Malignant 3. Abscess Prophylaxis Dental Pathology: Erosions Dental Pathology: Erosions • GERD • Bulimia • Bacteria Gastric acid • Cold and heat sensitivity • Pain Dental Pathology: Erosions Bulimia • Bottom teeth eroded • Parotitis • Russell’s sign. Gastric acid Russell’s sign Dental Pathology: Erosions → Caries Bacteria • Eat sugarà bacteria metabolizeà acid Dental Pathology: Caries Caries • S. mutans Dental Pathology: Abscess Abscess • Purulent infection • Pulp is infected • Potential for spread Oral Health for USMLE Step One Pathology of the Oral Cavity Lesions Congenital Salivary Dental Other Pathology Pathology 1. TMJ 2. Medications w/ Oral Effects 3. SBE Prophylaxis Oral Pathology: TMJ (temporomandibular joint syndrome) TMJ • Pain • Stiffness • Clicking Etiologies • Malalignment • Trauma • Bruxism Oral Manifestations of Medications Manifestations • Tooth discoloration • Gingival hyperplasia Oral -

Adverse Effects of Medications on Oral Health

Adverse Effects of Medications on Oral Health Dr. James Krebs, BS Pharm, MS, PharmD Director of Experiential Education College of Pharmacy, University of New England Presented by: Rachel Foster PharmD Candidate, Class of 2014 University of New England October 2013 Objectives • Describe the pathophysiology of various medication-related oral reactions • Recognize the signs and symptoms associated with medication-related oral reactions • Identify the populations associated with various offending agents • Compare the treatment options for medication-related oral reactions Medication-related Oral Reactions • Stomatitis • Oral Candidiasis • Burning mouth • Gingival hyperplasia syndrome • Alterations in • Glossitis salivation • Erythema • Alterations in taste Multiforme • Halitosis • Oral pigmentation • Angioedema • Tooth discoloration • Black hairy tongue Medication-related Stomatitis • Clinical presentation – Aphthous-like ulcers, mucositis, fixed-drug eruption, lichen planus1,2 – Open sores in the mouth • Tongue, gum line, buccal membrane – Patient complaint of soreness or burning http://www.virtualmedicalcentre.com/diseases/oral-mucositis-om/92 0 http://www.virtualmedicalcentre.com/diseases/oral-mucositis-om/920 Medication-related Stomatitis • Offending agents1,2 Medication Indication Patient Population Aspirin •Heart health • >18 years old •Pain reliever • Cardiac patients NSAIDs (i.e. Ibuprofen, •Headache General population naproxen) •Pain reliever •Fever reducer Chemotherapy (i.e. •Breast cancer •Oncology patients methotrexate, 5FU, •Colon