Money: Cultural Transactions Between Philip Larkin and Martin Amis

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

PDF Download Further Requirements: Interviews

FURTHER REQUIREMENTS: INTERVIEWS, BROADCASTS, STATEMENTS AND REVIEWS, 1952-85 PDF, EPUB, EBOOK Philip Larkin,Anthony Thwaite | 416 pages | 04 Nov 2002 | FABER & FABER | 9780571216147 | English | London, United Kingdom Further Requirements: Interviews, Broadcasts, Statements and Reviews, 1952-85 PDF Book When you have read it, take me by the hand As children do, loving simplicity. Shopbop Designer Modemarken. In Thwaite's poems there is rarely much in the way of display and few extravagant local effects. Geben Sie Feedback zu dieser Seite. Andere Formate: Gebundenes Buch , Taschenbuch. Cookies akzeptieren Cookie-Einstellungen anpassen. Thwaite is also an accomplished comic poet. Author statement 'If I could sum up my poetry in a few well-chosen words, the result might be a poem. Entdecken Sie jetzt alle Amazon Prime-Vorteile. Poetry and What is Real. Philip Larkin remains England's best-loved poet - a writer matchlessly capable of evoking his native land and of touching all readers from the most sophisticated intellectual to the proverbial common reader. Etwas ist schiefgegangen. Next page. Weitere Informationen bei Author Central. Philip Larkin. Anthony Thwaite. While Larkin views them in terms of the personal life, or at most, of England, Thwaite, who has travelled widely and worked overseas for extended periods, can also find them in an alien setting, for example in North Africa. Previous page. Artists, cultural professionals and art collective members in the UK and Southeast A… 1 days ago. Sind Sie ein Autor? Urbane, weary, aphoristic, certain that nothing and everything changes, the poems draw both on Cavafy and Lawrence Durrell. This entirely new edition brings together all of Philip Larkin's poems. -

Call No. Responsibility Item Publication Details Date Note 1

Call no. Responsibility Item Publication details Date Note TKNC0001 Roberts, H. Song, to a gay measure Dublin: printed at the Dolmen 1951 "200 copies." Neville Press TKNC0002 Promotional notice for Travelling tinkers, a book of Dolmen Press ballads by Sigerson Clifford TKNC0003 Promotional notice for Freebooters by Mauruce Kennedy Dolmen Press TKNC0004 Advertisement for Dolmen Press Greeting cards &c Dolmen Press TKNC0005 The reporter: the magazine of facts and ideas. Volume July 16, 1964 contains 'In the 31 no. 2 beginning' (verse) by Thomas Kinsella TKNC0006 Clifford, Travelling tinkers Dublin: Dolmen Press 1951 Of one hundred special Sigerson copies signed by the author this is number 85. Insert note from Thomas Kinsella. TKNC0007 Kinsella, Thomas The starlit eye / Thomas Kinsella ; drawings by Liam Dublin: Dolmen Press 1952 Set and printed by hand Miller at the Dolmen Press, Dublin, in an edition of 175 copies. March 1952. (p. [8]). TKNC0008 Kinsella, Thomas Galley proof of Poems [Glenageary, County Dublin]: 1956 Galley proof Dolmen Press TKNC0009 Kinsella, Thomas The starlit eye / Thomas Kinsella ; drawings by Liam Dublin : Dolmen Press 1952 Of twenty five special Miller copies signed by the author this is number 20. Set and printed by hand at the Dolmen Press, Dublin, in an edition of 175 copies. March 1952. TKNC0010 Promotional postcard for Love Duet from the play God's Dolmen Press gentry by Donagh MacDonagh TKNC0011 Irish writing. No. 24 Special issue - Young writers issue Dublin Sep-53 1 Thomas Kinsella Collection Listing Call no. Responsibility Item Publication details Date Note TKNC0012 Promotional notice for Dolmen Chapbook 3, The perfect Dolmen Press 1955 wife a fable by Robert Gibbings with wood engravings by the author TKNC0013 Pat and Mick Broadside no. -

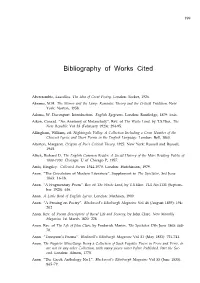

Bibliography of Works Cited

199 Bibliography of Works Cited Abercrombie, Lascelles. The Idea of Great Poetry. London: Secker, 1926. Abrams, M.H. The Mirror and the Lamp: Romantic Theory and the Critical Tradition. New York: Norton, 1958. Adams, W. Davenport. Introduction. English Epigrams. London: Routledge, 1879: i-xix. Aiken, Conrad. “An Anatomy of Melancholy”. Rev. of The Waste Land, by T.S.Eliot. The New Republic Vol 33 (February 1923): 294-95. Allingham, William, ed. Nightingale Valley: A Collection Including a Great Number of the Choicest Lyrics and Short Poems in the English Language. London: Bell, 1860. Alterton, Margaret. Origins of Poe’s Critical Theory. 1925. New York: Russell and Russell, 1965. Altick, Richard D. The English Common Reader. A Social History of the Mass Reading Public of 1800-1900. Chicago: U of Chicago P, 1957. Amis, Kingsley. Collected Poems 1944-1979. London: Hutchinson, 1979. Anon. “The Circulation of Modern Literature”. Supplement to The Spectator, 3rd June 1863: 16-18. Anon. “A Fragmentary Poem”. Rev of The Waste Land, by T.S.Eliot. TLS No.1131 (Septem- ber 1923): 616. Anon. A Little Book of English Lyrics. London: Methuen, 1900. Anon. “A Prosing on Poetry”. Blackwood’s Edinburgh Magazine Vol 46 (August 1839): 194- 202. Anon. Rev. of Poems Descriptive of Rural Life and Scenery, by John Clare. New Monthly Magazine 1st March 1820: 228 Anon. Rev. of The Life of John Clare, by Frederick Martin. The Spectator 17th June 1865: 668- 70. Anon. “Tennyson’s Poems”. Blackwell’s Edinburgh Magazine Vol 31 (May 1832): 721-741. Anon. The Fugitive Miscellany: Being a Collection of Such Fugitive Pieces in Prose and Verse, as are not in any other Collection, with many pieces never before Published. -

1. Philip Larkin

Notes References to material held in the Philip Larkin Archive lodged in the Brynmor Jones Library, University of Hull (BJL), are given as file numbers preceded by 'DPL'. 1. PHILIP LARKIN 1. Harry Chambers, 'Meeting Philip Larkin', in Larkin at Sixty, ed. Anthony Thwaite (London: Faber and Faber, 1982) p. 62. 2. John Haffenden, Viewpoints: Poets in Conversation (London, Faber and Faber, 1981) p. 127. 3. Christopher Ricks, Beckett's Dying Words (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1993). 4. D. J. Enright, 'Down Cemetery Road: the Poetry of Philip Larkin', in Conspirators and Poets (London: Chatto & Windus, 1966) p. 142. 5. Hugo Roeffaers, 'Schriven tegen de Verbeelding', Streven, vol. 47 (December 1979) pp. 209-22. 6. Andrew Motion, Philip Larkin: A Writer's Life (London: Faber and Faber, 1993). 7. Philip Larkin, Required Writing (London: Faber and Faber, 1983) p. 48. 8. See Selected Letters of Philip Larkin 1940-1985, ed. Anthony Thwaite (London: Faber and Faber, 1992) pp. 648-9. 9. DPL 2 (in BJL). 10. DPL 5 (in BJL). 11. Kingsley Amis, Memoirs (London: Hutchinson, 1991) p. 52. 12. Philip Larkin, Introduction to Jill (London: The Fortune Press, 1946; rev. edn. Faber and Faber, 1975) p. 12. 13. Donald Davie, Thomas Hardy and British Poetry (London: Routledge & Kegan Paul, 1973) p. 64. 14. Required Writing, p. 297. 15. Blake Morrison, 'In the grip of darkness', The Times Literary Supplement, 14-20 October 1988, p. 1152. 16. Lisa Jardine, 'Saxon violence', Guardian, 8 December 1992. 17. Bryan Appleyard, 'The dreary laureate of our provincialism', Independent, 18 March 1993. 18. Ian Hamilton, 'Self's the man', The Times Literary Supplement, 2 April 1993, p. -

Yorkshire Poetry, 1954-2019: Language, Identity, Crisis

YORKSHIRE POETRY, 1954-2019: LANGUAGE, IDENTITY, CRISIS Kyra Leigh Piperides Jaques, BA (Hons) and MA, (Hull) PhD University of York English & Related Literature October 2019 This work was supported by the Arts & Humanities Research Council (grant number AH/L503848/1) through the White Rose College of the Arts & Humanities. ABSTRACT This thesis explores the writing of a large selection of twentieth- and twenty-first- century East and West Yorkshire poets, making a case for Yorkshire as a poetic place. The study begins with Philip Larkin and Ted Hughes, and concludes with Simon Armitage, Sean O’Brien and Matt Abbott’s contemporary responses to the EU Referendum. Aside from arguing the significance of Yorkshire poetry within the British literary landscape, it presents poetry as a central form for the region’s writers to represent their place, with a particular focus on Yorkshire’s languages, its identities and its crises. Among its original points of analysis, this thesis redefines the narrative position of Larkin and scrutinizes the linguistic choices of Hughes; at the same time, it identifies and explains the roots and parameters of a fascinating new subgenre that is emerging in contemporary West Yorkshire poetry. This study situates its poems in place whilst identifying the distinct physical and social geographies that exist, in different ways, throughout East and West Yorkshire poetry. Of course, it interrogates the overarching themes that unite the two regions too, with emphasis on the political and historic events that affected the region and its poets, alongside the recurring insistence of social class throughout many of the poems studied here. -

Herein Is a Testament to Them Both

Spring 2012 Bertram Rota Ltd 31 LONG ACRE COVENT GARDEN, LONDON WC2E 9LT Telephone: + 44 (0) 20 7836 0723 * Fax: + 44 (0) 20 7497 9058 E-mail: [email protected] www.bertramrota.co.uk A Selection from the Library of Anthony and Ann Thwaite, including the Anthony Thwaite Philip Larkin collection Catalogue 307 Established 1923 TERMS OF BUSINESS. The items in this catalogue are offered at net sterling prices, for cash upon receipt. Charges for postage and packing will be added. All books are insured in transit. PAYMENT. We accept cheques and debit and credit cards (please quote the card number, start and expiry date and 3 digit security code as well as your name and address). For direct transfers: HSBC, 129 New Bond Street, London, W1A 2JA, sort code 40 05 01, account number 50149489 . VAT is added and charged on autograph letters and manuscripts (unless bound in the form of a book), drawings, prints and photographs WANTS LISTS. We are pleased to receive lists of books especially wanted. They are given careful attention and quotations are submitted without charge. We also provide valuations of books, manuscripts, archives and entire libraries. HOURS OF BUSINESS. We are open from 10 .30 to 6.0 0 from Monday to Friday. Appointment recommended. Unless otherwise described, all the books in this catalogue are published in London, in the original cloth or board bindings, octavo or crown octavo in size. Dust-wrappers should be assumed to be present only when specifically mentioned. We are delighted and proud to offer this selection, which includes a wealth of fine Presentation and Association Copies. -

Blackwell's Rare Books

BLACKWELL’S RARE BOOKS 1 Front cover image: Item 81 Blackwell’s Rare Books Rear cover image: Item 75 Telephone: +44 (0) 1865 333555 Internal image: Item 29 Switchboard: +44 (0) 1865 792792 Email: [email protected] Please2 mention Heaney catalogue when ordering www.blackwell.co.uk/rarebooks 1. Heaney (Seamus) Eleven Poems. Belfast: Festival Publications, Queen’s University of Belfast, [1967,] FIRST EDITION, third issue, a tiny spot at head of a couple of pages, pp. [15], crown 8vo, original stapled green wrappers, a couple of tiny water-spots to margin of front, very good (Brandes & Durkan A1c) £900 The author’s first book - though without mark of ownership, this formerly belonged to Heaney’s friend, Peterloo Poets founder Harry Chambers. 2. Heaney (Seamus) Death of a Naturalist. Faber and Faber, 1966, FIRST EDITION, pp. 57, crown 8vo, original green cloth, backstrip lettered in gilt, a couple of faint and tiny spots at head of front endpapers, dustjacket with the pink panel lightly faded, a little rubbed at front flap-fold, very good (Brandes & Durkan A2a) £3,000 Signed by the author to the title-page. An excellent copy. 3. Heaney (Seamus) Death of a Naturalist. Faber and Faber, 1966, FIRST EDITION, pp. 57, crown 8vo, original green cloth, backstrip lettered in gilt, a few faint spots to edges and front endpapers, dustjacket with some minor dustsoiling and spotting, pink to backstrip panel faded, a little rubbed and chipped with the odd nick, good (Brandes & Durkan A2a) £1,800 Signed by the author to the title-page. 4. -

Philip Larkin Also by James Booth

Philip Larkin Also by James Booth NEW LARKINS FOR OLD: Critical Essays (ed.) PHILIP LARKIN: Writer SYLLOGE OF COINS OF THE BRITISH ISLES 48: Northern Museums TROUBLE AT WILLOW GABLES AND OTHER FICTIONS by Philip Larkin (ed.) WRITERS AND POLITICS IN NIGERIA Philip Larkin The Poet’s Plight by James Booth © James Booth 2005 Softcover reprint of the hardcover 1st edition 2005 978-1-4039-1834-5 All rights reserved. No reproduction, copy or transmission of this publication may be made without written permission. No paragraph of this publication may be reproduced, copied or transmitted save with written permission or in accordance with the provisions of the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act 1988, or under the terms of any licence permitting limited copying issued by the Copyright Licensing Agency, 90 Tottenham Court Road, London W1T 4LP. Any person who does any unauthorised act in relation to this publication may be liable to criminal prosecution and civil claims for damages. The author has asserted his rights to be identified as the author of this work in accordance with the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act 1988. First published 2005 by PALGRAVE MACMILLAN Houndmills, Basingstoke, Hampshire RG21 6XS and 175 Fifth Avenue, New York, N. Y. 10010 Companies and representatives throughout the world PALGRAVE MACMILLAN is the global academic imprint of the Palgrave Macmillan division of St. Martin’s Press, LLC and of Palgrave Macmillan Ltd. Macmillan® is a registered trademark in the United States, United Kingdom and other countries. Palgrave is a registered trademark in the European Union and other countries. ISBN 978-1-349-51417-5 ISBN 978-0-230-59582-8 (eBook) DOI 10.1057/9780230595828 This book is printed on paper suitable for recycling and made from fully managed and sustained forest sources. -

These Ghostly Archives

Plath Profiles 183 These Ghostly Archives Gail Crowther, Lancaster University & Peter K. Steinberg Why do some people, including myself, enjoy in certain novels, biographies and historical works the representation of “daily life” of an epoch, of a character? Why this curiosity about petty details: schedules, habits, meals, lodgings, clothing etc? Is it the hallucinatory relish of “reality” (the very materiality of “that once existed”)? And is it not the fantasy itself which invokes the “detail”, the tiny private scene in which I can easily take my place? Roland Barthes (1975) Archives are very magical places. Carolyn Steedman (2001) describes how archives are full of dust. Dust of long gone eras and people, dust of the past. Carrying out archival work for Sylvia Plath studies is especially magical. As Barthes states above, we can indulge our curiosity for petty details, we can understand the more practical side of Plath sending poems and letters to magazines. We can see the day-to-day life of a writer, the manuscripts, the drafts, the rejections, the triumphs, and the odd and curious glimpses into a domestic life running parallel to the writer’s life. The following will explore the experiences of two Plath archival professionals. Peter K. Steinberg’s work carried out in Smith College, in America, and Gail Crowther’s work in the BBC Written Archives Centre in England. It aims to show the excitement of planning archival work, the thrill of handling original documents, the utter joy of finding small unpublished details. We wrote this paper in the spirit of what Anita Helle proposes in “Archival Matters”, “Research on Plath is not conducted merely to produce new academic commodities – it is conducted out of love for her Crowther & Steinberg 184 writing and a desire to do justice to the complexity of her art.” 1 We also aim to show how working in an archive impacts the researcher. -

978–0–230–34824–0 Copyrighted Material

Copyrighted material – 978–0–230–34824–0 © John Osborne 2014 All rights reserved. No reproduction, copy or transmission of this publication may be made without written permission. No portion of this publication may be reproduced, copied or transmitted save with written permission or in accordance with the provisions of the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act 1988, or under the terms of any licence permitting limited copying issued by the Copyright Licensing Agency, Saffron House, 6–10 Kirby Street, London EC1N 8TS. Any person who does any unauthorized act in relation to this publication may be liable to criminal prosecution and civil claims for damages. The author has asserted his right to be identified as the author of this work in accordance with the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act 1988. First published 2014 by PALGRAVE MACMILLAN Palgrave Macmillan in the UK is an imprint of Macmillan Publishers Limited, registered in England, company number 785998, of Houndmills, Basingstoke, Hampshire RG21 6XS. Palgrave Macmillan in the US is a division of St Martin’s Press LLC, 175 Fifth Avenue, New York, NY 10010. Palgrave Macmillan is the global academic imprint of the above companies and has companies and representatives throughout the world. Palgrave® and Macmillan® are registered trademarks in the United States, the United Kingdom, Europe and other countries. ISBN 978–0–230–34824–0 This book is printed on paper suitable for recycling and made from fully managed and sustained forest sources. Logging, pulping and manufacturing processes are expected to conform to the environmental regulations of the country of origin. A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library. -

Robert Browning and Mick Imlah: Forming and Collecting the Dramatic Monologue

Robert Browning and Mick Imlah: Forming and Collecting the Dramatic Monologue John Morton One could be forgiven for thinking that the young but very active field of neo-Victorian studies is exclusively concerned with fictional and filmed narratives. However, just as the poetry of the Victorian age resonates in the most unlikely of places, from films such as Hellboy 2 (2008) and Skyfall (2012), both of which feature readings from Tennyson, to the extract from Tennyson’s “Ulysses” reproduced on the wall of the London 2012 Olympic Village,1 so it endures in contemporary poetry, both in quotation but also in terms of form. Contemporary poets, not least Carol Ann Duffy, have returned in a general way to one of the poetical forms (if it can be termed a form) most associated with the Victorians, the dramatic monologue. The two poets I will focus on in this article Mick Imlah, along with the older Anthony Thwaite, neither of whom has had a great deal of academic attention paid to their work until now,2 come to the act of writing and collecting the Browningesque dramatic monologue from a standpoint which in recent years has been specifically defined as neo- Victorian by critics such as Ann Heilmann, Mark Llewellyn, and Marie-Luise Kohlke. In assessing their neo-Victorian returns to the composition and collection of dramatic monologues, I will consider their engagement with the nineteenth-century tradition of focusing such poems on marginal figures, while maintaining a sense of self-awareness at the artificiality of the form. I will briefly consider how the dramatic monologue affords Thwaite the opportunity to voice figures from the Victorian past who might have disappeared forever before moving on to a longer study of how Imlah follows this model at times but also expands it to consider the interrelation of England (often represented by Oxford) and Scotland, and their literary and intellectual heritage. -

Thwaite, Anthony. Collected Poems. London

Book Reviews / Religion and the Arts 12 (2008) 602–629 623 Th waite, Anthony. Collected Poems. London: Enitharmon Press, 2007; Chester Springs PA: Dufour Editions, 2008. Pp. 448. £25.00, $66.95 cloth. ver the course of more than fi fty years, Anthony Th waite has sus- Otained a signifi cant outpouring of poems distinguished by their tech- nical control, metrical regularity, and striking originality. Avoiding the fl ashier trends of the last half-century, he has continued to produce a for- mal yet highly personal body of work. It is thus a rewarding pleasure to encounter Th waite’s poetry now collected, for the fi rst time in his career, in a substantive though not complete edition. Th e 380 personally selected poems in this volume comprise a survey of his individual books of poetry published between 1957 and 2003. Th is Collected Poems is a fi tting cap- stone for Th waite’s lifelong commitment to poetry, an encomium for a poet whose gifts are of the highest order. Th is is breathtaking and prodi- gious poetry, rooted in the British tradition yet entirely singular. Born in 1930, Anthony Th waite read English on scholarship at Christ Church, where he edited Isis and Oxford Poetry and presided over the Oxford Poetry Society. In a varied career he has worked as a BBC radio producer, as a publishing director at André Deutsch, as literary editor of the Listener and New Statesman, and as co-editor of Encounter. Th ough he has spent the majority of his life in England, Th waite has traveled widely, including teaching stints in Japan and Libya, and he is deeply interested in archaeology, editing Th e Ruins of Time: Antiquarian and Archaeological Poems (Eland) in 2006.