Leisure's Legacy

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

MEIEA 2014 Color.Indd

Journal of the Music & Entertainment Industry Educators Association Volume 14, Number 1 (2014) Bruce Ronkin, Editor Northeastern University Published with Support from Songs As Branding Platforms? A Historical Analysis of People, Places, and Products in Pop Music Lyrics Storm Gloor University of Colorado Denver Abstract Artists have become decidedly more accustomed to partnering with product marketers. Typically, though, the relationships have involved tour sponsorships, endorsements, or the use of the artist’s music in commer- cials. There are plenty of examples of using popular music in advertising. However, how often has there been advertising in popular music? Artists are in a sense “brands.” Many of them appear to promote or acquaint au- diences with their lifestyles through the music they create. Popular songs can serve not only as a mechanism for the subtle marketing of commer- cial consumer products, but also as a platform for marketing artists. Three types of branding devices are typically employed by songwriters: the men- tion of specific product brands, geographical places including cities and states, and well-known people (e.g., celebrities, cultural icons, and politi- cians). The aim of this study is to identify just how often these three types of lyrical references have occurred in popular songs through the years. How frequently have popular songs employed lyrics that may be serving the purpose of branding or advertising consumer products or the artists themselves, and are there observable trends regarding the practice over -

Ron Thomas Coming to the Hard Rock Live

Ron Thomas coming to the Hard Rock Live Hollywood, Fla. – Grammy Award-winning singer and songwriter Rob Thomas will bring his North American tour to Hard Rock Live at Seminole Hard Rock Hotel & Casino on Friday, Oct. 23, at 8 p.m. Tickets go on sale Friday, Aug. 7, at 10 a.m. Fans will have access to presale tickets beginning Thursday, Aug. 6, at 10 a.m. through Seminole Hard Rock Hollywood’s Facebook andTwitter pages. Rob Thomas is one of the most distinctive artists of this or any other era – a gifted vocalist, spellbinding performer and accomplished songwriter known worldwide as lead singer and primary composer with Matchbox Twenty, as well as for his multi-platinum certified solo work and chart-topping collaborations with other artists. Among his countless hits are solo classics like “Lonely No More,” “This Is How A Heart Breaks” and “Streetcorner Symphony,” Matchbox Twenty favorites including “Push,” “3AM,” “If You’re Gone” and “Bent,” and, of course “Smooth,” his 3x RIAA platinum certified worldwide hit collaboration with Santana. Thomas earned three Grammy Awards for his role as co-writer and vocalist on “Smooth,” which topped Billboard’s “Hot 100” for an astounding 12 consecutive weeks and spent 58 total weeks on the chart, the No. 1 song in Billboard’s Top Hot 100 Rock Songs chart history and No. 2 Hot 100 song of all time. The No.1, multi-platinum “… Something to Be,” made history as the first album by a male artist from a rock or pop group to debut at No. -

Songs About Fathers and Their Children Content: #10 “RAINCOAT” – Kelly Sweet “IN TOO DEEP” – Genesis THEME: “DAUGHTERS” – John Mayer

Show Code: #07-24 Show Date: Weekend of June 16-17, 2007 Disc One/Hour One Opening Billboard: None Seg. 1 Track 1 THEME: Songs About Fathers and Their Children Content: #10 “RAINCOAT” – Kelly Sweet “IN TOO DEEP” – Genesis THEME: “DAUGHTERS” – John Mayer Commercials: :30 Bounty Mach 4 :30 National Assoc :30 Wal-Mart/$4 Gen :30 Sherwin William Outcue: “...ask Sherwin Williams.” (sung) Segment Time: 15:51 Local Break: 2:00 Seg. 2 Track 2 Content: #9 “CHANGE” – Kimberley Locke EXT: “THE REASON” – Hoobastank THEME: “MY FATHER’S EYES” – Eric Clapton “HIPS DON’T LIE” – Shakira Commercials: :30 Wal-Mart/$4 Gen :30 Match.com :30 Bounty Mach 4 :30 Walmart/Grillin Outcue: “...barbeques start here.” Segment time: 18:26 Local Break 2:00 Seg 3 Track 3 Content: “I DON’T WANNA FIGHT” – Tina Turner #8 “STREETCORNER SYMPHONY” – Rob Thomas THEME: “EVERYTHING I OWN” – Bread #7 “HURT” – Christina Aguilera Commercials: :30 Campbell's/Red :30 Wal-Mart/$4 Gen Outcue: “...for high prices.” Segment time: 17:02 Local Break 1:00 Seg 4 Track 4 ***This is an optional cut - Stations can opt to drop song for local inventory*** Content: AT10 Extra: “MRS. ROBINSON” – Simon & Garfunkel Outcue: “…film The Graduate.” NO JINGLE Segment time: 3:43 Hour 1 Total Time: 60:02 END OF DISC ONE ---- DISC TWO STARTS AT SEGMENT FIVE Show Code: #07-24 Show Date: Weekend of June 16-17, 2007 Disc Two/Hour Two Seg. 5 Track 1 Content: Insert Local ID over :06 jingle bed “ALL I WANNA DO IS MAKE LOVE TO YOU” – Heart #6 “FAR AWAY” – Nickelback THEME: “PAPA DON’T PREACH” – Madonna “TOO LATE TO TURN BACK NOW” – Cornelius Brothers & Sister Rose Commercials: :30 Walmart/Grillin :30 Geico Auto Insu :30 American Egg Bo :30 Wal-Mart/$4 Gen Outcue: “...for high prices.” Segment time: 18:43 Local Break 2:00 Seg. -

WHAT USE IS MUSIC in an OCEAN of SOUND? Towards an Object-Orientated Arts Practice

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by Oxford Brookes University: RADAR WHAT USE IS MUSIC IN AN OCEAN OF SOUND? Towards an object-orientated arts practice AUSTIN SHERLAW-JOHNSON OXFORD BROOKES UNIVERSITY Submitted for PhD DECEMBER 2016 Contents Declaration 5 Abstract 7 Preface 9 1 Running South in as Straight a Line as Possible 12 2.1 Running is Better than Walking 18 2.2 What You See Is What You Get 22 3 Filling (and Emptying) Musical Spaces 28 4.1 On the Superficial Reading of Art Objects 36 4.2 Exhibiting Boxes 40 5 Making Sounds Happen is More Important than Careful Listening 48 6.1 Little or No Input 59 6.2 What Use is Art if it is No Different from Life? 63 7 A Short Ride in a Fast Machine 72 Conclusion 79 Chronological List of Selected Works 82 Bibliography 84 Picture Credits 91 Declaration I declare that the work contained in this thesis has not been submitted for any other award and that it is all my own work. Name: Austin Sherlaw-Johnson Signature: Date: 23/01/18 Abstract What Use is Music in an Ocean of Sound? is a reflective statement upon a body of artistic work created over approximately five years. This work, which I will refer to as "object- orientated", was specifically carried out to find out how I might fill artistic spaces with art objects that do not rely upon expanded notions of art or music nor upon explanations as to their meaning undertaken after the fact of the moment of encounter with them. -

Billboard All-Time Adult Contemporary 1000 (Ms-Database Ver.) # C.I

Billboard All-Time Adult Contemporary 1000 (ms-database Ver.) # C.I. 10 Peak wks Peak Date Title Artist 1 124 64 1 17 1999/12/25 I Knew I Loved You Savage Garden 2 123 58 1 11 1998/04/11 Truly Madly Deeply Savage Garden 3 91 74 1 28 2003/06/07 Drift Away Uncle Kracker featuring Dobie Gray 4 94 75 1 11 2001/03/17 I Hope You Dance Lee Ann Womack 5 89 58 1 19 1999/05/29 You'll Be In My Heart Phil Collins 6 88 63 1 15 2001/12/08 Hero Enrique Iglesias 7 95 74 1 2 2001/10/06 If You're Gone matchbox twenty 8 77 67 1 18 2004/10/02 Heaven Los Lonely Boys 9 104 52 2 1 2000/10/07 I Need You LeAnn Rimes 10 92 51 2 5 2000/05/13 Amazed Lonestar 11 70 57 1 18 2005/08/20 Lonely No More Rob Thomas 12 87 58 2 8 2002/05/25 Superman (It's Not Easy) Five For Fighting 13 81 42 1 13 1996/08/10 Change The World Eric Clapton 14 70 50 1 17 2000/04/22 Breathe Faith Hill 15 64 57 1 19 2006/05/13 Bad Day Daniel Powter 16 63 52 1 22 2010/07/03 Hey, Soul Sister Train 17 81 54 1 4 2001/06/16 Thankyou Dido 18 60 52 1 24 2017/05/06 Shape Of You Ed Sheeran 19 81 42 1 8 1998/06/27 You're Still The One Shania Twain 20 82 36 1 12 1999/03/06 Angel Sarah McLachlan 21 85 51 1 1 1999/12/18 That's The Way It Is Celine Dion 22 64 48 1 21 2005/03/12 Breakaway Kelly Clarkson 23 77 47 1 6 2003/11/15 Forever And For Always Shania Twain 24 73 57 1 6 2001/09/29 Only Time Enya 25 58 52 1 20 2011/02/05 Just The Way You Are Bruno Mars 26 72 55 1 9 2006/01/21 You And Me Lifehouse 27 74 50 1 7 2002/09/21 A Thousand Miles Vanessa Carlton 28 57 54 1 18 2016/07/09 Can't Stop The Feeling! Justin -

Venturing in the Slipstream

VENTURING IN THE SLIPSTREAM THE PLACES OF VAN MORRISON’S SONGWRITING Geoff Munns BA, MLitt, MEd (hons), PhD (University of New England) A thesis submitted for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy of Western Sydney University, October 2019. Statement of Authentication The work presented in this thesis is, to the best of my knowledge and belief, original except as acknowledged in the text. I hereby declare that I have not submitted this material, either in full or in part, for a degree at this or any other institution. .............................................................. Geoff Munns ii Abstract This thesis explores the use of place in Van Morrison’s songwriting. The central argument is that he employs place in many of his songs at lyrical and musical levels, and that this use of place as a poetic and aural device both defines and distinguishes his work. This argument is widely supported by Van Morrison scholars and critics. The main research question is: What are the ways that Van Morrison employs the concept of place to explore the wider themes of his writing across his career from 1965 onwards? This question was reached from a critical analysis of Van Morrison’s songs and recordings. A position was taken up in the study that the songwriter’s lyrics might be closely read and appreciated as song texts, and this reading could offer important insights into the scope of his life and work as a songwriter. The analysis is best described as an analytical and interpretive approach, involving a simultaneous reading and listening to each song and examining them as speech acts. -

1 Nine 7 Days of Lonely 10,000 Maniacs More Than This

1 NINE 7 DAYS OF LONELY 10,000 MANIACS MORE THAN THIS 10,000 MANIACS BECAUSE THE NIGHT 10,000 MANIACS TROUBLE ME 10,000 MANIACS THESE ARE THE DAYS 100 PROOF AGED IN SOUL SOMEBODY'S BEEN SLEEPING 10CC 10CC 10CC I'M NOT IN LOVE 10CC THE THINGS WE DO FOR LOVE 112 IT'S OVER NOW 112 YOU ALREADY KNOW 112 ONLY YOU 112 DANCE WITH ME 112 CUPID 112 COME SEE ME 112 PEACHES AND CREAM 112 AND LUDACRIS HOT AND WET 112 AND SUPER CAT NA NA NA 12 GAUGE DUNKIE BUTT 1910 FRUIT GUM CO. 1, 2, 3, REDLIGHT 2 CHAINZ AND DRAKE NO LIE 2 CHAINZ AND KENDRICK LAMAR ASAP ROCKY DRAKEFUCKING PROBLEMS 2 LIVE CREW DO WAH DIDDY 2 LIVE CREW ME SO HORNY 2 LIVE CREW WE WANT SOME PUSSY! 2 PAC DEAR MAMA 2 PAC CHANGES 2 PAC THUGZ MANSION 2 PAC HOW DO YOU WANT IT 2 PAC CALIFORNIA LOVE 20 FINGERS SHORT DICK MAN 3 OH 3 AND KATY PERRY STARSTRUKK 30 SECONDS TO MARS THE KILL 311 CREATURES (FOR A WHILE) 311 AMBER 311 YOU WOULDN'T BELIEVE 311 ALL MIXED UP 311 DON'T TREAD ON ME 311 DOWN 311 LOVE SONG 38 SPECIAL CAUGHT UP IN YOU 38 SPECIAL WILD EYED SOUTHERN BOYS 38 SPECIAL ROCKIN' ONTO THE NIGHT 38 SPECIAL HOLD ON LOOSELY 38 SPECIAL IF I'D BEEN THE ONE 3OH3 DON'T TRUST ME 3RD STRIKE NO LIGHT 3T ANYTHING 3T TEASE ME 4 P.M. SUKIYAKI 4 P.M. LAY DOWN YOUR LOVE 4 RUNNER CAIN'S BLOOD 4 RUNNER THAT WAS HIM 5 STAIRSTEPS OOH CHILD 50 CENT HUSTLER'S AMBITION 50 CENT CANDY SHOP 50 CENT PIGGY BANK 50 CENT WHAT UP GANGSTA 50 CENT BEST FRIEND 50 CENT PIMP 50 CENT WANKSTA 50 CENT DISCO INFERNO 50 CENT IN DA CLUB 50 CENT AND EMINEM PATIENTLY WAITING 50 CENT AND MOBB DEEP OUTTA CONTROL 50 CENT AND NATE -

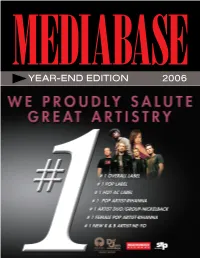

Year-End Edition 2006 Mediabase Overall Label Share 2006

MEDIABASE YEAR-END EDITION 2006 MEDIABASE OVERALL LABEL SHARE 2006 ISLAND DEF JAM TOP LABEL IN 2006 Atlantic, Interscope, Zomba, and RCA Round Out The Top Five Island Def Jam Music Group is this year’s #1 label, according to Mediabase’s annual year-end airplay recap. Led by such acts as Nickelback, Ludacris, Ne-Yo, and Rihanna, IDJMG topped all labels with a 14.1% share of the total airplay pie. Island Def Jam is the #1 label at Top 40 and Hot AC, coming in second at Rhythmic, Urban, Urban AC, Mainstream Rock, and Active Rock, and ranking at #3 at Alternative. Atlantic was second with a 12.0% share. Atlantic had huge hits from the likes of James Blunt, Sean Paul, Yung Joc, Cassie, and Rob Thomas -- who all scored huge airplay at multiple formats. Atlantic ranks #1 at Rhythmic and Urban, second at Top 40 and AC, and third at Hot AC and Mainstream Rock. Atlantic did all of this separately from sister label Lava, who actually broke the top 15 labels thanks to Gnarls Barkley and Buckcherry. Always powerful Interscope was third with 8.4%. Interscope was #1 at Alternative, second at Top 40 and Triple A, and fifth at Rhythmic. Interscope was led byAll-American Rejects, Black Eyed Peas, Fergie, and Nine Inch Nails. Zomba posted a very strong fourth place showing. The label group garnered an 8.0% market share, with massive hits from Justin Timberlake, Three Days Grace, Tool and Chris Brown, along with the year’s #1 Urban AC hit from Anthony Hamilton. -

Metaphoric and Metonymic Complexes in Phrasal Verb Interpretation Francisco José Ruiz De Mendoza Ibáñez and Alicia Galera-Masegosa 1-29

Language Value December 2011, Volume 3, Number 1 http://www.e-revistes.uji.es/languagevalue Copyright © 2011, ISSN 1989-7103 Table of Contents From the editors Antonio José Silvestre López, Mari Carmen Campoy Cubillo, and Miguel F. Ruiz Garrido i-vi Articles Going beyond metaphtonymy: Metaphoric and metonymic complexes in phrasal verb interpretation Francisco José Ruiz de Mendoza Ibáñez and Alicia Galera-Masegosa 1-29 Towards an integrated model of metaphorical linguistic expressions in English Ariadna Strugielska 30-48 Topological vs. lexical determination in English particle verbs (PVs) Renata Geld 49-75 Strategic construal of in and out in English particle verbs (PVs) Renata Geld and Ricardo Maldonado 76-113 Lexical decomposition of English prepositions and their fusion with verb lexical classes in motion constructions Ignasi Navarro i Ferrando 114-137 Analyses of the semantic features of the lexical bundle [(VERB) PREPOSITION the NOUN of] Siaw-Fong Chung, F.Y. August Chao, Tien-Yu Lan, and Yen-Yu Lin 138-152 Book and Multimedia Reviews Michael Rundell. Macmillan Collocations Dictionary for Learners of English Pedro A. Fuertes-Olivera 153-161 Terminology Management Systems for the development of (specialised) dictionaries: a focus on WordSmith Tools and Termstar XV Nuria Edo Marzá 162-173 Copyright © 2011 Language Value, ISSN 1989-7103. Articles are copyrighted by their respective authors Language Value December 2011, Volume 3, Number 1 pp. i-vi http://www.e-revistes.uji.es/languagevalue Copyright © 2011, ISSN 1989-7103 In Memoriam The journal editors and the Department of English Studies at the Universitat Jaume I wish to pay tribute to our colleague, friend and teacher, Dr. -

Practical Lessons and Resources for Teachers from Foundation to Year 10

Practical lessons and resources for teachers from Foundation to Year 10 Fostering Volunteering and the a culture Australian of giving Curriculum A National Innovation and Collaboration Project Volunteering ACT is proudly managed by Volunteering and Contact ACT. Volunteering and Contact ACT is funded by the Department of Social Services to implement the Fostering a Culture of Giving: Volunteering and the Australian Curriculum, a National Innovation and Collaboration project. August 2015 FOSTERING A CULTURE OF GIVING: VOLUNTEERING AND THE AUSTRALIAN CURRICULUM FOREWORD As our country’s peak body for volunteering, Volunteering Australia’s mission is to lead, strengthen, promote and celebrate volunteering. We encourage and support positive civic participation through volunteer service by people of all ages and from all walks of life. A key enabler in achieving our mission is the development of innovative, practical and accessible resources. We are extremely pleased therefore to welcome the publication of a new nationally significant resource, Volunteering and the Australian Curriculum – Fostering a Culture of Giving: Practical Lessons for Teachers from Foundation to Year 10. This resource was developed as one of a number of National Innovation and Collaboration Projects funded by the Federal Department of Social Services under its Families and Communities Program. Australia’s strong tradition of volunteering must continue to be promoted and strengthened in an ever-changing world. Opening up opportunities in the mainstream school setting for all young Australians to learn about volunteering and to embrace a culture of giving has the potential to set patterns for lifetime fulfilment, community connection and better health. There is strong research evidence that students’ active civic involvement supports their educational participation and achievement. -

Journal of Hip Hop Studies

et al.: Journal of Hip Hop Studies Published by VCU Scholars Compass, 2014 1 Journal of Hip Hop Studies, Vol. 1 [2014], Iss. 1, Art. 1 Editor in Chief: Daniel White Hodge, North Park University Book Review Editor: Gabriel B. Tait, Arkansas State University Associate Editors: Cassandra Chaney, Louisiana State University Jeffrey L. Coleman, St. Mary’s College of Maryland Monica Miller, Lehigh University Editorial Board: Dr. Rachelle Ankney, North Park University Dr. Jason J. Campbell, Nova Southeastern University Dr. Jim Dekker, Cornerstone University Ms. Martha Diaz, New York University Mr. Earle Fisher, Rhodes College/Abyssinian Baptist Church, United States Dr. Daymond Glenn, Warner Pacific College Dr. Deshonna Collier-Goubil, Biola University Dr. Kamasi Hill, Interdenominational Theological Center Dr. Andre Johnson, Memphis Theological Seminary Dr. David Leonard, Washington State University Dr. Terry Lindsay, North Park University Ms. Velda Love, North Park University Dr. Anthony J. Nocella II, Hamline University Dr. Priya Parmar, SUNY Brooklyn, New York Dr. Soong-Chan Rah, North Park University Dr. Rupert Simms, North Park University Dr. Darron Smith, University of Tennessee Health Science Center Dr. Jules Thompson, University Minnesota, Twin Cities Dr. Mary Trujillo, North Park University Dr. Edgar Tyson, Fordham University Dr. Ebony A. Utley, California State University Long Beach, United States Dr. Don C. Sawyer III, Quinnipiac University Media & Print Manager: Travis Harris https://scholarscompass.vcu.edu/jhhs/vol1/iss1/1 2 et al.: Journal of Hip Hop Studies Sponsored By: North Park Universities Center for Youth Ministry Studies (http://www.northpark.edu/Centers/Center-for-Youth-Ministry-Studies) . FO I ITH M I ,I T R T IDIE .ORT ~ PAru<.UN~V RSllY Save The Kids Foundation (http://savethekidsgroup.org/) 511<, a f't.dly volunteer 3raSS-roots or3an:za6on rooted :n h;,P ho,P and transf'orMat:ve j us6c.e, advocates f'or alternat:ves to, and the end d, the :nc..arc.eration of' al I youth . -

Songs by Artist

Songs by Artist Title Title (Hed) Planet Earth 2 Live Crew Bartender We Want Some Pussy Blackout 2 Pistols Other Side She Got It +44 You Know Me When Your Heart Stops Beating 20 Fingers 10 Years Short Dick Man Beautiful 21 Demands Through The Iris Give Me A Minute Wasteland 3 Doors Down 10,000 Maniacs Away From The Sun Because The Night Be Like That Candy Everybody Wants Behind Those Eyes More Than This Better Life, The These Are The Days Citizen Soldier Trouble Me Duck & Run 100 Proof Aged In Soul Every Time You Go Somebody's Been Sleeping Here By Me 10CC Here Without You I'm Not In Love It's Not My Time Things We Do For Love, The Kryptonite 112 Landing In London Come See Me Let Me Be Myself Cupid Let Me Go Dance With Me Live For Today Hot & Wet Loser It's Over Now Road I'm On, The Na Na Na So I Need You Peaches & Cream Train Right Here For You When I'm Gone U Already Know When You're Young 12 Gauge 3 Of Hearts Dunkie Butt Arizona Rain 12 Stones Love Is Enough Far Away 30 Seconds To Mars Way I Fell, The Closer To The Edge We Are One Kill, The 1910 Fruitgum Co. Kings And Queens 1, 2, 3 Red Light This Is War Simon Says Up In The Air (Explicit) 2 Chainz Yesterday Birthday Song (Explicit) 311 I'm Different (Explicit) All Mixed Up Spend It Amber 2 Live Crew Beyond The Grey Sky Doo Wah Diddy Creatures (For A While) Me So Horny Don't Tread On Me Song List Generator® Printed 5/12/2021 Page 1 of 334 Licensed to Chris Avis Songs by Artist Title Title 311 4Him First Straw Sacred Hideaway Hey You Where There Is Faith I'll Be Here Awhile Who You Are Love Song 5 Stairsteps, The You Wouldn't Believe O-O-H Child 38 Special 50 Cent Back Where You Belong 21 Questions Caught Up In You Baby By Me Hold On Loosely Best Friend If I'd Been The One Candy Shop Rockin' Into The Night Disco Inferno Second Chance Hustler's Ambition Teacher, Teacher If I Can't Wild-Eyed Southern Boys In Da Club 3LW Just A Lil' Bit I Do (Wanna Get Close To You) Outlaw No More (Baby I'ma Do Right) Outta Control Playas Gon' Play Outta Control (Remix Version) 3OH!3 P.I.M.P.