SEA Magazine Spring 2017 Editor-In-Chief Jason W. Kelly

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Building Cold War Warriors: Socialization of the Final Cold War Generation

BUILDING COLD WAR WARRIORS: SOCIALIZATION OF THE FINAL COLD WAR GENERATION Steven Robert Bellavia A Dissertation Submitted to the Graduate College of Bowling Green State University in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY May 2018 Committee: Andrew M. Schocket, Advisor Karen B. Guzzo Graduate Faculty Representative Benjamin P. Greene Rebecca J. Mancuso © 2018 Steven Robert Bellavia All Rights Reserved iii ABSTRACT Andrew Schocket, Advisor This dissertation examines the experiences of the final Cold War generation. I define this cohort as a subset of Generation X born between 1965 and 1971. The primary focus of this dissertation is to study the ways this cohort interacted with the three messages found embedded within the Cold War us vs. them binary. These messages included an emphasis on American exceptionalism, a manufactured and heightened fear of World War III, as well as the othering of the Soviet Union and its people. I begin the dissertation in the 1970s, - during the period of détente- where I examine the cohort’s experiences in elementary school. There they learned who was important within the American mythos and the rituals associated with being an American. This is followed by an examination of 1976’s bicentennial celebration, which focuses on not only the planning for the celebration but also specific events designed to fulfill the two prime directives of the celebration. As the 1980s came around not only did the Cold War change but also the cohort entered high school. Within this stage of this cohorts education, where I focus on the textbooks used by the cohort and the ways these textbooks reinforced notions of patriotism and being an American citizen. -

MEIEA 2014 Color.Indd

Journal of the Music & Entertainment Industry Educators Association Volume 14, Number 1 (2014) Bruce Ronkin, Editor Northeastern University Published with Support from Songs As Branding Platforms? A Historical Analysis of People, Places, and Products in Pop Music Lyrics Storm Gloor University of Colorado Denver Abstract Artists have become decidedly more accustomed to partnering with product marketers. Typically, though, the relationships have involved tour sponsorships, endorsements, or the use of the artist’s music in commer- cials. There are plenty of examples of using popular music in advertising. However, how often has there been advertising in popular music? Artists are in a sense “brands.” Many of them appear to promote or acquaint au- diences with their lifestyles through the music they create. Popular songs can serve not only as a mechanism for the subtle marketing of commer- cial consumer products, but also as a platform for marketing artists. Three types of branding devices are typically employed by songwriters: the men- tion of specific product brands, geographical places including cities and states, and well-known people (e.g., celebrities, cultural icons, and politi- cians). The aim of this study is to identify just how often these three types of lyrical references have occurred in popular songs through the years. How frequently have popular songs employed lyrics that may be serving the purpose of branding or advertising consumer products or the artists themselves, and are there observable trends regarding the practice over -

How Female Musicians Are Treated Differently in Music

University of Central Florida STARS Electronic Theses and Dissertations, 2004-2019 2006 10x The Talent = 1/3 Of The Credit: How Female Musicians Are Treated Differently In Music Meggan Jordan University of Central Florida Part of the Sociology Commons Find similar works at: https://stars.library.ucf.edu/etd University of Central Florida Libraries http://library.ucf.edu This Masters Thesis (Open Access) is brought to you for free and open access by STARS. It has been accepted for inclusion in Electronic Theses and Dissertations, 2004-2019 by an authorized administrator of STARS. For more information, please contact [email protected]. STARS Citation Jordan, Meggan, "10x The Talent = 1/3 Of The Credit: How Female Musicians Are Treated Differently In Music" (2006). Electronic Theses and Dissertations, 2004-2019. 946. https://stars.library.ucf.edu/etd/946 10X THE TALENT = 1/3 OF THE CREDIT HOW FEMALE MUSICIANS ARE TREATED DIFFERENTLY IN MUSIC by MEGGAN M. JORDAN B.A. University of Central Florida, 2004 A thesis submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts in the Department of Sociology in the College of Sciences at the University of Central Florida Orlando, Florida Summer Term 2006 © 2006 Meggan M. Jordan ii ABSTRACT This is an exploratory, qualitative study of female musicians and their experiences with discrimination in the music industry. Using semi-structured interviews, I analyze the experiences of nine women, ages 21 to 56, who are working as professional musicians, or who have worked professionally in the past. I ask them how they are treated differently based on their gender. -

A Woman's Place in Jazz in the 21St Century Valerie T

University of South Florida Scholar Commons Graduate Theses and Dissertations Graduate School June 2018 A Woman's Place in Jazz in the 21st Century Valerie T. Simuro University of South Florida, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarcommons.usf.edu/etd Part of the Feminist, Gender, and Sexuality Studies Commons, and the Philosophy Commons Scholar Commons Citation Simuro, Valerie T., "A Woman's Place in Jazz in the 21st Century" (2018). Graduate Theses and Dissertations. https://scholarcommons.usf.edu/etd/7363 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Graduate School at Scholar Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in Graduate Theses and Dissertations by an authorized administrator of Scholar Commons. For more information, please contact [email protected]. A Woman’s Place in Jazz in the 21st Century by Valerie T. Simuro A thesis is submitted in partial fulfillment of the Master of Arts, in Liberal Arts, in Humanities Concentration Department of Humanities and Cultural Studies at the University of South Florida Major Professor: Andrew Berish, Ph.D. Brook Sadler, Ph.D. Maria Cizmic, Ph.D. Date of Approval: June 21, 2018 Keywords: Esperanza Spalding, Gender, Race, Jazz, Age Copyright © 2018, Valerie T. Simuro ACKNOWLEDGMENT I would like to take this opportunity to express my deepest gratitude to, Dr. Brook Sadler who was instrumental in my acceptance to the Graduate Master’s Program at the University of South Florida. She is a brilliant teacher and a remarkable writer who guided and encouraged me throughout my years in the program. -

Title "Stand by Your Man/There Ain't No Future In

TITLE "STAND BY YOUR MAN/THERE AIN'T NO FUTURE IN THIS" THREE DECADES OF ROMANCE IN COUNTRY MUSIC by S. DIANE WILLIAMS Presented to the American Culture Faculty at the University of Michigan-Flint in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the Master of Liberal Studies in American Culture Date 98 8AUGUST 15 988AUGUST Firs t Reader Second Reader "STAND BY YOUR MAN/THERE AIN'T NO FUTURE IN THIS" THREE DECADES OF ROMANCE IN COUNTRY MUSIC S. DIANE WILLIAMS AUGUST 15, 19SB TABLE OF CONTENTS Preface Introduction - "You Never Called Me By My Name" Page 1 Chapter 1 — "Would Jesus Wear A Rolen" Page 13 Chapter 2 - "You Ain’t Woman Enough To Take My Man./ Stand By Your Man"; Lorrtta Lynn and Tammy Wynette Page 38 Chapter 3 - "Think About Love/Happy Birthday Dear Heartache"; Dolly Parton and Barbara Mandrell Page 53 Chapter 4 - "Do Me With Love/Love Will Find Its Way To You"; Janie Frickie and Reba McEntire F'aqe 70 Chapter 5 - "Hello, Dari in"; Conpempory Male Vocalists Page 90 Conclusion - "If 017 Hank Could Only See Us Now" Page 117 Appendix A - Comparison Of Billboard Chart F'osi t i ons Appendix B - Country Music Industry Awards Appendix C - Index of Songs Works Consulted PREFACE I grew up just outside of Flint, Michigan, not a place generally considered the huh of country music activity. One of the many misconception about country music is that its audience is strictly southern and rural; my northern urban working class family listened exclusively to country music. As a teenager I was was more interested in Motown than Nashville, but by the time I reached my early thirties I had became a serious country music fan. -

Dan Blaze's Karaoke Song List

Dan Blaze's Karaoke Song List - By Artist 112 Peaches And Cream 411 Dumb 411 On My Knees 411 Teardrops 911 A Little Bit More 911 All I Want Is You 911 How Do You Want Me To Love You 911 More Than A Woman 911 Party People (Friday Night) 911 Private Number 911 The Journey 10 cc Donna 10 cc I'm Mandy 10 cc I'm Not In Love 10 cc The Things We Do For Love 10 cc Wall St Shuffle 10 cc Dreadlock Holiday 10000 Maniacs These Are The Days 1910 Fruitgum Co Simon Says 1999 Man United Squad Lift It High 2 Evisa Oh La La La 2 Pac California Love 2 Pac & Elton John Ghetto Gospel 2 Unlimited No Limits 2 Unlimited No Limits 20 Fingers Short Dick Man 21st Century Girls 21st Century Girls 3 Doors Down Kryptonite 3 Oh 3 feat Katy Perry Starstrukk 3 Oh 3 Feat Kesha My First Kiss 3 S L Take It Easy 30 Seconds To Mars The Kill 38 Special Hold On Loosely 3t Anything 3t With Michael Jackson Why 4 Non Blondes What's Up 4 Non Blondes What's Up 5 Seconds Of Summer Don't Stop 5 Seconds Of Summer Good Girls 5 Seconds Of Summer She Looks So Perfect 5 Star Rain Or Shine Updated 08.04.2015 www.blazediscos.com - www.facebook.com/djdanblaze Dan Blaze's Karaoke Song List - By Artist 50 Cent 21 Questions 50 Cent Candy Shop 50 Cent In Da Club 50 Cent Just A Lil Bit 50 Cent Feat Neyo Baby By Me 50 Cent Featt Justin Timberlake & Timbaland Ayo Technology 5ive & Queen We Will Rock You 5th Dimension Aquarius Let The Sunshine 5th Dimension Stoned Soul Picnic 5th Dimension Up Up and Away 5th Dimension Wedding Bell Blues 98 Degrees Because Of You 98 Degrees I Do 98 Degrees The Hardest -

Leisure's Legacy

LEISURE STUDIES IN A GLOBAL Leisure’s ERA Legacy Challenging the Common Sense View of Free Time ROBERT A. STEBBINS Leisure Studies in a Global Era Series Editors Karl Spracklen Leeds Beckett University Leeds, United Kingdom Karen Fox University of Alberta Edmonton, Canada In this book series, we defend leisure as a meaningful, theoretical, fram- ing concept; and critical studies of leisure as a worthwhile intellectual and pedagogical activity. This is what makes this book series distinctive: we want to enhance the discipline of leisure studies and open it up to a richer range of ideas; and, conversely, we want sociology, cultural geog- raphies and other social sciences and humanities to open up to engaging with critical and rigorous arguments from leisure studies. Getting beyond concerns about the grand project of leisure, we will use the series to dem- onstrate that leisure theory is central to understanding wider debates about identity, postmodernity and globalisation in contemporary societ- ies across the world. The series combines the search for local, qualitatively rich accounts of everyday leisure with the international reach of debates in politics, leisure and social and cultural theory. In doing this, we will show that critical studies of leisure can and should continue to play a central role in understanding society. The scope will be global, striving to be truly international and truly diverse in the range of authors and topics. Editorial Board John Connell, Professor of Geography, University of Sydney, USA Yoshitaka Mori, Associate Professor, Tokyo University of the Arts, Japan Smitha Radhakrishnan, Assistant Professor, Wellesley College, USA Diane M. -

112 It's Over Now 112 Only You 311 All Mixed up 311 Down

112 It's Over Now 112 Only You 311 All Mixed Up 311 Down 702 Where My Girls At 911 How Do You Want Me To Love You 911 Little Bit More, A 911 More Than A Woman 911 Party People (Friday Night) 911 Private Number 10,000 Maniacs More Than This 10,000 Maniacs These Are The Days 10CC Donna 10CC Dreadlock Holiday 10CC I'm Mandy 10CC I'm Not In Love 10CC Rubber Bullets 10CC Things We Do For Love, The 10CC Wall Street Shuffle 112 & Ludacris Hot & Wet 1910 Fruitgum Co. Simon Says 2 Evisa Oh La La La 2 Pac California Love 2 Pac Thugz Mansion 2 Unlimited No Limits 20 Fingers Short Dick Man 21st Century Girls 21st Century Girls 3 Doors Down Duck & Run 3 Doors Down Here Without You 3 Doors Down Its not my time 3 Doors Down Kryptonite 3 Doors Down Loser 3 Doors Down Road I'm On, The 3 Doors Down When I'm Gone 38 Special If I'd Been The One 38 Special Second Chance 3LW I Do (Wanna Get Close To You) 3LW No More 3LW No More (Baby I'm A Do Right) 3LW Playas Gon' Play 3rd Strike Redemption 3SL Take It Easy 3T Anything 3T Tease Me 3T & Michael Jackson Why 4 Non Blondes What's Up 5 Stairsteps Ooh Child 50 Cent Disco Inferno 50 Cent If I Can't 50 Cent In Da Club 50 Cent In Da Club 50 Cent P.I.M.P. (Radio Version) 50 Cent Wanksta 50 Cent & Eminem Patiently Waiting 50 Cent & Nate Dogg 21 Questions 5th Dimension Aquarius_Let the sunshine inB 5th Dimension One less Bell to answer 5th Dimension Stoned Soul Picnic 5th Dimension Up Up & Away 5th Dimension Wedding Blue Bells 5th Dimension, The Last Night I Didn't Get To Sleep At All 69 Boys Tootsie Roll 8 Stops 7 Question -

Metaphoric and Metonymic Complexes in Phrasal Verb Interpretation Francisco José Ruiz De Mendoza Ibáñez and Alicia Galera-Masegosa 1-29

Language Value December 2011, Volume 3, Number 1 http://www.e-revistes.uji.es/languagevalue Copyright © 2011, ISSN 1989-7103 Table of Contents From the editors Antonio José Silvestre López, Mari Carmen Campoy Cubillo, and Miguel F. Ruiz Garrido i-vi Articles Going beyond metaphtonymy: Metaphoric and metonymic complexes in phrasal verb interpretation Francisco José Ruiz de Mendoza Ibáñez and Alicia Galera-Masegosa 1-29 Towards an integrated model of metaphorical linguistic expressions in English Ariadna Strugielska 30-48 Topological vs. lexical determination in English particle verbs (PVs) Renata Geld 49-75 Strategic construal of in and out in English particle verbs (PVs) Renata Geld and Ricardo Maldonado 76-113 Lexical decomposition of English prepositions and their fusion with verb lexical classes in motion constructions Ignasi Navarro i Ferrando 114-137 Analyses of the semantic features of the lexical bundle [(VERB) PREPOSITION the NOUN of] Siaw-Fong Chung, F.Y. August Chao, Tien-Yu Lan, and Yen-Yu Lin 138-152 Book and Multimedia Reviews Michael Rundell. Macmillan Collocations Dictionary for Learners of English Pedro A. Fuertes-Olivera 153-161 Terminology Management Systems for the development of (specialised) dictionaries: a focus on WordSmith Tools and Termstar XV Nuria Edo Marzá 162-173 Copyright © 2011 Language Value, ISSN 1989-7103. Articles are copyrighted by their respective authors Language Value December 2011, Volume 3, Number 1 pp. i-vi http://www.e-revistes.uji.es/languagevalue Copyright © 2011, ISSN 1989-7103 In Memoriam The journal editors and the Department of English Studies at the Universitat Jaume I wish to pay tribute to our colleague, friend and teacher, Dr. -

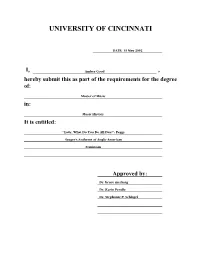

University of Cincinnati

UNIVERSITY OF CINCINNATI DATE: 13 May 2002 I, Amber Good , hereby submit this as part of the requirements for the degree of: Master of Music in: Music History It is entitled: ``Lady, What Do You Do All Day?'': Peggy Seeger's Anthems of Anglo-American Feminism Approved by: Dr. bruce mcclung Dr. Karin Pendle Dr. Stephanie P. Schlagel 1 “LADY, WHAT DO YOU DO ALL DAY?”: PEGGY SEEGER’S ANTHEMS OF ANGLO-AMERICAN FEMINISM A thesis submitted to the Division of Research and Advanced Studies of the University of Cincinnati in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of MASTER OF MUSIC in the Division of Composition, Musicology, and Theory of the College-Conservatory of Music 2002 by Amber Good B.M. Vanderbilt University, 1997 Committee Chair: Dr. bruce d. mcclung 2 ABSTRACT Peggy Seeger’s family lineage is indeed impressive: daughter of composers and scholars Charles and Ruth Crawford Seeger, sister of folk icons Mike and Pete Seeger, and widow of British folksinger and playwright Ewan MacColl. Although this intensely musical genealogy inspired and affirmed Seeger’s professional life, it has also tended to obscure her own remarkable achievements. The goal of the first part of this study is to explore Peggy Seeger’s own history, including but not limited to her life within America’s first family of folk music. Seeger’s story is distinct from that of her family and even from that of most folksingers in her generation. The second part of the thesis concerns Seeger’s contributions to feminism through her songwriting, studies, and activism. -

Practical Lessons and Resources for Teachers from Foundation to Year 10

Practical lessons and resources for teachers from Foundation to Year 10 Fostering Volunteering and the a culture Australian of giving Curriculum A National Innovation and Collaboration Project Volunteering ACT is proudly managed by Volunteering and Contact ACT. Volunteering and Contact ACT is funded by the Department of Social Services to implement the Fostering a Culture of Giving: Volunteering and the Australian Curriculum, a National Innovation and Collaboration project. August 2015 FOSTERING A CULTURE OF GIVING: VOLUNTEERING AND THE AUSTRALIAN CURRICULUM FOREWORD As our country’s peak body for volunteering, Volunteering Australia’s mission is to lead, strengthen, promote and celebrate volunteering. We encourage and support positive civic participation through volunteer service by people of all ages and from all walks of life. A key enabler in achieving our mission is the development of innovative, practical and accessible resources. We are extremely pleased therefore to welcome the publication of a new nationally significant resource, Volunteering and the Australian Curriculum – Fostering a Culture of Giving: Practical Lessons for Teachers from Foundation to Year 10. This resource was developed as one of a number of National Innovation and Collaboration Projects funded by the Federal Department of Social Services under its Families and Communities Program. Australia’s strong tradition of volunteering must continue to be promoted and strengthened in an ever-changing world. Opening up opportunities in the mainstream school setting for all young Australians to learn about volunteering and to embrace a culture of giving has the potential to set patterns for lifetime fulfilment, community connection and better health. There is strong research evidence that students’ active civic involvement supports their educational participation and achievement. -

Journal of Hip Hop Studies

et al.: Journal of Hip Hop Studies Published by VCU Scholars Compass, 2014 1 Journal of Hip Hop Studies, Vol. 1 [2014], Iss. 1, Art. 1 Editor in Chief: Daniel White Hodge, North Park University Book Review Editor: Gabriel B. Tait, Arkansas State University Associate Editors: Cassandra Chaney, Louisiana State University Jeffrey L. Coleman, St. Mary’s College of Maryland Monica Miller, Lehigh University Editorial Board: Dr. Rachelle Ankney, North Park University Dr. Jason J. Campbell, Nova Southeastern University Dr. Jim Dekker, Cornerstone University Ms. Martha Diaz, New York University Mr. Earle Fisher, Rhodes College/Abyssinian Baptist Church, United States Dr. Daymond Glenn, Warner Pacific College Dr. Deshonna Collier-Goubil, Biola University Dr. Kamasi Hill, Interdenominational Theological Center Dr. Andre Johnson, Memphis Theological Seminary Dr. David Leonard, Washington State University Dr. Terry Lindsay, North Park University Ms. Velda Love, North Park University Dr. Anthony J. Nocella II, Hamline University Dr. Priya Parmar, SUNY Brooklyn, New York Dr. Soong-Chan Rah, North Park University Dr. Rupert Simms, North Park University Dr. Darron Smith, University of Tennessee Health Science Center Dr. Jules Thompson, University Minnesota, Twin Cities Dr. Mary Trujillo, North Park University Dr. Edgar Tyson, Fordham University Dr. Ebony A. Utley, California State University Long Beach, United States Dr. Don C. Sawyer III, Quinnipiac University Media & Print Manager: Travis Harris https://scholarscompass.vcu.edu/jhhs/vol1/iss1/1 2 et al.: Journal of Hip Hop Studies Sponsored By: North Park Universities Center for Youth Ministry Studies (http://www.northpark.edu/Centers/Center-for-Youth-Ministry-Studies) . FO I ITH M I ,I T R T IDIE .ORT ~ PAru<.UN~V RSllY Save The Kids Foundation (http://savethekidsgroup.org/) 511<, a f't.dly volunteer 3raSS-roots or3an:za6on rooted :n h;,P ho,P and transf'orMat:ve j us6c.e, advocates f'or alternat:ves to, and the end d, the :nc..arc.eration of' al I youth .