Trial by Jewry: the Jewish Figure As Subversive Critic in the Plays of The

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

'Otherness' in Shakespeare's Othello and the Merchant Of

The Representation of ‘Otherness’ in Shakespeare’s Othello and The Merchant of Venice Othello and Shylock Diplomarbeit zur Erlangung des akademischen Grades einer Magistra der Philosophie an der Karl-Franzens-Universität Graz vorgelegt von Gerda TISCHLER am Institut für Anglistik Begutachter: o. Univ.-Prof. Mag. Dr. Werner Wolf Graz, 2013 Acknowledgement First and foremost, I would like to express my gratitude to my supervisor Professor Werner Wolf, who has not only offered valuable guidance, assistance, and help in the composition of this thesis, but who has also been an inspiring and very encouraging mentor throughout the rest of my studies, supporting me in many ways. Additionally, I would like to thank my former teachers Waltraud Wagner and Liselotte Schedlbauer, who stirred up my enthusiasm for both the English language and literature. I also want to express my warmest and sincere thanks to my parents, who have always encouraged me in the actualisation of my dreams and who have been incredibly supportive in any respect throughout my entire life. Besides, I want to thank Christopher for showing so much sympathy and understanding, and for making me laugh wholeheartedly at least once a day. Lastly, I am indebted to my family, friends, and anyone without whom the completion of this thesis would not have been possible. Contents 1 Introduction ............................................................................................................... 5 2 The ‘Other’ – Attempts at an Explanation ............................................................ -

NP 2013.Docx

LISTE INTERNATIONALE DES NOMS PROTÉGÉS (également disponible sur notre Site Internet : www.IFHAonline.org) INTERNATIONAL LIST OF PROTECTED NAMES (also available on our Web site : www.IFHAonline.org) Fédération Internationale des Autorités Hippiques de Courses au Galop International Federation of Horseracing Authorities 15/04/13 46 place Abel Gance, 92100 Boulogne, France Tel : + 33 1 49 10 20 15 ; Fax : + 33 1 47 61 93 32 E-mail : [email protected] Internet : www.IFHAonline.org La liste des Noms Protégés comprend les noms : The list of Protected Names includes the names of : F Avant 1996, des chevaux qui ont une renommée F Prior 1996, the horses who are internationally internationale, soit comme principaux renowned, either as main stallions and reproducteurs ou comme champions en courses broodmares or as champions in racing (flat or (en plat et en obstacles), jump) F de 1996 à 2004, des gagnants des neuf grandes F from 1996 to 2004, the winners of the nine épreuves internationales suivantes : following international races : Gran Premio Carlos Pellegrini, Grande Premio Brazil (Amérique du Sud/South America) Japan Cup, Melbourne Cup (Asie/Asia) Prix de l’Arc de Triomphe, King George VI and Queen Elizabeth Stakes, Queen Elizabeth II Stakes (Europe/Europa) Breeders’ Cup Classic, Breeders’ Cup Turf (Amérique du Nord/North America) F à partir de 2005, des gagnants des onze grandes F since 2005, the winners of the eleven famous épreuves internationales suivantes : following international races : Gran Premio Carlos Pellegrini, Grande Premio Brazil (Amérique du Sud/South America) Cox Plate (2005), Melbourne Cup (à partir de 2006 / from 2006 onwards), Dubai World Cup, Hong Kong Cup, Japan Cup (Asie/Asia) Prix de l’Arc de Triomphe, King George VI and Queen Elizabeth Stakes, Irish Champion (Europe/Europa) Breeders’ Cup Classic, Breeders’ Cup Turf (Amérique du Nord/North America) F des principaux reproducteurs, inscrits à la F the main stallions and broodmares, registered demande du Comité International des Stud on request of the International Stud Book Books. -

Film Club Sky 328 Newsletter Freesat 306 MAY/JUNE 2020 Virgin 445

Freeview 81 Film Club Sky 328 newsletter Freesat 306 MAY/JUNE 2020 Virgin 445 Dear Supporters of Film and TV History, Hoping as usual that you are all safe and well in these troubled times. Our cinema doors are still well and truly open, I’m pleased to say, the channel has been transmitting 24 hours a day 7 days a week on air with a number of premières for you all and orders have been posted out to you all every day as normal. It’s looking like a difficult few months ahead with lack of advertising on the channel, as you all know it’s the adverts that help us pay for the channel to be transmitted to you all for free and without them it’s very difficult. But we are confident we can get over the next few months. All we ask is that you keep on spreading the word about the channel in any way you can. Our audiences are strong with 4 million viewers per week , but it’s spreading the word that’s going to help us get over this. Can you believe it Talking Pictures TV is FIVE Years Old later this month?! There’s some very interesting selections in this months newsletter. Firstly, a terrific deal on The Humphrey Jennings Collections – one of Britain’s greatest filmmakers. I know lots of you have enjoyed the shorts from the Imperial War Museum archive that we have brought to Talking Pictures and a selection of these can be found on these DVD collections. -

TO CONSIGNORS Hip Color Year No

INDEX TO CONSIGNORS Hip Color Year No. Name Sex Foaled Sire Dam ALL DREAMS EQUINE, AGENT Barn 2 Two-Year-Olds 16 ................................. ......b. c................2011 Dunkirk .......................Meadow Melody 212 ................................. ......dk. b./br. c. ...2011 With Distinction ..........Star Julia 285 ................................. ......b. f. ................2011 Grand Slam................Val's Jazz 418 ................................. ......ch. f. ..............2011 Kitten's Joy.................Cheering Dreams ALL IN LINE STABLES, AGENT II Barn 3 Two-Year-Old 180 ................................. ......b. c................2011 Smart Strike................Silk Road ALL IN LINE STABLES, AGENT III Barn 3 Two-Year-Old 453 ................................. ......ch. c. .............2011 English Channel.........Cyrillic ALL IN SALES (TONY BOWLING), AGENT Barn 10 Two-Year-Olds 25 ................................. ......ch. c. .............2011 Tiz Wonderful .............Mira Costa 136 ................................. ......b. c................2011 El Corredor.................River Cache 224 ................................. ......gr/ro. c...........2011 Dunkirk .......................Storm Fleet 235 ................................. ......ch. c. .............2011 Talent Search .............Summus 349 ................................. ......dk. b./br. c. ...2011 With Distinction ..........Always On the Go 426 ................................. ......b. c................2011 Lion Tamer..................Cinefila -

The 13Th Annual ISNA-CISNA Education Forum Welcomes You!

13th Annual ISNA Education Forum April 6th -8th, 2011 The 13th Annual ISNA-CISNA Education Forum Welcomes You! The ISNA-CISNA Education Forum, which has fostered professional growth and development and provided support to many Islamic schools, is celebrating its 13-year milestone this April. We have seen accredited schools sprout from grassroots efforts across North America; and we credit Allah, subhanna wa ta‘alla, for empowering the many men and women who have made the dreams for our schools a reality. Today the United States is home to over one thousand weekend Islamic schools and several hundred full-time Islamic schools. Having survived the initial challenge of galvanizing community support to form a school, Islamic schools are now attempting to find the most effective means to build curriculum and programs that will strengthen the Islamic faith and academic excellence of their students. These schools continue to build quality on every level to enable their students to succeed in a competitive and increasingly multicultural and interdependent world. The ISNA Education Forum has striven to be a major platform for this critical endeavor from its inception. The Annual Education Forum has been influential in supporting Islamic schools and Muslim communities to carry out various activities such as developing weekend schools; refining Qur‘anic/Arabic/Islamic Studies instruction; attaining accreditation; improving board structures and policies; and implementing training programs for principals, administrators, and teachers. Thus, the significance of the forum lies in uniting our community in working towards a common goal for our youth. Specific Goals 1. Provide sessions based on attendees‘ needs, determined by surveys. -

Reply to the Prosecutors' Legal and Factual Claims

STATE OF NEW YORK – COURT OF APPEALS -------------------------------------------------------------------x PEOPLE OF THE STATE OF NEW YORK, ) -against- ) APL-2013-00064 RAPHAEL GOLB, ) Appellant. ) --------------------------------------------------------------------x REPLY BRIEF OF DEFENDANT-APPELLANT RONALD L. KUBY LEAH M. BUSBY Law Office of Ronald L. Kuby 119 West 23rd St., Suite 900 New York, New York 10011 (212) 529-0223 (212) 529-0644 (facsimile) For Appellant Raphael Golb Dated: New York, New York January 24, 2014 TABLE OF CONTENTS Table of Cases and Authorities ................................................................................. ii REPLY TO RESPONDENT’S COUNTERSTATEMENT OF FACTS .................... 1 ARGUMENT .......................................................................................................... 12 I. WHEN LITERALLY ANYTHING CAN BE A LEGALLY COGNIZABLE BENEFIT OR HARM, RESPONDENT CAN CRIMINALIZE ANYONE FOR WRITING UNDER THE NAME OF ANOTHER....................................................................... 12 A. RESPONDENT ERRONEOUSLY ASSERTS THAT ANY FORM OF DISCOMFORT IS AN INJURY AND ANY FORM OF GRATIFICATION IS A BENEFIT ............. 12 B. RESPONDENT ARTICULATES NO LIMITING PRINCIPLE EXCEPT ITS OWN DISCRETION. ................... 16 C. RESPONDENT MISREADS ALVAREZ ................................. 21 D. THE TRIAL COURT DIRECTED THE JURY TO NOT CONSIDER GOLB’S FIRST AMENDMENT RIGHTS OR ISSUES OF FREEDOM OF SPEECH. ............................. 23 II. THE COMMUNICATIONS THAT ARE THE SUBJECT -

Black, J. (1991). Whatever Happened to Baby Logic? Proceedings of the Second International Conference on Argumentation

This paper was originally published as: Black, J. (1991). Whatever happened to baby logic? Proceedings of the Second International Conference on Argumentation. Amsterdam: International Society for the Study of Argumentation. Whatever Happened to Baby Logic? John Black * Originally published in Proceedings of the Second International Conference on Argumentation, Amsterdam, Stichting Internationaal Centrum voor de Studie van Argumentatie en Taalbeheersing, 1991. A. The Retreat of Baby Logic The title of this essay looks forward to a time when teachers of critical thinking, engaged in pedagogical rumination over their morning cups of tea, may ask themselves why elementary formal logic is no longer included in the content of their courses. In many parts of North America, this scenario is already enacted. Formal approaches to critical thinking, however, still hold sway in isolated pockets of the philosophical academic community. This polemic is directed primarily at those pockets, though it may be of interest to those who have already made the leap to informal logic and beyond, but are interested in exploring the pedagogical motivations for this leap. "Baby logic" is the somewhat deprecatory name given by philosophers to the courses they teach in introductory formal logic. Though these often contain an informal component, they typically focus on the propositional calculus and first-order predicate calculus. Standard content would be translations of English sentences into symbolism, differences between the logical connectives and their English colleagues (including the paradoxes of material implication), the notion of an axiomatic system, axioms and theorems, derivations (often by a natural deduction system), and such semantic tools as truth-tables and truth-trees. -

Restorative Justice: a Marxist Analysis

Restorative Justice: A Marxist Analysis Raymond Anthony Koen Thesis Presented for the Degree of DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY in the Institute of Criminology Faculty of Law UNIVERSITY OF CAPE TOWN August 2005 Supervisor: Professor Dirk van Zyl Smit The copyright of this thesis vests in the author. No quotation from it or information derived from it is to be published without full acknowledgementTown of the source. The thesis is to be used for private study or non- commercial research purposes only. Cape Published by the University ofof Cape Town (UCT) in terms of the non-exclusive license granted to UCT by the author. University ABSTRACT Restorative Justice: A Marxist Analysis RAKoen Abstract Restorative justice is the enfant terrible of the criminological world. In no time, it has rocked the edifice of the criminal justice system, challenging the latter's very existence. It has inculpated the retributive focus of criminal justice in the creation and reproduction of the contemporary crisis of criminality. It has proclaimed itself to be in possession of the solution to that crisis. And it has offered itself as the path to a higher plane of human existence characterized by respect, trust, mutuality, and the like. The restorationist answer to the crisis of criminality is a radical one. Taking their theoretical lead from Nils Christie, the adherents of restorative justice propose the privatization of the criminal episode. That is, they contend that crime should be removed from the public arena and reconstituted as a private conflict in which victim, offender and community all have an interest as 'stakeholders'. The crime should be comprehended as the property of these 'stakeholders' who may dispose of it according to terms and conditions which they negotiate inter se, without reference to a public authority. -

AQHA Points in Open, Amateur, Youth & Novice Classes, from Sale Date Through August 31

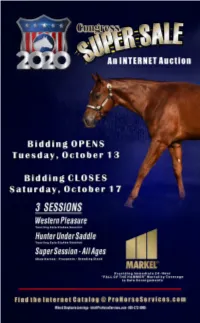

Stoney’s Web Design Web Stoney’s Our passion is protecting yours. Allocate Your Assets VS Code Blue Owned by Gerard W. and Katherine K. Tobin Frank Costantini 800-314-0077 Debbie Kail 209-601-7175 (Director, Western Disciplines) Ryan Kail 480-294-3615 David Buffamoyer 877-684-6773 Chloe Lawrence 682-229-0876 Susan Costantini 800-314-0077 Diane Paris 909-938-3008 April Devitt 541-840-9687 Karen Shedlauskas 330-565-0762 Tammy Hill 607-725-3939 Robb Walther 503-703-0414 Andreini and Company, a partnered agency Courtney Clagg 704-860-5361 Johne Dobbs 217-254-5261 For European inquiries, email Jeff Tebow 405-820-9997 Muriel de Moubray at Vicki Tebow 405-245-6716 [email protected] markelwestern.com /MarkelHorse Products and services are offered through Markel Specialty, a business division of Markel Service Incorporated (national producer number 27585). Policies are written by one or more Markel insurance companies. Terms and conditions for rate and coverage may vary. Markel® is a registered trademark of the Markel Corporation. Bidding Opens at 10 a.m. Tuesday, October 13, 2020 Saturday, OCTOBER 17, 2020 Bidding starts Closing at 12:00 noon ET 3 Sessions Western Pleasure Yearling Stakes Session - Hip No 101 to 159 Hunter Under Saddle Yearling Stakes Session - Hip No 201 to 216 Super Session - All Ages - Hip No 301 to 331 Late entries will appear in the internet catalog only - and will sell within their session after the horses in this catalog. Scan HERE Bid Closing is STAGGERED - to view internet catalog. closing 3 minutes apart. -

The Role of Reasoning in Constructing a Persuasive Argument

The Role of Reasoning in Constructing a Persuasive Argument <http://www.orsinger.com/PDFFiles/constructing-a-persuasive-argument.pdf> [The pdf version of this document is web-enabled with linking endnotes] Richard R. Orsinger [email protected] http://www.orsinger.com McCurley, Orsinger, McCurley, Nelson & Downing, L.L.P. San Antonio Office: 1717 Tower Life Building San Antonio, Texas 78205 (210) 225-5567 http://www.orsinger.com and Dallas Office: 5950 Sherry Lane, Suite 800 Dallas, Texas 75225 (214) 273-2400 http://www.momnd.com State Bar of Texas 37th ANNUAL ADVANCED FAMILY LAW COURSE August 1-4, 2011 San Antonio CHAPTER 11 © 2011 Richard R. Orsinger All Rights Reserved The Role of Reasoning in Constructing a Persuasive Argument Chapter 11 Table of Contents I. THE IMPORTANCE OF PERSUASION.. 1 II. PERSUASION IN ARGUMENTATION.. 1 III. BACKGROUND.. 2 IV. USER’S GUIDE FOR THIS ARTICLE.. 2 V. ARISTOTLE’S THREE COMPONENTS OF A PERSUASIVE SPEECH.. 3 A. ETHOS.. 3 B. PATHOS.. 4 C. LOGOS.. 4 1. Syllogism.. 4 2. Implication.. 4 3. Enthymeme.. 4 (a) Advantages and Disadvantages of Commonplaces... 5 (b) Selection of Commonplaces.. 5 VI. ARGUMENT MODELS (OVERVIEW)... 5 A. LOGIC-BASED ARGUMENTS. 5 1. Deductive Logic.. 5 2. Inductive Logic.. 6 3. Reasoning by Analogy.. 7 B. DEFEASIBLE ARGUMENTS... 7 C. THE TOULMIN ARGUMENTATION MODEL... 7 D. FALLACIOUS ARGUMENTS.. 8 E. ARGUMENTATION SCHEMES.. 8 VII. LOGICAL REASONING (DETAILED ANALYSIS).. 8 A. DEDUCTIVE REASONING.. 8 1. The Categorical Syllogism... 8 a. Graphically Depicting the Simple Categorical Syllogism... 9 b. A Legal Dispute as a Simple Syllogism.. 9 c. -

Lecture the KING JAMES BIBLE 1611

1 The King James Bible 1611 Professor Bill Gibson William Gibson is Professor of Ecclesiastical History and Director of the Oxford Centre for Methodism and Church History at Oxford Brookes University. He is a specialist in the church history of England in the seventeenth and eighteenth centuries and has written on church and state in this period. His most recent books have been Britain 1660- 1851: The Making of the Nation, Constable Robinson, 2011 and James II and the Trial of the Seven Bishops, Palgrave Macmillan, 2009. He is currently editing the Oxford Handbook of the Modern British Sermon 1689- 1901 for Oxford University Press." Abstract: This brief article is the text of a lecture delivered at the annual Kingdom Lecture series for the Parishes of St Martins and All Saints, Ealing Common, London in November 2011. As such it is not intended as a work of research, rather an attempt to offer some more accessible aspects of the antecedents, creation and afterlife of the King James Version of the Bible. The lecture considers the range of translations of the Bible before 1611, the reasons why a Bible was needed in 1611, the process of constructing the King James Version of the Bible, and the afterlife of the King James Bible and especially its language. 2 TRANSLATIONS OF THE BIBLE BEFORE 1611 There were a number of versions of the Bible in English well before 1611. In fact as early as the Anglo-Saxon period there were some translations of individual books into Anglo-Saxon, and King Alfred seems to have advocated translation of the Bible into Anglo-Saxon. -

92. Judaism and Jews B R E T T D

book identifi es Easter Term as starting the eighteenth day such an overt liturgical allusion as Shakespeare provides aft er Easter and ending the Monday aft er the Ascension. in the title Twelft h Night was certainly not a reference to Trinity Term began the Friday aft er Trinity Sunday and the religious nature of the feast, or even to a performance ended June 28. Michaelmas Term began October 9 or 10 date, but to the atmosphere of frivolous chaos that had and ended November 28 or 29. Hillary Term began January developed over the years. It is far more likely that the 23 or 24 and ended February 12 or 13. During term time, timing of these performances was based on ecclesiasti- the court did not sit on Sundays or on the feasts of the cal rules regarding secular entertainment during certain Ascension, John the Baptist, All Saints, or the Purifi cation seasons of the year. Th e penitential seasons of Advent of Mary. and Lent, for example, were inappropriate for theatrical amusements. Dramatic performances S o u r c e c i t e d and the liturgical year G a r d i n e r , S a m u e l . Th e Cognizance of a True Christian, or the Dramatic performances were oft en scheduled to coin- outward markes whereby he may be the better knowne , etc. cide with certain church seasons or feasts. Th is practice London : Th omas Creede , 1597 . was not new to the English Renaissance, however. Th e medieval mystery plays serve as a prime example of the F u r t h e r r e a d i n g long-standing connection between theater, religion, and B r y a n t , J a m e s C .