Program Book

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Fiery Pianist Khatia Buniatishvili Makes Indianapolis Symphony Orchestra Debut in Lilly Classical Series Concerts Jan

Date: Monday, January 16, 2012 Contact: Tim Northcutt – (317) 262-4904 Jessica Di Santo – (317) 229-7082 Fiery Pianist Khatia Buniatishvili Makes Indianapolis Symphony Orchestra Debut in Lilly Classical Series Concerts Jan. 26-28 at Clowes Memorial Hall 2008 Arthur Rubinstein Competition prize winner performs Rachmaninoff Second Piano Concerto INDIANAPOLIS – As one of the fast-rising young stars in classical music, pianist Khatia Buniatishvili will make her Indianapolis Symphony Orchestra debut in performances of Sergei Rachmaninoff’s passionate and colorful Second Piano Concerto to highlight Lilly Classical Series concerts Thursday through Saturday, January 26-28, at Clowes Memorial Hall, located at 4602 Sunset Avenue on the Butler University campus. Originally scheduled for the Hilbert Circle Theatre, the venue change was prompted by the needs of the National Football League and the Indianapolis Super Bowl XLVI Committee to reserve large venues in the downtown area that are capable of hosting various Super Bowl events and activities. Preparations to host NBC’s Live with Jimmy Fallon during Super Bowl week will be underway at the ISO’s home that weekend. This all-Russian classical weekend, conducted by Princeton Symphony Orchestra Music Director Rossen Milanov, will open with Dmitri Shostakovich’s Festive Overture, a light and celebratory piece that the composer wrote to mark the anniversary of the Bolshevik overthrow of the Russian government in 1917. Buniatishvili will introduce herself to Indianapolis audiences in performances of one of the crown jewels of the piano repertoire, Sergei Rachmaninoff’s popular Second Piano Concerto. This glittering and melodic work showcases the technical artistry of the soloist with many rhapsodic moments spotlighting the pianist. -

[email protected] N

FOR IMMEDIATE RELEASE UPDATED May 28, 2015 February 17, 2015 Contact: Katherine E. Johnson (212) 875-5718; [email protected] NEW YORK PHILHARMONIC TO RETURN TO BRAVO! VAIL FOR 13th-ANNUAL SUMMER RESIDENCY, JULY 24–31, 2015 Music Director Alan Gilbert To Lead Three Programs Bramwell Tovey and Joshua Weilerstein Also To Conduct Soloists To Include Violinist Midori, Cellist Alisa Weilerstein, Pianists Jon Kimura Parker and Anne-Marie McDermott, Acting Concertmaster Sheryl Staples, Principal Viola Cynthia Phelps, Soprano Julia Bullock, and Tenor Ben Bliss New York Philharmonic Musicians To Perform Chamber Concert The New York Philharmonic will return to Bravo! Vail in Colorado for the Orchestra’s 13th- annual summer residency there, featuring six concerts July 24–31, 2015, as well as a chamber music concert performed by Philharmonic musicians. Music Director Alan Gilbert will conduct three programs, July 29–31, including an all-American program and works by Mendelssohn, Mahler, Mozart, and Shostakovich. The other Philharmonic concerts, conducted by Bramwell Tovey (July 24 and 26) and former New York Philharmonic Assistant Conductor Joshua Weilerstein (July 25), will feature works by Grieg, Elgar, Tchaikovsky, Rachmaninoff, and Richard Strauss, among others. The soloists appearing during the Orchestra’s residency are pianists Jon Kimura Parker and Anne-Marie McDermott, cellist Alisa Weilerstein, violinist Midori, soprano Julia Bullock and tenor Ben Bliss, and Acting Concertmaster Sheryl Staples and Principal Viola Cynthia Phelps. The New York Philharmonic has performed at Bravo! Vail each summer since 2003. Alan Gilbert will lead the concert on Wednesday, July 29, featuring Mendelssohn’s Violin Concerto, with Midori as soloist, and Mahler’s Symphony No. -

SHEDDING LIGHT on BULGARIAN SYMPHONY ORCHESTRAS /PIANO Or FORTЕ

SHEDDING LIGHT ON BULGARIAN SYMPHONY ORCHESTRAS /PIANO or FORTЕ/ Brief historic notes Orchestral music-making in Bulgaria goes back to mid-nineteenth century when in the Northeastern, multilingual town of Shumen the first ensemble was founded. It had entertainment and promotional purposes rather than serious concert activities. The significance of the ensemble though is mainly in the first establishment of a repertoire (Bulgarian and foreign) which was suitable for performance, as well as bringing together professionally educated national musicians and music-makers. Over WW2 orchestras developed in Bulgaria in lows and peaks. Those days gave rise to the Guards Orchestra (1892) conducted by Joseph Hohola; the Academic Symphony Orchestra (1928) and the Royal Military Symphony Orchestra (1936)both founded in Sofia by Prof. Sasha Popov; the State Philharmonic Orchestra at the National Opera (1935). At concerts in Bulgaria and abroad they perform major works by national and international musical classics. These ensembles invited outstanding guest conductors and soloists – Fausto Magnani, Karl Bohm, Bruno Walter, Edmondo de Vecchi, Emil Kupper, Carlo Zecchi, Henry Marteau, Paul Wittgenstein, Dinu Lipatti etc. After the end of the war the dynamic history of Bulgarian orchestras included both the above listed and numerous new ensembles founded all over the country. The Sofia Philharmonic Orchestra continued the tradition of the Sofia-based ensembles. The Philharmonic has performed with conductors Konstantin Iliev, Dobrin Petkov, Vassil Stefanov, Vladi Simeonov, Dimitar Manolov, Yordan Dafov, Emil Tabakov etc. At approximately the same time the capital saw the rise and establishment of yet another outstanding ensemble – the Symphony Orchestra of the Bulgarian National Radio (1948). -

Ning Fengviolin Virtuosismo

CHANNEL CLASSICS CCS 40719 NING FENG VIOLIN PAGANINI&VIEUXTEMPS VIRTUOSISMO ORQUESTA SINFÓNICA DEL PRINCIPADO DE ASTURIAS ROSSEN MILANOV CONDUCTOR Ning Feng (photo: Lawrence Tsang) 2 NING FENG returns to the Shanghai Symphony Orchestra under the baton of Yu Long. “Ning Feng’s total mastery could be seen in the In recital and chamber music Ning Feng precision and sweep of his bow, and heard in the regularly performs with Igor Levit and Daniel effortless tonal range, from sweet to sumptuous.” Müller-Schott, amongst others, and in 2012 New Zealand Herald - founded the Dragon Quartet. He appears at major venues and festivals such as the Wigmore Hall in Ning Feng is recognised internationally as an artist London, the Concertgebouw Amsterdam, National of great lyricism, innate musicality and stunning Centre for Performing Arts (Beijing) as well as the virtuosity. Blessed with an impeccable technique Schubertiade, Mecklenburg-Vorpommern and Hong and a silken tone, his palette of colours ranges from Kong International Chamber Music Festivals. intimate delicacy to a ferocious intensity. The Berlin Born in Chengdu, China, Ning Feng studied at based Chinese violinist performs across the globe the Sichuan Conservatory of Music, the Hanns Eisler with major orchestras and conductors, in recital School of Music (Berlin) with Antje Weithaas and and chamber concerts. the Royal Academy of Music (London) with Hu Kun Recent successes have included a return to where he was the first student ever to be awarded the Budapest Festival Orchestra with Iván Fischer -

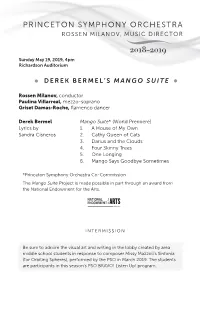

Mango Suite Program Pages

PRINCETON SYMPHONY ORCHESTRA ROSSEN MILANOV, MUSIC DIRECTOR 2018–2019 Sunday May 19, 2019, 4pm Richardson Auditorium DEREK BERMEL’S MANGO SUITE Rossen Milanov, conductor Paulina Villarreal, mezzo-soprano Griset Damas-Roche, flamenco dancer Derek Bermel Mango Suite* (World Premiere) Lyrics by 1. A House of My Own Sandra Cisneros 2. Cathy Queen of Cats 3. Darius and the Clouds 4. Four Skinny Trees 5. One Longing 6. Mango Says Goodbye Sometimes *Princeton Symphony Orchestra Co-Commission The Mango Suite Project is made possible in part through an award from the National Endowment for the Arts. INTERMISSION Be sure to admire the visual art and writing in the lobby created by area middle school students in response to composer Missy Mazzoli’s Sinfonia (for Orbiting Spheres), performed by the PSO in March 2019. The students are participants in this season’s PSO BRAVO! Listen Up! program. Manuel de Falla El amor brujo Introducción y escena (Introduction and Scene) En la cueva (In the Cave) Canción del amor dolido (Song of Love’s Sorrow) El Aparecido (The Apparition) Danza del terror (Dance of Terror) El círculo mágico (The Magic Circle) A medianoche (Midnight) Danza ritual del fuego (Ritual Fire Dance) Escena (Scene) Canción del fuego fatuo (Song of the Will-o’-the-Wisp) Pantomima (Pantomime) Danza del juego de amor (Dance of the Game of Love) Final (Finale) El sombrero de tres picos (The Three-Cornered Hat), Suite No. 1 Introduction—Afternoon Dance of the Miller’s Wife (Fandango) The Corregidor The Grapes La vida breve, Spanish Dance No. 1 This concert is made possible in part through the support of Yvonne Marcuse. -

GEORGIEV Martin

MARTIN GEORGIEV’s artistic activity connects the fields of composition, conducting and research in a symbiosis. As a composer and conductor he has collaborated with leading orchestras and ensembles, such as the Brussels Philharmonic, BBC Symphony Orchestra, Bulgarian National Radio Orchestra, Heidelberg Philharmonic Orchestra, Sofia National Philharmonic Orchestra, National Orchestra of Belgium, Azalea Ensemble, Manson Ensemble, Cosmic Voices choir, Isis Ensemble and Ensemble Musiques Nouvelles. More recently he was Composer in Residence to the City of Heidelberg - 'Komponist für Heidelberg 2012|13", featuring the orchestral commission The Secret which premiered in 2013 with the Heidelberg Philharmonic Orchestra conducted by the composer. Since 2013 he works as Assistant Conductor for the Royal Ballet at ROH Covent Garden, London, where he is involved with a number of world premieres. In 2010-11 he was SAM Embedded Composer with the BBC Symphony Orchestra, London. He has completed a PhD doctorate in Composition at the Royal Academy of Music, University of London (2012), in which he developed his Morphing Modality technique for composition. He also holds Masters' degrees in both Composition and Conducting from the Royal Academy of Music and the National Academy of Music 'Pancho Vladigerov', Sofia, Bulgaria. Born in 1983 at Varna, Bulgaria, he is based in London since 2005, holding both Bulgarian and British citizenship. He is a laureate of the International Composers' Forum TACTUS in Brussels, Belgium, where his works featured in the selection in 2004, 2008 and 2011; the Grand Prize for Symphonic Composition dedicated to the 75th Anniversary of the Sofia National Philharmonic Orchestra in 2003; the UBC Golden Stave Award in 2004; orchestral commission prize in memory of Sir Henry Wood by the Royal Academy of Music, London, in 2011; he was a finalist of the Hindemith Prize of the Schleswig-Holstein Music Festival in Germany in 2011 and a recipient of 15 prizes from national and international competitions as a percussionist. -

Edition 4 | 2019-2020

A Message from the Chair of the Board of Trustees 4 2020 Musician Roster 5 MARCH 6-7 11 Peaks of Beauty and Devotion MARCH 20-21 19 Beethoven at 250: An Apotheosis of Energy MARCH 27-28 27 The Rite of Spring APRIL 17-18 35 Beethoven at 250: The Ninth Symphony Spotlight on Education 50 Board of Trustees/Staff 51 Friends of the Columbus Symphony 53 Columbus Symphony League 54 Future Inspired 55 Partners in Excellence 57 Corporate and Foundation Partners 57 Individual Partners 58 In Kind 61 Tribute Gifts 61 Legacy Society 64 Concert Hall & Ticket Information 67 ADVERTISING Onstage Publications 937-424-0529 | 866-503-1966 e-mail: [email protected] www.onstagepublications.com The Columbus Symphony program is published in association with Onstage Publications, 1612 Prosser Avenue, Dayton, Ohio 45409. The Columbus Symphony program may not be reproduced in whole or in part without written permission from the publisher. Onstage Publications is a division of Just Business!, Inc. Contents © 2020. All rights reserved. Printed in the U.S.A. A MESSAGE FROM THE CHAIR OF THE BOARD OF TRUSTEES Dear Columbus Symphony Supporter, As our 2019–20 season comes to a close, we again thank you for your support of quality, live performances of orchestral music in our community! We are thrilled to end our season with four amazing performances. Our wonderful spring concerts start with Peaks of Beauty and Devotion (March 6–7, Ohio Theatre). American artist Joshua Roman performs his own evocative Cello Concerto in a CSO premiere. Rossen Milanov conducts this powerful performance, culminating in Anton Bruckner’s majestic Symphony No. -

The Wanamaker Organ

MUSIC FOR ORGAN AND ORCHESTRA CTHeEn W AnN AiMaA k CERo OnRcGerA N PETER RICHARD CONTE, ORGAN SyMPHONy IN C • ROSSEN MIlANOv, CONDUCTOR tracklist Symphony No. 2 in A Major, for Organ and Orchestra, Opus 91 Félix Alexandre Guilmant 1|I. Introduction et Allegro risoluto 10:18 2|II. Adagio con affetto 5:56 3|III. Scherzo (Vivace) 6:49 4|IV. Andante Sostenuto 2:39 5|V. Intermède et Allegro Con Brio 5:55 6 Alleluja, for Organ & Orchestra, Opus 112 Joseph Jongen 5:58 7 Hymne, for Organ & Orchestra, Opus 78 Jongen 8:52 Symphony No. 6 in G Minor, for Organ and Orchestra, Opus 42b Charles-Marie Widor 8|I. Allegro Maestoso 9:21 9|II. Andante Cantabile 10:39 10 | III. Finale 6:47 TOTAL TIME : 73:16 2 3 the music FÉLIX ALEXANDRE GUILMANT Symphony No. 2 in A Major for Organ and Orchestra, Op. 91 Alexandre Guilmant (1837-1911), the renowned Parisian organist, teacher and composer, wrote this five- movement symphony in 1906. Two years before its composition, Guilmant played an acclaimed series of 40 recitals on the St. Louis World ’s Fair Organ —the largest organ in the world —before it became the nucleus of the present Wanamaker Organ. In the Symphony ’s first movement, Introduction et Allegro risoluto , a sprightly theme on the strings is offset by a deeper motif. That paves the way for the titanic entrance of full organ, with fugato expositions and moments of unbridled sensuousness, CHARLES-MARIE WIDOR building to a restless climax. An Adagio con affetto follows Symphony No 6 in G Minor in A-B-A form, building on the plaintive organ with silken for Organ and Orchestra, Op. -

Musical Biography of Brett Deubner, Violist As One of This Generation's

Musical Biography of Brett Deubner, violist As one of this generation's most consummate violists, Brett Deubner has received worldwide critical acclaim for his powerful intensity and sumptuous tone. Commenting on Mr. Deubner's performance the New Jersey Star-Ledger wrote, "Deubner played with dynamic virtuosity hitting the center of every note no matter how many there were." And, "There is a burning intensity to Deubner's playing, and a refreshing variation in the color of his viola tone." The Strad magazine cited his playing for its "infectious capriciousness," and Classical New Jersey praised him for being "extremely sensitive and expressive." As a graduate of the Eastman School of Music, Mr. Deubner's career has included frequent solo recitals, membership in top American orchestras, and chamber music collaborations worldwide. He has collaborated with today's leading conductors Ann Manson, Perry So, Lucas Richman, David Lockington, Patricio Aizaga, Oliver Weder, and Rossen Milanov. While collaborating on chamber music he has performed with the Tokyo Quartet and Vermeer Quartet, pianists Joseph Kallichstein and Robert Koenig, cellists Wendy Warner and Sara Sant'Amrogio, clarinetists Guy Deplus and Alexander Fiterstein, violinists Timothy Fain, Stefan Milenkovich, Gregory Fulkerson, and Dimitry Sitkovetsky, flutists Ransom Wilson and Carol Wincenc, New York Philharmonic principal oboist Joseph Robinson, and Dallas Symphony principal oboist Erin Hannigan. His recent concerto performances have traversed over four continents with forty orchestras, including the Grand Rapids Symphony, the Thüringer Symphoniker in Saalfeld-Rudolstadt, Germany, the New Jersey Symphony Orchestra, the Knoxville Symphony, the Grainger Wind Symphony in Melbourne, the Filharmonic del Quito, the String Orchestra of the Rockies, the National Symphony of Ecuador, the State Orchestra of Merida, Venezuela, the New Symphony of Sofia, Bulgaria, the Orchestra Bell'Arte of Paris, the Peninsula Symphony of California, and the Kiev Camerata in Ukraine. -

MATTHIAS PINTSCHER to Lead New York Philharmonic in NEW

Contact: Katherine E. Johnson (212) 875-5718; [email protected] National Press Representative: Julia Kirchhausen (917) 453-8386; [email protected] JUNE 6, 2014, AT AVERY FISHER HALL: MATTHIAS PINTSCHER To Lead New York Philharmonic in NEW YORK PREMIERES of His CELLO CONCERTO, Reflections on Narcissus, with Cellist ALISA WEILERSTEIN, and CARTER’S Instances Concert To Feature WORLD PREMIERE of Work Selected from National Open Call for Scores Facilitated by American Composers Orchestra’s EarShot Program As part of the NY PHIL BIENNIAL, conductor-composer Matthias Pintscher (Germany, b. 1971) leads the New York Philharmonic in his own Reflections on Narcissus, a cello concerto spotlighting cellist Alisa Weilerstein, followed by the last completed work by American icon Elliott Carter (United States, 1908–2012), June 6, 2014, in Avery Fisher Hall. Mr. Pintscher will open the concert with the World Premiere of one of three works by composers discovered through the assistance of the EarShot National Orchestral Composition Discovery Network. “It is very moving for me to be given the honor of performing Carter’s last finished orchestral composition, Instances, in New York, since he and the Philharmonic have a long history together,” Matthias Pintscher said. “When I was looking at the score for Instances, I was reminded of Giuseppe Verdi, as both he and Carter brought a lightness and freshness to the musical compositions of their old age. Carter’s music is beautifully transparent, highly expressive, and at ease with itself without ever losing its directness of expression. My own work on this program, Reflections on Narcissus, is less a cello concerto than a symphonic and virtuosic dialogue between a solo cello and a huge orchestra. -

JENNIFER KOH Biography Recognized for Intense

JENNIFER KOH Biography Recognized for intense, commanding performances, delivered with dazzling virtuosity and technical assurance, violinist Jennifer Koh is a forward-thinking artist dedicated to exploring a broad and eclectic repertoire, while promoting equity and inclusivity in classical music. She has expanded the contemporary violin repertoire through a wide range of commissioning projects and has premiered more than 100 works written especially for her. Her quest for the new and unusual, sense of endless curiosity, and ability to lead and inspire a host of multidisciplinary collaborators, truly set her apart. Her critically acclaimed series include Alone Together, Bach and Beyond, The New American Concerto, Limitless, Bridge to Beethoven, and Shared Madness. Coming this season to Carnegie’s Zankel Hall, the Kennedy Center, and Cincinnati’s Music Hall, The New American Concerto is Ms. Koh’s ongoing, multi-season commissioning project that explores the form of the violin concerto and its potential for artistic engagement with contemporary societal concerns and issues through commissions from a diverse collective of composers. In February and March 2022, she premieres Missy Mazzoli’s Violin Concerto with the National Symphony Orchestra conducted by Gemma New at the Kennedy Center and with the Cincinnati Symphony Orchestra conducted by Louis Langrée at Music Hall. Ms. Mazzoli’s concerto is the sixth to have been commissioned as part of the project, and Ms. Koh premieres the work having earlier in the season performed solo and chamber music by Ms. Mazzoli in San Francisco alongside the composer herself. Also in March 2022, Mr. Koh gives the New York premiere of Lisa Bielawa’s violin concerto Sanctuary at Carnegie’s Zankel Hall with the American Composers Orchestra. -

NFA 2021 Program Book Concert Programs 8 3 21

THURSDAY Annual Meeting and Opening Flute Orchestra Concert Thursday, August 12, 2021 9:00–10:00 AM CDT Adah Toland Jones, conductor Kathy Farmer, coordinator Valse, from Sleeping Beauty Pyotr Ilyich Tchaikovsky (1840–93) Out of the Chaos of My Doubt Gordon Jones (b. 1947) Interlude No. 1 Rêverie Claude Debussy (1862–1918) Out of the Chaos of My Doubt Gordon Jones (b. 1947) Interlude No. 2 Talisman Alexandra Molnar-Suhajda (b. 1975) Out of the Chaos of My Doubt Gordon Jones (b. 1947) Interlude No. 3 Sierra Morning Freedom Jonathan Cohen (b. 1954) 2. Peregrine Bugler’s Dream Leo Arnaud (1904–91) 7 Decades of Innovating the Imagined: Celebrating the Music of Robert Dick Thursday, August 12, 2021 10:00–11:00 AM CDT Flames Must Not Encircle Sides Robert Dick (b. 1950) Lisa Bost-Sandberg Afterlight Dick Bonnie McAlvin Fire's Bird Dick Mary Kay Fink Book of Shadows Dick Leonard Garrison, bass flute Time is a Two Way Street Dick I. II. Robert Dick and Melissa Keeling High School Soloist Competition Final Round: Part I Thursday, August 12, 2021 10:00–11:30 AM CDT Amy I-Yun Tu, coordinator Katie Leung, piano Recorded round judges: Brian Dunbar, Luke Fitzpatrick, Izumi Miyahara Final round judges: Julietta Curenton, Eric Lamb, Susan Milan, Daniel Velasco, Laurel Zucker Finalists in alphabetical order: Emily DeNucci Joanna Hsieh Choyi Lee Xiaoxi Li Finalists will perform the following works in the order of their choosing: For Each Inch Cut Andrew Rodriguez (b. 1989) World Premiere Valse Caprice Daniel S. Wood (1872–1927) Sonata Francis Poulenc (1899–1963) 1.