Spatial Patterns of Road Mortality of Medium„&Ndash;„Large Mammals In

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Pantanal, Brazil 12Th July to 20Th July 2015

Pantanal, Brazil 12th July to 20th July 2015 Steve Firth Catherine Griffiths This trip was an attempt to see some mammal species that had eluded us on many previous visits to South America. Cats were the main focus, specifically Jaguar and Ocelot, and we were hoping for Giant Anteater as a bonus. When we started planning the trip some ten months in advance, the exchange rate was £1 = R$3.8. The pound strengthened considerably in the intervening period and was £1 = R$5.0 during the visit. This helped to appreciably reduce costs . We flew from London to Campo Grande via Sao Paulo with TAM. There was a 10 hour stopover, but the flight was a great deal cheaper than any offered by other Airlines. On the return leg we flew from Cuiaba to London again via Sao Paulo, again with a long layover. The total Cost per person was £943.35. TAM proved to be more efficient than we had expected (we had had a few memorable difficulties with VARIG 15 years previously) and can be recommended. The Campo Grande to Cuiaba leg was flown with AZUL, booked via their website. The rate quoted, R$546.50 (£70.84 each at the time of booking) for two people, was actually charged to our credit card as US Dollars $546.50. This was noticed immediately and after a call to AZUL in Brazil, they swiftly refunded the first charge and debited the correct amount. AZUL are a low cost carrier, but this was not reflected in their service or punctuality. -

Redalyc.FIRST RECORD of PANTANAL CAT, Leopardus

Mastozoología Neotropical ISSN: 0327-9383 [email protected] Sociedad Argentina para el Estudio de los Mamíferos Argentina Díaz Luque, José A.; Beraud, Valerie; Torres, Pablo J.; Kacoliris, Federico P.; Daniele, Gonzalo; Wallace, Robert B.; Berkunsky, Igor FIRST RECORD OF PANTANAL CAT, Leopardus colocolo braccatus, IN BOLIVIA Mastozoología Neotropical, vol. 19, núm. 2, julio-diciembre, 2012, pp. 299-301 Sociedad Argentina para el Estudio de los Mamíferos Tucumán, Argentina Available in: http://www.redalyc.org/articulo.oa?id=45725085020 How to cite Complete issue Scientific Information System More information about this article Network of Scientific Journals from Latin America, the Caribbean, Spain and Portugal Journal's homepage in redalyc.org Non-profit academic project, developed under the open access initiative Mastozoología Neotropical, 19(2):299-301, Mendoza, 2012 ISSN 0327-9383 ©SAREM, 2012 Versión on-line ISSN 1666-0536 http://www.sarem.org.ar FIRST RECORD OF PANTANAL CAT, Leopardus colocolo braccatus, IN BOLIVIA José A. Díaz Luque1,2, Valerie Beraud2, Pablo J. Torres3, Federico P. Kacoliris2,4,5, Gonzalo Daniele2, Robert B. Wallace6, and Igor Berkunsky2,5,7 1 Urbanización el Coto, Calle Ruiseñor Nº6, 29651 Mijas Costa, Málaga, España [Correspondence: <[email protected]>]. 2 Proyecto de conservación de la Paraba Barba Azul, World Parrot Trust, Casilla 101, Trinidad, Beni, Bolivia. 3 Universidad Nacional de la Patagonia San Juan Bosco, Boulevard Brown 3700, Puerto Madryn, Chubut, Argentina. 4 División Vertebrados, Facultad de Ciencias Naturales y Museo, Universidad Nacional de La Plata, Paseo del Bosque s/n, B1900FWA La Plata, Argentina. 5 CONICET (Consejo Nacional de Investigaciones Científicas y Técnicas), Argentina. -

Leopardus Pajeros)

Jason Sweeney February 19, 2014 BBIO 485 Conservation Biology The Pampas Cat (Leopardus pajeros) Species Introduction: The Pampas cat (Leopardus pajeros) is a small feline found throughout many regions of South America. If the Pampas cat is being grouped together with other cats as a subspecies of Leopardus colocolo then the Pampas cat is found in almost all of South America. When the Pampas cat is classified as its own species then the range shrinks dramatically to mostly the eastern slopes of the Andes. Researchers have had a great deal of difficulty categorizing the species since it was first described in the early 1800s, and has belonged to a variety of different genera, as well as grouped or separated from other cat species in South America. (Garcia-Perea, 1994). The history of the Pampas cat’s classification has been long and confusing. Even to this day confusion on classification still exists. The Pampas Cat has been split into its own species (Leopardus pajeros), with several of its own subspecies, but many still consider it as a subspecies of the species L. colocolo. When grouped into the species of L. colocolo the group of cats, Pampas cat (L. pajeros), the Pantanal cat (Leopardus braccatus) of Brazil and the actual colocolo cat are all referred to as a group as the Pampas cat (Garcia-Perea, 1994) adding to the confusion when trying to gain information or classifying any of the group. The Pampas cat was split from this group due to differences in color of their fur and cranial sizes, a split which is not supported by genetic research (Garcia-Perea, 1994). -

I METHODS of NICHE PARTITIONING BETWEEN

METHODS OF NICHE PARTITIONING BETWEEN ECUADORIAN CARNIVORES AND HABITAT PREFERENCE OF THE MARGAY ( LEOPARDUS WIEDII ) Anne-Marie C. Hodge A Thesis Submitted to the University of North Carolina Wilmington in Partial Fulfillment for the Requirements for the Degree of Master of Science Department of Biology and Marine Biology University of North Carolina Wilmington 2012 Approved By: Advisory Committee Travis Knowles Steven Emslie Marcel van Tuinen Brian Arbogast Chair Accepted by Dean, Graduate School i TABLE OF CONTENTS ABSTRACT ................................................................................................................................... iv DEDICATION .................................................................................................................................v LIST OF TABLES ......................................................................................................................... vi LIST OF FIGURES ...................................................................................................................... vii CHAPTER 1: MARGAY ACTIVITY PATTERNS AND DENSITY............................................1 Introduction ..........................................................................................................................1 Methods................................................................................................................................5 Study Location .........................................................................................................5 -

Life on Land

Brazilian Agricultural Research Corporation Ministry of Agriculture, Livestock and Food Supply Sustainable Development Goal 15 LIFE ON LAND CONTRIBUTIONS OF EMBRAPA Gisele Freitas Vilela Michelliny Pinheiro de Matos Bentes Yeda Maria Malheiros de Oliveira Débora Karla Silvestre Marques Juliana Corrêa Borges Silva Technical Editors Translated by Paulo de Holanda Morais Embrapa Brasília, DF 2019 Embrapa Unit Responsible for publication Parque Estação Biológica (PqEB) Embrapa, General Division Av. W3 Norte (Final) 70770-901 Brasília, DF Editorial Coordination Phone: +55 (61) 3448-4433 Alexandre de Oliveira Barcellos www.embrapa.br Heloiza Dias da Silva www.embrapa.br/fale-conosco/sac Nilda Maria da Cunha Sette Unit responsible for the content Editorial Supervision Intelligence and Strategic Relations Division Wyviane Carlos Lima Vidal Technical Coordination of SDG Collection Text revision Valéria Sucena Hammes Ana Maranhão Nogueira André Carlos Cau dos Santos Letícia Ludwig Loder Local Publication Committee Bibliographic standardization Rejane Maria de Oliveira President Renata Bueno Miranda Translation Paulo de Holanda Morais Executive Secretary (World Chain Idiomas e Traduções Ltda.) Jeane de Oliveira Dantas Grafic project and cover Members Carlos Eduardo Felice Barbeiro Alba Chiesse da Silva Assunta Helena Sicoli Image processing Ivan Sergio Freire de Sousa Paula Cristina Rodrigues Franco Eliane Gonçalves Gomes Cecília do Prado Pagotto 1st Edition Claudete Teixeira Moreira Digitized publication (2019) Marita Féres Cardillo Roseane Pereira Villela Wyviane Carlos Lima Vidal All rights reserved. Unauthorized reproduction of this publication, in part or in whole, constitutes breach of copyright (Law 9,610). Cataloging in Publication (CIP) data Embrapa Life on land : Contributions of Embrapa / Gisele Freitas Vilela … [et al.], technical editors; tranlated by Paulo de Holanda Morais. -

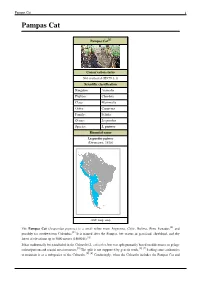

Pampas Cat 1 Pampas Cat

Pampas Cat 1 Pampas Cat Pampas Cat[1] Conservation status Not evaluated (IUCN 3.1) Scientific classification Kingdom: Animalia Phylum: Chordata Class: Mammalia Order: Carnivora Family: Felidae Genus: Leopardus Species: L. pajeros Binomial name Leopardus pajeros (Desmarest, 1816) crude range map The Pampas Cat (Leopardus pajeros) is a small feline from Argentina, Chile, Bolivia, Peru, Ecuador,[1] and possibly far southwestern Colombia.[2] It is named after the Pampas, but occurs in grassland, shrubland, and dry forest at elevations up to 5000 metres (16000 ft).[3] It has traditionally been included in the Colocolo (L. colocolo), but was split primarily based on differences in pelage colour/pattern and cranial measurements.[3] The split is not supported by genetic work,[4] [5] leading some authorities to maintain it as a subspecies of the Colocolo.[2] [6] Confusingly, when the Colocolo includes the Pampas Cat and Pampas Cat 2 Pantanal Cat as subspecies, the "combined" species is sometimes referred to as the Pampas Cat.[7] Pampas cats have not been studied much in the wild and little is known about their hunting habits. There have been reports of the cat hunting rodents and birds at night, and also hunting domestic poultry near farms. Subspecies In 2005, Mammal Species of the World recognised 5 subspecies of the Pampas Cat:[1] • Leopardus pajeros pajeros (nominate) – southern Chile and widely in Argentina.[6] • Leopardus pajeros crespoi – eastern slope of the Andes in northwestern Argentina.[3] • Leopardus pajeros garleppi – Andes in Peru.[3] • Leopardus pajeros steinbachi – Andes in Bolivia.[3] • Leopardus pajeros thomasi – Andes in Ecuador.[3] Based on two specimens of the subspecies steinbachi, it is larger and paler than garleppi. -

Os Nomes Galegos Dos Carnívoros 2019 2ª Ed

Os nomes galegos dos carnívoros 2019 2ª ed. Citación recomendada / Recommended citation: A Chave (20192): Os nomes galegos dos carnívoros. Xinzo de Limia (Ourense): A Chave. https://www.achave.ga"/wp#content/up"oads/achave_osnomes!a"egosdos$carnivoros$2019.pd% Fotografía: lince euroasiático (Lynx lynx ). Autor: Jordi Bas. &sta o'ra est( su)eita a unha licenza Creative Commons de uso a'erto* con reco+ecemento da autor,a e sen o'ra derivada nin usos comerciais. -esumo da licenza: https://creativecommons.or!/"icences/'.#n #nd//.0/deed.!". Licenza comp"eta: https://creativecommons.or!/"icences/'.#n #nd//.0/"e!a"code0"an!ua!es. 1 Notas introdutorias O que cont n este documento Neste documento fornécense denominacións galegas para diferentes especies de mamíferos carnívoros. Primeira edición (2018): En total! ac"éganse nomes para 2#$ especies! %&ue son practicamente todos os carnívoros &ue "ai no mundo! salvante os nomes das focas% e $0 subespecies. Os nomes galegos das focas expóñense noutro recurso léxico da +"ave dedicado só aos nomes das focas! manatís e dugongos. ,egunda edición (201-): +orríxese algunha gralla! reescrí'ense as notas introdutorias e incorpórase o logo da +"ave ao deseño do documento. A estrutura En primeiro lugar preséntase a clasificación taxonómica das familias de mamíferos carnívoros! onde se apunta! de maneira xeral! os nomes dos carnívoros &ue "ai en cada familia. seguir vén o corpo do documento! unha listaxe onde se indica! especie por especie, alén do nome científico! os nomes galegos e ingleses dos diferentes mamíferos carnívoros (nalgún caso! tamén, o nome xenérico para un grupo deles ou o nome particular dalgunhas subespecies). -

Leopardus Colocolo Braccatus, in BOLIVIA

Mastozoología Neotropical, 19(2):299-301, Mendoza, 2012 ISSN 0327-9383 ©SAREM, 2012 Versión on-line ISSN 1666-0536 http://www.sarem.org.ar FIRST RECORD OF PANTANAL CAT, Leopardus colocolo braccatus, IN BOLIVIA José A. Díaz Luque1,2, Valerie Beraud2, Pablo J. Torres3, Federico P. Kacoliris2,4,5, Gonzalo Daniele2, Robert B. Wallace6, and Igor Berkunsky2,5,7 1 Urbanización el Coto, Calle Ruiseñor Nº6, 29651 Mijas Costa, Málaga, España [Correspondence: <[email protected]>]. 2 Proyecto de conservación de la Paraba Barba Azul, World Parrot Trust, Casilla 101, Trinidad, Beni, Bolivia. 3 Universidad Nacional de la Patagonia San Juan Bosco, Boulevard Brown 3700, Puerto Madryn, Chubut, Argentina. 4 División Vertebrados, Facultad de Ciencias Naturales y Museo, Universidad Nacional de La Plata, Paseo del Bosque s/n, B1900FWA La Plata, Argentina. 5 CONICET (Consejo Nacional de Investigaciones Científicas y Técnicas), Argentina. 6 Wildlife Con- servation Society, 185th Street and Southern Boulevard, Bronx, New York, 10460, U.S.A. 7 Instituto Multidisciplinario sobre Ecosistemas y Desarrollo Sustentable, Universidad Nacional del Centro de la Provincia de Buenos Aires, Campus Universitario, Paraje Arroyo Seco, B7000GHG Tandil, Argentina. ABSTRACT: The Pantanal cat, Leopardus colocolo braccatus, has been reported for grasslands and subtropical humid forests in Brazil, Uruguay, Paraguay and Argentina. Here we report a dead Pantanal cat in the Moxos savannahs of the Beni Department of Bolivia, representing the first record of this taxon for Bolivia. This record, in combination with a reassessment of two previous records of L. colocolo in the lowlands of Bolivia, extends the distribution range of this subspecies ca.1000 km WNW from the nearest known locality in Brazil. -

Pantanal Checklist

PANTANAL CHECKLIST Birds English Name Portuguese Name Scientific Name Date Time Location # ID Anhinga Carará / biguatinga Anhinga anhinga Great ani Anu-coroca Crotophaga major Smooth-billed ani Anu-preto Crotophaga ani Mato grosso antbird Chororó-Do-Pantanal Cercomacra melanaria Barred antshrike Choca-Barrada Thamnophilus doliatus Great antshrike Taraba Major Taraba major Chestnut-eared araçari Araçari-Castanho Pteroglossus castanotis Chopi blackbird Gnorimopsar chopi Scarlet-headed blackbird Cardeal-Do-Banhado Amblyramphus holosericeus Shiny blackbird Molothrus bonariensis Solitary cacique Iraúna-De-Bico-Branco Cacicus solitaris Yellow-rumped cacique Cacicus Cela Cacicus cela Southern caracara Caracará Caracara plancus Yellow-billed cardinal Cardeal-Do-Pantanal Paroaria capitata Chaco chachalaca Aracuã-Do-Pantanal Ortalis canicollis Neotropical cormorant Biguá Phalacrocorax brasilianus Guira cuckoo Anu-Branco Guira guira Little cuckoo Piaya Minuta Coccycua minuta Squirrel cuckoo Piaya Cayana Piaya cayana Bare-faced curassow Mutum-De-Penacho Crax fasciolata Donacobius Japacanim Donacobius atricapilla Eared dove Avoante Zenaida auriculata Picui ground dove Rolinha-Picui Columbina picui Ruddy ground dove Rolinha-Roxa Columbina talpacoti Scaled dove Fogo-Apagou Scardafella squammata Black bellied whistling duck Marreca-Cabocla Dendrocygna autumnalis Muscovy duck Pato-Selvagem Cairina moschata White-faced whistling duck Irerê Dendrocygna viduata Cattle egret Bubulcus Ibis Bubulcus ibis Snowy egret Garça-Branca-Pequena Egretta thula Great -

GRASIELA EDITH DE OLIVEIRA PORFIRIO Ecologia E Conservação

Universidade de Aveiro Departamento de Biologia 2014 GRASIELA EDITH DE Ecologia e Conservação de felinos no Pantanal do OLIVEIRA PORFIRIO Brasil Ecology and Conservation of felids in the Brazilian Pantanal Universidade de Aveiro Departamento de Biologia 2014 Grasiela Edith de Ecologia e Conservação de felinos no Pantanal do Oliveira Porfirio Brasil Ecology and Conservation of felids in the Brazilian Pantanal Tese apresentada à Universidade de Aveiro para cumprimento dos requisitos necessários à obtenção do grau de Doutor em Biologia, ramo Ecologia, Biodiversidade e Gestão de Ecossistemas, realizada sob a orientação científica do Doutor Carlos Manuel Martins Santos Fonseca, Professor Auxiliar com agregação do Departamento de Biologia da Universidade de Aveiro e co- orientação do Doutor Pedro Sarmento, Técnico Superior do Instituto da Conservação da Natureza e das Florestas. Apoio financeiro da FCT (Bolsa de doutoramento SFRH/BD/51033), apoio financeiro e logístico do Instituto Homem Pantaneiro e Instituto Ecotropical, Brasil. Dedico esta tese ao meu avô José Porfirio Filho (In memorian) e à minha avó Maria Edith Batestti de Oliveira; Aos meus pais por todo o amor, zelo, dedicação, apoio, e incentivo; E a todos aqueles dedicam suas vidas para proteger e entender a natureza. o júri presidente Prof. Doutor José Carlos Esteves Duarte Pedro professor catedrático da Universidade de Aveiro Prof. Doutor Amadeu Mortágua Velho da Maia Soares professor catedrático da Universidade de Aveiro Prof. Doutor Carlos Manuel Martins Santos Fonseca professor auxiliar com agregação da Universidade de Aveiro Prof. Doutor Pedro Bernardo Marques da Silva Rodrigues Sarmento técnico superior do Instituto da Conservação da Natureza e das Florestas Prof. -

1 M a M M a L S & R E P T I L E S We Aim to Be HALF-CATALOGUE PRICE

Updated 11.05.2021 M a m m a l s & R e p t i l e s PHILATELIC SUPPLIES (M.B.O'Neill) 359 Norton Way South Letchworth Garden City HERTS ENGLAND SG6 1SZ (Telephone 0044-(0)1462-684191 during office hours 9.30-3.-00pm UK time Mon.-Fri.) Web-site: www.philatelicsupplies.co.uk email: [email protected] TERMS OF BUSINESS: & Notes on these lists: (Please read before ordering). 1). All stamps are unmounted mint unless specified otherwise. All list prices are in Pounds Sterling (£) we aim to be HALF-CATALOGUE PRICE OR UNDER 2). Lists are updated about every month to include most recent stock movements and New Issues; they are therefore reasonably accurate stockwise 100% pricewise. This reduces the need for "credit notes" or refunds. Alternatives may be listed in case an item is out of stock However, these popular lists are still best used as soon as possible. Next listings will be printed in 4, 8 & 12 months time, so please say when next we should send a list. 3). New Issues Services can be provided if you wish to keep your collection up to date on a Standing Order basis. Details & forms on request. Regret we do not run an on approval service. 4). All orders on our order forms are attended to by return of post. We will keep a photocopy of it and return your annotated original. 5). Other Thematic Lists are available on request; Birds, Butterflies, all Flora & fauna... 6). POSTAGE is extra and we use current G.B.commemoratives in complete sets where possible for postage. -

Nameri National Park

INDIA Date - February 2017 Duration - 25 Days Destinations Kolkata - Guwahati - Nameri National Park - Pakke Wildlife Sanctuary - Eaglenest Wildlife Sanctuary - Kaziranga National Park - Jorhat - Hoollongapar Gibbon Sanctuary - Dehing Patkai Wildlife Sanctuary Trip Overview This was meant to be the first of a number of spectacular tours in 2017 and the fact that it did not proceed as planned, highlights not only some of the difficulties involved with remote wildlife travel, but, more specifically, what can go wrong when you visit certain areas of India. I had been working on this trip for some time, as Arunachal Pradesh and Assam, the two states that I would visit on this tour, plus the bordering states of Nagaland and Manipur, which I intended to explore the following year, are all home to an astounding variety of rare mammals and the entire region is one of the most diverse in all of South Asia. Of the eight cat species that occur in this part of northeast India, I was hoping to encounter clouded leopard, Asiatic golden cat and marbled cat on this one tour and other very real possibilities included sun bear, Asiatic black bear, sloth bear, dhole, binturong, spotted linsang, large Indian civet, masked palm civet, small-toothed palm civet, yellow-throated marten, Asian small-clawed otter, hog badger, large-toothed ferret badger, small- toothed ferret badger, Bengal slow loris, Malayan porcupine and Chinese pangolin. A red panda sighting was also a realistic prospect and although we would not reach there on this occasion, further north in Arunachal Pradesh, Eurasian lynx and snow leopards increase the cat tally in this extraordinary region to an equally remarkable ten.