Part I the HEDGE FUND MANAGERS

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

View Annual Report

INVESTING FOR GROWTH Devro plc Annual Report & Accounts 2013 What’s inside this 2013 Highlights Annual Report Section 1 Strategic Report DEVRO IS ONE OF THE 2013 Highlights .................................. IFC Devro’s Business at a Glance .......... 2 WORLD’S LEADING Understanding Our Markets ........... 4 Our Strategy ............................................. 6 Key Performance Indicators ......... 14 SUPPLIERS OF COLLAGEN Chairman’s Statement ..................... 16 Chief Executive’s Review ................ 18 FOOD CASINGS Financial Review ................................ 23 Principal Risks and Uncertainties .............................. 28 Corporate Social Responsibility Report ..................... 32 Section 2 Revenue* Operating profit Report of Directors before exceptional items* Directors and Senior Management .......................... 38 £242.7m £42.1m Corporate Governance Report ... 40 Audit Committee Report ............... 47 241.1 Remuneration Report ..................... 50 242.7 227.7 42.5 42.4 42.1 Directors’ Report ............................... 64 213.6 197.4 36.2 Section 3 26.2 Financial Statements Consolidated Income Statement .............................................. 69 ‘09 ‘10 ‘11 ‘12 ‘13 ‘09 ‘10 ‘11 ‘12 ‘13 Statement of Comprehensive Income ................ 70 Balance Sheets .................................... 71 Statements of Changes in Equity .................................................. 72 Cash Flow Statements ................... 74 Earnings per share Dividends per share Notes to the Financial -

Full Year Results for the Year Ended 31 December 2018

PRELIMINARY RESULTS PRESENTATION | FOR THE YEAR ENDED 31 DECEMBER 2018 26 FEBRUARY 2019 FULL YEAR RESULTS FOR THE YEAR ENDED 31 DECEMBER 2018 SIGNIFICANT PROGRESS ON STRATEGIC PRIORITIES AND IMPROVED PROFIT MARGIN 2018 HIGHLIGHTS • Continued progress on operational and strategic priorities Operational improvements across all manufacturing sites Substantially increased yields in the US Over-delivered Devro 100 savings £4.5m Launched Fine Ultra product platform in Japan, South East Asia and Europe – platform for growth China: updated commercial strategy and improved customer mix with ASP* up 16% 3Cs strategy defined and being implemented: new operating model and now fully integrated global organisation • Constant currency revenue flat with improved profit margin Edible casings group volumes flat due to market issues in Russia and Japan – excluding Russia and Japan 3% growth Growth in edible casings aligned with segmentation – revenue up 2% at constant currency due to country mix and in China customer mix Overall revenue in constant currencies flat with increases in edible casings offset by other products EBIT before exceptional and non-recurring items up 5% and margin up 100bps to 15.8% 1 * ASP – Average Selling Price EUROPE 43% Group revenue Continental EU UK & Ireland Russia & East Price/mix & FX • 2018 volume: + 4% • 2018 volume: -3% • 2018 volume: -12% • Price/mix: +0.5% • Particularly strong growth in • Slight decline after • Volumes sensitive to FX • FX: +1% due to Germany and Portugal strong 2017 movements – adverse in weakening -

2018 Annual Report

Devro plc Annual Report and Accounts 2018 DEVRO PLC Annual Report and Accounts 2018 My first year as CEO has been insightful and has only served to increase my appreciation of the opportunity ahead. In addition to the strategic priorities as set out at the start of the year it has been my priority to provide clear focus on delivery of profitable growth and to create a culture and mind-set of a global business. Rutger Helbing, CEO Business Review on page 10 > OUR 3Cs STRATEGY WIN WITH THE FOCUS ON CORE STRENGTHEN WINNING CUSTOMERS PROFITABILITY DRIVERS COMPETENCIES Devro will deliver superior customer We will improve our margins through By investing in our technology experience through innovative providing the capacity to underpin and science, and promoting external quality products adapted to local our revenue growth ambition as partnerships, we will strengthen customer needs, expert technical well as through continued focus on our long-term competitiveness. support and the capability to assist cost savings opportunities across our customers to bring innovations the business. to their markets. Success in the Cost optimisation The Devro Academy snacking market Page 16 > Page 19 > Page 15 > WHO WE ARE AND WHAT WE DO Page 2 > Strategic Report Directors Report Financial Statements Shareholder Information Highlights of the year Revenue (£’m) Strategic Report Highlights of the year ...........................1 £253.4m Devro at a glance ...................................2 Devro investment case .......................4 2018 253.4 Business model -

Devro Plc AUDITED FULL YEAR RESULTS for the YEAR ENDED 31 DECEMBER 2020

For Immediate Release 2 March 2021 Devro plc AUDITED FULL YEAR RESULTS FOR THE YEAR ENDED 31 DECEMBER 2020 Good strategic progress, improved profitability and robust cash delivery Devro plc (“Devro” or the “Group”), one of the world’s leading manufacturers of collagen products for the food industry, announces its results for the year ended 31 December 2020. Underlying results* Statutory results 2020 2019 2020 2019 Revenue (£m) 247.6 250.0 247.6 250.0 Operating profit/(loss) (£m) 40.8 39.1 36.2 (14.0) Operating profit margin (%) 16.5% 15.6% 14.6% (5.6)% Profit/(loss) before tax (£m) 35.4 33.1 29.4 (21.8) Basic earnings per share (pence) 16.5p 15.2p 13.8p (24.8)p Total dividend per share (pence) 9.0p 9.0p 9.0p 9.0p * Underlying figures are stated before exceptional items and net finance cost on pensions (see Alternative Performance Measures section of the Financial Review for definitions, explanation, and reconciliation to equivalent statutory measures). Financial Highlights • Volume of edible collagen casings increased 1% o Emerging markets up 13%: driven by Latin America, Russia and South East Asia, reflecting our targeted growth agenda o Mature markets down 5%: growth of 9% in North America offset by COVID-19 related decline in food services sector and distributor destocking in Europe o COVID-19 negative impact estimated at 2% • Group revenue marginally lower than prior year due to adverse mix and other products declining • Underlying operating profit of £40.8m, up 4% on prior year, and operating margin increased 90 bps to 16.5% benefiting from cost savings • Underlying basic earnings per share up 9% to 16.5p (2019: 15.2p) • Robust free cash flow generation leading to covenant net debt i of £109.5m (2019: £123.8m), representing net debt to EBITDA ii of 1.8x (2019: 1.9x) • Proposed final dividend of 6.3p. -

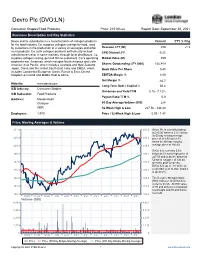

Devro Plc (DVO:LN)

Devro Plc (DVO:LN) Consumer Staples/Food Products Price: 215.00 GBX Report Date: September 28, 2021 Business Description and Key Statistics Devro and its subsidiaries is a manufacturers of collagen products Current YTY % Chg for the food industry. Co. supplies collagen casings for food, used by customers in the production of a variety of sausages and other Revenue LFY (M) 250 -1.3 meat products. Co. sells collagen products both directly to food EPS Diluted LFY -0.25 manufacturers and, in some markets, through local distributors. Co. supplies collagen casing, gel and film to customers. Co.'s operating Market Value (M) 359 segments are: Americas, which includes North America and Latin America; Asia Pacific, which includes Australia and New Zealand, Shares Outstanding LFY (000) 166,949 Japan, China and the rest of South East Asia; and EMEA, which Book Value Per Share 0.45 includes Continental European Union, Russia & East, United Kingdom & Ireland and Middle East & Africa. EBITDA Margin % 5.00 Net Margin % -16.7 Website: www.devro.com Long-Term Debt / Capital % 66.4 ICB Industry: Consumer Staples Dividends and Yield TTM 0.15 - 7.12% ICB Subsector: Food Products Payout Ratio TTM % 0.0 Address: Moodiesburn Glasgow 60-Day Average Volume (000) 224 GBR 52-Week High & Low 227.50 - 146.40 Employees: 1,970 Price / 52-Week High & Low 0.95 - 1.47 Price, Moving Averages & Volume 231.6 231.6 Devro Plc is currently trading at 215.00 which is 2.3% below its 50 day moving average 220.4 220.4 price of 219.99 and 9.3% above its 200 day moving 209.3 209.3 average price of 196.63. -

Premium Listed Companies Are Subject to the UK's Super-Equivalent Rules Which Are Higher Than the EU Minimum "Standard Listing" Requirements

List of Premium Equity Comercial Companies - 29th April 2020 Definition: Premium listed companies are subject to the UK's super-equivalent rules which are higher than the EU minimum "standard listing" requirements. Company Name Country of Inc. Description of Listed Security Listing Category Market Status Trading Venue Home Member State ISIN(S) 4IMPRINT GROUP PLC United Kingdom Ordinary Shares of 38 6/13p each; fully paid Premium Equity Commercial Companies RM LSE United Kingdom GB0006640972 888 Holdings Plc Gibraltar Ordinary Shares of 0.5p each; fully paid Premium Equity Commercial Companies RM LSE United Kingdom GI000A0F6407 AA plc United Kingdom Ordinary Shares of 0.1p each; fully paid Premium Equity Commercial Companies RM LSE United Kingdom GB00BMSKPJ95 Admiral Group PLC United Kingdom Ordinary Shares of 0.1p each; fully paid Premium Equity Commercial Companies RM LSE United Kingdom GB00B02J6398 AGGREKO PLC United Kingdom Ordinary Shares of 4 329/395p each; fully paid Premium Equity Commercial Companies RM LSE United Kingdom GB00BK1PTB77 AIB Group Plc Ireland Ordinary Shares of EUR0.625 each; fully paid Premium Equity Commercial Companies RM LSE Ireland IE00BF0L3536 Air Partner PLC United Kingdom Ordinary Shares of 1p each; fully paid Premium Equity Commercial Companies RM LSE United Kingdom GB00BD736828 Airtel Africa plc United Kingdom Ordinary Shares of USD0.50 each; fully paid Premium Equity Commercial Companies RM LSE United Kingdom GB00BKDRYJ47 AJ Bell plc United Kingdom Ordinary Shares of GBP0.000125 each; fully paid Premium -

Devro Plc Annual Report and Accounts 2015 Accounts and Report Annual

Devro plc Devro Annual Report and Accounts 2015 Devro plc Annual Report and Accounts 2015 Highlights of the year Devro is one of Group revenue* (£m) the world’s leading £230.2m 2015 230.2 manufacturers of 232.3 2014 collagen products for 2013 242.7 2012 241.1 the food industry 2011 227.7 Operating profit before exceptional items* (£m) £33.3m 2015 33.3 2014 30.3 2013 42.1 2012 42.4 2011 42.5 Earnings per share before exceptional items* (pence) 15.4p 2015 15.4 2014 13.7 2013 20.8 2012 19.4 2011 19.9 Dividends per share (pence) 8.8p 2015 8.8 2014 8.8 2013 8.8 2012 8.5 2011 8.0 * Continuing operations, and restated for revised pensions devro.com/investors/annualreport2015 accounting rules (IAS 19R) where relevant. 2015 WAS A YEAR OF NOTABLE Report Strategic PROGRESS WITH OUR TRANSFORMATION ON TRACK FOR COMPLETION IN 2016 Directors’ ReportDirectors’ We’re focused on revenue growth Page 8 in developed and emerging markets, while optimising manufacturing efficiency Page 10 Page 12 and ensuring product differentiation Statements Financial through research and development. Shareholder Information Shareholder Strategic Directors’ Financial Shareholder Report Report Statements Information Highlights of the year .......................IFC Directors and Senior Consolidated Notice of Annual Devro at a glance ............................... 2 Management ...................................... 34 income statement ............................63 General Meeting ..............................118 Understanding our markets ..........4 Corporate Governance Consolidated statement Explanatory notes Report ................................................... 36 of comprehensive income........... 64 to the AGM notice ..........................120 Our strategy .......................................... 6 Audit Committee Report ............. 43 Balance sheets...................................65 Shareholder information.............124 Our strategy in action ..................... -

Building for the Future

BUILDING FOR THE FUTURE Devro plc Annual Report & Accounts 2014 2014 HIGHLIGHTS DEVRO IS ONE OF THE WORLD’S LEADING MANUFACTURERS OF COLLAGEN FOOD PRODUCTS Group Revenue* Operating profit Earnings per share Dividends per share before exceptional items* before exceptional items* £232.3m £30.3m 13.7p 8.8p 241.1 242.7 8.8 8.8 232.3 9 8.5 227.7 4 42.1 42.5 42.4 8.0 213.6 20.8 19. 19. 6 7.0 36.2 16. 7 30.3 13. ‘10 ‘11 ‘12 ‘13 ‘14 ‘10 ‘11 ‘12 ‘13 ‘14 ‘10 ‘11 ‘12 ‘13 ‘14 ‘10 ‘11 ‘12 ‘13 ‘14 *Continuing operations, and restated for revised pensions accounting rules (IAS 19R) where relevant. Strategic Report of Financial Shareholder Report Directors Statements Information 2014 Highlights ................................. IFC Directors and Consolidated Income Notice of AGM ...................................... 116 Devro at a Glance ................................. 2 Senior Management .......................... 28 Statement ............................................... 58 Explanatory Notes Understanding Our Markets ........... 4 Corporate Governance Report ... 30 Consolidated Statement to the AGM Notice .............................. 118 of Comprehensive Income .......... 59 Our Strategy ............................................. 6 Audit Committee Report ............... 36 Shareholder Information .............. 122 Balance Sheets ................................... 60 Key Performance Indicators ........... 7 Directors’ Remuneration Directors and Advisers .................. IBC Report ...................................................... 39 -

Devro Plc HALF YEAR RESULTS for the SIX MONTHS ENDED 30 JUNE 2019

For Immediate Release 31 July 2019 Devro plc HALF YEAR RESULTS FOR THE SIX MONTHS ENDED 30 JUNE 2019 H1 results in line with Board’s expectations, good progress on strategic priorities and full year outlook unchanged Devro plc (“Devro” or the “group”), one of the world’s leading manufacturers of collagen products for the food industry, announces its half year results for the six months ended 30 June 2019. Underlying results* Statutory results H1 2019** H1 2018 H1 2019** H1 2018 Unaudited Unaudited Unaudited Unaudited Revenue £119.2m £120.2m £119.2m £120.2m Operating profit - - £17.4m £16.2m before non-recurring items*** £17.8m £18.8m - - Operating profit margin - - 14.6% 13.5% before non-recurring items*** 14.9% 15.6% - - Profit before tax £14.9m £14.3m £13.6m £10.9m Basic earnings per share 7.0p 6.6p 6.5p 4.7p Interim dividend per share 2.7p 2.7p 2.7p 2.7p * Underlying figures are stated before exceptional items and net finance cost on pensions (see Alternative Performance Measures section of the Half Year Results Update for definition, explanation and reconciliation to equivalent statutory measures). ** The group adopted IFRS 16 (leases) on 1 January 2019, as disclosed in note 3 to the condensed interim consolidated financial statements and comparative financial measures have not been restated. *** Non-recurring items relate to Board change costs of £nil (H1 2018: £0.4m); after non-recurring items underlying operating profit was £17.8m for H1 2019 (H1 2018: £18.4m); see Alternative Performance Measures section of the Half Year Results Update for definition and explanation. -

Results Presentation

HALF YEAR RESULTS FOR THE SIX MONTHS ENDED 30 JUNE 2020 29 JULY 2020 2 H1 HIGHLIGHTS • Good progress on strategic priorities despite Covid-19 impact • Emerging markets volumes up 19% - in line with growth agenda • Mature markets volumes down 6% - impacted by European destocking and Q2 Covid-19 • Continued delivery of cost savings - Bellshill site closed and project on track • EBIT up 4%, margin up 60 bps and free cash flow up 67% • Net debt £122.1m (June 2019: £149.2m) • Underlying basic earnings per share 7.5p (June 2019: 7.0p) • Interim dividend 2.7p, second interim dividend 6.3p 3 COVID-19 UPDATE GUIDING PRIORITIES Supply Make • Supply maintained throughout • All sites have operated throughout 01 period despite some challenges the pandemic – production Health and safety of mainly related to hides maintained at planned levels our colleagues and the • Temporary additional costs to • Strict protective measures including communities we live in manage supply in Q2 offset by H&S rules and quarantine processes cost savings 02 Contribute in a positive way to the food supply chain Demand • Q1 Retail demand elevated 03 • Q2 impacted by lower food service demand and temporary customer supply chain Maintain a robust interruptions in North America financial position • Net negative volume impact in H1 of 1.5% 4 MATURE MARKETS Protein snacking growth 72% GROUP REVENUE • North America +11% albeit volume growth lower than anticipated due to Covid-19 impact Continued distributor inventory destocking in Europe Covid-19 impact • Elevated retail demand -

International & Global Funds

Semi-Annual Report April 30, 2021 International & Global Funds Retirement Institutional Administrative Investor Class Class Class Class Harbor Diversified International All Cap Fund HNIDX HAIDX HRIDX HIIDX Harbor Emerging Markets Equity Fund HNEMX HAEMX HREMX HIEEX Harbor Focused International Fund HNFRX HNFSX HNFDX HNFIX Harbor Global Leaders Fund HNGIX HGGAX HRGAX HGGIX Harbor International Fund HNINX HAINX HRINX HIINX Harbor International Growth Fund HNGFX HAIGX HRIGX HIIGX Harbor International Small Cap Fund HNISX HAISX HRISX HIISX Harbor Overseas Fund HAORX HAOSX HAOAX HAONX Table of Contents Letter from the Chairman ............................................... 1 International & Global Funds HARBOR DIVERSIFIED INTERNATIONAL ALL CAP FUND Manager’s Commentary . ............................................... 2 Portfolio of Investments . .......... 4 HARBOR EMERGING MARKETS EQUITY FUND Manager’s Commentary . ............................................... 12 Portfolio of Investments . .......... 14 HARBOR FOCUSED INTERNATIONAL FUND Manager’s Commentary . ............................................... 18 Portfolio of Investments . .......... 20 HARBOR GLOBAL LEADERS FUND Manager’s Commentary . ............................................... 22 Portfolio of Investments . .......... 24 HARBOR INTERNATIONAL FUND Manager’s Commentary . ............................................... 26 Portfolio of Investments . .......... 28 HARBOR INTERNATIONAL GROWTH FUND Manager’s Commentary . ............................................... 35 Portfolio -

M Funds Quarterly Holdings 3.31.2021*

M International Equity Fund 31-Mar-21 CUSIP SECURITY NAME SHARES MARKET VALUE % OF TOTAL ASSETS 233203421 DFA Emerging Markets Core Equity P 2560482 65394713.22 30.55% 712387901 Nestle SA, Registered 22264 2481394.23 1.16% 711038901 Roche Holding AG 4932 1593905.09 0.74% 690064001 Toyota Motor Corp. 20300 1579632.42 0.74% ACI02GTQ9 ASML Holding NV 2066 1252586.68 0.59% 780087953 Royal Bank of Canada 12100 1115641.76 0.52% 406141903 LVMH Moet Hennessy Louis Vuitton S 1624 1081926.46 0.51% 710306903 Novartis AG, Registered 12302 1051296.13 0.49% 677062903 SoftBank Group Corp. 11100 935317.23 0.44% 682150008 Sony Corp. 8500 890110.63 0.42% ACI07GG13 Novo Nordisk A/S, Class B 12082 818545.62 0.38% 552902900 Daimler AG, Registered 9159 816405.12 0.38% B15C55900 TOTAL SE 16933 789825.28 0.37% 621503002 Commonwealth Bank of Australia 11972 782935.95 0.37% B03MM4906 Royal Dutch Shell Plc, Class B 41803 769354.91 0.36% 891160954 Toronto-Dominion Bank (The) 11275 735337.79 0.34% 098952906 AstraZeneca Plc 7325 731819.38 0.34% B4TX8S909 AIA Group, Ltd. 60200 730227.29 0.34% 584235907 Deutsche Telekom AG, Registered 32806 660557.31 0.31% 614469005 BHP Group, Ltd. 19147 658802.61 0.31% B288C9908 Iberdrola SA 50592 651731.69 0.30% 071887004 Rio Tinto Plc 7931 606818.69 0.28% BLRB26905 Unilever Plc 9584 534759.09 0.25% 079805909 BP Plc 129795 527232.81 0.25% 559222955 Magna International, Inc. 5972 525965.59 0.25% 023740905 Diageo Plc 12494 514918.00 0.24% 064149958 Bank of Nova Scotia (The) 8200 512997.53 0.24% 618549901 CSL, Ltd.