Real-Life Experiences of the Poverty Premium

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Draftrail Strategy

South Yorkshire Passenger Transport Authority DRAFT RAIL STRATEGY Consultation Draft – October 2008 South Yorkshire, Making Rail a Better Choice 1 South Yorkshire, Making Rail a Better Choice Contents Contents Page Executive Summary 4 1. Introduction 5 2. The Rail Strategy in Context 9 National Context 10 Regional Context 10 Context Diagram 10 Strategy Objectives 11 3. Current Conditions 13 South Yorkshire Network 13 Local Network 13 Express Long Distance 15 Open Access 17 Freight 18 Rolling Stock 21 Train Capacity 23 South Yorkshire Stations 24 Access to Stations 28 Network Performance 29 Network Constraints 32 Ticketing and Pricing 34 Recent Land Use and Demand Changes 35 4. Recent Research 37 5. Future Conditions 39 Future Demand 39 New Stations 40 New Lines 41 Delivery Priorities 43 6. Action Plan 43 Details of Delivery/Funding 43 7. Monitoring and Consultation 46 Details of current Monitoring 46 Reporting processes 46 Consultation 48 2 Appendix One – The Rail Strategy in Context Appendix Two – Network Diagram/Map Appendix Three – Current Station Standards and Facilities Appendix Four – Proposed Housing Growth related to Rail Stations Appendix Five – Network bottlenecks and scheme dependencies Appendix Six – Delivery Plan 3 Executive Summary Executive Summary South Yorkshire, Making Rail a Better Choice To be drafted once contents are endorsed 4 Chapter 1 Introduction South Yorkshire, Making Rail a Better Choice Summary This document brings together changes in contextual policy and investment plans and Identifies the role of the Rail Strategy Provides an update on work completed since 2004 Summarises key developments and the effect on rail users Links all the above to explain the need for change Provides the planned actions to take the Strategy forward in the short, medium and long term 1.1 This Rail Strategy is produced by South Yorkshire Passenger Transport Executive (SYPTE), on behalf of South Yorkshire Passenger Transport Authority (SYPTA) and represents an update of the previous strategy issued in 2004. -

Goldthorpe and Bolton Upon Dearne Expansion

South Yorkshire Historic Environment Characterisation Project Barnsley Character Zone Descriptions Planned Industrial Settlements Areas within this Zone ‘Goldthorpe and Bolton Upon Dearne Expansion’, ‘Royston Miners Housing’, ‘Shafton Miners Housing’, ‘Brierley Colliery Housing’, ‘Carlton Miners Housing’, ‘Cudworth Miners Housing’, ‘Grimethorpe’, ‘Great Houghton Colliery Housing’, ‘Thurnscoe Colliery Village’, ‘Staincross Planned Colliery Housing’, ‘Middlecliff’, ‘Darton and Kexbrough Miners Housing’, ‘Penistone Industrial Expansion’, ‘Dodworth Colliery Housing’, ‘Planned Wombwell’, ‘Hoyland, Jump and Elsecar Planned Expansion’, ‘Darfield Planned Housing’, ‘Bolton Upon Dearne Miners Housing’, ‘Stairfoot Planned Housing’ Summary of Dominant Character As the coal seams are near to the surface in the west of the district they could be utilised from an early date and documentary evidence puts coal mining back as far as the medieval period. However, it wasn’t until between 1550 and 1700 that the industry expanded (Hill 2001, 54). These early mines were shallow, relatively small scale, short-lived operations because there were few transport links beyond local markets. These mines left few traces on the landscape and many did not survive long enough to be marked on the 1850s Ordnance Survey maps. This style of mining continued into the early 19 th century but the coming of railways in the mid 19 th and 20 th century and the building of the canals facilitated greater expansion. The greatest density of coal seams in the South Yorkshire coalfield was along the centre of the coal measures running through the east of Barnsley. This meant that although these seams had been worked for half a century longer than the concealed coal measures east of Barnsley there were similar reserves remaining (ibid, 14). -

Goldthorpe and Bolton on Dearne Partnership Board Big Local Plan 2015 – 2018 April 2015

GOLDTHORPE AND BOLTON ON DEARNE PARTNERSHIP BOARD BIG LOCAL PLAN 2015 – 2018 APRIL 2015 Parish Church Goldthorpe Dearne Playhouse Goldthorpe Centre 1 CONTENTS Section One Introduction to Goldthorpe and Bolton on Dearne Big Local Page 1 Section Two Our Overall Role and Approach Page Section Three Shared vision Page Section Four Priorities Page Section Five Outcomes Page Section Six Action Plan Page Section Seven Communications Page Section Eight Goldthorpe and Bolton on Dearne Big Local Plan for our Entire Community Page Section Nine Real issues and Big Challenges Page Section Ten Budgets Page 2 List of Figures Figure 1 Big Local Pathway Page Figure 2 Map of the area Page Figure 3 Our Themes and Outcomes Page List of Appendices Appendix 1 List of Partnership members Appendix 2 Area Profile for Goldthorpe and Bolton on Dearne Big Local Area Appendix 3 ‘It’s time to turn your ideas into our Big Local Plan’ Appendix 4 Example Cinema Posters Appendix 5 Big Local Leaflet 3 Glossary of terms The Big Local Plan – This document Area Profile for Goldthorpe and Bolton on Dearne Big Local Area – the document produced from all the views from the community consultation, visioning events and statistics which helped draw up the Big Local Plan Communications Plan – the different ways we use to try and let as many people as possible know what is happening Action Plan – details of how we will make the plan happen. Each theme/project has an action plan Outcomes – what has changed by implementing the things in the plan 4 SECTION ONE INTRODUTION TO GOLDTHORPE -

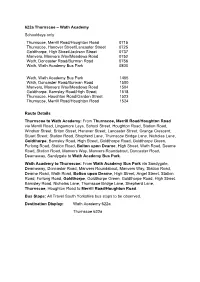

622A Thurnscoe – Wath Academy

622a Thurnscoe – Wath Academy Schooldays only Thurnscoe, Merrill Road/Houghton Road 0715 Thurnscoe, Hanover Street/Lancaster Street 0725 Goldthorpe, High Street/Jackson Street 0737 Manvers, Manvers Way/Meadows Road 0752 Wath, Doncaster Road/Burman Road 0756 Wath, Wath Academy Bus Park 0800 Wath, Wath Academy Bus Park 1455 Wath, Doncaster Road/Burman Road 1500 Manvers, Manvers Way/Meadows Road 1504 Goldthorpe, Barnsley Road/High Street 1518 Thurnscoe, Houghton Road/Garden Street 1523 Thurnscoe, Merrill Road/Houghton Road 1524 Route Details Thurnscoe to Wath Academy: From Thurnscoe, Merrill Road/Houghton Road via Merrill Road, Lingamore Leys, School Street, Houghton Road, Station Road, Windsor Street, Briton Street, Hanover Street, Lancaster Street, Grange Crescent, Stuart Street, Station Road, Shepherd Lane, Thurnscoe Bridge Lane, Nicholas Lane, Goldthorpe, Barnsley Road, High Street, Goldthorpe Road, Goldthorpe Green, Furlong Road, Station Road, Bolton upon Dearne, High Street, Wath Road, Dearne Road, Station Road, Manvers Way, Manvers Roundabout, Doncaster Road, Dearneway, Sandygate to Wath Academy Bus Park. Wath Academy to Thurnscoe: From Wath Academy Bus Park via Sandygate, Dearneway, Doncaster Road, Manvers Roundabout, Manvers Way, Station Road, Dearne Road, Wath Road, Bolton upon Dearne, High Street, Angel Street, Station Road, Furlong Road, Goldthorpe, Goldthorpe Green, Goldthorpe Road, High Street, Barnsley Road, Nicholas Lane, Thurnscoe Bridge Lane, Shepherd Lane, Thurnscoe, Houghton Road to Merrill Road/Houghton Road. Bus Stops: All Travel South Yorkshire bus stops to be observed. Destination Display: Wath Academy 622a Thurnscoe 622a . -

Goldthorpe and the Dearne Towns Green Belt Review

Barnsley Metropolitan Borough Council Barnsley Green Belt Review Green Belt: Goldthorpe (Dearne Towns) 01 Issue | August 2014 This report takes into account the particular instructions and requirements of our client. It is not intended for and should not be relied upon by any third party and no responsibility is undertaken to any third party. Job number 233367-00 Ove Arup & Partners Ltd 13 Fitzroy Street London W1T 4BQ United Kingdom www.arup.com Barnsley Metropolitan Borough Council Barnsley Green Belt Review Green Belt: Goldthorpe (Dearne Towns) Contents Page 1 Introduction 1 2 Assessment of Green Belt ‘General Areas’ 3 2.1 Introduction 3 2.2 Approach 3 3 General Area DE1 5 3.1 Stage 1: DE1 Green Belt Assessment Proforma 5 3.2 Introduction 5 3.3 Stage 2: Technical Site Assessment 11 3.4 Stage 3: Evaluating the Potential Newly Defined Green Belt Boundary 14 3.5 Conclusion for DE1 15 4 DE2 ‘General Area’ 17 4.1 Stage 1: DE2 Site Assessment Proforma 17 4.2 Conclusion for DE2 23 5 DE3 ‘General Area’ 24 5.1 Stage 1: DE3 General Area Assessment Proforma 24 5.2 Conclusion for DE3 30 6 DE4 ‘General Area’ 31 6.1 Stage 1: DE4 General Area Assessment Proforma 31 6.2 Conclusion for DE4 37 7 DE5 ‘General Area’ 38 7.1 Stage 1: DE5 Green Belt Assessment Proforma 38 7.1 Stage 2: Technical Site Assessment 44 7.2 Conclusion for DE5 46 8 DE6 ‘General Area’ 47 8.1 Stage 1: DE6 Green Belt Assessment Proforma 47 8.2 Conclusion for DE6 53 9 DE7 ‘General Area’ 54 9.1 Stage 1: DE7 Green Belt Assessment Proforma 54 9.2 Conclusion for DE7 60 10 Summary 61 01 | Issue | August 2014 J:\230000\233367-00\0 ARUP\0-06 PM\0-06-08 REPORTS\PHASE 1 GB REVIEW\BARNSLEY GREEN BELT REVIEW_RESULTANT LAND PARCELS\GOLDTHORPE - DEARNE TOWNS\BARNSLEY GREEN BELT REVIEW - GOLDTHORPE AND DEARNE TOWNS ISSUE 2014.DOCX Barnsley Metropolitan Borough Council Barnsley Green Belt Review Green Belt: Goldthorpe (Dearne Towns) 1 Introduction This report provides an analysis of the Green Belt surrounding Goldthorpe (Dearne Towns, including Thurnscoe and Bolton on Dearne). -

Dearne Valley Eco-Vision Final Report.Pdf

DEARNE VALLEY ECO-VISION “Perhaps we cannot raise the winds. But each of us can put up a sail, so that when the wind comes we can catch it.” E.F.Schumacher ‘The future of the Dearne Valley will be re-imagined by an eco-vision. The vision is of a place transformed by the know-how of its people and by the imagination and commitment of its communities and enterprises. It will be a place defined by action, in the knowledge that time is running out for the status quo. Within a decade it will be the lowest carbon community of its kind in the country. A pioneer proud to tell its story and share its experiences. Using its distinct resources, assets and potential as a foundation, the Dearne will build a lean, green economy in preparation for the challenges that lie ahead. But above all the eco-vision will rekindle the work ethic of the Dearne’s forefathers, providing a renewed sense of purpose and inspiration for the next generation.’ Published May 009 Sheffield City Region The Source 00 Meadowhall Way Sheffield S9 EA Tel: 0 6 5685 Email: [email protected] Web: www.sheffieldcityregion.org.uk The Dearne Valley eco-vision was commissioned by the Dearne Valley Special Board, one of the Sheffield City Region’s five thematic working groups. The eco-vision was produced by Nick Dodd, Jonathan Brown and John Sampson from URBED, with support from Richard Hindley, Nick Gardner and Joanne Parkin at SQW, and Jonathan Turner and Sarah Bull from DTZ. The authors wish to acknowledge the support of Joanne Wehrle from Rotherham Council, Martin Cantor from Barnsley Council and Stuart Jenkinson from the Environment Agency, as well as members of the Dearne Valley Officers Group and other key consultees (see Chapter 8 for a listing), in developing the eco-vision. -

Church Lane, Harlington, Doncaster, South Yorkshire, DN5 7HZ Asking Price £195,000

15 Church Lane, Harlington, Doncaster, South Yorkshire, DN5 7HZ Asking Price £195,000 This LARGE SEMI DETACHED HOUSE situated in the popular and sought after village of Harlington, which offers the potential of further development. Offering GENEROUS ACCOMODATION over two floors boasting THREE BEDROOMS and a shower room to the first floor, a seperate lounge and dining room, kitchen and hallway to the ground floor. There is also the added benefit of a driveway providing ample off road parking as well as an attached garage with useful w.c. Sold with NO ONWARD CHAIN and immediate vacant possession. Harlington Dining Room 8'5" x 11'8" (2.59 x 3.57) Harlington is a village in the civil parish of Barnburgh in the Metropolitan Borough of Doncaster in South Yorkshire, England. The village lies less than a mile from the adjoining village of Barnburgh and the parish contains both villages. According to the 2001 census, Harlington had a population of 1,979, increasing to 2,297 at the 2011 Census.[1] The village is located about 3 miles (4.8 km) (by road) north of Mexborough, 2 miles (3.2 km) east of Goldthorpe and about 8 miles (13 km) west of Doncaster Entrance Hallway With a rear facing double glazed window and central heating radiator. Kitchen 9'10" x 11'6" (3.02 x 3.51) With a front facing upvc entrance door, central heating Set beneath the rear facing double glazed window and radiator and stairs rising to the first floor incorporated into the roll edge work surface is a drainer accommodation. -

Goldthorpe Masterplan Framework

Goldthorpe Masterplan Framework Version 1.0 JanuaryGoldthorpe 2021 Masterplan Framework 1 Vision GOLDTHORPE To create a deliverable, sustainable, high-quality employment site which will provide for the town and the wider Dearne Valley. The employment site, local plan site reference ES10, is located of the A635 west of Goldthorpe. The Goldthorpe industrial estate is situated to the east and the RSPB Old Moor Wetlands Reserve to the south. RSPB Dearne Valley Old Moor An attractive and high-quality employment-led development will be delivered on the 73 hectare site, comprising of ofces, research and development and industrial uses in Class E. Contents The redevelopment of this site provides an opportunity to deliver a high-quality employment site, whilst What is a Masterplan Framework 3 Design considerations: 12 responding positively to the surrounding environment. and why is it required? Movement and transport By respecting the site and its surroundings, the site Technical considerations 7 The concept masterplan 14 will be set within green infrastructure and will aim to embrace low carbon and energy usage. Site constraints 10 Next steps 18 Site opportunities 11 Goldthorpe Masterplan Framework 2 What is a Masterplan Framework and why is it required? Barnsley National Council’s Local Plan Goldthorpe Planning Planning Policy and Supplementary Masterplan Applications and Guidance Planning Framework Documents Each council is required by government to produce a development plan. The Barnsley Local Plan The Masterplan Framework consultation allows This feedback will be reviewed and considered was adopted by the council in January 2019. residents and stakeholders to be involved and when drawing up the fnal Masterplan Framework. -

Bolton House Farm OCCS, Goldthorpe, South Yorkshire Agricultural Land Classification October 1996 Resource Planning Team ADAS Re

Bolton House Farm OCCS, Goldthorpe, South Yorkshire Agricultural Land Classification October 1996 Resource Planning Team ADAS Reference: 93/96 Leeds Statutory Group MAFF Reference: EL 11084 ADAS Leeds LUPU Commission: N2868 ALCBOL2 DOCW.C5\MT I BOLTON HOUSE FARM, GOLDTHORPE AGRICULTURAL LAND CLASSIFICATION REPORT I I Introduction 1 This report presents the findings of a detailed Agricultural Land Classification (ALC) I survey of 9 2 ha of land at Bolton House Farm The survey was carried out during August 1996 I 2 The survey was commissioned by the Ministry of Agriculture, Fisheries and Food (MAFF) Land Use Planning Unit, Northallerton in connection with a proposal to extract coal by open cast methods Land is not proposed to be restored to agriculture The site was I surveyed in 1993 for the Barnsley UDP (ref DE 19) 3 The work was conducted by members of the Resource Planning Team in the Leeds I Statutory Group in ADAS The land has been graded in accordance with the published MAFF ALC guidelines and criteria (MAFF, 1988) A description of the ALC grades and subgrades is given in Appendix I I 4 At the time of survey the agricultural land on the site was in grassland Parts of the site are in non agricultural use - farm buildings and part of a disused brick works I Summary I 5 The findings of the survey are shown on the enclosed ALC map The map has been drawn at a scale of 1 5,000 It is accurate at this scale but any enlargement would be I misleading 6 The area and proportions of the ALC grades and subgrades on the surveyed land are I summarised -

Town Investment Plan for Goldthorpe

TOWN INVESTMENT PLAN SUMMARY Goldthorpe December 2020 3 Contents Foreword ..................................................................................................................................................... 2 1. Introduction to the Goldthorpe Town Investment Plan .......................................................................... 3 2. Key Challenges ..................................................................................................................................... 4 3. Context Analysis .................................................................................................................................... 7 3.1 Evidence of Need ................................................................................................................................ 7 3.2 Goldthorpe’s strengths, weaknesses, opportunities, and challenges ................................................. 8 3.3 Key Opportunities ............................................................................................................................... 9 4. Strategy .................................................................................................................................................. 12 4.1 The Vision ......................................................................................................................................... 12 4.2 Stakeholder Engagement ................................................................................................................. 13 4.3 Outcomes -

1Dearne South/Dearne Thurnscoe Area Forum

1453 DEARNE NORTH/DEARNE SOUTH AREA FORUM Held at the Dearne High School, Goldthorpe Road, Goldthorpe, Rotherham 10th January 2005 41K (1) Present:- Councillors Thomson (Chairman), Brook, Gardiner, A. Hancock, J. Hancock and Sanderson; together with Mr. G. Horner (Co-opted Member). There were approximately 25 members of the public present. (2) Declarations of Personal Interest There were no declarations of interest of a personal nature from Members. (3) Minutes IT WAS AGREED that the minutes of the Forum held on the 6th December 2004 be taken as read and accepted as a correct record and signed by the Chairman. A member of the public referred to the proposed widening of the footpath in Thurnscoe Road and referred to hedges near a property that were protruding. This had been reported and no action had been taken and they commented upon people in wheelchairs not being able to pass in the area. A Forum Member referred to a recurring problem and they need to inform the owner. They thought that if works were not carried out within a certain period of time that this could be done by the authority who could make a charge for the works. They understood that the owner has been notified. A member of the public stated that they had informed the Area Forum Officer and had been to a Councillors surgery and nothing had been done. A Forum Member stated that the Area Forum Officer will take the matter up and get back to the member of the public concerned. (4) Police and Community Safety PC Jane Morris was present at the meeting and gave an update on the Local Partnership Team’s work. -

Dearne Valley Landscape Partnership Heritage Audit1 123425637895A46b976cc9ccd9e47

ABCCDAEFC EFDFD ABCCCCDE ABCDEFCABCDEF A !"!!# B $ %&$ % $ A '% AA $ A B " ( A )$ % % # * &$ % %"+%B %& ' $% AA'AB $ AA B &",$- $A. # !/%% B ,B&" EBE B!A"##$%A&' 012334D5EE3CC66637'12334D5EE3FC88F 9&""###""" :CDEF !;'%<A +13 #$+E,= >A&<AB&."; "E3FD6DE >&; ?( 4"@D8DAD5- 4"->+3C63A5 B(DDA ()DBEFBA**+++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++F ,C(-BDF.(*DF(+++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++ & FD(BDF(+++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++& ' (BDF(++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++& / *DE(((++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++& F"E AB)%""""""""""""""""""""""""""""""""""""""""""""""""""""""""""""""""""""""""""""""""""""""""""""""""""""""""""""""E F"C -""""""""""""""""""""""""""""""""""""""""""""""""""""""""""""""""""""""""""""""""""""""""""""""""""""""""""""""""""""""""""""""""""C B(**FDDFA++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++' 3"E """"""""""""""""""""""""""""""""""""""""""""""""""""""""""""""""""""""""""""""""""""""""""""""""""""""""""""""""""""""""""""""""""C 3"C (AB# """""""""""""""""""""""""""""""""""""""""""""""""""""""""""""""""""""""""""""""""""""""""""""""""""""""""""""""""""""""""""""F