Predation of a Brown-Throated Three-Toed Sloth (Bradypus Variegatus) in Costa Rica

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Carnivora: Mustelidae: <I>Eira Barbara</I>

Western North American Naturalist Volume 67 Number 1 Article 21 3-27-2007 Noteworthy record of the tayra (Carnivora: Mustelidae: Eira barbara) in the Sierra Gorda Biosphere Reserve, Querétaro, México Carlos A. López González Universidad Autónoma de Querétaro, Querétaro Daniel R. Aceves Lara Universidad Autónoma de Guadalajara, Jalisco Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarsarchive.byu.edu/wnan Recommended Citation López González, Carlos A. and Aceves Lara, Daniel R. (2007) "Noteworthy record of the tayra (Carnivora: Mustelidae: Eira barbara) in the Sierra Gorda Biosphere Reserve, Querétaro, México," Western North American Naturalist: Vol. 67 : No. 1 , Article 21. Available at: https://scholarsarchive.byu.edu/wnan/vol67/iss1/21 This Note is brought to you for free and open access by the Western North American Naturalist Publications at BYU ScholarsArchive. It has been accepted for inclusion in Western North American Naturalist by an authorized editor of BYU ScholarsArchive. For more information, please contact [email protected], [email protected]. Western North American Naturalist 67(1), © 2007, pp. 150–151 NOTEWORTHY RECORD OF THE TAYRA (CARNIVORA: MUSTELIDAE: EIRA BARBARA) IN THE SIERRA GORDA BIOSPHERE RESERVE, QUERÉTARO, MÉXICO Carlos A. López González1 and Daniel R. Aceves Lara2 Key words: tayra, Eira barbara, Querétaro, distribution. The tayra (Eira barbara), a neotropical and Freer 1990). Tayras are reported as rare mustelid belonging to a monotypic genus, is above 1200 m. one of the least studied carnivores in North Mesocarnivore species detected in the local- and Central America. Its distribution includes ity are jaguarondi (Puma yaguoarondi), ocelot South America and Central America. It has (Leopardus pardalis), gray fox (Urocyon cinere- been recorded in southern México in the states oargenteus), and white-nosed coati (Nasua nar- of Chiapas and Oaxaca, and in the north along ica; Lopez Gonzalez unpublished data). -

Notes on the Distribution, Status, and Research Priorities of Little-Known Small Carnivores in Brazil

Notes on the distribution, status, and research priorities of little-known small carnivores in Brazil Tadeu G. de OLIVEIRA Abstract Ten species of small carnivores occur in Brazil, including four procyonids, four mustelids (excluding otters), and two mephitids. On the IUCN Red List of Threatened Species eight are assessed as Least Concern and two as Data Deficient. The state of knowledge of small carnivores is low compared to other carnivores: they are among the least known of all mammals in Brazil. The current delineation of Bassaricyon and Galictis congeners appears suspect and not based on credible information. Research needs include understanding dis- tributions, ecology and significant evolutionary units, with emphasis on theAmazon Weasel Mustela africana. Keywords: Amazon weasel, Data Deficient, Olingo, Crab-eating Raccoon, Hog-nosed Skunk Notas sobre la distribución, estado y prioridades de investigación de los pequeños carnívoros de Brasil Resumen En Brasil ocurren diez especies de pequeños carnívoros, incluyendo cuatro prociónidos, cuatro mustélidos (excluyendo nutrias) y dos mephitidos. De acuerdo a la Lista Roja de Especies Amenazadas de la UICN, ocho especies son evaluadas como de Baja Preocupación (LC) y dos son consideradas Deficientes de Datos (DD). El estado de conocimiento de los pequeños carnívoros es bajo comparado con otros carnívoros y se encuentran entre los mamíferos menos conocidos de Brasil. La delineación congenérica actual de Bassaricyon y Galictis parece sospechosa y no basada en información confiable. Las necesidades de investigación incluyen el entendimiento de las distribuciones, ecología y unidades evolutivas significativas, con énfasis en la ComadrejaAmazónica Mustela africana. Palabras clave: Comadreja Amazónica, Deficiente de Datos, Mapache Cangrejero, Olingo, Zorrillo Introduction 1999), but recently has been recognised (e.g. -

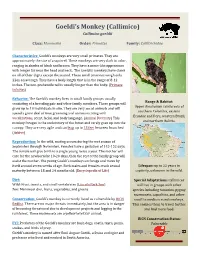

Goeldi's Monkey

Goeldi’s Monkey (Callimico) Callimico goeldii Class: Mammalia Order: Primates Family: Callitrichidae Characteristics: Goeldi’s monkeys are very small primates. They are approximately the size of a squirrel. These monkeys are very dark in color, ranging in shades of black and brown. They have a mane-like appearance with longer fur near the head and neck. The Goeldi’s monkeys have claws on all of their digits except the second. These small primates weigh only 22oz on average. They have a body length that is in the range of 8-12 inches. The non-prehensile tail is usually longer than the body. (Primate Info Net) Behavior: The Goeldi’s monkey lives in small family groups usually consisting of a breeding pair and other family members. These groups will Range & Habitat: Upper Amazonian rainforests of grow up to 10 individuals in size. They are very social animals and will southern Colombia, eastern spend a great deal of time grooming and communicating with Ecuador and Peru, western Brazil, vocalizations, scent, facial, and body language. (Animal Diversity) This and northern Bolivia. monkey forages in the understory of the forest and rarely goes up into the canopy. They are very agile and can leap up to 13 feet between branches! (Arkive) Reproduction: In the wild, mating occurs during the wet season of September through November. Females have a gestation of 145-152 days. The female will give birth to a single young twice a year. The mother will care for the newborn for 10-20 days, then the rest of the family group will assist the mother. -

Effects of Human Presence on Mammal Populations

Tropical Ecology and Conservation in Costa Rica UW students have the opportunity to study abroad on the CIEE Tropical Ecology and Conservation program in Monteverde, Costa Rica. The following is a presentation on Anne Vandenburg’s independent research project during her term abroad. Anne is a Zoology and Spanish major with a certificate in Environmental Studies. She received the Study Abroad Scholars to support her studies in Costa Rica. Effects of Human Presence on Mammal Populations Independent research project conducted for Tropical Ecology and Conservation program in Monteverde, Costa Rica Choosing a Project • General area of interest: – Mammals – How are humans impacting environment? – Costs vs. benefits of ecotourism • Topic: How does ecotourism in the Monteverde Cloud Forest Reserve affect the mammal populations living there? • Create experimental design with help of research advisor Research Site: Monteverde Cloud Forest Reserve • Very high tourist traffic • Benefits of tourism to the Reserve: – Good for local economy • Employees of the Reserve • Tourism brings money to hotels & restaurants • Most Monteverde residents employed directly or indirectly by ecotourism business – Environmental protection • Very small section of the reserve open to tourism • All profit from entrance fees used for conservation Experimental Procedure • Trail 1: heavy tourist traffic • Trail 2: restricted; reserve staff and pre-approved researchers only (used very rarely) • Data collected on 5 trail cameras per trail, spaced every .25km, left for 2 weeks -

Papallacta, San Isidro & Wild Sumaco, 2019

Ecuador, September 2019 Michael Kessler In September 2019 I attended a conference in Quito, Ecuador. I spent 6 days prior to the conference vising some sites that I did not yet know, looking for birds and mammals. Mammal- wise, my main targets were Mountain Tapir and Dusky Shrew-Opossum, which would be a new family for me. Both were found, as was my 1000th mammal species, which due to some creative accounting ended up being a monkey rather than a rodent . Itinerary 10.09.: Arrival in Quito at 13:30, rent car and drive to San Isidro (4 hours due to stops at landslides). 11.09.: Full day at San Isidro, with night walks from 3:00 to dawn and for a few hours after dinner. Strong rain later at night precluded further walks. 12:09.: Drive to Wild Sumaco. Heavy rain until 16:00. Six hours night walks around the lodge. 13.09.: Most of the day in the forest; started raining in the evening again, so little night work. 14.09.: Drive to Guango Lodge, with a 7 hour wait due to a landslide in Cordillera Guacamayos. Night walk above Papallacta, followed by night walk in Guango. 15.09.: Predawn walk at Guango, started raining again at 7:00, so that the planned visit to Cayambe-Coca did not work out. Drove on to Quito. 18.9.: Botanical day trip to Cayambe Coca NP with participants of the conference, with 4 mammal species recorded on the side. The lodges are all well known, so I only give some updates. -

Emas NP – Brazil

Emas NP – Brazil 31 july – 05 August 2019 Introduction I visited Emas NP in Brazil as a part of a bigger South America trip mainly for the chance of Pampas cat and Maned wolf. I am not a fan of baited animals so Caraca´s sanctuary and their famous church was out of question for Maned wolf for me. I wanted to see them in their right environment. Real stuff. I was really hoping for some daytime sightings of them as well and Emas NP seemed like the right place for me. An odd chance of Pampas cat didn´t make my decision very hard. I stayed 5 nights in the lovely Pousada Do Gloria https://pousadadogloria.wixsite.com/parquenacionalemas I can´t recommend this place high enough. Such a friendly place and with direct proximity to the park itself. Very nice food and also a bunch of wildlife just outside your door. I did all of my drives inside the park. In general between 06:00 - 12:00 and 15:30 – 20:30 The pousada has their own “safari car” which I used solely with my driver and guide Ana who is also manager of the Pousada. She is a very good guide and have been in this park for 10 years. She knows it better than anyone else. Pousada Do Gloria doesn´t look much from the outside but it´s a lovely place. One of the places in the world you are truly missing when you leave. Clean, fresh rooms, WiFi and all the comfort you need. -

2017-Predator Prey Activity Budgets

Determining the Significance of Relative Abundance in Overlap of Predator-Prey Activity Budgets for Mammalian Species in the Cloud Forests of Costa Rica Ellen Asselin Mentor: Michael Mooring Committee: Ryan Botts, Heidi Woelbern ABSTRACT. – A rudimentary knowledge of the relationships between organisms in an ecosystem is important for the monitoring and conservation of an ecosystem. Predator-prey relationships can provide insight into the fluctuation of specific populations, and inequalities in predator-prey populations can explain unnatural behaviors such as predation upon livestock by a predator that no longer has access to a sufficient abundance of its preferred prey species (Burgas et al., 2014). These relationships have frequently been determined via direct observation and dietary analysis from fecal sampling. Morphological and DNA analysis of fecal samples, while potentially challenging to identify to the species level, can provide valuable information about the dietary habits of predators by indicating which prey species’ DNA is found in predator’s feces. In the tropical montane forests of Costa Rica’s Talamanca mountain range, however, these methods are unrealistic options to gain an understanding of the basic network of predator- prey relationships. The Cordillera de Talamanca is a characteristic mountain region that separates the Atlantic coast from the Pacific coast from central Costa Rica to northern Panama- its rugged terrain has impeded direct survey efforts of medium to large mammals. The mammals in this range are seldom witnessed due to their elusive nature, and high rainfall and tropical temperatures lead to rapid detritus turnover, making fecal sample collection difficult (Tobler et al., 2006). The cloud forests of the Talamanca Cordillera are home to numerous subsistence ranchers, whose livestock’s wellbeing is contingent upon adequate prey populations for such large carnivorous felines such as the jaguar Panthera onca and puma Puma concolor, keystone predators who are capable of livestock predation (Burgas et al., 2014). -

Eira Barbara) in Southern Mexico

Western North American Naturalist Volume 77 Number 3 Article 12 9-29-2017 Range expansion of a locally endangered mustelid (Eira barbara) in southern Mexico Fernando Ruiz-Gutiérrez Universidad Autónoma de Guerrero, Av. Lázaro Cárdenas S/N Col. La Haciendita, Ciudad Universitaria, Chilpancingo, Guerrero, México, [email protected] Enrique Vázquez-Arroyo Universidad Autónoma de Guerrero, Av. Lázaro Cárdenas S/N Col. La Haciendita, Ciudad Universitaria, Chilpancingo, Guerrero, México, [email protected] Cuauhtémoc Chávez Universidad Autonoma Metropolitana Lerma de Villado, Estado de México, México, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarsarchive.byu.edu/wnan Recommended Citation Ruiz-Gutiérrez, Fernando; Vázquez-Arroyo, Enrique; and Chávez, Cuauhtémoc (2017) "Range expansion of a locally endangered mustelid (Eira barbara) in southern Mexico," Western North American Naturalist: Vol. 77 : No. 3 , Article 12. Available at: https://scholarsarchive.byu.edu/wnan/vol77/iss3/12 This Note is brought to you for free and open access by the Western North American Naturalist Publications at BYU ScholarsArchive. It has been accepted for inclusion in Western North American Naturalist by an authorized editor of BYU ScholarsArchive. For more information, please contact [email protected], [email protected]. Western North American Naturalist 77(3), © 2017, pp. 408–413 RANGE EXPANSION OF A LOCALLY ENDANGERED MUSTELID (EIRA BARBARA) IN SOUTHERN MEXICO Fernando Ruiz-Gutiérrez1, Enrique Vázquez-Arroyo1, and Cuauhtémoc Chávez2 ABSTRACT.—We documented the occurrence of Eira barbara in the municipalities of Tecpán de Galeana and Petatlán, state of Guerrero, Mexico. Our records represent a 450-km range expansion from the most recent northern occurrences of this species in the Mexican Pacific coast states. -

Advice to Applicants on Licence Conditions Revised July 2014 2

The Dangerous Wild Animals Act 1976 Advice to Applicants on Licence Conditions Revised July 2014 2 Dangerous Wild Animal Licences are administered by the Council’s Licensing Team. Officers may be contacted on 01507 601111 ext 3488 or by email at [email protected] This advice booklet is issued by: The Licensing Team, East Lindsey District Council, Tedder Hall, Manby Park, Louth, Lincolnshire LN11 8UP If you would like this information in another language, large print or Braille, please contact us on 01507 601111. 3 Contents General Information for Applicants ..............................................................4 Section 1 Conditions attached to your licence ...................................7 Section 2 Conditions which must be satisfied before a licence is granted ....................................................8 Section 3 Considerations you should make ...................................... 10 Section 4 Animals that require a Dangerous Wild Animals Act Licence ................................................... 12 Section 5 Insurance ................................................................................. 21 Section 6 Staff safety / Public safety ................................................. 22 Section 7 Emergencies and fire precautions .................................... 23 4 Dangerous Wild Animals Act Licences General Information For Applicants 1. Licences are given for a maximum period of 24 months. 2. Applicants are advised that the law requires the Council to arrange for the inspection of the premises by a Veterinary Surgeon or a Veterinary Practitioner. The fee for this service is additional to the standard licence fee and will initially be invoiced by the vet to the Council, who will pay this and recharge it to the applicant. You are welcome to request that the premises are inspected by the vet you normally use for treatment of your animals. If you do not wish to do this, the Council will appoint an appropriate Veterinary Surgeon or Practitioner as it sees fit. -

1 Finding and Conserving the Little Spotted Cat of Yungas, Argentina

1 Finding and conserving the little spotted cat of Yungas, Argentina Project ID: 0615010 Host country: Argentina. Study site: Acambuco Provincial Reserve (Salta Province), Lotes 50-51 Provincial Reserve and PanAmerican Energy Properties. Field surveys: 18-jun-11 to 21-sep-11; 15- nov-11 to 03-mar-12 Organizations: CETAS, CONICET. The overall aim: Generate distribution and ecological information and to raise awareness for the conservation of Oncilla ( Leopardus tigrinus ). Griet An Erica Cuyckens Correspondence: CETAS - Ecología de Comunidades, Facultad de Ciencias Agrarias, Alberdi 47, 4600 San Salvador de Jujuy, Argentina e-mail: [email protected] http://centroestudiosterrit.wix.com/cetas 2 Table of Contents Table of Contents ........................................................................................................................... 2 Acknowledgements ........................................................................................................................ 4 Section 1: ....................................................................................................................................... 5 Summary .................................................................................................................................... 5 Introduction ............................................................................................................................... 5 Project members ....................................................................................................................... -

List of 28 Orders, 129 Families, 598 Genera and 1121 Species in Mammal Images Library 31 December 2013

What the American Society of Mammalogists has in the images library LIST OF 28 ORDERS, 129 FAMILIES, 598 GENERA AND 1121 SPECIES IN MAMMAL IMAGES LIBRARY 31 DECEMBER 2013 AFROSORICIDA (5 genera, 5 species) – golden moles and tenrecs CHRYSOCHLORIDAE - golden moles Chrysospalax villosus - Rough-haired Golden Mole TENRECIDAE - tenrecs 1. Echinops telfairi - Lesser Hedgehog Tenrec 2. Hemicentetes semispinosus – Lowland Streaked Tenrec 3. Microgale dobsoni - Dobson’s Shrew Tenrec 4. Tenrec ecaudatus – Tailless Tenrec ARTIODACTYLA (83 genera, 142 species) – paraxonic (mostly even-toed) ungulates ANTILOCAPRIDAE - pronghorns Antilocapra americana - Pronghorn BOVIDAE (46 genera) - cattle, sheep, goats, and antelopes 1. Addax nasomaculatus - Addax 2. Aepyceros melampus - Impala 3. Alcelaphus buselaphus - Hartebeest 4. Alcelaphus caama – Red Hartebeest 5. Ammotragus lervia - Barbary Sheep 6. Antidorcas marsupialis - Springbok 7. Antilope cervicapra – Blackbuck 8. Beatragus hunter – Hunter’s Hartebeest 9. Bison bison - American Bison 10. Bison bonasus - European Bison 11. Bos frontalis - Gaur 12. Bos javanicus - Banteng 13. Bos taurus -Auroch 14. Boselaphus tragocamelus - Nilgai 15. Bubalus bubalis - Water Buffalo 16. Bubalus depressicornis - Anoa 17. Bubalus quarlesi - Mountain Anoa 18. Budorcas taxicolor - Takin 19. Capra caucasica - Tur 20. Capra falconeri - Markhor 21. Capra hircus - Goat 22. Capra nubiana – Nubian Ibex 23. Capra pyrenaica – Spanish Ibex 24. Capricornis crispus – Japanese Serow 25. Cephalophus jentinki - Jentink's Duiker 26. Cephalophus natalensis – Red Duiker 1 What the American Society of Mammalogists has in the images library 27. Cephalophus niger – Black Duiker 28. Cephalophus rufilatus – Red-flanked Duiker 29. Cephalophus silvicultor - Yellow-backed Duiker 30. Cephalophus zebra - Zebra Duiker 31. Connochaetes gnou - Black Wildebeest 32. Connochaetes taurinus - Blue Wildebeest 33. Damaliscus korrigum – Topi 34. -

Monkey Sanctuary

Monkey Sanctuary This centre is located in an isolated area of the Ecuadorian rainforest. The centre was established in 2006 and works in rescuing, rehabilitating and when possible releasing animals back to their natural environment. The centre works in partnership with the Ecuadorian Environmental Police (UPMA) and the Ministry of Environment in the fight against trafficking, abuse, capture and hunting of wild animals. Animal welfare is not often a high priority for many Ecuadorians and many do not understand the problems associated with keeping wild animals as domestic pets as they often become depressed/aggressive and as a result are neglected and abused and many of the animals arriving at the centre have been mistreated with either physical and/or psychological injuries. The rescue centre covers an area of over 100 hectares on the land of the Alvarez Guatactuca family. This is a Quichua family whose ancestral line over this land and area stems back hundreds of years. As a family-run rescue centre, they have a great understanding of the local community, their culture and the plight of their native wild animals. What started as a small centre for monkeys has expanded to a centre that at the request of the Government now takes in all types of wild animals. This is a great opportunity to work not only with monkeys but with a variety of exotic animals. There are currently over 60 animals at the centre which include: primates (squirrel, titi and capuchin monkeys) mammals (peccaries, coati, tayra, kinkajou, margay), reptiles (tortoises) and birds (turkey, parrots and macaws).