SOCIAL RESPONSIBILITY in the Smmes of the BOTSHABELO INDUSTRIAL ESTATES

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Provincial Gazette Provinsiale Koerant

Provincial Provinsiale Gazette Koerant Free State Province Provinsie Vrystaat Published by Authority Uitgegee op Gesag NO.87 FRIDAY, 29 NOVEMBER 2019 NR.87 VRYDAG, 29 NOVEMBER 2019 PROVINCIAL NOTICES PROVINSIALE KENNISGEWINGS 94 Roads Notice 94 Paaiekennisgewing (P35/2/8) Declaration of a public road………..…….. 3 (P35/2/8): Verklaring van ‘n openbare pad………… 3 95 Roads Notice 95 Paaiekennisgewing Commission of Inquiry Kommissie van Ondersoek (P37/2/173)……………………………………………. 4 (P37/2/173)………………………………………………… 4 GENERAL NOTICES ALGEMENE KENNISGEWINGS 153 Mangaung Municipality Land Use Planning By-Law 153 Mangaung Munisipale Grondgebruikbeplanning- (Provincial Gazette Number 35 of 30 July 2015): Regulasie (Provinsiale Gazette Nommer 35 van 30 a. Universitas: Erf 8717, Ex 55, district Julie 2015): Bloemfontein. a. Universitas: Erf 8717, Uittbreiding 55, distrik b. Universitas: Erf 8718, Ex 55, district Bloemfontein Bloemfontein. b. Universitas: Erf 8718, Uitbreiding 55, distrik c. Universitas: Erf 8754, Ex 55, district Bloemfontein. Bloemfontein. c. Universitas: Erf 8754, Uitbreiding 55, distrik d. Universitas: Erf 8906, Ex 55, district Bloemfontein. Bloemfontein d. Universitas: Erf 8906, Uitbreiding 55, distrik e. Universitas: Remainder of Erf 8733, Ex 55, Bloemfontein district Bloemfontein………………………………. 4 e. Universitas: Restant van Erf 8733, Uitbreiding 55, distrik Bloemfontein…………………………………. 4 154 Removal of Restrictive Title Deed Conditions, Opheffing van Beperkende Voorwaardes, Wysigings 154 Amendment of the Bloemfontein Town Planning van die Bloemfontein Dorpsaanlegskema en Scheme and Rezoning: Erf 8461, Universitas, Hersonering: 8461, Universitas, Bloemfontein…….…... 6 Bloemfontein………………………………………….... 6 MISCELLANEOUS ALGEMEEN Notice of Nominations for Members of Hospital Boards: Invitation to Nominate Members to Serve on Hospital Boards - Free State Province…………………………………………………. 7 Department of Police Roads and Transport: Applications for Public Road Carrier Permits: Advert 272….…. -

Provincial Gazette Provinsiale Koerant

Provincial Provinsiale Gazette Koerant Free State Province Provinsie Vrystaat Published byAuthority Uitgegee opGesag No. 79 FRIDAY, 03 OCTOBER 2008 No. 79 VRYDAG, 03 OKTOBER 2008 No. Index Page No. Inhoud Bladsy PROCLAMATIONS PROKLAMASIES 48 Declaration of Township: Helicon Heights: 48 Dorpsverklaring: Helicon Hoogte: Extension 7 ,................................................... 2 Uitbreiding 7 2 49 Amendment of the Town-Planning Scheme of 49 Wysiging van die Dorpsaanlegskema van Clarens , , 3 Clarens ,................................. 3 PF10VINCIAL NOTICES PROVINSIALE KENNISGEWINGS 330 Removal of Restrictions Act, 1967 (Act No. 84of 1967): 330 Wet opOpheffing van Beperkings, 1967 (Wet No. 84van Langenhoven Park: Erf924 6 1967): Langenhovenpark: Erf924 ,..,........ 6 331 Removal of Restrictions Act, 1967 (ActNo. 84of 1967): 331 Wet opOpheffing van Beperkings, 1967 (Wet No. 84van Bloemfontein (Extension 32): (Oranjesig) 6 1967): Bloemfontein (Uitbreiding 32): (Oranjesig) 6 332 Removal of Restrictions Act, 1967 (ActNo. 84of 1967): 332 Wet opOpheffing van Beperkings, 1967 (Wet No. 84 van Bloemfontein: Erf2050 (Waverley) .....,.................... 7 1967): Bloemfontein: Erf 2050 (Waverley) 7 333 Removal of Restrictions Act, 1967 (Act No. 84of 1967) 333 Wet opOpheffing van Beperkings, 1967 (Wet No. 84van Bloemfontein: Erf7103 (Wilgehof) 7 1967): Bloemfontein: Erf7103 (Wilgehof) 7 334 Removal of Restrictions Act, 1967 (Act No. 84of 1967): 334 Wet opOpheffing van Beperkings, 1967 (Wet No. 84 van Clarens 8 1967): Clarens 8 335 Removal of Restrictions Act, 1967 (Act No. 84of 1967): 335 Wet opOpheffing van Beperkings, 1967 (Wet No. 84 van Bloemfontein: Erf533 (Arboretum) ...,. ..,......,......... 8 1967): Bloemfontein: Erf533(Arboretum) ,., ,.,.. 8 336 Removal of Restrictions Act, 1967 (Act No. 84of 1967): 336 Wet opOpheffing van Beperkings, 1967 (Wet No. 84van Sasolburg '......'..................................................... 8 1967): Sasolburg ,., ,.., ,....... -

The Role of Sustainable Planning in Order to Accommodate Informal Brickyards in the Integrated Development Plan of the Mangaung Municipality

G.M. Steenkamp & J.J. Steÿn, Int. J. Sus. Dev. Plann. Vol. 1, No. 4 (2006) 443–450 TO CONTROL OR NOT TO CONTROL: THE ROLE OF SUSTAINABLE PLANNING IN ORDER TO ACCOMMODATE INFORMAL BRICKYARDS IN THE INTEGRATED DEVELOPMENT PLAN OF THE MANGAUNG MUNICIPALITY G.M. STEENKAMP & J.J. STEŸN Department of Urban and Regional Planning, University of the Free State, Bloemfontein, South Africa. ABSTRACT During 1994 and 1999, the Bloemfontein Municipality amalgamated with five other municipalities to form the Mangaung Municipality. The Mangaung Municipality now has a population of approximately 740,000 and covers an area of 6,363 km2. Some areas are totally urban; while in others, people live in informal settlements. The unemployment rate is 35%, but in some areas it has risen to as high as 48%. Poor people in the city cannot afford to buy burnt bricks from the major suppliers of bricks. Therefore, informal brickyards were established all over the areas where clay and/or water were available. These brickyards are now producing good homemade burnt bricks and are creating jobs in a sea of unemployment. However, the problem is that from a planning and sustainability viewpoint, all is not well.Although the location of the brickyards has brought about a saving in costs related to the transportation of bricks from the formal brickyards, of which the nearest is 300 km away, the coal- burning activities of the informal brickyards create air pollution. Furthermore, no prior environmental impact studies were carried out before deciding on the location of the brickyards. Most of them have been established haphazardly in any available spot. -

Freestate Presentation

PortfolioPortfolio CommitteeCommittee MeetingMeeting Free State 2 March 2010 Provincial Commissioner Mashigo Demographics Population figure 2 902 400 Number of stations Present total 109 RAG vs Real resources - Human Resources Granted Actual SA Police Act 8 415 8 539 Public Service Act 2 421 2 260 Total 10 836 10 799 - 37 Difference (0.34% not yet filled) Students @ Stations (excl Students @ Colleges) 758 RAG vs Real resources – Vehicles Personnel number Actual Vehicles 10 799 2 720 Vehicle ratio 1:3,9 Other essential resources Bulletproof Firearms Vests 13 196 12 164 High1 Aprilcrime 2009 areas – 31 January - Contact 2010 REPORTED CRIMES TOP 10 CONTRIBUTORS • Assault Common • Parkweg • Assualt GBH • Thabong • Rape • Bloemspruit • Common Robbery • Sasolburg • Robbery Aggravating • Kagsanong • Robbery with weapon other than • Bethlehem firearm • Botshabelo • Murder • Welkom • Attempted Murder • Boithuso • Sexual Assault • Mangaung • Attempted Robbery: Aggravated: with firearm • Attempted Common Robbery *Stations listed has the highest *Crimes listed from the most to the reported figure least reported Station performance High Contact Crime stations TOP 3 PERFORMERS BOTTOM 3 PERFORMERS • Batho • Bloemspruit • Botshabelo • Kagisanong • Odendaalsrus • Parkweg Large Stations TOP 4 PERFORMERS BOTTOM 4 PERFORMERS • Virginia • Mangaung • Kroonstad • Bloemspruit • Batho • Kagisanong • Ficksburg • Parkweg Station performance Medium and Small stations TOP 10 PERFORMERS BOTTOM 10 PERFORMERS • Reitz • Heidedal • Allanridge • Soutpan • Koppies • Kopanong -

Provincial Gazette Provinsiale Koerant

Provincial Provinsiale Gazette Koerant Free State Province Provinsie Vrystaat Published by Authority Uitgegee op Gesag NO. 19 FRIDAY, 31 JULY 2020 NR.19 VRYDAG, 31 JULIE 2020 PROVINCIAL NOTICES PROVINSIALE KENNISGEWINGS 20 Moqhaka Municipality: 20 Moqhaka Munisipaliteit: Property Rates………………………………………… 3 Eiendomsbelasting………………………………………… 3 21 Dihlabeng Local Municipality Resolution Levying Property Rates for the Financial Year 1 July 2020 to 30 June 2021…..………………. 5 GENERAL NOTICES ALGEMENE KENNISGEWINGS 26 Notice: Erf 1/336, Ficksburg - application for 26 Kennisgewing: Erf 1/336, Ficksburg - aansoek vir rezoning………………………………………………. 5 hersonering………………………………………………… 5 27 Spatial Planning and Land Use Management Act, 27 Wet op Ruimtelike Beplanning en Grondgebruik- 2013 (Act No. 16 of 2013): bestuur, 2013 (Wet No. 16 Van 2013): a) Erf 40516, Hillside, Extension 181, a) Erf 40516, Hillside, Extension 181, b) Erf 21422, Waverley, Bloemfontein b) Erf 21422, Waverley, Bloemfontein c) Erf 2571, Westdene, Bloemfontein c) Erf 2571, Westdene, Bloemfontein d) Portion 7 of Erf 1823, Waverley, Bloemfontein d) Gedeelte 7 van Erf 1823, Waverley, Bloemfontein e) Erf 6372, Dan Pienaar, Bloemfontein e) Erf 6372, Dan Pienaar, Bloemfontein f) Erf 30375, Bloemfontein Extension 213, Wild f) Erf 30375, Bloemfontein Erf 213, Wild Olive Olive Estate, Bloemfontein Estate, Bloemfontein g) Erf 30235, Bloemfontein Extension 231, Wild g) Erf 30235, Bloemfontein Erf 231, Wild Olive Olive Estate, Bloemfontein …………………….. 6 Estate, Bloemfontein ………………………………… 6 28 A. Amendment of Bloemspruit Town Planning 28 A. Wysiging van Bloemspruit Dorpaanlegskema Nr. 1 Scheme No. 1 of 1984 by inclusion of the new van 1984 deur ’n nuwe sonering “Spesiale Gebruik zoning “Special Use 37” 37” by te voeg. B. Removal of restrictive title deed conditions on B. -

Built Environment Performance Plan for Mangaung Metro

BUILT ENVIRONMENT PERFORMANCE PLAN FOR MANGAUNG METRO (URBAN SETTLEMENT DEVELOPMENT GRANT) MOEKETSI MACHOGO, GM: PLANNING 1 July 2011 Presentation Outline • Introduction and Background • Spatial Development Perspectives • Infrastructure Programmes • Housing Demand • Outcome 8 targets in the Free State Province • Strategic Land Parcels • Overall Transport Plan • Identified Risks and Challenges • USDG Budget allocation per Category Introduction and Background Location of Mangaung (District context) THABA NCHU CITY OF BLOEMFONTEIN BOTSHABELO Mangaung 6 604 square kms Mangaung Metro Context Population Size, 2007 Population Distribution, 2007 % 2001 2007 6% 14% Increase Bloemfontein Population 645 440 752 906 16.65% Botshabelo 52% Thaba Nchu 28% Rural Households 188 876 202 762 7.35% Spatial Development Perspectives Integration Issues and Concepts Spatial fragmentation and interdependent development Spatial integration for sustainability patterns CBD decline, undermining core asset of municipality Strengthening the city core Growth in south eastern and north Intensification, densification and infill western areas are pulling the city apart Consolidate, contain and maintain the towns Distant urban dependency of Botshabelo and Thaba Nchu on Bloemfontein Regional transport efficiency Imbalanced linkages between urban areas and distant rural dependents and neighbours Rural market town Infrastructure Programmes Introduction MMM and more particular IS provides services in different types, levels and categories as follows: • Types of Services: Like -

FREE STATE DEPARTMENT of EDUCATION Address List: ABET Centres District: XHARIEP

FREE STATE DEPARTMENT OF EDUCATION Address List: ABET Centres District: XHARIEP Name of centre EMIS Category Hosting School Postal address Physical address Telephone Telephone number code number BA-AGI FS035000 PALC IKANYEGENG PO BOX 40 JACOBSDAL 8710 123 SEDITI STRE RATANANG JACOBSDAL 8710 053 5910112 GOLDEN FOUNTAIN FS018001 PALC ORANGE KRAG PRIMARY PO BOX 29 XHARIEP DAM 9922 ORANJEKRAG HYDROPARK LOCAT XHARIEP 9922 051-754 DAM IPOPENG FS029000 PALC BOARAMELO PO BOX 31 JAGERSFONTEIN 9974 965 ITUMELENG L JAGERSFORNTEIN 9974 051 7240304 KGOTHALLETSO FS026000 PALC ZASTRON PUBLIC PO BOX 115 ZASTRON 9950 447 MATLAKENG S MATLAKENG ZASTRPM 9950 051 6731394 LESEDI LA SETJABA FS020000 PALC EDENBURG PO BOX 54 EDENBURG 9908 1044 VELEKO STR HARASEBEI 9908 051 7431394 LETSHA LA FS112000 PALC TSHWARAGANANG PO BOX 56 FAURESMITH 9978 142 IPOPENG FAURESMITH 9978 051 7230197 TSHWARAGANANG MADIKGETLA FS023000 PALC MADIKGETLA PO BOX 85 TROMPSBURG 9913 392 BOYSEN STRE MADIKGETLA TROMPSBU 9913 051 7130300 RG MASIFUNDE FS128000 PALC P/BAG X1007 MASIFUNDE 9750 GOEDEMOED CORRE ALIWAL NORTH 9750 0 MATOPORONG FS024000 PALC ITEMELENG PO BOX 93 REDDERSBURG 9904 821 LESEDI STRE MATOPORONG 9904 051 5530726 MOFULATSHEPE FS021000 PALC MOFULATSHEPE PO BOX 237 SMITHFIELD 9966 474 JOHNS STREE MOFULATHEPE 9966 051 6831140 MPUMALANGA FS018000 PALC PHILIPPOLIS PO BOX 87 PHILIPPOLIS 9970 184 SCHOOL STRE PODING TSE ROLO PHILIPPOLIS 9970 051 7730220 REPHOLOHILE FS019000 PALC WONGALETHU PO BOX 211 BETHULIE 9992 JIM FOUCHE STR LEPHOI BETHULIE 9992 051 7630685 RETSWELELENG FS033000 PALC INOSENG PO BOX 216 PETRUSBURG 9932 NO 2 BOIKETLO BOIKETLO PETRUSBUR 9932 053 5740334 G THUTONG FS115000 PALC LUCKHOFF PO BOX 141 LUCKHOFF 9982 PHIL SAUNDERS A TEISVILLE LUCKHOFF 9982 053 2060115 TSIBOGANG FS030000 PALC LERETLHABETSE PO BOX 13 KOFFIEFONTEIN 9986 831 LEFAFA STRE DITLHAKE 9986 053 2050173 UBUNTU FS035001 PALS SAUNDERSHOOGTE P.O. -

£¤N6 £¤N1 £¤N8 £¤N1 £¤N8 £¤N8

WARD DELIMITATION 2021 Mangaung Metropolitan Municipality (MAN) WAR D : 27 22630238 109 R30 Ward 9 DRAFT WARDS ST 22630148 22190015 76 Ward 2 994 Bofulo Kgalala 22120232 22120074 139 22080013 N1 ¤£ Ward 3 239 245 22080046 22630272 Modutung 236 Municipal Demarcation Board Ward 44 115 Tel: (012) 342 2481 22120063 Fax: (012) 342 2480 email: [email protected] 272 web: www.demarcation.org.za 22080057 Ward 27 Morago 613 22120210 Houtnek Kenilworth AH 254 Ü Spitskop Village 21861873 M30 The ST 22120052 745 Kloof Ward 48 R700 21860276 Ward 17 216 RaytonST M30 22120119 Legend Rooidam SH ST 1557 Middeldeel Knocknacree SHLilyvale SH Deals Gift AH 223 R64 Heliconhoogte Olive Hill SH ST Hillsboro Deales Gift Mockes Dam Pentagon Park Bloemfontein Airport Spitshop SH Heuwelsig Bayswater 22120209 Local Municipalities Kiepersol Merino Ratabane Spitskop Noordhoek 213 Tempe Dan Waverley Ward 47 22120186 Paradys Brandwag Pienaar Naval Hill Estoire AH Bloemspruit 141 Wards M14 Bob ST Park WestWestdene Arboretum Airforce Base Bloemfontein Central Hilton Rodgers Park Feloane Kwaggafontein Oos Einde 22080248 22080080 Tiger River Ward 41 Universitas ¤£N8 21861895 22120333 Voting Districts Wilgehof 21860984 797 300 252 22120197 Oranjesig 474 22120108 Gardenia Willows 1384 Bloemdustria N8 Langenhovenpark White City Potsane 220 253 National Roads ¤£ Park Hospitalpark NONE Heidedal Bochabela Kwaggafontein General Opkoms North Shannon SH SH Fichardt Park M30 Main Roads De Wet ST Batho Joe Bloemside Phase 1 Pellissier Fleurdal Peter PPehtaerh aSmweanrtg PhaSsleo -

Mangaung Metropolitan Municipality IPTN Portfolio Committee on Transport

Mangaung Metropolitan Municipality IPTN Portfolio Committee on Transport Implementation of The Bus Rapid Transport Systems 12-13 September 2017 Executive Mayor Cllr SM Mlamleli 2 Outline • Project Overview • Financial Status • Master Programme and Progress Status Update • Risk Management • Aspects of Project well executed/improved in future phases • Challenges faced • Contribution of the project towards: – A single public transport ticketing system, – Implementation of universal access, and, – Smooth inter-operability with other modes. • The Future of BRT 3 Project Overview and Financial Status 4 Project Overview • Project Status - Not operational yet, • “Go Live” during 2019/20 financial year 5 SYSTEM OVERVIEW 6 Mangaung Metropolitan Municipality • Total Population(2015) - 833,141 (MMM Land Use Model 2015); • Total Number of Person Trips in the morning peak period in Metro (2013) – 190 000 (National Household Travel Survey 2013); • Know as walking city – 17% of work related trips, walk all the way to work. (National Household Travel Survey 2013) 7 Full Network Implementation Phasing Phasing - 25 Years BloemfonteinBloemfontein Botshabelo/Thaba Nchu Thaba Nchu Langenhoven 5 5 Park 4 4 3 1 3 Waaihoek 8 6 7 2 • Existing subsidised 4 services Heidedal • NMT implementation 1 Botshabelo part of Phase 1 Lourierpark Implementation Rocklands • Total number of passengers in system and km routes to be finalised with adoption of final IPTN document end 2017 • Subjected to completion of HTS and PT on-board surveys 8 Phase 1 and 2 Patronage and Fleet -

Provincial Gazette for Free State No 43 of 01-August-2014

Provincial Provinsiale Gazette Koerant Free State Province Provinsie Vrystaat Published by Authority Uitgegee op Gesag SPECIAL NO. 43 FRIDAY 01 AUGUST 2014 NO. 43 VRYDAG, 01 AUGUSTUS 2014 PROVINCIAL NOTICE 65 Mangaung Metro Municipality: Bucket Eradication ………………. 2 PROVINCIAL GAZETTE / PROVINSIALE KOERANT, 01 AUGUST 2014 / 01 AUGUSTUS 2014 2 ________________________________________________________________________________________________________ PROVINCIAL NOTICE ------------- [NO. 65 OF 2014] In terms of the Division of Revenue Act, Act No 2 of 2013 Section 29(2) for the 2013/2014 financial year and the Public Finance Management Act, 1999 Section 38(1) (l-n), the Provincial Treasury hereby publishes the information set out in Schedule 1 that relates to the allocation of the amounts as stated in Schedule 2 relating to the allocation of funds from the Provincial Revenue Fund by the Accounting Officer of the Department of Human Settlement to the Mangaung Metropolitan Municipality. SCHEDULE 1 MANGAUNG METRO MUNICIPALITY: BUCKET ERADICATION 1. Transferring Provincial Department Department of Human Settlements 2. Purpose To enable the Mangaung Metro Municipality to implement the bucket eradication projects as well as basic water reticulation for earmarked and prioritized erven in Bloemfontein, Botshabelo and Thaba Nchu. 3. Measurable Outputs Number of sites to be serviced: 3774 4. Conditions The funds for bucket eradication in prioritized areas in Bloemfontein, Botshabelo and Thaba Nchu to be utilized solely and strictly for this purpose. The Mangaung Metro Municipality must make use of registered professional service providers within the boundaries of the Free State as a first priority (though the idea is noble, some of these matters are influenced by the capacity Grading levels required by the Project). -

Motheo Address List 10 September 2018.Pdf

MOTHEO Section 21 Language 2018 Medium Quintile Educators Educators Hostel Status Learners (SGB incl) (SGB EMIS Nr. Name of school Type Category Postal Address Telephone Physical Address Principal Data nr. Month Schools Address List - Alphabetical per District 2018 MOTHEO: Schools District: MOTHEO 440304273 ACADEMY OF EXCELLENCE CI/S Yes English Independent Combined ACADEMY OF EXCELLENCE 1, Fichardtpark, 081-7482976 C/o Dr. Belcher & Lovedale Road, BATHO Mrs J VAN DER Septembe 1042 43 BFN, 9317 MERWE r 440304161 ACCELERATED CHRISTIAN No English Independent Intermediate PO BOX 29480, Danhof, Bloemfontein, 9310 -0514083846 Rudolf Greyling Str, ESTOIRE Mr A VAN DER Septembe 331 15 COLLEGE II/S LINDE r 440304267 ACCELERATED CHRISTIAN Yes English Independent Ordinary Sec. PO BOX 29480, , Bloemfontein, 9310 051-4471727 Rudolf Greyling Steet, Mr A VAN DER Septembe 119 9 COLLEGE SI/S LINDE r 443907314 ALBERT MOROKA Section 21 Yes English Public Ordinary Sec. Q3 PO BOX 24, Ga-Rapulana, Thaba Nchu, 9780 051-8730074 STAND NUMBER 2345, GA-RAPULANA Ms PS MOTSAMAI Septembe 1033 39 (Deputy) r 440602037 AMOHELANG I/S Section 21 No English Public Intermediate Q1 PRIVATE BAG XX506, BOTSHABELO, 051-5321608 1159 SECTION C, SECTION C Mr KP KHAKHAU August 616 18 BOTSHABELO, 9781 440303023 ARBEIDSGENOT PF/S Partly Section 21 No English Farm Primary Q1 PO BOX 19270, BLOEMSPRUIT, 051-5289900 ARBEIDSGENOT FARM, BLOEMSPRUIT MR K.K. Septembe 930 28 BLOEMFONTEIN, 9301 LESERWANE r 442607053 ASSISI PF/S Partly Section 21 No English Farm Primary Q1 PO BOX 1038, Ladybrand, LADYBRAND, 9745 -0614534132 FORT SAVAGE FARM, MARSEILLES Mr PW MOKOENA Septembe 86 4 r 442607150 ATALANTA PF/S Non-Section 21 No English Farm Primary Q1 PO BOX 318, LADYBRAND, LADYBRAND, 05192-41002 ATALANTA FARM, LADYBRAND MS A.M THULO August 22 1 9745 (Acting) 440303248 ATANG P/S Partly Section 21 No English Public Primary Q3 PO BOX 9416, NAMIBIA SQUARE, 051-4235112 8152 Namibia, NAMIBIA Mr M.J TSHABALALA Septembe 1379 37 Bloemfontein, 9300 r 440303261 ATLEHANG S/S Section 21 No English Public Ordinary Sec. -

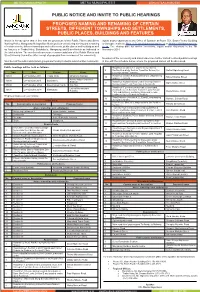

2ND PHASE RENAMING.Indd

METRO MUNICIPALITY METRO MUNISIPALITEIT LEKGOTLA LA MOTSE PUBLIC NOTICE AND INVITE TO PUBLIC HEARINGS PROPOSED NAMING AND RENAMING OF CERTAIN STREETS, DIFFERENT TOWNSHIPS AND SETTLEMENTS, Speaker PUBLIC PLACES, BUILDINGS AND FEATURES Cllr. Mxolisi Siyonzana Notice is hereby given that in line with the provisions of the Public Places and Street inputs and/or objections to the Offi ce of Speaker at Room 701, Bram Fischer Building Naming Policy, Mangaung Metropolitan Municipality is considering naming and renaming or through emails at: [email protected] or Nontsizi.Dial@mangaung. of certain streets, different townships and settlements, public places and building as well co.za. The closing date for written comments, inputs and/or objections is the 7th as features in Thaba Nchu, Botshabelo, Mangaung and Bloemfontein as indicated in November 2014. the tables below. The mentioned names are recommendations of the Public Places and Street Naming Committee after receipt of proposals from members of the community. Members of the community and stakeholders are further invited to attend public hearings Members of the public and interest groups are hereby invited to submit written comments, in line with the schedule below, where the proposed names will be discussed. Public hearings will be held as follows: Road from Sections T, L and N intersection to 9 Section D and into Section T past the School, the Mafusi Mpheteng Road. Time Date Region Venue reservoir joining T junction. th Road from Section K along Dinkung to Dikgwaseng 16h00 20 October 2014 Thaba Nchu Mmabana Stadium 10 Sidwel Xhalisa Street. opposite letamong. st Arena, Kaizer Sebothelo 16h00 21 October 2014 Botshabelo Road from Multifunctional Centre moving between Stadium 11 Sipho Saliwe Street.