Ritual and Signature in Serial Sexual Homicide

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Case Closed, Vol. 27 Ebook Free Download

CASE CLOSED, VOL. 27 PDF, EPUB, EBOOK Gosho Aoyama | 184 pages | 29 Oct 2009 | Viz Media, Subs. of Shogakukan Inc | 9781421516790 | English | San Francisco, United States Case Closed, Vol. 27 PDF Book January 20, [22] Ai Haibara. Views Read Edit View history. Until Jimmy can find a cure for his miniature malady, he takes on the pseudonym Conan Edogawa and continues to solve all the cases that come his way. The Junior Detective League and Dr. Retrieved November 13, January 17, [8]. Product Details. They must solve the mystery of the manor before they are all killed off or kill each other. They talk about how Shinichi's absence has been filled with Dr. Chicago 7. April 10, [18] Rachel calls Richard to get involved. Rachel thinks it could be the ghost of the woman's clock tower mechanic who died four years prior. Conan's deductions impress Jodie who looks at him with great interest. Categories : Case Closed chapter lists. And they could have thought Shimizu was proposing a cigarette to Bito. An unknown person steals the police's investigation records relating to Richard Moore, and Conan is worried it could be the Black Organization. The Junior Detectives find the missing boy and reconstruct the diary pages revealing the kidnapping motive and what happened to the kidnapper. The Junior Detectives meet an elderly man who seems to have a lot on his schedule, but is actually planning on committing suicide. Magic Kaito Episodes. Anime News Network. Later, a kid who is known to be an obsessive liar tells the Detective Boys his home has been invaded but is taken away by his parents. -

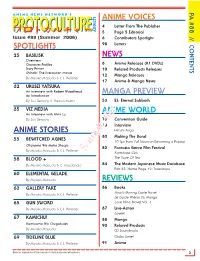

Protoculture Addicts

PA #88 // CONTENTS PA A N I M E N E W S N E T W O R K ' S ANIME VOICES 4 Letter From The Publisher PROTOCULTURE¯:paKu]-PROTOCULTURE ADDICTS 5 Page 5 Editorial Issue #88 (Summer 2006) 6 Contributors Spotlight SPOTLIGHTS 98 Letters 25 BASILISK NEWS Overview Character Profiles 8 Anime Releases (R1 DVDs) Story Primer 10 Related Products Releases Shinobi: The live-action movie 12 Manga Releases By Miyako Matsuda & C.J. Pelletier 17 Anime & Manga News 32 URUSEI YATSURA An interview with Robert Woodhead MANGA PREVIEW An Introduction By Zac Bertschy & Therron Martin 53 ES: Eternal Sabbath 35 VIZ MEDIA ANIME WORLD An interview with Alvin Lu By Zac Bertschy 73 Convention Guide 78 Interview ANIME STORIES Hitoshi Ariga 80 Making The Band 55 BEWITCHED AGNES 10 Tips from Full Moon on Becoming a Popstar Okusama Wa Maho Shoujo 82 Fantasia Genre Film Festival By Miyako Matsuda & C.J. Pelletier Sample fileKamikaze Girls 58 BLOOD + The Taste Of Tea By Miyako Matsuda & C. Macdonald 84 The Modern Japanese Music Database Part 35: Home Page 19: Triceratops 60 ELEMENTAL GELADE By Miyako Matsuda REVIEWS 63 GALLERY FAKE 86 Books Howl’s Moving Castle Novel By Miyako Matsuda & C.J. Pelletier Le Guide Phénix Du Manga 65 GUN SWORD Love Hina, Novel Vol. 1 By Miyako Matsuda & C.J. Pelletier 87 Live-Action Lorelei 67 KAMICHU! 88 Manga Kamisama Wa Chugakusei 90 Related Products By Miyako Matsuda CD Soundtracks 69 TIDELINE BLUE Otaku Unite! By Miyako Matsuda & C.J. Pelletier 91 Anime More on: www.protoculture-mag.com & www.animenewsnetwork.com 3 ○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○ LETTER FROM THE PUBLISHER A N I M E N E W S N E T W O R K ' S PROTOCULTUREPROTOCULTURE¯:paKu]- ADDICTS Over seven years of writing and editing anime reviews, I’ve put a lot of thought into what a Issue #88 (Summer 2006) review should be and should do, as well as what is shouldn’t be and shouldn’t do. -

The Culture of Capital Punishment in Japan David T

MIGRATION,PALGRAVE ADVANCES IN CRIMINOLOGY DIASPORASAND CRIMINAL AND JUSTICE CITIZENSHIP IN ASIA The Culture of Capital Punishment in Japan David T. Johnson Palgrave Advances in Criminology and Criminal Justice in Asia Series Editors Bill Hebenton Criminology & Criminal Justice University of Manchester Manchester, UK Susyan Jou School of Criminology National Taipei University Taipei, Taiwan Lennon Y.C. Chang School of Social Sciences Monash University Melbourne, Australia This bold and innovative series provides a much needed intellectual space for global scholars to showcase criminological scholarship in and on Asia. Refecting upon the broad variety of methodological traditions in Asia, the series aims to create a greater multi-directional, cross-national under- standing between Eastern and Western scholars and enhance the feld of comparative criminology. The series welcomes contributions across all aspects of criminology and criminal justice as well as interdisciplinary studies in sociology, law, crime science and psychology, which cover the wider Asia region including China, Hong Kong, India, Japan, Korea, Macao, Malaysia, Pakistan, Singapore, Taiwan, Thailand and Vietnam. More information about this series at http://www.palgrave.com/gp/series/14719 David T. Johnson The Culture of Capital Punishment in Japan David T. Johnson University of Hawaii at Mānoa Honolulu, HI, USA Palgrave Advances in Criminology and Criminal Justice in Asia ISBN 978-3-030-32085-0 ISBN 978-3-030-32086-7 (eBook) https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-030-32086-7 This title was frst published in Japanese by Iwanami Shinsho, 2019 as “アメリカ人のみた日本 の死刑”. [Amerikajin no Mita Nihon no Shikei] © The Editor(s) (if applicable) and The Author(s) 2020. -

Federal Appellate Jurisdiction Over Orders Compelling Arbitration and Staying Litigation

This page was exported from - The Arbitration Law Forum Export date: Thu Sep 30 3:49:39 2021 / +0000 GMT Arbitration Nuts and Bolts: Federal Appellate Jurisdiction over Orders Compelling Arbitration and Staying Litigation Introduction Today we look at federal appellate jurisdiction over orders compelling arbitration and staying litigation. Sections 3 and 4 of the Federal Arbitration Act (the "FAA") provide remedies for a party who is aggrieved by another party's failure or refusal to arbitrate under the terms of an FAA-governed agreement. FAA Section 3, which governs stays of litigation pending arbitration, requires courts, ?upon application of one of the parties,? to stay litigation of issues that are ?referable to arbitration? ?until arbitration has been had in accordance with the terms of the parties' arbitration agreement, providing [the party applying for a stay] is not in default in proceeding with such arbitration.? 9 U.S.C. § 3. Faced with a properly supported application for a stay of litigation of an arbitrable controversy, a federal district court must grant the stay. 9 U.S.C. § 3. Section 4 of the FAA authorizes courts to make orders ?directing arbitration [to] proceed in the manner provided for in [the [parties' written arbitration] agreement[,]? and sets forth certain procedures for adjudicating petitions or motions to compel arbitration. 9 U.S.C. § 4. It provides that when a court determines ?an agreement for arbitration was made in writing and that there is a default in proceeding thereunder, the court shall make an order summarily directing the parties to proceed with the arbitration in accordance with the terms thereof.? 9 U.S.C. -

Protoculture Addicts Is ©1987-2006 by Protoculture • the REVIEWS Copyrights and Trademarks Mentioned Herein Are the Property of LIVE-ACTION

Sample file CONTENTS 3 ○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○ P r o t o c u l t u r e A d d i c t s # 8 7 December 2005 / January 2006. Published by Protoculture, P.O. Box 1433, Station B, Montreal, Qc, Canada, H3B 3L2. ANIME VOICES Letter From The Publisher ......................................................................................................... 4 E d i t o r i a l S t a f f Page Five Editorial ................................................................................................................... 5 [CM] – Publisher Christopher Macdonald Contributor Spotlight & Staff Lowlight ......................................................................................... 6 [CJP] – Editor-in-chief Claude J. Pelletier Letters ................................................................................................................................... 74 [email protected] Miyako Matsuda [MM] – Contributing Editor / Translator Julia Struthers-Jobin – Editor NEWS Bamboo Dong [BD] – Associate-Editor ANIME RELEASES (R1 DVDs) ...................................................................................................... 7 Jonathan Mays [JM] – Associate-Editor ANIME-RELATED PRODUCTS RELEASES (UMDs, CDs, Live-Action DVDs, Artbooks, Novels) .................. 9 C o n t r i b u t o r s MANGA RELEASES .................................................................................................................. 10 Zac Bertschy [ZB], Sean Broestl [SB], Robert Chase [RC], ANIME & MANGA NEWS: North -

June Catalano, Manager DATE

City of Pleasant Hill M E M O R A N D U M TO: Mayor and City Council FROM: June Catalano, Manager DATE: January 10, 2014 SUBJECT: WEEKLY UPDATE PUBLIC WORKS AND COMMUNITY DEVELOPMENT Building Division Crossroads (2316 Monument Boulevard) – Plans have been submitted to review and approve the exterior remodel and interior shell of the building for a future tenant. This building was previously known as Ballys Total Fitness. Crossroads (2350 Monument Boulevard, #B) – Tenant improvement plans have been submitted to review and approve the tenant space for Miracle Ear. Pleasant Hill Plaza (1900 Contra Costa Boulevard) – Plans have been submitted for review and approval to remodel Starbucks. Pleasant Hill Shopping Center (552 Contra Costa Boulevard #90) – Tenant improvement plans have been submitted to review and approve the tenant space for Home Goods Store. This was previously known as Barnes & Noble. Downtown (45 Crescent Drive #A) – Tenant improvement plans have been submitted to review and approve two tenants spaces being combined to make one tenant space and located at the Clock Tower building. Engineering Division Buskirk Avenue Widening Phase 2 Improvement Project – The Project Contractor, Ghilotti Bros., Inc. (Ghilotti) and their subcontractors are preparing to switch over to the next construction Stage 1C. This next stage will include project improvements along the east side of Buskirk Avenue and Elmira Lane. Overall the project is on schedule and anticipated to be completed by September 2014. Current Buskirk Project Activities PG&E, Comcast, AT&T Utility Cutovers (Ongoing) – On schedule PG&E energized the new service cabinets for the new street lights and traffic controllers the week of December 16, 2013. -

List of Case Closed Episodes (Season 1)

List of Case Closed episodes (season 1) Ep no. Funimation dub title/Original translated Original English Jp En title Orig. Funi. airdate airdate . g. Original Japanese title "The Big Shrink" / "Roller Coaster Murder Case" January 8, May 24, 01 01 "Jet Coaster Satsujin Jiken" (ジェットコースター 1996 2004[21] 殺人事件) A man is murdered during a party and the detective Jimmy Kudo is called to solve the case. He reveals that the host is the murderer and solves the case. Jimmy and his friend, Rachel Moore then take a trip to an amusement park. While they are there a man is decapitated during a roller coaster ride. Jimmy reveals the murderer to be the man's ex-girlfriend, Haley. He shows that Haley used her necklace made of piano wire and a hook in her purse, looped the wire around the victim's neck and hooked the wire onto the roller coaster tracks during the ride. Haley explains that the victim broke up with her and she had planned a murder suicide. After solving this case Jimmy follows two suspicious men in black from the roller coaster case and watches them make a clandestine deal. Jimmy is attacked from behind by the two men and forced to take a newly developed poison that should kill him. "The Kidnapped Debutante" / "Company January May 25, 02 02 President's Daughter Kidnapping Case" 15, 1996 2004[21] "Shachō Reijō Yūkai Jiken" (社長令嬢誘拐事件) Jimmy wakes up and finds that he is now in the body of a young child as a result of the poison. -

The Exodus Road Turns to Case Closed Software to Investigate

The Exodus Road turns to Case Closed Software to Investigate Human Trafficking Globally Case Closed Software will provide The Exodus Road with secure, customized, and easy-to-use case management software to assist in their efforts to investigate and prosecute cases of human trafficking around the world. AUSTIN, Texas (PRWEB) October 16, 2020 -- The Exodus Road, a global organization dedicated to fighting human trafficking, announced today that they have adopted the industry leading investigation case management system from Austin, TX based Case Closed Software. The Exodus Road fights human trafficking by sending national and foreign operatives to suspected human trafficking locations to gather intelligence and evidence. To date, their organization has been directly involved in the rescue of nearly 1500 victims of human trafficking and the arrests of almost 600 criminals in six different countries. Using Case Closed Software, the company expects to improve these global operations and manage cases more effectively, ultimately resulting in the rescue of more and more victims. The Exodus Road began through the work of co-founders Matt and Laura Parker who, in 2010, operated a children’s home in rural Northern Thailand. During that time, Matt and Laura were exposed to marginalized people groups – targets for human trafficking. Eventually, Matt began networking with news media and local police to learn about the problem at the ground level. After a period of research, he was deputized by police and started working personally to find those trapped in slavery. Today, they lead a team of 70 staff members, many of whom are national operatives who work closely with vetted police partners. -

Case Closed: V. 19 Free

FREE CASE CLOSED: V. 19 PDF Gosho Aoyama | 192 pages | 07 Jul 2008 | Viz Media, Subs. of Shogakukan Inc | 9781421508849 | English | San Francisco, United States Case Closed (season 19) - Wikipedia Due to legal problems with the name Detective Conanthe English language releases from Funimation and Viz were renamed to Case Closed. The story Case Closed: v. 19 the high school detective Shinichi Kudo renamed as Jimmy Kudo in the English translation who was transformed into a child while investigating a mysterious organization and solves a multitude of cases while impersonating his childhood best Case Closed: v. 19 father and other characters. The anime resulted in animated Case Closed: v. 19 filmsoriginal video animationsvideo gamesaudio disc releases and live action episodes. Funimation licensed the anime series Case Closed: v. 19 North American broadcast in under the name Case Closed with the characters given Americanized names. The anime premiered Case Closed: v. 19 Adult Swim but was discontinued due to low ratings. In MarchFunimation began streaming their licensed episodes of Case Closed ; Crunchyroll simulcast them in Meanwhile, the manga was localized by Viz Mediawhich used Funimation's changed title and character names. Shogakukan Asia made its own English language localized version of the manga which used the original title and Japanese names. The anime adaptation has been well received and ranked in the top twenty in Animage ' s polls between and In the Japanese anime television ranking, Case Closed episodes ranked in the top six on a weekly basis. Both the manga and the anime have had positive response from critics for their plot and cases. -

Forensics: Crime Scene Investigation Case Closed Christina Parente University of Rhode Island

University of Rhode Island DigitalCommons@URI Senior Honors Projects Honors Program at the University of Rhode Island 2007 Forensics: Crime Scene Investigation Case Closed Christina Parente University of Rhode Island Follow this and additional works at: http://digitalcommons.uri.edu/srhonorsprog Part of the Evidence Commons, and the Laboratory and Basic Science Research Commons Recommended Citation Parente, Christina, "Forensics: Crime Scene Investigation Case Closed" (2007). Senior Honors Projects. Paper 64. http://digitalcommons.uri.edu/srhonorsprog/64http://digitalcommons.uri.edu/srhonorsprog/64 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Honors Program at the University of Rhode Island at DigitalCommons@URI. It has been accepted for inclusion in Senior Honors Projects by an authorized administrator of DigitalCommons@URI. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Forensics:Forensics: CrimeCrime SceneScene InvestigationInvestigation CASECASE CLOSEDCLOSED CSICSI atat URIURI ChristinaChristina ParenteParente CSICSI @@ URIURI WhatWhat exactlyexactly isis forensics?forensics? Forensics is the application of a broad spectrum of sciences to answer questions of interest in the legal system. A field comprised of many disciplines CSICSI @@ URIURI ExampleExample SubSub--divisionsdivisions PathologistPathologist:: MedicalMedical examinersexaminers AnthropologyAnthropology:: IdentificationIdentification ofof remainsremains EntomologyEntomology:: DecompositionDecomposition inin relationrelation toto -

Case Closed: 32 Free

FREE CASE CLOSED: 32 PDF Gosho Aoyama | 192 pages | 08 Jul 2010 | Viz Media, Subs. of Shogakukan Inc | 9781421522005 | English | San Francisco, United States Case Reopened - A Detective Conan Rewatch Podcast on Podimo The legendary samurai Toyotomi Hideyoshi has just died a second time: a historical re-enactor playing Hideyoshi has been killed at the daimyo's own Osaka Castle. Time for Conan to make history stop repeating itself--and for Osaka native Harley Hartwell to pick up a wooden sword and eke out some old- fashioned justice! Then Detective Moore attends a star-studded engagement party on Case Closed: 32 arm of idol singer Yoko Okino This Case Closed: 32 will also create new pages on Comic Vine for:. Until you earn points all your submissions need to be vetted by other Comic Vine users. This process takes no more than a few hours and we'll send you an email once approved. Tweet Clean. Cancel Update. What size image should we insert? This will not affect the original upload Small Medium How do you want the image positioned around text? Float Left Float Right. Cancel Insert. Go to Link Unlink Change. Cancel Create Link. Disable this feature for this session. Rows: Columns:. Enter the URL for the tweet you want to embed. Characters Jimmy Kudo. Story Arcs. This edit will also create new pages on Comic Vine for: Beware, you are proposing to add brand new pages to the wiki along with your edits. Make sure this is what you intended. This will likely increase the time it takes for Case Closed: 32 changes to go live. -

Richard Scarantino, Et Al. V. Barnes & Noble, Inc., Et Al. 19-CV-01320-U.S

US District Court Civil Docket as of July 29, 2019 Retrieved from the court on July 29, 2019 U.S. District Court District of Delaware (Wilmington) CIVIL DOCKET FOR CASE #: 1:19-cv-01320-CFC Scarantino v. Barnes & Noble, Inc. et al Date Filed: 07/16/2019 Assigned to: Judge Colm F. Connolly Date Terminated: 07/29/2019 Related Case: 1:19-cv-01341-CFC Jury Demand: Plaintiff Cause: 15:78m(a) Securities Exchange Act Nature of Suit: 850 Securities/Commodities Jurisdiction: Federal Question Plaintiff Richard Scarantino represented by Brian D. Long Individually and On Behalf of All Others Rigrodsky & Long, P.A. Similarly Situated 300 Delaware Avenue, Suite 1220 Wilmington, DE 19801 (302) 295-5310 Fax: (302) 654-7530 Email: [email protected] LEAD ATTORNEY ATTORNEY TO BE NOTICED Gina M. Serra Rigrodsky & Long, P.A. 300 Delaware Avenue, Suite 1220 Wilmington, DE 19801 302-295-5310 Fax: 302-654-7530 Email: [email protected] ATTORNEY TO BE NOTICED V. Defendant Barnes & Noble, Inc. Defendant Leonard Riggio Defendant George Campbell, Jr. Defendant Mark D. Carleton Defendant Scott S. Cowen Defendant William T. Dillard, II Defendant Al Ferrara Defendant Paul B. Guenther Defendant Patricia L. Higgins Defendant Irwin D. Simon Defendant Kimberly A. Van Der Zon Defendant Chapters HoldCo Inc. Defendant Chapters Merger Sub, Inc. Date Filed # Docket Text 07/16/2019 1 COMPLAINT for Violation of the Securities Exchange Act of 1934 filed with Jury Demand against Barnes & Noble, Inc., George Campbell, Jr, Mark D. Carleton, Chapters HoldCo Inc., Chapters Merger Sub, Inc., Scott S. Cowen, William T.