Can a Market-Oriented City Also Be Inclusive?

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Iconic Tower — Transformed for Today Rebuilding the Tenant Experience from the Ground Up

Iconic Tower — Transformed for Today Rebuilding the tenant experience from the ground up —————— —————— This landmark tower has been transformed A new freestanding restaurant with an engaging into a modern, sustainable, innovation hub to outdoor space will be ideal for activities; a new food support Houston’s leading creative companies — hall-style café on the ground level offers healthy designed to meet or exceed the demands and convenient menu options; new common-areas of a changing workforce, today and tomorrow. include a comfortable lobby lounge ideal for coffee, —————— connecting or disconnecting; plus access to a spa- Meticulously maintained and operated since styled fitness center featuring health and wellness this iconic property was first commissioned as activities for group or self-paced programs. a global corporate headquarters by a leading —————— energy company. 5555 San Felipe is owner-operated and —————— maintained with an eco-friendly and sustainable With a focus on helping modern organizations approach. Our award-winning project is LEED Gold inspire talent, every aspect of the renovation certified and participates in various campaigns delivers a more perfect balance between hospitality for recycling, conservation and green-building and workspace — from the arrival experience, to operations. At every level, our tenants and their three levels of new and enhanced amenities. satisfaction come first. Transformation —————— Everything your team needs to thrive M-M Properties set a vision of rebuilding the tenant experience from the ground up. There are new modern finishes, three full floors of curated amenities and light-filled spaces. There will also be a new, freestanding signature restaurant. 5555 San Felipe is an inspired and FREESTANDING RESTAURANT – ACTIVITY LAWN collaborative office environment — the destination workplace — for today’s valuable employees. -

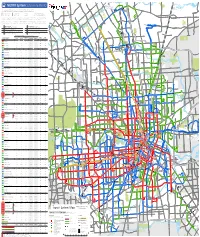

TRANSIT SYSTEM MAP Local Routes E

Non-Metro Service 99 Woodlands Express operates three Park & 99 METRO System Sistema de METRO Ride lots with service to the Texas Medical W Center, Greenway Plaza and Downtown. To Kingwood P&R: (see Park & Ride information on reverse) H 255, 259 CALI DR A To Townsen P&R: HOLLOW TREE LN R Houston D 256, 257, 259 Northwest Y (see map on reverse) 86 SPRING R E Routes are color-coded based on service frequency during the midday and weekend periods: Medical F M D 91 60 Las rutas están coloradas por la frecuencia de servicio durante el mediodía y los fines de semana. Center 86 99 P&R E I H 45 M A P §¨¦ R E R D 15 minutes or better 20 or 30 minutes 60 minutes Weekday peak periods only T IA Y C L J FM 1960 V R 15 minutes o mejor 20 o 30 minutos 60 minutos Solo horas pico de días laborales E A D S L 99 T L E E R Y B ELLA BLVD D SPUR 184 FM 1960 LV R D 1ST ST S Lone Star Routes with two colors have variations in frequency (e.g. 15 / 30 minutes) on different segments as shown on the System Map. T A U College L E D Peak service is approximately 2.5 hours in the morning and 3 hours in the afternoon. Exact times will vary by route. B I N N 249 E 86 99 D E R R K ") LOUETTA RD EY RD E RICHEY W A RICH E RI E N K W S R L U S Rutas con dos colores (e.g. -

Post Oak Plaza HOUSTON, TEXAS

Post Oak Plaza HOUSTON, TEXAS Post Oak Plaza is located in the heart of Uptown, Houston’s most vibrant and valuable mixed use region. LEVCOR.COM Post Oak Plaza 1701 Post Oak Boulevard • Houston, TX, 77056 Post Oak Plaza is a prime retail project surrounded by Houston’s most attractive upscale buyers in the heart of Uptown / The Galleria area. Arguably at Houston’s most valuable corner, Post Oak Blvd and San Felipe Rd, the project enjoys being a part of an immediate region with thriving growth, constant new residential construction, outstanding consumer income levels, and <5 min access to three major freeway thoroughfares - I-610 W (307,000 cpd), US-59 (341,000 cpd) and I-10 (338,000 cpd). In addition, the project is located seconds away from The Galleria, Houston’s premier shopping destination that has more than 30 million visitors each year and just recently completed a $250mm renovation adding an additional 130,000 SF of retail, increasing the total retail space to 2.4mm SF. Median household income levels in nearby wealthy neighborhoods - Uptown, The Memorial Villages, River Oaks, and West University - are $90,000 - $120,000. In addition, the Uptown business district is only surpassed by Downtown Houston and the Texas Medical Center, which both do not contain close to the same level of residential and retail development as Uptown. Uptown truly is Houston’s most dynamic mixed use region. MAP & GALLERY S E W N Williams Houston TowerTower ChronicleChronicle Post Oak Plaza Post Oak Blvd. & San Felipe The HamptonHampton TheThe Houston, Texas GalleriaGalleria MallMallMall WhitcoWhitco DominionDominion Residential Tower Intercontinental 2400 TowerTower Intercontinental 2400 HotelHotel McCue WEST LOOP 610 McCue MontierraMontierra Post Oak PostPost OakOak Apartments Central ApartmentsApartments 3D3D Central I,I, II,II, IIIIII MontecitoMontecito InternationalInternational I,I, II,II, IIIIII TowerTowerTower Post Oak Boulevard Lofts on 2800 PostPost OakOakOak W.W. -

RMC Managed Co-Tenancy

Rice Village A bustling, historic shopping haven tucked in the true heart of Houston. 889,000 SF of Existing Retail + Geographic Established Mixed-Use District Landscape RICE VILLAGE SPRING 1 Downtown Houston HUMBLE 2 River Oaks CYPRESS 3 Greenway Plaza 4 Galleria KATY 2 4 1 HOUSTON 3 RMC MANAGED TIMES BLVD PASADENA SUGARLAND AMHERST ST MORNINGSIDE DR MORNINGSIDE KELVIN DR KELVIN PEARLAND RICE VILLAGE 3 ROBINHOOD ST MORNINGSIDE DR KELVIN DR KIRBY DR TANGLEY ST TANGLEY ST DUNSTAN RD DUNSTAN RD BOLSOVER ST RICE BLVD RICE BLVD 1 2 3 4 New Concepts RICE VILLAGE 1 Mi Golondrina 2 Sweetgreen TIMES BLVD TIMES BLVD 3 Politan Row 4 Hopdoddy 5 Shake Shack 6 Sixty Vines AMHERST ST 7 Warby Parker MORNINGSIDE DR 8 Tecovas KELVINDR 9 Mendocino Farms KIRBY DR UNIVERSITY BLVD UNIVERSITY BLVD 5 6 7 8 9 SHAKESPEARE ST SHAKESPEARE ST RICE VILLAGE 4 Houston POIs Within 5 Miles Downtown 157,906 EMPLOYEES Midtown 9,808 EMPLOYEES Museum District POINTS OF INTEREST 8.7 MILLION VISITORS/YEAR Texas Medical Center 106,000 EMPLOYEES Rice University 17,080 STUDENTS & STAFF Montrose 17,398 HOUSEHOLDS $113,678 AVERAGE HHI Southampton NEIGHBORHOODS 904 HOUSEHOLDS $247,987 AVERAGE HHI West University 6,261 HOUSEHOLDS $282,693 AVERAGE HHI RICE VILLAGE 5 Outstanding Density 10 MILES & Buying Power SECONDARY TRADE AREA 5 MILES TOTAL VISITORS / YEAR 3+ TRIPS ABROAD IN 3 YEARS 1.2 Million 2.5x National Average UNIQUE VISITS / YEAR GIVING TO THE ARTS 3.4 Million 1.87x National Average PRIMARY TRADE AREA Dense demographics with strong Ideal location minutes away daytime and evening population, from the Texas Medical The Primary Trade Area shows the home location of the top 40% of visitors to Rice Village Rice Village is an around-the-clock Center, Downtown, River in the last 12 months, based on mobile device data. -

The Midtown Study Summary

By 2035, the eight-county Houston-Galveston region is expected to grow by an additional 3.5 million people. The Livable Centers program is a new strategy in H-GAC’s 2035 Regional Transportation Plan to address this growth. The Houston-Galveston Area Council and the City of Houston co-sponsored this Livable Centers Study for the Ensemble/HCC light rail station area in Midtown. Livable Centers are safe, sustainable, mixed-use neighborhoods where people can live, work, and play with less reliance on their cars. Well connected destinations make walking, bicycling, and transit more convenient. Livable Centers create unique, identifi able places, bolster civic pride, and focus resources for economic development. ENSEMBLE/HCC A Vision for a Livable Center Houston-Galveston Area Council CLOSE TO EVERYTHING The Midtown neighborhood’s Ensemble/HCC light rail station is at the heart of Houston’s urban core. The neighborhood is within fi ve miles of Houston’s four major employment centers, arts, entertainment, sports and major convention facilities, fi ve universities and half a dozen graduate institutions. The area is extremely connected with easy access to Downtown, the Texas Wortham Alley Center Theatre Medical Center, the Museum District, Jones Hobby Center Hall the University of Houston, Texas DOWNTOWN Minute Maid Park Southern University, Reliant Center, George R. Brown Convention Center Neartown, Greenway Plaza, Uptown, 2 mile radius Toyota Center and The Galleria. The location will 1 mile radius soon be even more convenient with MIDTOWN NEARTOWN the completion of fi ve new light rail University of THIRD WARD lines connected to the existing Main Menil CollectionSt. -

The Galleria Current Web Lease Plan 5085 Westheimer Rd, Suite 4850 Houston, TX 77056 Modified: September 13, 2021 CORP # 7621

This exhibit is provided for illustrative purposes only, and shall not be deemed to be a warranty, representation or agreement by Landlord that the Center, Common Areas, buildings and/or stores will be as illustrated on this exhibit, or that any tenants which may be referenced on this exhibit will at any time be occupants of the Center. Landlord reserves the right to modify size, configuration and occupants of the Center at any time. THE OCEANAIRE SEAFOOD ROOM RETAIL FOREVER 21 #JOEY# #THE WEBSTER# OQUA J. CREW DEL FRISCO'S GRILLE PLUSH RX JD SPORTS SLEEP NUMBER FORUM BY GEORGIO PELI PELI #NOBU# ECCO CHEESECAKE #MUSAAFER# FACTORY FIG & OLIVE BLANCO TACOS + TEQUILA Q SHAKE #DANCE WITH ME# SHACK BROOKS BROTHERS INDOCHINO KIDS ATELIER RETAIL TOUS TAG HEUER AESOP SGH TUMI ST. JOHN COLE HAAN UNTUCKIT LACOSTE ROBIN'S JEAN RAG & BONE OPTICA OMEGA TIFFANY & CO. WOLFORD JIMMY CHOO SALVATORE SAINT LAURENT GUCCI PANERAI FENDI LOUIS VUITTON MONCLER FERRAGAMO LOUIS VUITTON BULGARI MEN'S PORSCHE DESIGN BURBERRY RETAIL MICHAEL KORS SAMSUNG RALPH LAUREN MONTBLANC ALLSAINTS ARITZIA TRUNK SCOTCH & SODA MCM CREED HOUSTON FACTORY ROBERT GRAHAM BREITLING OFF THE WALL DAVID YURMAN DE BEERS HUBLOT LEVI'S RETAIL MAJE PAIGE COACH FABERGE ZARA SANDRO CHARLES JOHNSTON & RETAIL TYRWHITT TOD'S AKRIS KATE SPADE ROLEX RETAIL MURPHY RETAIL PRADA STARBUCKS CELINE CHANEL VERSACE SEPHORA TOM FORD STUART WEITZMAN VALENTINO 7 FOR ALL MANKIND LORO PIANA BALENCIAGA CASPER TORY BURCH TED BAKER LONDON GOLDEN GOOSE BOSS HUGO ANN TAYLOR BOTTEGA VENETA AG ADRIANO GOLDSCHMIED CHRISTIAN LOUBOUTIN CH CAROLINA HERRERA JOHN VARVATOS ERMENEGILDO EXPRESS WOMEN ZEGNA RETAIL BROW ART TONI & GUY 23 #OFF THE WALL# THE GAP BEAUTY & BEYOND B&B NEWS & MORE GIFTS OF TEXAS BANANA REPUBLIC TALBOTS FABLETICS TESLA MOTORS NESPRESSO BROW ART 23 H&M BRIGHTON COLLECTIBLES OSHKOSH B' GOSH DANIELLE EMON JOURNEYS KIDZ AMERISLEEP JANIE and JACK RETAIL HOPE & HENRY TOMMY BAHAMA PELOTON RETAIL EARTHBOUND TRADING ADIDAS COMPANY CHICO'S LOVESAC EYE CANDY COUTURE LOFT J. -

Dissimilarity and the North American Gallerias of Houston and Toronto

A Tale of Two Cities: Dissimilarity and the North American Gallerias of Houston and Toronto On the surface, the North American cities of Houston and Toronto share very lit- tle in common. Their climates, geographies, cultures, and urban forms are radi- cally different. Their political sensibilities and civic aspirations reveal remarkably divergent philosophies in regard to the public realm. However, both cities rep- resent dynamic, global, cosmopolitan places that are important at national and international scales. Both cities act as primary gateways for immigrants to their respective nations. Each witnessed rapid expansion and transformative devel- opment in the 1970s that shifted their economic and cultural significance on a global scale. It was during this time that both cities received several key architectural land- GREGORY MARINIC marks, and more particularly, a destination-type, regional shopping com- University of Houston plex modelled on the Galleria Emanuele II in Milan. These new buildings—the Houston Galleria and the Toronto Eaton Centre—reflected a shift toward alterna- tive approaches to retail, urbanism, and the public realm in their respective cities. Through the lens of consumption, this essay examines the divergent histories of the Houston Galleria and Toronto Eaton Centre in regard to their design, plan- ning, and development agendas. It discusses larger urban issues that emerged at a critical moment in history when Houston and Toronto would embark upon vastly different paths of urban growth. Developmental practices evidenced in the design and construction of these gallerias would come to define contrasting urban cultures which evolved incrementally over the next thirty years. PLACELESSNESS AND UTOPIA Shopping malls represent contemporary North American and increasingly global cultural sensibilities and desires. -

Aloft Houston by the Galleria Four Points by Sheraton Houston Southwest 5415 Westheimer Road 2828 Southwest Freeway Houston,TX

Aloft Houston by the Galleria Four Points by Sheraton Houston Southwest 5415 Westheimer Road 2828 Southwest Freeway Houston,TX 77056 Houston,TX 77098 Phone: 713-622-7010 Phone: 713-942-2111 Fax: 713-622-7025 Fax: 713-942-9934 Club Quarters Hampton Inn and Suites Medical Center 720 Fannin Street 1715 Old Spanish Trail Houston,TX 77002 Houston,TX 77054 Phone: 713-224-6400 Phone: 713-797-0040 Fax: 713-224-6417 Fax: 713-797-0094 Courtyard by Marriott Downtown Hampton Inn Houston Galleria 916 Dallas Street 4500 Post Oak Parkway Houston,TX 77002 Houston,TX 77027 Phone: 832-366-1600 Phone: 713-871-9911 Fax: 832-366-1601 Fax: 713-871-9958 Courtyard by Marriott Galleria Hilton Americas Houston - Headquarter Hotel 2900 Sage Road 1600 Lamar Street Houston,TX 77056 Houston,TX 77010 Phone: 713-622-3611 Phone: 713-577-8000 Fax: 713-622-3204 Fax: 713-577-6140 Crowne Plaza Houston Downtown Hilton Houston Post Oak 1700 Smith Street 2001 Post Oak Boulevard Houston,TX 77002 Houston,TX 77056 Phone: 713-739-8800 Phone: 713-961-9300 Fax: 713-739-8806 Fax: 713-623-6685 Crowne Plaza River Oaks Hilton Houston Westchase 2712 Southwest Freeway 9999 Westheimer Road Houston,TX 77098 Houston,TX 77042 Phone: 713-523-8448 Phone: 713-974-1000 Fax: 713-523-3689 Fax: Not Listed Doubletree by Hilton Houston Greenway Plaza Hotel Hotel Derek 6 Greenway Plaza East 2525 West Loop South Houston,TX 77046 Houston,TX 77027 Phone: 713-629-1200 Phone: 713-297-4366 Fax: 713-629-4706 Fax: 713-267-4393 Doubletree Hotel Houston Downtown Hotel ICON 400 Dallas Street 220 Main Street Houston,TX -

City Under Glass

20 CITE 65 : WINTER 2 0 0 5 [he Galleria. Weslhoimei Boulevard, circa 19/1, HAiulh. Oboto + Kassnbuum, architects, with Neuham and Tovlor. Below: Ihe lour stages Galleria 111971), Galleria II (19/7), Gollcmi III (1994). and Gallena IV (2007). STREETLEVEl ram. RINK LEVEL CITY UNDER GLASS The Galleria offers consumers a look at nearly everything, including its own version of sprawl BY BRUCE C. W E B B IN MANY WAYS, MODERN HOUSTON and the Galleria grew up together. It was in 1969 that then-tyro developer Gerald D. Mines began to reinvent the shopping center as a street under glass (with apologies to the magnificent |9 l h century Galleria Vittorio Kmanuele in Mil.mi. Paired with the Harris County Domed Stadium built in 1965, another exem- plar of the architecture ol technical defiance, the Galleria helped make Houston the air conditioning capital of the world, a city with self-satisfied buildings, closed systems of the well-tempered environment thai were suitable for anywhere and perfect lur inhospi- table climates, be they along the Inner Loop or in the vacuum of outer space. It was the age of the astronauts—Houston was transformed overnight into Space City with the arrival of the manned space program—but it was the builders and developers and their projects who were becoming local legends. CITE 65 : WINTER 2005 21 Out of this Zeitgeist, developer bars, restaurants, even a b o w l i n g alley different precincts w i t h different charac- Stretched as it was, the Galleria Kenneth Schnirzcr began to build (long gone) and lour movie theaters. -

Becoming the Ranch House City

relatively short period of time. Houston grew at a phenom- Houston: Becoming enal rate during the decades immediately after World War II. Its population soared from 384,514 in 1940 to 1,595,138 in 1980.1 A booming economy fueled the growth, which city the Ranch House City leaders guided through an aggressive annexation policy. By Stephen James As late as the 1940s, Houston was a compact city of seventy-five square miles. Its boundaries extended no ouston is a vast city that spreads to the horizon in all farther than Kirby Drive on the west, Brays Bayou on the Hdirections. Gleaming commercial districts punctu- southwest, and Sims Bayou on the southeast. The Heights, ate its sprawl, but the landscape is a blanket of residential Rice Institute, and the new Texas Medical Center were neighborhoods. They define its architectural character. on the edge of town. Today, this area defines the urban They tell us how and when the city grew. core, a central business district ringed by the city’s earliest Every urban area reflects the architectural styles that pre- suburbs. A 1947 land use map (below) shows that most vailed during the years of its greatest growth. The industrial residential areas—highlighted in shades of gray accord- cities of the Northeast and Midwest, which boomed in the ing to density—developed on a grid pattern with small nineteenth century, are known for their many neighbor- compact lots.2 An informal survey of these areas today hoods of narrow row houses wrapped in picturesque brown- shows that architectural types varied according to income. -

Richmond Square

theGalleria WILLIAMS TOWER LAKES ON POST OAK MANHATTAN 3009 POST OAK CONDOMINIUMS THE PLAZA ON RICHMOND BROADSTONE POST OAK APARTMENTS GALLERIA OAKS RICHMOND AVENUE FUTURE APARTMENTS MIXED-USE POST OAK BOULEVARD DEVELOPMENT IH 610 | WEST LOOP FREEWAY RICHMOND SQUARE RICHMOND SQUARE HOUSTON, TEXAS | EXECUTIVE SUMMARY Holliday Fenoglio Fowler, L.P. acting by and through Holliday GP Corp., a Texas licensed real estate broker (“HFF”). | RICHMOND SQUARE The Gateway to the Galleria Aerial View Facing Northeast KEY Employment 1 Lakes on Post Oak 22 2 3009 Post Oak - Alliantgroup HQ 23 MEMORIAL DR 3 Williams Tower - Hines HQ 20 4 Post Oak Central 5 Four Oaks Place- BHP Billiton HQ 11 6 6 Amegy Bank HQ 5 15 19 Mixed-Use 9 10 7 Galleria 3 4 14 8 Proposed Mixed Use 18 9 River Oaks District 13 10 BLVD Place- Whole Foods 11 Uptown Park 2 Retail 21 12 The Plaza on Richmond 7 13 Centre at Post Oak POST OAK BLVD 17 14 Post Oak Center 15 Highland Village - Central Market Residential 1 8 16 Lamar Terrace ($550K - $1.8M) 17 Manhattan Condos ($600K-$1.6M) 12 18 Afton Oaks ($500K-$3.5M) 19 Tanglewood ($750k - $6.2M) RICHMOND AVE 16 20 River Oaks ($1.6M-$17M) Points of Interest RICHMOND SQUARE SAGE RD 21 Gerald D. Hines Waterwall Park 22 Memorial Park 23 River Oaks Country Club PROPERTY OVERVIEW Address: 5005 - 5133 Richmond Ave In-Place Occupancy 100.0% Houston, TX 77056 Traffic Counts Richmond Ave.: 48,500 VPD Location: Richmond at I-610 I-610: 317,000 VPD Year Built 1989 Total: 365,500 VPD Net Rentable Area 88,446 SF Tenants Best Buy, Cost Plus World Market, -

Houston, Texas|October 19 21, 2016

DOWNTOWN HOTELS HOUSTON, TEXAS|OCTOBER 1921, 2016 1. Aloft Houston Downtown 7 blocks 2. Club Quarters Hotel 7 blocks 20 4 3. Courtyard Houston 18 Downtown/Convention Center 7 blocks 4. DoubleTree by Hilton Hotel 37 12 Houston Downtown 12 blocks 15 5. Embassy Suites Houston - Downtown 1 block 16 6. Four Seasons Hotel Houston 3 blocks 32 11 13 9 7. Hilton Americas - Houston skywalk 3 8. Holiday Inn Express & Suites Houston 28 26 1 2 39 Downtown Convention Center 2 blocks 36 40 14 17 9. Hotel Icon, Autograph Collection 13 blocks 38 23 10. Hampton Inn/Homewood Suites 34 35 42 30 6 by Hilton Downtown 2 blocks 11 . Holiday Inn Houston Downtown 11 blocks 29 24 31 41 12. Hyatt Regency Houston 10 blocks 19 27 5 25 21 10 13. JW Marriott Houston Downtown 8 blocks 22 7 blocks 33 14 . Magnolia Hotel Houston 7 15. Residence Inn Houston Downtown/Convention Center 7 blocks GALLERIA/GREENWAY HOTELS 8 16. Springhill Suites Houston 19 . Courtyard by Marriott Galleria 9 miles Downtown/Convention Center 7 blocks 20. Crowne Plaza Galleria 8 miles 17. The Sam Houston Hotel 9 blocks 21. Crowne Plaza Houston River Oaks 5 miles 18. Whitehall Hotel Houston 14 blocks 22. DoubleTree by Hilton Hotel Houston Greenway Plaza 6 miles 23. DoubleTree by Hilton Hotel + Suites Houston by the Galleria 9 miles METRORail Lines 24. Embassy Suites by Hilton Houston Near the Galleria 8 miles Red Line (Main Street) 25. Four Points by Sheraton Houston Greenway Plaza 5 miles Purple Line (Southeast Line) 26.