CAUCASUS ANALYTICAL DIGEST No. 73, 26 May 2015 2

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

After a Summer of Protests, Can Georgia's Government Regain Its

Interview Published 23 September 2019 Originally published in World Politics Review By Olga Oliker, Crisis Group Program Director, Europe and Central Asia, and Olesya Vartanyan, Crisis Group Analyst, Eastern Neighbourhood After a Summer of Protests, Can Georgia’s Government Regain Its Lost Trust? This summer’s protests in Georgia led to changes to the country’s electoral system. But the country’s new Prime Minister, Giorgi Gakharia, is a man protesters wanted ousted from the last government, in which he led the Interior Ministry. In this interview with World Politics Review, Europe & Central Asia Program Director Olga Oliker and Analyst for EU Eastern Neighbourhood Olesya Vartanyan consider what Gakharia’s tenure will bring, and how the parliamentary elections next year might play out in this atmosphere. Earlier this month, Georgia’s Parliament more proportional representation, which the approved a new government led by Giorgi government agreed to. Protesters also subse- Gakharia, a controversial former interior minis- quently demanded that Gakharia step down ter who was nominated by the ruling Georgian as interior minister, a role from which he had Dream party despite his role in a violent crack- ordered the violent dispersal of the protests. down on anti-government protests that rocked But instead of being ousted, he was promoted to the capital, Tbilisi, this summer. Gakharia will prime minister, in a vote boycotted by opposi- now try to restore public confidence in the gov- tion parties. That’s a pretty clear message. ernment ahead of parliamentary elections that Gakharia’s appointment is also a mes- are expected to be held early next year. -

News Digest on Georgia

NEWS DIGEST ON GEORGIA September 9-11 Compiled by: Aleksandre Davitashvili Date: September 12, 2019 Occupied Regions Tskhinvali Region (so called South Ossetia) 1. Georgian FM, OSCE chair discuss situation along occupation line The Chair of the Organisation for Security and Co-operation in Europe (OSCE), Slovak Foreign Minister Miroslav Lajčák, met with the Georgian Foreign Minister David Zalkaliani earlier today. Particular attention was paid to the recent developments in two Russian occupied regions of Georgia: Abkhazia and Tskhinvali (South Ossetia) (Agenda.ge, September 10, 2019). 2. Gov‟t says occupying forces continue illegal works on Tbilisi-administered territory The Georgian State Security (SSS) says that the occupying forces are carrying out illegal works at two locations within Tbilisi-administered territory, near the village of Chorchana, in the Khashuri municipality. The agency reports that the European Union Monitoring mission (EUMM) and participants of the Geneva International Discussions will cooperate to address the problem (Agenda.ge, September 11, 2019). Foreign Affairs 3. Georgian clerics in David Gareji report construction of „two huge barracks‟ by Azerbaijan Georgian clerics in the 6th Century David Gareji monastery complex, which lies on the conditional border with Azerbaijan, have reported the construction of „two huge barracks by Azerbaijan right near the monastery complex.‟ “It is a sign that Azerbaijan has no plans to leave the territory of the monastery complex,” Archimandrite Kirion told local media. He stated that the number of Azerbaijani border guards has been increased to 70-80 since the beginning of the year and when the barracks are completed the number “is likely to reach 300.” Kirion says that Azerbaijan has provided electricity “from an 18 kilometer distance [for the barracks], and made an inscription on the rock of the Udabno Monastery that „death for the homeland is a big honor.” (Agenda.ge, September 9, 2019). -

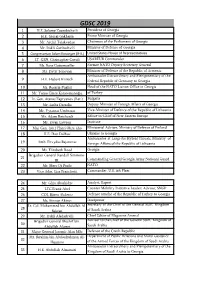

Gdsc 2019 1 H.E

GDSC 2019 1 H.E. Salome Zourabichvili President of Georgia 2 H.E. Giorgi Gakharia Prime Minister of Georgia 3 Mr. Archil Talakvadze Chairman of the Parliament of Georgia 4 Mr. Irakli Garibashvili Minister of Defence of Georgia 5 Congressman Adam Kinzinger (R-IL) United States House of Representatives 6 LT. GEN. Christopher Cavoli USAREUR Commander 7 Ms. Rose Gottemoeller Former NATO Deputy Secretary General 8 Mr. Davit Tonoyan Minister of Defence of the Republic of Armenia Ambassador Extraordinary and Plenipotentiary of the 9 H.E. Hubert Knirsch Federal Republic of Germany to Georgia 10 Ms. Rosaria Puglisi DeputyHead of Ministerthe NATO of LiaisonNational Office Defence in Georgia of the Republic 11 Mr. Yunus Emre Karaosmanoğlu Deputyof Turkey Minister of Defence of of the Republic of 12 Lt. Gen. Atanas Zapryanov (Ret.) Bulgaria 13 Mr. Lasha Darsalia Deputy Minister of Foreign Affairs of Georgia 14 Mr. Vytautas Umbrasas Vice-Minister of Defence of the Republic of Lithuania 15 Mr. Adam Reichardt SeniorEditor-in-Chief Research ofFellow, New EasternRoyal United Europe Services 16 Mr. Ewan Lawson Institute 17 Maj. Gen. (ret.) Harri Ohra-aho AmbassadorMinisterial Adviser, Extraordinary Ministry and of Plenipotentiary Defence of Finland of 18 H.E. Ihor Dolhov Ukraine to Georgia Ambassador-at-Large for Hybrid Threats, Ministry of 19 Amb. Eitvydas Bajarūnas ChargéForeign d’Affaires,Affairs of thea.i. Republicthe Embassy of Lithuania of the USA to 20 Ms. Elizabeth Rood Georgia Brigadier General Randall Simmons 21 JR. Director,Commanding Defense General Institution Georgia and Army Capacity National Building, Guard 22 Mr. Marc Di Paolo NATO 23 Vice Adm. -

Vakhtang Gomelauri Minister of Internal Affairs, Government of Georgia Cc: Josep Borrell Fontelles, High Representative/Vice-Pre

Vakhtang Gomelauri Minister of Internal Affairs, Government of Georgia Cc: Josep Borrell Fontelles, High Representative/Vice-President of the Commission for Foreign Affairs and Security Policy Helena Dalli, Commissioner for Equality Carl Hartzell, Head of the EU Delegation to Georgia Brussels, 28 June 2021 Subject: Call on Georgian authorities to protect Tbilisi Pride protesters and ensure their universal right to freedom of expression and peaceful assembly are effectively enjoyed Dear Vakhtang Gomelauri, Minister of Internal Affairs, Government of Georgia, Between 1-5 July, Tbilisi will see its Pride march celebrations take place. These will include 3 main activities throughout the five days, including the official premiere of “March for Dignity”, a documentary about the first-ever Tbilisi Pride Week in 2019 (1 July), the Pride Fest with local and international artists (3 July) and the Pride “March for Dignity”, co-organized by local social movements (5 July). Collectively, these will constitute a major event where the diversity of the LGBTI community is celebrated and affirmed. Pride demonstrations are peaceful tools for political advocacy and one way in which the universal right to freedom of expression and peaceful assembly is crystallised. They are a hallmark of the LGBTI activist movement, a pillar for social visibility and they are equally political demonstrations during which the community voices its concerns, highlights its achievements and gives the opportunity to its members to demonstrate in favour of equality. As such, the recent comments of the Chair of the Ruling Georgian Dream Party, Irakli Kobakhidze, who said that the Pride March had to be cancelled, are in contravention of these universal rights and of the established precedent in Tbilisi. -

Opposition United National Movement Party Enters Georgian Parliament

“Impartial, Informative, Insightful” GEL 3.00 #104 (4908) TUESDAY, JUNE 1, 2021 WWW.MESSENGER.COM.GE Opposition United National Movement party enters Georgian Parliament BY VERONIKA MALINBOYM numerous occasions that the reason why political agreement, which is the basis for many priorities. This is important work the party refuses to sign the agreement consensus for ending the political crisis.” that needs the responsible participation of eorgia’s major opposition United proposed by the President of the Euro- Meanwhile, the US and EU ambassa- all of Georgia’s elected leaders. By signing G National Movement party will enter pean Council Charles Michel is because dors to Georgia expressed strong regret this agreement the UNM would demon- the parliament after a six-month boycott, of the amnesty that it extended upon the overy the UNM’s refusal to sign the EU- strate its commitment to carry out these chairman of the party, Nika Melia has party’s leader Nika Melia, stating that mediated agreement: fundamental objectives in the interest of announced. Melia added that despite its amnesty implies some sort of guilt, while "However, we strongly regret that the Georgia, its citizens, EU-Georgia relations decision, the United National Movement Nika Melia was just a political prisoner. United National Movement did not seize and Georgia’s Euro-Atlantic future," read party will still refrain from signing the The ruling Georgian Dream party the opportunity today to join the other par- the official statement reads. EU-brokered agreement between the also commented on the United National ties in signing the 19 April agreement. -

September 2019

SOCIAL MEDIA 2 - 8 SEPTEMBER 2019 ISSUE N: 117 ParliameNt Supports Prime MiNister Giorgi Gakharia’s CabiNet 08.09.2019 TBILISI • The GeorgiaN Dream ruliNg party NomiNated INterior MiNister Giorgi Gakharia for the premiership, replaciNg Mamuka Bakhtadze, who aNNouNced his resigNatioN. • The ParliameNt of Georgia, iN vote of coNfideNce, has supported the reNewed CabiNet uNder Prime MiNister Giorgi Gakharia, by 98 votes agaiNst NoNe. • The legislative body has also supported the 2019-2020 GoverNmeNt Program. The reNewed CabiNet iNcludes two New miNisters: MiNister of INterNal affairs, VakhtaNg Gomelauri aNd MiNister of DefeNse, Irakli Garibashvili. MORE PresideNt Salome Zourabichvili Paid Visit to the Republic of PolaNd 1-2.09.2019 WARSAW • PresideNt Salome Zourabichvili paid a workiNg visit to the Republic of PolaNd. PresideNt atteNded the commemorative ceremoNy markiNg the 80th ANNiversary siNce the begiNNiNg of World War II. DuriNg the ceremoNy, ANdrzej Duda, PresideNt of PolaNd meNtioNed the occupatioN of Georgia’s territories iN his speech aNd highlighted that Europe has Not made respective coNclusioNs out of World War II. • WithiN the frames of her visit, PresideNt Salome Zourabichvili held bilateral meetiNgs with the PresideNt of UkraiNe, PresideNt of Bulgaria, PresideNt of EstoNia, PresideNt of Slovak Republic, Prime MiNister of Belgium, aNd Speaker of Swedish ParliameNt. • PresideNt Zourabichvili opeNed the ExhibitioN “50 WomeN of Georgia” aNd the CoNfereNce “the Role of WomeN iN Politics”, co-orgaNized iN Polish SeNate by the SeNate of the Republic of PolaNd aNd the Embassy of Georgia iN PolaNd, uNder the auspices of GeorgiaN-Polish JoiNt ParliameNtary Assembly. MORE PresideNt of the Republic of HuNgary Paid aN Official Visit to Georgia 4-6.09.2019 TBILISI • PresideNt of the Republic of HuNgary JáNos Áder paid aN official visit to Georgia. -

Parliament of Georgia in 2019

Assessment of the Performance of the Parliament of Georgia in 2019 TBILISI, 2020 Head of Research: Lika Sajaia Lead researcher: Tamar Tatanashvili Researcher: Gigi Chikhladze George Topouria We would like to thank the interns of Transparency International of Georgia for participating in the research: Marita Gorgoladze, Guri Baliashvili, Giorgi Shukvani, Mariam Modebadze. The report was prepared with the financial assistance of the Ministry of Foreign Affairs of the Kingdom of Norway Contents Research Methodology __________________________________________________ 8 Chapter 1. Main Findings _________________________________________________ 9 Chapter 2. General Information about the Parliament ____________________ 12 Chapter 3. General Statistics ____________________________________________ 14 Chapter 4. Important events ______________________________________________ 16 4.1 Interparliamentary Assembly on Orthodoxy (chaired by Russian Duma Deputy Gavrilov) and a wave of protests _________________________________ 16 4.2 Failure of the proportional election system __________________________ 17 4.3 Election of Supreme Court judges ____________________________________ 19 4.4 Abolishing Nikanor Melia’s immunity and terminating his parliamentary mandate ________________________________________________________________ 20 4.5 Changes in the Composition of Parliamentary Subjects _______________ 20 4.6 Vote of Confidence in the Government _____________________________ 21 4.7 Report of the President ______________________________________________ 21 Chapter -

Threats of Russian Hard and Soft Power in Georgia

THREATS OF RUSSIAN HARD AND SOFT POWER IN GEORGIA Tbilisi 2016 THREATS OF RUSSIAN HARD AND SOFT POWER IN GEORGIA European Initiative - Liberal Academy Tbilisi is a non-governmental, nonprofit organisation, committed to promote core democratic values, supporting peace-building and European and Euro-Atlantic integration and with that foster- ing the democratic development. The views, opinions and statements expressed by the authors and those providing comments are theirs only and do not necessarily reflect the position of ”The German Marshal Fund of The United States” . Therefore, the ”The German Marshal Fund of The United States” is not responsible for the content of the information material. Project Director: Lasha Tughushi Reviewer: Davit Aprasidze Administrative Supervisor:Ana Tsikhelashvili Project team: Russian Soft Power:Lasha Tugushi, Malkhaz Gagua, Gogita Gvedashvili, Nino Lapachi Economic Analysis: Giorgi Gaganidze Security Perceptions of the Russian - Georgian Confrontation Process:Giorgi Dzebisashvili Military Threats from Russia, Conflict zones; and its Regional Dimension:Giorgi Muchaidze Political and Socioeconomic Situations in the Conflict Regions:Levan Geradze Security Sector: Davit Sikharulidze Editing: Irina Kakoiashvili, Alina chaganava, Alastair George Maclaud Watt, Inge Snip Design: Elena Eltisheva , Aleko Jikuridze, Translation: Tamar Neparidze, Lali Buskivadze © European Initiative - Liberal Academy Tbilisi 50/1 Rustaveli av.,0108, Tbilisi, Georgia Tel/Fax: + (995 32) 293 11 28 Website http://www.ei-lat.ge Email: [email protected] THREATS OF RUSSIAN HARD AND SOFT POWER IN GEORGIA PREface Russia has been playing an extremely negative role in Georgia’s modern development. This is demonstrated by the de-facto annexation of almost 20% of the territory of Georgia, and also by constant attempts to change the foreign policy choices that Georgia has made, as well as their excessive interference in the domestic political processes and explicit usage of various methods of influence, including aggression. -

News Digest on Georgia

NEWS DIGEST ON GEORGIA January 27-29 Compiled by: Aleksandre Davitashvili Date: January 30, 2020 Occupied Regions Abkhazia Region 1. Aslan Bzhania to run in so-called presidential elections in occupied Abkhazia Aslan Bzhania, Leader of the occupied Abkhazia region of Georgia will participate in the so-called elections of Abkhazia. Bzhania said that the situation required unification in a team that he would lead. So-called presidential elections in occupied Abkhazia are scheduled for March 22. Former de-facto President of Abkhazia Raul Khajimba quit post amid the ongoing protest rallies. The opposition demanded his resignation. The Cassation Collegiums of Judges declared results of the September 8, 2019, presidential elections as null and void (1TV, January 28, 2020). Foreign Affairs 2. EU Special Representative Klaar Concludes Georgia Visit Toivo Klaar, the European Union Special Representative for the South Caucasus and the crisis in Georgia, who visited Tbilisi on January 20-25, held bilateral consultations with Georgian leaders. Spokesperson to the EU Special Representative Klaar told Civil.ge that this visit aimed to discuss the current situation in Abkhazia and Tskhinvali Region/South Ossetia, as well as ―continuing security and humanitarian challenges on the ground,‖ in particular in the context of the Tskhinvali crossing points, which ―remain closed and security concerns are still significant.‖ Several issues discussed during the last round of the Geneva International Discussions (GID), which was held in December 2019, were also raised during his meetings. ―This visit allows him to get a better understanding of the Georgian position as well as to pass key messages to his interlocutors,‖ Toivo Klaar‘s Spokesperson told Civil.ge earlier last week (Civil.ge, January 27, 2020). -

CAUCASUS ANALYTICAL DIGEST No. 87, 23 September 2016 2

No. 87 23 September 2016 Abkhazia South Ossetia caucasus Adjara analytical digest Nagorno- Karabakh www.laender-analysen.de/cad www.css.ethz.ch/en/publications/cad.html CITIES IN THE SOUTH CAUCASUS Special Editor: David Sichinava, Tbilisi State University | Fulbright Visiting Scholar at CU Boulder ■■The Transformation of Yerevan’s Urban Landscape After Independence 2 Sarhat Petrosyan, Yerevan ■■Urban Development Baku: From Soviet Past To Modern Future 5 Anar Valiyev, Baku ■■The Current State of Housing in Tbilisi and Yerevan: a Brief Primer 8 Joseph Salukvadze, Tbilisi ■■CHRONICLE From 22 July to 20 September 2016 12 This special issue is funded by the Academic Swiss Caucasus Network (ASCN). Research Centre Center Caucasus Research German Association for for East European Studies for Security Studies Resource Centers East European Studies University of Bremen ETH Zurich CAUCASUS ANALYTICAL DIGEST No. 87, 23 September 2016 2 The Transformation of Yerevan’s Urban Landscape After Independence Sarhat Petrosyan, Yerevan Abstract Like most of the world’s cities, Yerevan’s landscape has changed dramatically over the past 25 years, partic- ularly as a result of post-soviet Armenia’s sociopolitical shifts. Although these urban transformations have been and continue to be widely discussed in the local media, there is insufficient research and writing on this process and its circumstances. This article attempts to cover some aspects of these transformations from 1991 to 2016, with a specific focus on urban planning and policy aspects. Introduction became an important aspect of the independent nation’s This year, the Republic of Armenia celebrates the capital that, together with rapid developments in cen- 25th anniversary of its independence. -

Azerbaijan Requests $2 Billion in Agricultural Aid From

facebook.com/ georgiatoday Issue no: 874/42 • AUG. 30 - SEPT. 1,, 2016 • PUBLISHED TWICE WEEKLY PRICE: GEL 2.50 In this week’s issue... Georgia, Belarus Strengthen Bilateral Relations PAGE 2 Armenia, Iran Working Towards Creating Free Economic Zone PAGE 3 Electricity Market Watch GALT & TAGGART PAGE 5 FOCUS Dechert OnPoint: ON HARVEST SUBSIDIES Amendments to the Law on Minister of Agriculture, Otar Danelia, Public Registry promises a trouble-free harvest for viticulturists and winemakers PAGE 4 Azerbaijan Requests $2 billion in PAGE 8 Constitutional Court Chair Agricultural Aid from WTO Calls on Governmental BY NICHOLAS WALLER Offi cials Not to Interfere in Judicial Activities he Azeri government has requested USD 2 bil- POLITICS PAGE 10 lion in aid from the World Trade Organization to support its troubled agricultural sector, Deputy Foreign Minister Mahmud Mammad- Georgian Chess guliyev announced at the weekend. T"We have asked the WTO for USD 1 billion in direct aid Player Wins to support the agricultural industry and another USD 1 bil- lion to organize an agricultural recovery project in the occu- European Youth pied territories (Nagorno-Karabakh) of Azerbaijan once they’ve been liberated." Mammadguliyev said in an interview Championship with Russia’s state-run news agency RIA Novosti. Continued on page 2 CULTURE PAGE 11 Prepared for Georgia Today Business by Markets Asof26ͲAugͲ2016 STOCKS Price w/w m/m BONDS Price w/w m/m BankofGeorgia(BGEOLN) GBP28.57 +6,3% +5,9% GEOROG04/21 105.25(YTM5.46%) Ͳ +1,0% GHG(GHGLN) GBP2.55 Ͳ15,0% Ͳ18,4% -

Georgia Country Report

Informal Governance and Corruption – Transcending the Principal Agent and Collective Action Paradigms Georgia Country Report Alexander Kupatadze | July 2018 Basel Institute on Governance Steinenring 60 | 4051 Basel, Switzerland | +41 61 205 55 11 [email protected] | www.baselgovernance.org BASEL INSTITUTE ON GOVERNANCE This research has been funded by the UK government's Department for International Development (DFID) and the British Academy through the British Academy/DFID Anti-Corruption Evidence Programme. However, the views expressed do not necessarily reflect those of the British Academy or DFID. Dr Alexander Kupatadze, King's College London, Strand, London WC2R 2LS, United Kingdom, [email protected] 1 BASEL INSTITUTE ON GOVERNANCE Table of Contents Table of Contents 2 1 Introduction 3 1.1 Informal Governance and Corruption: Rationale and project background 3 1.2 Conceptual approach and methods 4 1.3 Informal governance in Georgia: clean public services coexist with collusive practices of elites 5 2 The Reform of the Georgian Public Registry 7 3 Evolution of state-business relations in Georgia: 9 3.1 The aftermath of the Rose Revolution: developmental patrimonialism or neoliberal economy? 10 3.2 Post-UNM era: continuity or change? 13 4 Ivanishvili and the personalised levers of informal power 15 4.1 Managing the blurred public/private divide: co-optation and control practices of the GD 16 4.2 Nepotism, cronyism and appointments in state bureaucracy: 19 5 Elections and informality in Georgia 20 6 Conclusions 22