CAUCASUS ANALYTICAL DIGEST No. 87, 23 September 2016 2

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

After a Summer of Protests, Can Georgia's Government Regain Its

Interview Published 23 September 2019 Originally published in World Politics Review By Olga Oliker, Crisis Group Program Director, Europe and Central Asia, and Olesya Vartanyan, Crisis Group Analyst, Eastern Neighbourhood After a Summer of Protests, Can Georgia’s Government Regain Its Lost Trust? This summer’s protests in Georgia led to changes to the country’s electoral system. But the country’s new Prime Minister, Giorgi Gakharia, is a man protesters wanted ousted from the last government, in which he led the Interior Ministry. In this interview with World Politics Review, Europe & Central Asia Program Director Olga Oliker and Analyst for EU Eastern Neighbourhood Olesya Vartanyan consider what Gakharia’s tenure will bring, and how the parliamentary elections next year might play out in this atmosphere. Earlier this month, Georgia’s Parliament more proportional representation, which the approved a new government led by Giorgi government agreed to. Protesters also subse- Gakharia, a controversial former interior minis- quently demanded that Gakharia step down ter who was nominated by the ruling Georgian as interior minister, a role from which he had Dream party despite his role in a violent crack- ordered the violent dispersal of the protests. down on anti-government protests that rocked But instead of being ousted, he was promoted to the capital, Tbilisi, this summer. Gakharia will prime minister, in a vote boycotted by opposi- now try to restore public confidence in the gov- tion parties. That’s a pretty clear message. ernment ahead of parliamentary elections that Gakharia’s appointment is also a mes- are expected to be held early next year. -

News Digest on Georgia

NEWS DIGEST ON GEORGIA September 9-11 Compiled by: Aleksandre Davitashvili Date: September 12, 2019 Occupied Regions Tskhinvali Region (so called South Ossetia) 1. Georgian FM, OSCE chair discuss situation along occupation line The Chair of the Organisation for Security and Co-operation in Europe (OSCE), Slovak Foreign Minister Miroslav Lajčák, met with the Georgian Foreign Minister David Zalkaliani earlier today. Particular attention was paid to the recent developments in two Russian occupied regions of Georgia: Abkhazia and Tskhinvali (South Ossetia) (Agenda.ge, September 10, 2019). 2. Gov‟t says occupying forces continue illegal works on Tbilisi-administered territory The Georgian State Security (SSS) says that the occupying forces are carrying out illegal works at two locations within Tbilisi-administered territory, near the village of Chorchana, in the Khashuri municipality. The agency reports that the European Union Monitoring mission (EUMM) and participants of the Geneva International Discussions will cooperate to address the problem (Agenda.ge, September 11, 2019). Foreign Affairs 3. Georgian clerics in David Gareji report construction of „two huge barracks‟ by Azerbaijan Georgian clerics in the 6th Century David Gareji monastery complex, which lies on the conditional border with Azerbaijan, have reported the construction of „two huge barracks by Azerbaijan right near the monastery complex.‟ “It is a sign that Azerbaijan has no plans to leave the territory of the monastery complex,” Archimandrite Kirion told local media. He stated that the number of Azerbaijani border guards has been increased to 70-80 since the beginning of the year and when the barracks are completed the number “is likely to reach 300.” Kirion says that Azerbaijan has provided electricity “from an 18 kilometer distance [for the barracks], and made an inscription on the rock of the Udabno Monastery that „death for the homeland is a big honor.” (Agenda.ge, September 9, 2019). -

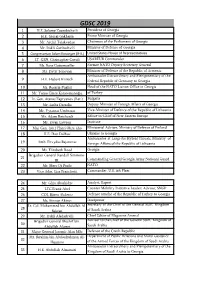

Gdsc 2019 1 H.E

GDSC 2019 1 H.E. Salome Zourabichvili President of Georgia 2 H.E. Giorgi Gakharia Prime Minister of Georgia 3 Mr. Archil Talakvadze Chairman of the Parliament of Georgia 4 Mr. Irakli Garibashvili Minister of Defence of Georgia 5 Congressman Adam Kinzinger (R-IL) United States House of Representatives 6 LT. GEN. Christopher Cavoli USAREUR Commander 7 Ms. Rose Gottemoeller Former NATO Deputy Secretary General 8 Mr. Davit Tonoyan Minister of Defence of the Republic of Armenia Ambassador Extraordinary and Plenipotentiary of the 9 H.E. Hubert Knirsch Federal Republic of Germany to Georgia 10 Ms. Rosaria Puglisi DeputyHead of Ministerthe NATO of LiaisonNational Office Defence in Georgia of the Republic 11 Mr. Yunus Emre Karaosmanoğlu Deputyof Turkey Minister of Defence of of the Republic of 12 Lt. Gen. Atanas Zapryanov (Ret.) Bulgaria 13 Mr. Lasha Darsalia Deputy Minister of Foreign Affairs of Georgia 14 Mr. Vytautas Umbrasas Vice-Minister of Defence of the Republic of Lithuania 15 Mr. Adam Reichardt SeniorEditor-in-Chief Research ofFellow, New EasternRoyal United Europe Services 16 Mr. Ewan Lawson Institute 17 Maj. Gen. (ret.) Harri Ohra-aho AmbassadorMinisterial Adviser, Extraordinary Ministry and of Plenipotentiary Defence of Finland of 18 H.E. Ihor Dolhov Ukraine to Georgia Ambassador-at-Large for Hybrid Threats, Ministry of 19 Amb. Eitvydas Bajarūnas ChargéForeign d’Affaires,Affairs of thea.i. Republicthe Embassy of Lithuania of the USA to 20 Ms. Elizabeth Rood Georgia Brigadier General Randall Simmons 21 JR. Director,Commanding Defense General Institution Georgia and Army Capacity National Building, Guard 22 Mr. Marc Di Paolo NATO 23 Vice Adm. -

THE FUTURE of BANKING «Over 70% of Georgia’S Residents Prefer to Pay with a Smartphone»

S GENERAL SPONSOR OF THE FORUM GOLDEN SPONSOR SPONSORS Media Partners PRIME ADS AD 30 April, 2018 News Making Money http://www.fi nchannel.com THE FUTURE OF BANKING «Over 70% of Georgia’s residents prefer to pay with a smartphone» well as customers have been During the last decade, the Igor Stepanov, forced to adapt. Mastercard development of smartphones Regional Director has made a number of im- has had a profound impact portant changes over the past on the way businesses oper- of Mastercard few years. Mastercard had to ate. With the percentage of overcome signifi cant chal- the global population using in Georgia and lenges to develop eff ective smartphones increasing ev- Central Asia digital tools that meet the dif- ery year, businesses are now fering needs of the countries expected to provide a fully it operates in. Also, by mod- integrated digital platform s the digitaliza- ernizing, particularly through that can provide diff erent tion process of digital services, banks cur- services. life faces sig- rently have an opportunity to nifi cant changes, diff erentiate themselves in a companies, as crowded market. A Continued on p. 4 Bank of Georgia Invests in Social Responsibility as Part of its Obligations See on p. 6 Why would we use crypto euros? See on p. 7 How DRC Carries out the Successful Resolution of Local and International Commercial Disputes See on p. 16 CARTU BANK: Strong Bank For Stronger Georgia See on p. 9 “Digitalization is the future of banks See on p. 10 CURRENCIES Bank of the future Apr 28 Apr 21 1 USD 2.4617 2.4402 is a bank oriented 1 EUR 2.9762 3.0017 100 RUB 3.9379 3.9729 on customers 1 TRY 0.6077 0.6036 See on p. -

Proverb As a Tool of Persuasion in Political Discourse (On the Material of Georgian and French Languages)

ISSN 1799-2591 Theory and Practice in Language Studies, Vol. 10, No. 6, pp. 632-637, June 2020 DOI: http://dx.doi.org/10.17507/tpls.1006.02 Proverb as a Tool of Persuasion in Political Discourse (on the Material of Georgian and French languages) Bela Glonti School of Arts and Sciences, Ilia State University, Tbilisi, Georgia; The Francophone Regional Doctoral College of Central and Eastern Europe in the Humanities (CODFREURCOR), Georgia Abstract—Our study deals with the use of proverbs as a tool of persuasion in political discourse. Within this study we have studied and analyzed the texts of Georgian and French political articles, speeches and proverbs used therein. The analysis revealed that the proverbs found and used by us in the French discourses were not only of French origin. Also, most of the proverbs found in the French discourses were used as titles of the articles. As for the Georgian proverbs, they consisted mainly of popular proverbs well known to the Georgian public. Georgia proverbs have rarely been cited as an article title. According to the general conclusion, the use of proverbs as a tool of persuasion in the political discourse by the politicians of both countries is quite relevant. It is effective when it is persuasive and at the same time causes an emotional reaction. Quoting the proverbs, the politicians base their thinking on positions. The proverb is one of the key argumentative techniques. Index Terms—proverb, translation, culture, argumentation I. INTRODUCTION The article is concerned with a proverb, as a tool of persuasion in Georgian and French political discourse. -

Vakhtang Gomelauri Minister of Internal Affairs, Government of Georgia Cc: Josep Borrell Fontelles, High Representative/Vice-Pre

Vakhtang Gomelauri Minister of Internal Affairs, Government of Georgia Cc: Josep Borrell Fontelles, High Representative/Vice-President of the Commission for Foreign Affairs and Security Policy Helena Dalli, Commissioner for Equality Carl Hartzell, Head of the EU Delegation to Georgia Brussels, 28 June 2021 Subject: Call on Georgian authorities to protect Tbilisi Pride protesters and ensure their universal right to freedom of expression and peaceful assembly are effectively enjoyed Dear Vakhtang Gomelauri, Minister of Internal Affairs, Government of Georgia, Between 1-5 July, Tbilisi will see its Pride march celebrations take place. These will include 3 main activities throughout the five days, including the official premiere of “March for Dignity”, a documentary about the first-ever Tbilisi Pride Week in 2019 (1 July), the Pride Fest with local and international artists (3 July) and the Pride “March for Dignity”, co-organized by local social movements (5 July). Collectively, these will constitute a major event where the diversity of the LGBTI community is celebrated and affirmed. Pride demonstrations are peaceful tools for political advocacy and one way in which the universal right to freedom of expression and peaceful assembly is crystallised. They are a hallmark of the LGBTI activist movement, a pillar for social visibility and they are equally political demonstrations during which the community voices its concerns, highlights its achievements and gives the opportunity to its members to demonstrate in favour of equality. As such, the recent comments of the Chair of the Ruling Georgian Dream Party, Irakli Kobakhidze, who said that the Pride March had to be cancelled, are in contravention of these universal rights and of the established precedent in Tbilisi. -

EUROPE a Albania • National Historical Museum – Tirana, Albania

EUROPE A Albania • National Historical Museum – Tirana, Albania o The country's largest museum. It was opened on 28 October 1981 and is 27,000 square meters in size, while 18,000 square meters are available for expositions. The National Historical Museum includes the following pavilions: Pavilion of Antiquity, Pavilion of the Middle Ages, Pavilion of Renaissance, Pavilion of Independence, Pavilion of Iconography, Pavilion of the National Liberation Antifascist War, Pavilion of Communist Terror, and Pavilion of Mother Teresa. • Et'hem Bey Mosque – Tirana, Albania o The Et’hem Bey Mosque is located in the center of the Albanian capital Tirana. Construction was started in 1789 by Molla Bey and it was finished in 1823 by his son Ethem Pasha (Haxhi Ethem Bey), great- grandson of Sulejman Pasha. • Mount Dajt – Tirana, Albania o Its highest peak is at 1,613 m. In winter, the mountain is often covered with snow, and it is a popular retreat to the local population of Tirana that rarely sees snow falls. Its slopes have forests of pines, oak and beech. Dajti Mountain was declared a National Park in 1966, and has since 2006 an expanded area of about 29,384 ha. It is under the jurisdiction and administration of Tirana Forest Service Department. • Skanderbeg Square – Tirana, Albania o Skanderbeg Square is the main plaza of Tirana, Albania named in 1968 after the Albanian national hero Skanderbeg. A Skanderbeg Monument can be found in the plaza. • Skanderbeg Monument – Skanderberg Square, Tirana, Albania o The monument in memory of Skanderbeg was erected in Skanderbeg Square, Tirana. -

Opposition United National Movement Party Enters Georgian Parliament

“Impartial, Informative, Insightful” GEL 3.00 #104 (4908) TUESDAY, JUNE 1, 2021 WWW.MESSENGER.COM.GE Opposition United National Movement party enters Georgian Parliament BY VERONIKA MALINBOYM numerous occasions that the reason why political agreement, which is the basis for many priorities. This is important work the party refuses to sign the agreement consensus for ending the political crisis.” that needs the responsible participation of eorgia’s major opposition United proposed by the President of the Euro- Meanwhile, the US and EU ambassa- all of Georgia’s elected leaders. By signing G National Movement party will enter pean Council Charles Michel is because dors to Georgia expressed strong regret this agreement the UNM would demon- the parliament after a six-month boycott, of the amnesty that it extended upon the overy the UNM’s refusal to sign the EU- strate its commitment to carry out these chairman of the party, Nika Melia has party’s leader Nika Melia, stating that mediated agreement: fundamental objectives in the interest of announced. Melia added that despite its amnesty implies some sort of guilt, while "However, we strongly regret that the Georgia, its citizens, EU-Georgia relations decision, the United National Movement Nika Melia was just a political prisoner. United National Movement did not seize and Georgia’s Euro-Atlantic future," read party will still refrain from signing the The ruling Georgian Dream party the opportunity today to join the other par- the official statement reads. EU-brokered agreement between the also commented on the United National ties in signing the 19 April agreement. -

The Current State of Housing in Tbilisi and Yerevan: a Brief Primer 8 Joseph Salukvadze, Tbilisi

Research Collection Journal Issue Cities in the South Caucasus Author(s): Petrosyan, Sarhat; Valiyev, Anar; Salukvadze, Joseph Publication Date: 2016-09-23 Permanent Link: https://doi.org/10.3929/ethz-a-010819028 Rights / License: In Copyright - Non-Commercial Use Permitted This page was generated automatically upon download from the ETH Zurich Research Collection. For more information please consult the Terms of use. ETH Library No. 87 23 September 2016 Abkhazia South Ossetia caucasus Adjara analytical digest Nagorno- Karabakh www.laender-analysen.de/cad www.css.ethz.ch/en/publications/cad.html CITIES IN THE SOUTH CAUCASUS Special Editor: David Sichinava, Tbilisi State University | Fulbright Visiting Scholar at CU Boulder ■■The Transformation of Yerevan’s Urban Landscape After Independence 2 Sarhat Petrosyan, Yerevan ■■Urban Development Baku: From Soviet Past To Modern Future 5 Anar Valiyev, Baku ■■The Current State of Housing in Tbilisi and Yerevan: a Brief Primer 8 Joseph Salukvadze, Tbilisi ■■CHRONICLE From 22 July to 20 September 2016 12 This special issue is funded by the Academic Swiss Caucasus Network (ASCN). Research Centre Center Caucasus Research German Association for for East European Studies for Security Studies Resource Centers East European Studies University of Bremen ETH Zurich CAUCASUS ANALYTICAL DIGEST No. 87, 23 September 2016 2 The Transformation of Yerevan’s Urban Landscape After Independence Sarhat Petrosyan, Yerevan Abstract Like most of the world’s cities, Yerevan’s landscape has changed dramatically over the past 25 years, partic- ularly as a result of post-soviet Armenia’s sociopolitical shifts. Although these urban transformations have been and continue to be widely discussed in the local media, there is insufficient research and writing on this process and its circumstances. -

University of California

UCLA UCLA Electronic Theses and Dissertations Title The Calouste Gulbenkian Library, Armenian Patriarchate of Jerusalem, 1925-1990: An Historical Portrait of a Monastic and Lay Community Intellectual Resource Center Permalink https://escholarship.org/uc/item/8f39k3ht Author Manoogian, Sylva Natalie Publication Date 2012 Supplemental Material https://escholarship.org/uc/item/8f39k3ht#supplemental Peer reviewed|Thesis/dissertation eScholarship.org Powered by the California Digital Library University of California UNIVERSITY OF CALIFORNIA Los Angeles The Calouste Gulbenkian Library, Armenian Patriarchate of Jerusalem, 1925-1990: An Historical Portrait of a Monastic and Lay Community Intellectual Resource Center A dissertation submitted in partial satisfaction of the requirements for the degree Doctor of Philosophy in Library and Information Science by Sylva Natalie Manoogian 2013 ABSTRACT OF THE DISSERTATION The Calouste Gulbenkian Library, Armenian Patriarchate of Jerusalem, 1925-1990: An Historical Portrait of a Monastic and Lay Community Intellectual Resource Center by Sylva Natalie Manoogian Doctor of Philosophy in Library and Information Science University of California, Los Angeles 2013 Professor Mary Niles Maack, Chair The Armenian Patriarchate of Jerusalem is a major religious, educational, cultural, and ecumenical institution, established more than fourteen centuries ago. The Calouste Gulbenkian Library is one of the Patriarchate’s five intellectual resource centers. Plans for its establishment began in 1925 as a tribute to Patriarch Yeghishe I Tourian to commemorate the 50th anniversary of his ordination to the priesthood. Its primary mission has been to collect and preserve valuable works of Armenian religion, language, art, literature, and history, as well as representative works of world literature in a number of languages. -

1 Building Narratives Into Gyumri: an Engineer's Tale by Gayane

Building Narratives into Gyumri: An Engineer’s Tale by Gayane Aghabalyan Presented to the Department of English & Communications in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Bachelor of Arts American University of Armenia Yerevan, Armenia May 12, 2020 1 Table of Contents Abstract 3 Acknowledgements 4 Introduction 7 Literature review 10 Research question 13 Methodology 13 Building narratives into Gyumri: An engineer’s tale 14 The Railway Station of Gyumri – An entry point to the city and the highest point of my grandfather’s career 15 The Polytechnic Institute – A mistake that cost lives of many students 19 The Black Fountain, Kumayri Tour Center and Shirak Hotel – It was the people not the earthquake 24 The creative aspect of the research 30 Limitations and avenues for further research 35 Epilogue 35 References 37 Appendices 39 2 Abstract This research studies the relationship between an engineer and his buildings. It aims to unravel how his recollections of the past and the desires for the future stay implanted in these structures. The study is done through a set of oral history interviews with my grandfather who worked as an engineer for over 45 years in Gyumri and has built and led the construction of numerous buildings. This capstone concentrates on five specific sites – Gyumri Railway Station, National Polytechnic University of Armenia Leninakan Branch, Black Fountain, Kumayri Tour Center and Shirak Hotel. Each of these places have gained new meanings for my grandfather and have become symbols and milestones both in his personal narrative and the collective and cultural history of Gyumri. -

Georgia's Anti-Corruption Policy in the Context of Eu Association Process

SMALL STEPS TOWARDS BIG GOALS: GEORGIA’S ANTI-CORRUPTION POLICY IN THE CONTEXT OF EU ASSOCIATION PROCESS JUNE 2019 The publication was prepared with the financial support of Swedish International Development Cooperation Agency (SIDA). Transparency International Georgia is responsible for the content of the publication. It might not necessarily reflect the views of SIDA. EXECUTIVE SUMMARY The Association Agreement between the European Union and Georgia, as well as the Association Agenda for 2017-2020 approved by the parties to facilitate the implementation of the Association Agreement, provide for cooperation between the parties in combating corruption, while highlighting Georgia’s commitment to address corruption, in particular complex corruption. Over the year and a half since the adoption of the current Association Agenda, Georgia has attained positive results in terms of maintaining previous achievements in terms of eradicating petty corruption. However, Georgia’s progress in tackling high-level corruption remains weak. According to public opinion surveys, citizens have a negative view of both the overall situation in the country in terms of corruption and the dynamics of this situation. They believe that the government does not effectively investigate the cases of corruption involving high-ranking officials or influential individuals with ties to the ruling party. Such public attitudes evidently stem from the ineffective response of the law enforcement agencies to recent high-profile cases of alleged corruption related to a variety