Georgia Country Report

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Lids for Kids™

Ben & Jerry's® And Yahoo!® Help Connect Schools To The Internet Back To School With Lids For Kids™ S. Burlington, VT & Santa Clara, Calif. -- August 25, 1997 -- Ben & Jerry's Homemade Inc., manufacturer of super premium frozen desserts, and Yahoo!, Inc. (http://www.yahoo.com), the leading Internet guide, have teamed up to help schools get connected to the Internet through a dynamic consumer sweepstakes promotion. Dubbed "Lids for Kids™", the national sweepstakes invites individuals to send in lids from pints of Ben & Jerry's products to support NetDay, a grassroots volunteer initiative to help K-12 schools in the United States connect to the Internet. "NetDay is not just about making the wire connections that make network and Internet access a reality," said Michael Kaufman of PBS, and co-founder of NetDay. "We're making and strengthening the connections between people, both inside and outside the classroom, who share a common goal: to provide the best possible education for our children. NetDay is pleased to partner with Ben & Jerry's and Yahoo! to help make that goal a reality." Launching today, the "Lids for Kids™" sweepstakes offers individuals a chance to help NetDay and win from more than 25,000 prizes for sending in lids from pints of Ben & Jerry's ice cream, low fat ice cream, frozen yogurt, and sorbet -- the grand prize being a lifetime supply of Ben & Jerry's. For every lid collected, Yahoo! and Ben & Jerry's will contribute ten cents to NetDay -- with a goal of $100,000. "Since we started the company, Yahoo! has been dedicated to promoting community awareness through outreach, education, and information access," said David Filo, co-founder and chief Yahoo at Yahoo!. -

Georgia's October 2013 Presidential Election: Outcome and Implications

Georgia’s October 2013 Presidential Election: Outcome and Implications Jim Nichol Specialist in Russian and Eurasian Affairs November 4, 2013 Congressional Research Service 7-5700 www.crs.gov R43299 Georgia’s October 2013 Presidential Election: Outcome and Implications Summary This report discusses Georgia’s October 27, 2013, presidential election and its implications for U.S. interests. The election took place one year after a legislative election that witnessed the mostly peaceful shift of legislative and ministerial power from the ruling party, the United National Movement (UNM), to the Georgia Dream (GD) coalition bloc. The newly elected president, Giorgi Margvelashvili of the GD, will have fewer powers under recently approved constitutional changes. Most observers have viewed the 2013 presidential election as marking Georgia’s further progress in democratization, including a peaceful shift of presidential power from UNM head Mikheil Saakashvili to GD official Margvelashvili. Some analysts, however, have raised concerns over ongoing tensions between the UNM and GD, as well as Prime Minister and GD head Bidzini Ivanishvili’s announcement on November 2, 2013, that he will step down as the premier. In his victory speech on October 28, Margvelashvili reaffirmed Georgia’s Euro-Atlantic foreign policy orientation, including the pursuit of Georgia’s future membership in NATO and the EU. At the same time, he reiterated that GD would continue to pursue the normalization of ties with Russia. On October 28, 2013, the U.S. State Department praised the Georgian presidential election as generally democratic and expressing the will of the people, and as demonstrating Georgia’s continuing commitment to Euro-Atlantic integration. -

After a Summer of Protests, Can Georgia's Government Regain Its

Interview Published 23 September 2019 Originally published in World Politics Review By Olga Oliker, Crisis Group Program Director, Europe and Central Asia, and Olesya Vartanyan, Crisis Group Analyst, Eastern Neighbourhood After a Summer of Protests, Can Georgia’s Government Regain Its Lost Trust? This summer’s protests in Georgia led to changes to the country’s electoral system. But the country’s new Prime Minister, Giorgi Gakharia, is a man protesters wanted ousted from the last government, in which he led the Interior Ministry. In this interview with World Politics Review, Europe & Central Asia Program Director Olga Oliker and Analyst for EU Eastern Neighbourhood Olesya Vartanyan consider what Gakharia’s tenure will bring, and how the parliamentary elections next year might play out in this atmosphere. Earlier this month, Georgia’s Parliament more proportional representation, which the approved a new government led by Giorgi government agreed to. Protesters also subse- Gakharia, a controversial former interior minis- quently demanded that Gakharia step down ter who was nominated by the ruling Georgian as interior minister, a role from which he had Dream party despite his role in a violent crack- ordered the violent dispersal of the protests. down on anti-government protests that rocked But instead of being ousted, he was promoted to the capital, Tbilisi, this summer. Gakharia will prime minister, in a vote boycotted by opposi- now try to restore public confidence in the gov- tion parties. That’s a pretty clear message. ernment ahead of parliamentary elections that Gakharia’s appointment is also a mes- are expected to be held early next year. -

News Digest on Georgia

NEWS DIGEST ON GEORGIA May 13-15 Compiled by: Aleksandre Davitashvili Date: May 16, 2019 Foreign Affairs 1. Georgia negotiating with Germany, France, Poland, Israel on legal employment Georgia is negotiating with three EU member states, Germany, France and Poland to allow for the legal employment of Georgians in those countries, as well as with Israel, the Ministry of Foreign Affairs of Georgia reports. An agreement has already been achieved with France. ―Legal employment of Georgians is one of the priorities for the ministry of Foreign Affairs, as such deals will decrease the number of illegal migrants and boost the qualification of Georgian nationals,‖ the Foreign Ministry says. A pilot project is underway with Poland, with up to 45 Georgian citizens legally employed, the ministry says (Agenda.ge, May 13, 2019). 2. Georgia elected as United Nations Statistical Commission member for 2020-2023 Georgia was unanimously elected as a member of the United Nations Statistical Commission (UNSC) for a period of four years, announces the National Statistics Office of Georgia (Geostat). The membership mandate will span from 2020-2023. A total of eight new members of the UNSC were elected for the same period on May 7 in New York at the meeting of the United Nations Economic and Social Council (ECOSOC) (Agenda.ge, May 14, 2019). 3. President of European Commission Tusk: 10 years on there is more Armenia, Azerbaijan, Belarus, Georgia, Moldova, Ukraine in EU President of the European Commission Donald Tusk stated on the 10th anniversary of the EU‘s Eastern Partnership format that there is more Armenia, Azerbaijan, Belarus, Georgia, Moldova and Ukraine in the EU. -

News Digest on Georgia

NEWS DIGEST ON GEORGIA September 9-11 Compiled by: Aleksandre Davitashvili Date: September 12, 2019 Occupied Regions Tskhinvali Region (so called South Ossetia) 1. Georgian FM, OSCE chair discuss situation along occupation line The Chair of the Organisation for Security and Co-operation in Europe (OSCE), Slovak Foreign Minister Miroslav Lajčák, met with the Georgian Foreign Minister David Zalkaliani earlier today. Particular attention was paid to the recent developments in two Russian occupied regions of Georgia: Abkhazia and Tskhinvali (South Ossetia) (Agenda.ge, September 10, 2019). 2. Gov‟t says occupying forces continue illegal works on Tbilisi-administered territory The Georgian State Security (SSS) says that the occupying forces are carrying out illegal works at two locations within Tbilisi-administered territory, near the village of Chorchana, in the Khashuri municipality. The agency reports that the European Union Monitoring mission (EUMM) and participants of the Geneva International Discussions will cooperate to address the problem (Agenda.ge, September 11, 2019). Foreign Affairs 3. Georgian clerics in David Gareji report construction of „two huge barracks‟ by Azerbaijan Georgian clerics in the 6th Century David Gareji monastery complex, which lies on the conditional border with Azerbaijan, have reported the construction of „two huge barracks by Azerbaijan right near the monastery complex.‟ “It is a sign that Azerbaijan has no plans to leave the territory of the monastery complex,” Archimandrite Kirion told local media. He stated that the number of Azerbaijani border guards has been increased to 70-80 since the beginning of the year and when the barracks are completed the number “is likely to reach 300.” Kirion says that Azerbaijan has provided electricity “from an 18 kilometer distance [for the barracks], and made an inscription on the rock of the Udabno Monastery that „death for the homeland is a big honor.” (Agenda.ge, September 9, 2019). -

News Digest on Georgia

NEWS DIGEST ON GEORGIA July 13-16 Compiled by: Aleksandre Davitashvili Date: July 17, 2018 Occupied Regions Abkhazia Region 1. Saakashvili, Akhalaia, Kezerashvili, Okruashvili included in black list of occupied Abkhazia The "Organization of War Veterans" of occupied Abkhazia has presented “Khishba-Sigua List” to the de-facto parliament of Abkhazia. The following persons are included in the list set up in response to Georgian central government’s so-called “Otkhozoria-Tatunashvili List” : Ex-president Mikheil Saakashvili, former defence ministers – Bacho Akhalaia, Davit Kezerashvili, Irakli Okruashvili, Tengiz Kitovani and Gia Karkarashvili, former secretary of the National Security Council Irakli Batiashvili, former internal affairs minister Vano Merabishvili, Former head of the Joint Staff of the Georgian Armed Forces Zaza Gogava, former Defense Ministry senior official Megis Kardava, Brigadier General Mamuka Kurashvili, leader of "Forest Brothers" Davit Shengelia, former employee of the MIA Roman Shamatava and other persons are included in the list (IPN.GE, July 15, 2018). 2. Sergi Kapanadze says “Khishba-Sigua List” by de-facto Abkhazia is part of internal game and means nothing for Georgia There is no need to make a serious comment about “Khishba-Sigua List” as this list cannot have any effect on the public life of Georgia, Sergi Kapanadze, member of the “European Georgia” party, told reporters. The lawmaker believes that the list will not have legal or political consequences. (IPN.GE, July 15, 2018). Foreign Affairs 3. Jens Stoltenberg – We agreed to continue working together to prepare Georgia for NATO membership “We also met with the Presidents of Georgia and Ukraine. Together we discussed shared concerns. -

Quarterly Report on the Political Situation in Georgia and Related Foreign Malign Influence

REPORT QUARTERLY REPORT ON THE POLITICAL SITUATION IN GEORGIA AND RELATED FOREIGN MALIGN INFLUENCE 2021 EUROPEAN VALUES CENTER FOR SECURITY POLICY European Values Center for Security Policy is a non-governmental, non-partisan institute defending freedom and sovereignty. We protect liberal democracy, the rule of law, and the transatlantic alliance of the Czech Republic. We help defend Europe especially from the malign influences of Russia, China, and Islamic extremists. We envision a free, safe, and prosperous Czechia within a vibrant Central Europe that is an integral part of the transatlantic community and is based on a firm alliance with the USA. Authors: David Stulík - Head of Eastern European Program, European Values Center for Security Policy Miranda Betchvaia - Intern of Eastern European Program, European Values Center for Security Policy Notice: The following report (ISSUE 3) aims to provide a brief overview of the political crisis in Georgia and its development during the period of January-March 2021. The crisis has been evolving since the parliamentary elections held on 31 October 2020. The report briefly summarizes the background context, touches upon the current political deadlock, and includes the key developments since the previous quarterly report. Responses from the third sector and Georgia’s Western partners will also be discussed. Besides, the report considers anti-Western messages and disinformation, which have contributed to Georgia’s political crisis. This report has been produced under the two-years project implemented by the Prague-based European Values Center for Security Policy in Georgia. The project is supported by the Transition Promotion Program of The Czech Ministry of Foreign Affairs and the Emerging Donors Challenge Program of the USAID. -

Georgia: Background and U.S

Georgia: Background and U.S. Policy Updated September 5, 2018 Congressional Research Service https://crsreports.congress.gov R45307 SUMMARY R45307 Georgia: Background and U.S. Policy September 5, 2018 Georgia is one of the United States’ closest non-NATO partners among the post-Soviet states. With a history of strong economic aid and security cooperation, the United States Cory Welt has deepened its strategic partnership with Georgia since Russia’s 2008 invasion of Analyst in European Affairs Georgia and 2014 invasion of Ukraine. U.S. policy expressly supports Georgia’s sovereignty and territorial integrity within its internationally recognized borders, and Georgia is a leading recipient of U.S. aid in Europe and Eurasia. Many observers consider Georgia to be one of the most democratic states in the post-Soviet region, even as the country faces ongoing governance challenges. The center-left Georgian Dream party has more than a three-fourths supermajority in parliament, allowing it to rule with only limited checks and balances. Although Georgia faces high rates of poverty and underemployment, its economy in 2017 appeared to enter a period of stronger growth than the previous four years. The Georgian Dream won elections in 2012 amid growing dissatisfaction with the former ruling party, Georgia: Basic Facts Mikheil Saakashvili’s center-right United National Population: 3.73 million (2018 est.) Movement, which came to power as a result of Comparative Area: slightly larger than West Virginia Georgia’s 2003 Rose Revolution. In August 2008, Capital: Tbilisi Russia went to war with Georgia to prevent Ethnic Composition: 87% Georgian, 6% Azerbaijani, 5% Saakashvili’s government from reestablishing control Armenian (2014 census) over Georgia’s regions of South Ossetia and Abkhazia, Religion: 83% Georgian Orthodox, 11% Muslim, 3% Armenian which broke away from Georgia in the early 1990s to Apostolic (2014 census) become informal Russian protectorates. -

Georgia Between Dominant-Power Politics, Feckless Pluralism, and Democracy Christofer Berglund Uppsala University

GEORGIA BETWEEN DOMINANT-POWER POLITICS, FECKLESS PLURALISM, AND DEMOCRACY CHRISTOFER BERGLUND UPPSALA UNIVERSITY Abstract: This article charts the last decade of Georgian politics (2003-2013) through theories of semi- authoritarianism and democratization. It first dissects Saakashvili’s system of dominant-power politics, which enabled state-building reforms, yet atrophied political competition. It then analyzes the nested two-level game between incumbents and opposition in the run-up to the 2012 parliamentary elections. After detailing the verdict of Election Day, the article turns to the tense cohabitation that next pushed Georgia in the direction of feckless pluralism. The last section examines if the new ruling party is taking Georgia in the direction of democratic reforms or authoritarian closure. nder what conditions do elections in semi-authoritarian states spur Udemocratic breakthroughs?1 This is a conundrum relevant to many hybrid regimes in the region of the former Soviet Union. It is also a ques- tion of particular importance for the citizens of Georgia, who surprisingly voted out the United National Movement (UNM) and instead backed the Georgian Dream (GD), both in the October 2012 parliamentary elections and in the October 2013 presidential elections. This article aims to shed light on the dramatic, but not necessarily democratic, political changes unleashed by these events. It is, however, beneficial to first consult some of the concepts and insights that have been generated by earlier research on 1 The author is grateful to Sten Berglund, Ketevan Bolkvadze, Selt Hasön, and participants at the 5th East Asian Conference on Slavic-Eurasian Studies, as well as the anonymous re- viewers, for their useful feedback. -

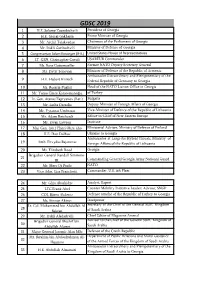

Gdsc 2019 1 H.E

GDSC 2019 1 H.E. Salome Zourabichvili President of Georgia 2 H.E. Giorgi Gakharia Prime Minister of Georgia 3 Mr. Archil Talakvadze Chairman of the Parliament of Georgia 4 Mr. Irakli Garibashvili Minister of Defence of Georgia 5 Congressman Adam Kinzinger (R-IL) United States House of Representatives 6 LT. GEN. Christopher Cavoli USAREUR Commander 7 Ms. Rose Gottemoeller Former NATO Deputy Secretary General 8 Mr. Davit Tonoyan Minister of Defence of the Republic of Armenia Ambassador Extraordinary and Plenipotentiary of the 9 H.E. Hubert Knirsch Federal Republic of Germany to Georgia 10 Ms. Rosaria Puglisi DeputyHead of Ministerthe NATO of LiaisonNational Office Defence in Georgia of the Republic 11 Mr. Yunus Emre Karaosmanoğlu Deputyof Turkey Minister of Defence of of the Republic of 12 Lt. Gen. Atanas Zapryanov (Ret.) Bulgaria 13 Mr. Lasha Darsalia Deputy Minister of Foreign Affairs of Georgia 14 Mr. Vytautas Umbrasas Vice-Minister of Defence of the Republic of Lithuania 15 Mr. Adam Reichardt SeniorEditor-in-Chief Research ofFellow, New EasternRoyal United Europe Services 16 Mr. Ewan Lawson Institute 17 Maj. Gen. (ret.) Harri Ohra-aho AmbassadorMinisterial Adviser, Extraordinary Ministry and of Plenipotentiary Defence of Finland of 18 H.E. Ihor Dolhov Ukraine to Georgia Ambassador-at-Large for Hybrid Threats, Ministry of 19 Amb. Eitvydas Bajarūnas ChargéForeign d’Affaires,Affairs of thea.i. Republicthe Embassy of Lithuania of the USA to 20 Ms. Elizabeth Rood Georgia Brigadier General Randall Simmons 21 JR. Director,Commanding Defense General Institution Georgia and Army Capacity National Building, Guard 22 Mr. Marc Di Paolo NATO 23 Vice Adm. -

Proverb As a Tool of Persuasion in Political Discourse (On the Material of Georgian and French Languages)

ISSN 1799-2591 Theory and Practice in Language Studies, Vol. 10, No. 6, pp. 632-637, June 2020 DOI: http://dx.doi.org/10.17507/tpls.1006.02 Proverb as a Tool of Persuasion in Political Discourse (on the Material of Georgian and French languages) Bela Glonti School of Arts and Sciences, Ilia State University, Tbilisi, Georgia; The Francophone Regional Doctoral College of Central and Eastern Europe in the Humanities (CODFREURCOR), Georgia Abstract—Our study deals with the use of proverbs as a tool of persuasion in political discourse. Within this study we have studied and analyzed the texts of Georgian and French political articles, speeches and proverbs used therein. The analysis revealed that the proverbs found and used by us in the French discourses were not only of French origin. Also, most of the proverbs found in the French discourses were used as titles of the articles. As for the Georgian proverbs, they consisted mainly of popular proverbs well known to the Georgian public. Georgia proverbs have rarely been cited as an article title. According to the general conclusion, the use of proverbs as a tool of persuasion in the political discourse by the politicians of both countries is quite relevant. It is effective when it is persuasive and at the same time causes an emotional reaction. Quoting the proverbs, the politicians base their thinking on positions. The proverb is one of the key argumentative techniques. Index Terms—proverb, translation, culture, argumentation I. INTRODUCTION The article is concerned with a proverb, as a tool of persuasion in Georgian and French political discourse. -

OTR Newsletter

OFFICIAL NEWSLETTER OF TAMPA INTERNATIONAL AIRPORT ontheRADAR SEPTEMBER 2016 Blue Arrivals/ Departures curbsides to close nightly due to construction Beginning Sept. 6 through early 2017, Tampa the new rental car center with the Main Terminal. During International Airport will close the blue side arrival this process, there can be no activity underneath. and departure curbsides from 8 p.m. to 4 a.m. for construction of the SkyConnect guideway. The Airport will dry-run the closures the nights of Sept. 6 and 7 and make any necessary changes to plans to This closure affects passengers on American, Delta, ensure smooth traffic flow, as is typically done with all JetBlue and United. During this time, all pick-ups and construction likely to impact passengers. Construction drop-offs for those airlines will be directed to Short is scheduled to begin the night of September 8. n Term Parking. Other ground transportation options, including taxis and hotel shuttles, will not be affected. • Guests should park in the Short Term Parking garage and take the blue elevators to baggage claim to meet their travelers. Parking fees will be waived for drop-offs and pick-ups. • Crews will temporarily stop work and operations will return to normal during the Thanksgiving and winter holidays, as well as the National College Football Championship in January. • Drivers are asked to closely observe all posted speed limits and watch for directional signage. The closures are necessary to ensure the safety of guests, employees and tenants while crews lift steel beams that The Airport will close the roadways in front of Blue Arrivals and Departures weight up to 146,000 pounds – about the weight of a to allow for steel beams, some weighing as much as 146,000 pounds, to Boeing 737-700 – and pour concrete over the roadways be placed into position on the SkyConnect Guideway.