Georgia National Integrity System Assessment 2020

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

After a Summer of Protests, Can Georgia's Government Regain Its

Interview Published 23 September 2019 Originally published in World Politics Review By Olga Oliker, Crisis Group Program Director, Europe and Central Asia, and Olesya Vartanyan, Crisis Group Analyst, Eastern Neighbourhood After a Summer of Protests, Can Georgia’s Government Regain Its Lost Trust? This summer’s protests in Georgia led to changes to the country’s electoral system. But the country’s new Prime Minister, Giorgi Gakharia, is a man protesters wanted ousted from the last government, in which he led the Interior Ministry. In this interview with World Politics Review, Europe & Central Asia Program Director Olga Oliker and Analyst for EU Eastern Neighbourhood Olesya Vartanyan consider what Gakharia’s tenure will bring, and how the parliamentary elections next year might play out in this atmosphere. Earlier this month, Georgia’s Parliament more proportional representation, which the approved a new government led by Giorgi government agreed to. Protesters also subse- Gakharia, a controversial former interior minis- quently demanded that Gakharia step down ter who was nominated by the ruling Georgian as interior minister, a role from which he had Dream party despite his role in a violent crack- ordered the violent dispersal of the protests. down on anti-government protests that rocked But instead of being ousted, he was promoted to the capital, Tbilisi, this summer. Gakharia will prime minister, in a vote boycotted by opposi- now try to restore public confidence in the gov- tion parties. That’s a pretty clear message. ernment ahead of parliamentary elections that Gakharia’s appointment is also a mes- are expected to be held early next year. -

News Digest on Georgia

NEWS DIGEST ON GEORGIA September 9-11 Compiled by: Aleksandre Davitashvili Date: September 12, 2019 Occupied Regions Tskhinvali Region (so called South Ossetia) 1. Georgian FM, OSCE chair discuss situation along occupation line The Chair of the Organisation for Security and Co-operation in Europe (OSCE), Slovak Foreign Minister Miroslav Lajčák, met with the Georgian Foreign Minister David Zalkaliani earlier today. Particular attention was paid to the recent developments in two Russian occupied regions of Georgia: Abkhazia and Tskhinvali (South Ossetia) (Agenda.ge, September 10, 2019). 2. Gov‟t says occupying forces continue illegal works on Tbilisi-administered territory The Georgian State Security (SSS) says that the occupying forces are carrying out illegal works at two locations within Tbilisi-administered territory, near the village of Chorchana, in the Khashuri municipality. The agency reports that the European Union Monitoring mission (EUMM) and participants of the Geneva International Discussions will cooperate to address the problem (Agenda.ge, September 11, 2019). Foreign Affairs 3. Georgian clerics in David Gareji report construction of „two huge barracks‟ by Azerbaijan Georgian clerics in the 6th Century David Gareji monastery complex, which lies on the conditional border with Azerbaijan, have reported the construction of „two huge barracks by Azerbaijan right near the monastery complex.‟ “It is a sign that Azerbaijan has no plans to leave the territory of the monastery complex,” Archimandrite Kirion told local media. He stated that the number of Azerbaijani border guards has been increased to 70-80 since the beginning of the year and when the barracks are completed the number “is likely to reach 300.” Kirion says that Azerbaijan has provided electricity “from an 18 kilometer distance [for the barracks], and made an inscription on the rock of the Udabno Monastery that „death for the homeland is a big honor.” (Agenda.ge, September 9, 2019). -

News Digest on Georgia

NEWS DIGEST ON GEORGIA July 13-16 Compiled by: Aleksandre Davitashvili Date: July 17, 2018 Occupied Regions Abkhazia Region 1. Saakashvili, Akhalaia, Kezerashvili, Okruashvili included in black list of occupied Abkhazia The "Organization of War Veterans" of occupied Abkhazia has presented “Khishba-Sigua List” to the de-facto parliament of Abkhazia. The following persons are included in the list set up in response to Georgian central government’s so-called “Otkhozoria-Tatunashvili List” : Ex-president Mikheil Saakashvili, former defence ministers – Bacho Akhalaia, Davit Kezerashvili, Irakli Okruashvili, Tengiz Kitovani and Gia Karkarashvili, former secretary of the National Security Council Irakli Batiashvili, former internal affairs minister Vano Merabishvili, Former head of the Joint Staff of the Georgian Armed Forces Zaza Gogava, former Defense Ministry senior official Megis Kardava, Brigadier General Mamuka Kurashvili, leader of "Forest Brothers" Davit Shengelia, former employee of the MIA Roman Shamatava and other persons are included in the list (IPN.GE, July 15, 2018). 2. Sergi Kapanadze says “Khishba-Sigua List” by de-facto Abkhazia is part of internal game and means nothing for Georgia There is no need to make a serious comment about “Khishba-Sigua List” as this list cannot have any effect on the public life of Georgia, Sergi Kapanadze, member of the “European Georgia” party, told reporters. The lawmaker believes that the list will not have legal or political consequences. (IPN.GE, July 15, 2018). Foreign Affairs 3. Jens Stoltenberg – We agreed to continue working together to prepare Georgia for NATO membership “We also met with the Presidents of Georgia and Ukraine. Together we discussed shared concerns. -

Georgia Between Dominant-Power Politics, Feckless Pluralism, and Democracy Christofer Berglund Uppsala University

GEORGIA BETWEEN DOMINANT-POWER POLITICS, FECKLESS PLURALISM, AND DEMOCRACY CHRISTOFER BERGLUND UPPSALA UNIVERSITY Abstract: This article charts the last decade of Georgian politics (2003-2013) through theories of semi- authoritarianism and democratization. It first dissects Saakashvili’s system of dominant-power politics, which enabled state-building reforms, yet atrophied political competition. It then analyzes the nested two-level game between incumbents and opposition in the run-up to the 2012 parliamentary elections. After detailing the verdict of Election Day, the article turns to the tense cohabitation that next pushed Georgia in the direction of feckless pluralism. The last section examines if the new ruling party is taking Georgia in the direction of democratic reforms or authoritarian closure. nder what conditions do elections in semi-authoritarian states spur Udemocratic breakthroughs?1 This is a conundrum relevant to many hybrid regimes in the region of the former Soviet Union. It is also a ques- tion of particular importance for the citizens of Georgia, who surprisingly voted out the United National Movement (UNM) and instead backed the Georgian Dream (GD), both in the October 2012 parliamentary elections and in the October 2013 presidential elections. This article aims to shed light on the dramatic, but not necessarily democratic, political changes unleashed by these events. It is, however, beneficial to first consult some of the concepts and insights that have been generated by earlier research on 1 The author is grateful to Sten Berglund, Ketevan Bolkvadze, Selt Hasön, and participants at the 5th East Asian Conference on Slavic-Eurasian Studies, as well as the anonymous re- viewers, for their useful feedback. -

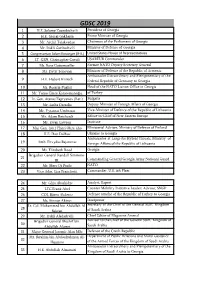

Gdsc 2019 1 H.E

GDSC 2019 1 H.E. Salome Zourabichvili President of Georgia 2 H.E. Giorgi Gakharia Prime Minister of Georgia 3 Mr. Archil Talakvadze Chairman of the Parliament of Georgia 4 Mr. Irakli Garibashvili Minister of Defence of Georgia 5 Congressman Adam Kinzinger (R-IL) United States House of Representatives 6 LT. GEN. Christopher Cavoli USAREUR Commander 7 Ms. Rose Gottemoeller Former NATO Deputy Secretary General 8 Mr. Davit Tonoyan Minister of Defence of the Republic of Armenia Ambassador Extraordinary and Plenipotentiary of the 9 H.E. Hubert Knirsch Federal Republic of Germany to Georgia 10 Ms. Rosaria Puglisi DeputyHead of Ministerthe NATO of LiaisonNational Office Defence in Georgia of the Republic 11 Mr. Yunus Emre Karaosmanoğlu Deputyof Turkey Minister of Defence of of the Republic of 12 Lt. Gen. Atanas Zapryanov (Ret.) Bulgaria 13 Mr. Lasha Darsalia Deputy Minister of Foreign Affairs of Georgia 14 Mr. Vytautas Umbrasas Vice-Minister of Defence of the Republic of Lithuania 15 Mr. Adam Reichardt SeniorEditor-in-Chief Research ofFellow, New EasternRoyal United Europe Services 16 Mr. Ewan Lawson Institute 17 Maj. Gen. (ret.) Harri Ohra-aho AmbassadorMinisterial Adviser, Extraordinary Ministry and of Plenipotentiary Defence of Finland of 18 H.E. Ihor Dolhov Ukraine to Georgia Ambassador-at-Large for Hybrid Threats, Ministry of 19 Amb. Eitvydas Bajarūnas ChargéForeign d’Affaires,Affairs of thea.i. Republicthe Embassy of Lithuania of the USA to 20 Ms. Elizabeth Rood Georgia Brigadier General Randall Simmons 21 JR. Director,Commanding Defense General Institution Georgia and Army Capacity National Building, Guard 22 Mr. Marc Di Paolo NATO 23 Vice Adm. -

Vakhtang Gomelauri Minister of Internal Affairs, Government of Georgia Cc: Josep Borrell Fontelles, High Representative/Vice-Pre

Vakhtang Gomelauri Minister of Internal Affairs, Government of Georgia Cc: Josep Borrell Fontelles, High Representative/Vice-President of the Commission for Foreign Affairs and Security Policy Helena Dalli, Commissioner for Equality Carl Hartzell, Head of the EU Delegation to Georgia Brussels, 28 June 2021 Subject: Call on Georgian authorities to protect Tbilisi Pride protesters and ensure their universal right to freedom of expression and peaceful assembly are effectively enjoyed Dear Vakhtang Gomelauri, Minister of Internal Affairs, Government of Georgia, Between 1-5 July, Tbilisi will see its Pride march celebrations take place. These will include 3 main activities throughout the five days, including the official premiere of “March for Dignity”, a documentary about the first-ever Tbilisi Pride Week in 2019 (1 July), the Pride Fest with local and international artists (3 July) and the Pride “March for Dignity”, co-organized by local social movements (5 July). Collectively, these will constitute a major event where the diversity of the LGBTI community is celebrated and affirmed. Pride demonstrations are peaceful tools for political advocacy and one way in which the universal right to freedom of expression and peaceful assembly is crystallised. They are a hallmark of the LGBTI activist movement, a pillar for social visibility and they are equally political demonstrations during which the community voices its concerns, highlights its achievements and gives the opportunity to its members to demonstrate in favour of equality. As such, the recent comments of the Chair of the Ruling Georgian Dream Party, Irakli Kobakhidze, who said that the Pride March had to be cancelled, are in contravention of these universal rights and of the established precedent in Tbilisi. -

Who Owned Georgia Eng.Pdf

By Paul Rimple This book is about the businessmen and the companies who own significant shares in broadcasting, telecommunications, advertisement, oil import and distribution, pharmaceutical, privatisation and mining sectors. Furthermore, It describes the relationship and connections between the businessmen and companies with the government. Included is the information about the connections of these businessmen and companies with the government. The book encompases the time period between 2003-2012. At the time of the writing of the book significant changes have taken place with regards to property rights in Georgia. As a result of 2012 Parliamentary elections the ruling party has lost the majority resulting in significant changes in the business ownership structure in Georgia. Those changes are included in the last chapter of this book. The project has been initiated by Transparency International Georgia. The author of the book is journalist Paul Rimple. He has been assisted by analyst Giorgi Chanturia from Transparency International Georgia. Online version of this book is available on this address: http://www.transparency.ge/ Published with the financial support of Open Society Georgia Foundation The views expressed in the report to not necessarily coincide with those of the Open Society Georgia Foundation, therefore the organisation is not responsible for the report’s content. WHO OWNED GEORGIA 2003-2012 By Paul Rimple 1 Contents INTRODUCTION .........................................................................................................3 -

Pre-Election Monitoring of October 8, 2016 Parliamentary Elections Second Interim Report July 17 - August 8

International Society for Fair Elections and Democracy Pre-Election Monitoring of October 8, 2016 Parliamentary Elections Second Interim Report July 17 - August 8 Publishing this report is made possible by the generous support of the American people, through the United States Agency for International Development (USAID) and the National Endowment for Democracy (NED). The views expressed in this report belong solely to ISFED and may not necessarily reflect the views of the USAID, the United States Government and the NED. 1. Introduction The International Society for Fair Elections and Democracy (ISFED) has been monitoring October 8, 2016 elections of the Parliament of Georgia and Ajara Supreme Council since July 1, with support from the United States Agency for International Development (USAID) and the National Endowment for Democracy (NED). The present report covers the period from July 18 to August 8, 2016. 2. Key Findings Compared to the previous reporting period, campaigning by political parties and candidates has become more intense. ISFED long-term observers (LTOs) monitored a total of 114 meetings of electoral subjects with voters throughout Georgia, from July 18 through August 7. As the election campaigning moved into a more active phase, the number of election violations grew considerably. Failure of relevant authorities to take adequate actions in response to these violations may pose a threat to free and fair electoral environment. During the reporting period ISFED found 4 instances of intimidation/harassment based on political affiliation, 2 cases of physical violence, 3 cases of possible vote buying, 4 cases of campaigning by unauthorized persons, 8 cases of misuse of administrative resources, 4 cases of interference with pre- election campaigning, 4 cases of use of hate speech, 7 cases of local self-governments making changes in budgets for social and infrastructure projects; 3 cases of misconduct by election commission members. -

Monitoring Court Proceedings of the Cases with Alleged Political Motives

MONITORING COURT PROCEEDINGS OF THE CASES WITH ALLEGED POLITICAL MOTIVES Summary Report 2020 MONITORING COURT PROCEEDINGS OF THE CASES WITH ALLEGED POLITICAL MOTIVES Summary Report THE REPORT WAS PREPARED BY HUMAN RIGHTS CENTER AUTHOR: GIORGI TKEBUCHAVA EDITED BY: ALEKO TSKITISHVILI GIORGI KAKUBAVA TRANSLATED BY: NIKOLOZ JASHI MONITORS: ANI PORCHKHIDZE TAMAR KURTAULI NINO CHIKHLADZE 2020 MONITORING COURT PROCEEDINGS OF THE CASES WITH ALLEGED POLITICAL MOTIVES Non-governmental organization the HUMAN RIGHTS CENTER, formerly the Human Rights Information and Documentation Center (HRC) was founded on December 10, 1996 in Tbilisi, Georgia. The HRIDC aims to increase respect for human rights, fundamental freedoms and facilitate the peace-building process in Georgia. To achieve this goal, it is essential to ensure that authorities respect the rule of law and principles of transparency and separation of powers, to eliminate discrimination at all levels, and increase awareness and respect for human rights among the people in Georgia. THE HUMAN RIGHTS CENTER IS A MEMBER OF THE FOLLOWING INTERNATIONAL NETWORKS: International Federation of Human Rights (FIDH); www.fidh.org World Organization against Torture (SOS-Torture – OMCT Network); www.omct.org Human Rights House Network; www.humanrightshouse.org Coalition for International Criminal Court; www.coalitionfortheicc.org ADDRESS: Akaki Gakhokidze Str. 11a, 3rd Floor, 0160 Tbilisi Tel: (+995 32) 237 69 50, (+995 32) 238 46 48 Fax: (+995 32) 238 46 48 Email: [email protected] Website: http://www.humanrights.ge; http://www.hridc.org The Report was prepared with the financial support of the National Endowment for Democracy (NED). The Report does not necessarily reflect the views of the donor. -

Opposition United National Movement Party Enters Georgian Parliament

“Impartial, Informative, Insightful” GEL 3.00 #104 (4908) TUESDAY, JUNE 1, 2021 WWW.MESSENGER.COM.GE Opposition United National Movement party enters Georgian Parliament BY VERONIKA MALINBOYM numerous occasions that the reason why political agreement, which is the basis for many priorities. This is important work the party refuses to sign the agreement consensus for ending the political crisis.” that needs the responsible participation of eorgia’s major opposition United proposed by the President of the Euro- Meanwhile, the US and EU ambassa- all of Georgia’s elected leaders. By signing G National Movement party will enter pean Council Charles Michel is because dors to Georgia expressed strong regret this agreement the UNM would demon- the parliament after a six-month boycott, of the amnesty that it extended upon the overy the UNM’s refusal to sign the EU- strate its commitment to carry out these chairman of the party, Nika Melia has party’s leader Nika Melia, stating that mediated agreement: fundamental objectives in the interest of announced. Melia added that despite its amnesty implies some sort of guilt, while "However, we strongly regret that the Georgia, its citizens, EU-Georgia relations decision, the United National Movement Nika Melia was just a political prisoner. United National Movement did not seize and Georgia’s Euro-Atlantic future," read party will still refrain from signing the The ruling Georgian Dream party the opportunity today to join the other par- the official statement reads. EU-brokered agreement between the also commented on the United National ties in signing the 19 April agreement. -

![Survey on Political Attitudes April 2019 1. [SHOW CARD 1] There Are](https://docslib.b-cdn.net/cover/0963/survey-on-political-attitudes-april-2019-1-show-card-1-there-are-800963.webp)

Survey on Political Attitudes April 2019 1. [SHOW CARD 1] There Are

Survey on Political Attitudes April 2019 1. [SHOW CARD 1] There are different opinions regarding the direction in which Georgia is going. Using this card, please, rate your answer. [Interviewer: Only one answer.] Georgia is definitely going in the wrong direction 1 Georgia is mainly going in the wrong direction 2 Georgia is not changing at all 3 Georgia is going mainly in the right direction 4 Georgia is definitely going in the right direction 5 (Don’t know) -1 (Refuse to answer) -2 2. [SHOW CARD 2] Using this card, please tell me, how would you rate the performance of the current government? Very badly 1 Badly 2 Well 3 Very well 4 (Don’t know) -1 (Refuse to answer) -2 Performance of Institutions and Leaders 3. [SHOW CARD 3] How would you rate the performance of…? [Read out] Well Badly answer) Average Very well Very (Refuse to (Refuse Very badly Very (Don’t know) (Don’t 1 Prime Minister Mamuka 1 2 3 4 5 -1 -2 Bakhtadze 2 President Salome 1 2 3 4 5 -1 -2 Zourabichvili 3 The Speaker of the Parliament 1 2 3 4 5 -1 -2 Irakli Kobakhidze 4 Mayor of Tbilisi Kakha 1 2 3 4 5 -1 -2 Kaladze (Tbilisi only) 5 Your Sakrebulo 1 2 3 4 5 -1 -2 6 The Parliament 1 2 3 4 5 -1 -2 7 The Courts 1 2 3 4 5 -1 -2 8 Georgian army 1 2 3 4 5 -1 -2 9 Georgian police 1 2 3 4 5 -1 -2 10 Office of the Ombudsman 1 2 3 4 5 -1 -2 11 Office of the Chief Prosecutor 1 2 3 4 5 -1 -2 12 Public Service Halls 1 2 3 4 5 -1 -2 13 Georgian Orthodox Church 1 2 3 4 5 -1 -2 4. -

Information As of 1 November 2014 Has Been Used in Preparation of This Directory. PREFACE

Information as of 1 November 2014 has been used in preparation of this directory. PREFACE The Central Intelligence Agency publishes and updates the online directory of Chiefs of State and Cabinet Members of Foreign Governments weekly. The directory is intended to be used primarily as a reference aid and includes as many governments of the world as is considered practical, some of them not officially recognized by the United States. Regimes with which the United States has no diplomatic exchanges are indicated by the initials NDE. Governments are listed in alphabetical order according to the most commonly used version of each country's name. The spelling of the personal names in this directory follows transliteration systems generally agreed upon by US Government agencies, except in the cases in which officials have stated a preference for alternate spellings of their names. NOTE: Although the head of the central bank is listed for each country, in most cases he or she is not a Cabinet member. Ambassadors to the United States and Permanent Representatives to the UN, New York, have also been included. Page 2 of 211 Key to Abbreviations Adm. Admiral Admin. Administrative, Administration Asst. Assistant Brig. Brigadier Capt. Captain Cdr. Commander Cdte. Comandante Chmn. Chairman, Chairwoman Col. Colonel Ctte. Committee Del. Delegate Dep. Deputy Dept. Department Dir. Director Div. Division Dr. Doctor Eng. Engineer Fd. Mar. Field Marshal Fed. Federal Gen. General Govt. Government Intl. International Lt. Lieutenant Maj. Major Mar. Marshal Mbr. Member Min. Minister, Ministry NDE No Diplomatic Exchange Org. Organization Pres. President Prof. Professor RAdm. Rear Admiral Ret.