The Spatial Pattern of Gentrification in Berlin

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Neighborhood Favorites

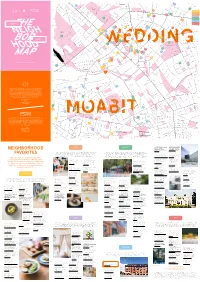

1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 Markstraße Müllerstraße Brienzer Str. 45 Usambarastraße 73 Togostraße Soldiner Str. Schwyzer Str. Swakopmunder Str. Damarastraße Liverpooler Str. ENGLISCHES Koloniestraße 60 Gotenburger Str. Prinzenallee VIERTEL Str. Drontheimer A Dubliner Str. Biesentaler Str. A 29 Osloer Str. OSLOER STRASSE ! RESTAURANTS Armenische Str. Windhuker Str. REHBERGE Barfusstraße Glasgower Str. Stockholmer Str. 80 56 Wriezener Str. ! CAFÉS 15 93 Osloer Str. Freienwalder Str. Grüntaler Str. SCHILLERPARK 96 Petersallee 86 ! SHOPS Iranische Str. Schwedenstraße Lüderitzstraße BORNHOLMER Togostraße 63 Indische Str. Bornholmer Str. STRASSE Afrikanische Str. Edinburger Str. Str. Bellermannstraße ! ACTIVITIES Koloniestraße Koloniestraße Heinz-Galinski-Straße 25 Müllerstraße Exerzierstraße ! CULTURE Ungarnstraße Türkenstraße Klever Str. Oudenarder Str. ! BARS WEDDING Groniger Str. Seestraße Otawlstraße Sonderburger Str. B Uferstraße Spanheimstraße B 20 Gottschedstraße 23 Kongostraße 87 94 Eulerstraße 85 Gropiusstraße 97 Malplaquetstraße NAUENER PLATZ 81 Stettiner Str. Sansibarstraße Liebenwalder Str. Buttmannstraße 12 16 Thurneystraße 22 77 Grüntaler Str. VOLKSPARK Transvaalstraße Pankstraße Togostraße Turiner Str. 91 REHBERGE Lüderitzstraße SEESTRASSE 53 Bornemannstraße Bastienstraße Hochstädter Str. Schulstraße Zingster Str. Schönstedtstraße Heidebrinker Str. 1 95 Böttgerstraße Behmstraße Guineastraße 32 68 Amsterdamer Str. 13 Maxstraße Müllerstraße 2 GESUNDBRUNNEN 59 Utrechter Str. 37 MOABIT Kameruner Str. Prinz-Eugen-Straße Sambesistraße 99 Schererstraße Wiesenstraße Genter Str. 61 58 Antwerpener Str. Kösliner Str. Adolfstraße 6 Senegalstraße Dualastraße 76 41 Reinickendorfer Str. 54 Ramierstraße Lütticher Str. 51 Ugandastraße Nazarethkirchstraße C C Hochstraße C HUMBOLDTHAIN LEOPOLDPLATZ Tangastraße Seestraße 82 Brüsseler Str. Ruheplatzstraße Wiesenstraße Amrumer Str. 14 65 Graunstraße Pankstraße Antonstraße 90 Swinemünder Str. Dohnagestell Ostender Str. 83 30 Pasewalker Str. Pasewalker Str. HUMBOLDTHAIN Putbusser Str. Genter Str. 8 55 89 98 Rügener Str. -

Shifting Neighbourhood Dynamics and Everyday Experiences of Displacement in Kreuzberg, Berlin

Faculty of Humanities School of Design and the Built Environment Shifting Neighbourhood Dynamics and Everyday Experiences of Displacement in Kreuzberg, Berlin Adam Crowe 0000-0001-6757-3813 THIS THESIS IS PRESENTED FOR THE DEGREE OF Doctor of Philosophy of Curtin University November 2020 Declaration I hereby declare that: I. the thesis is being submitted in partial fulfilment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy II. the research is a result of my own independent investigation under the guidance of my supervisory team III. the research presented and reported in this thesis was conducted in accordance with the National Health and Medical Research Council’s (NHMRC) National Statement on Ethical Conduct in Human Research (2007). The proposed study received human research ethics approval from the Curtin University Human Research Ethics Committee (EC00262), Approval Number HRE2017-0522 IV. the thesis contains no material previously published by any other person except where due acknowledgement has been made V. this thesis contains no material which has been accepted for the award of any other degree or diploma in any university Signature: Adam Joseph Crowe Date: November 12, 2020 ii Abstract This research explores the socio-spatial impacts of shifting housing and neighbourhood dynamics in the gentrifying neighbourhoods of Kreuzberg, Berlin. The locality represents a prime example of an inner-city locality that has been reimagined and transformed by a series of powerful actors including, but not limited to, an increasingly financialised real-estate sector, a tourism industry promoting Kreuzberg as a destination for higher-income groups, and a city-state government embracing and promoting entrepreneurial approaches to urban governance. -

Bezirksamt-Mitte.Pdf

] BEZIRKSAWIT IMiTTE be i / VON BERLIN Regionaldienstleitung Regionaler Sozialpädagogischer Dienst It Kerstin Kubisch-Piesk | Jug R 3 Tel. 030/9018-45340 | R. 307 Der Regionale Sozialpädagogische Dienst (RSD) steht Kin- [email protected] dem. Jugendlichen, Eltern und Familien bei Problemen oder Konflikten mit Beratung, Vermittlung und Informa- Geschäftszimmer tionen zur Seite und entwickelt mit ihnen gemeinsam Lö- Daniela Beig | Jug R 301 sungen. Zur Unterstützung bietet der RSD auch individu- Tel. 030/9018-45310 | R. 302 eile Erziehungshilfen an. Bezirksamt Mitte [email protected] Wenn Sie das erste Mal mit uns in Kontakt treten, dann von Berlin erreichen Sie uns über den Tagesdienst vor Ort: Jugendanit Regionale Jugend- und Familienförderung Wann? Di 9-12 Uhr, Do 16-18 Uhr Regionaldienst Wo? Region Gesundbrunnen Selbstbewusstsein, Selbständigkeit und soziales Mitein- Grüntaler Straße 21, 2. OG /4. OG Gesundbrunnen ander fördern und zum Mitgestalten in der Gesellschaft 13357 Berlin anregen, das sind Kernziele der Jugendarbeit. InJugend- Unterstützung, die ankommt. einrichtungen können Jugendliche ihre Talente entfal- oder telefonisch zu folgenden Zeiten: ten, Neues ausprobieren und persönliche Probleme mit professionellen Ansprechpartner*innen besprechen. Wann? Mo, Di., Mi 9-15 Uhr, Do 12-18 Uhr, Fr 9-14 Uhr Familien werden durch Angebote der Familienförderung Wie? Tel. 030/9018-45355 bei der Bewältigung von Erziehungs- und Bildungsauf- Fax030/9018-45331 gaben unterstützt. Dadurch wird die aktive Beteiligung von Familien, Kindern und Jugendlichen am gesellschaft- Für alle weiteren Anliegen sind wir nach vorheriger lichen Leben gefördert. Terminvereinbarung gerne für Sie da. Sozialraumkoordinator Osloer Straße Weitere Informationen erhalten Sie auch unter: Peter Barton | Jug R 3401 www.berlin.de/ba-mitte Tel. -

Mitte Friedrichstr. 96, 10117 Berlin, Germany Tel.: (+49) 30 20 62 660

HOW TO GET THERE? WHERE TO FIND NH COLLECTION BERLIN MITTE FRIEDRICHSTRASSE? Area: Mitte Friedrichstr. 96, 10117 Berlin, Germany Tel.: (+49) 30 20 62 660 FROM THE AIRPORT - From Tegel Airport: Take the bus TXL, which runs every 20 minutes, to get to the "Unter den Linden/Friedrichstraße". From there, walk to the S-Bahn station “Friedrichstraße” - the hotel is on the right site. It is a 35 minute trip. Taxi: The 20-25 minute cab ride costs about €25. - From Schönefeld Airport: Take the train S9 to Spandau. It runs every 20 minutes. Exit at "Friedrichstraße" station. You will find the hotel on the right side, next to the station. It is a 40 minute trip. Taxi: The 30-40 minute cab ride costs about €55. FROM THE TRAIN STATION From Berlin Central Station (Hauptbahnhof): Take one of the regional trains (S3, S5, S7, S9 or RB14). Exit at “Friedrichstrasse” station. You will find the hotel on the right side, next to the station. It is a 5 minute trip. Taxi: The 10 minute cab ride costs about €10. Please note: For public transportation in zones A, B, and C, choose between a single ticket (3,40€), a day ticket (7,70€) or a ticket for one week (37,50€). You can take the train and the bus in all sectors (ABC). For public transportation in zones A and B exclusively: choose between a single ticket (2,80€), a day ticket (7,00€) or a ticket for a week (30,00€). You can take the train and the bus in sector A and B. -

Stadtteilarbeit Im Bezirk Mitte

Stadtteilarbeit im Bezirk Mitte In unseren Nachbarschaftstreffpunkten finden Sie viele ver- Stadtteilzentrum schiedene Angebote für Jung und Alt. Hier treffen sich Nach- barinnen und Nachbarn in Kursen oder Gruppen, zu kultu- Selbsthilfe Kontaktstelle rellen Veranstaltungen, um ihre Ideen für die Nachbarschaft Nachbarschaftstreff umzusetzen, um sich beraten zu lassen oder um Räume für Familienzentrum eigene Projekte und Festivitäten anzumieten. Mehrgenerationenhaus Osloer mit Rollstuhl zugänglich Alexanderplatz Straße WC rollstuhlgerechtes WC 19 1 Begegnungsstätte Die unterschiedlichen Spandauer Straße 21 Begrifflichkeiten der Bezirksamt Mitte von Berlin 18 Nachbarschaftseinrichtungen Spandauer Str. 2 | 10178 Berlin Parkviertel liegen an den jeweiligen Tel. 242 55 66 Förderprogrammen. 22 25 17 www.berlin.de/ba-mitte WC 20 2 Kieztreff Koepjohann Wedding Koepjohann’sche Stiftung Zentrum Große Hamburger Str. 29 10115 Berlin | Tel. 30 34 53 04 4 www.koepjohann.de WC Brunnenstraße Nord 3 KREATIVHAUS Stadtteilkoordination 26 5 8 KREATIVHAUS e.V. | Fischerinsel 3 | 10179 Berlin 7 6 Tel. 238 09 13 | www.kreativhaus-tpz.de WC Brunnenstraße Nord Moabit West 10 4 Begegnungsstätte im Kiez Brunnenstraße Jahresringe Gesellschaft für Arbeit | 15 Süd und Bildung e.V. Stralsunder Str. 6 16 13355 Berlin | Tel. 464 50 36 13 www.jahresringe-ev.de/ Moabit Ost 9 begegnungsstatten.html WC 14 2 5 Begegnungsstätte Haus Bottrop 12 Alexanderplatz Selbst-Hilfe im Vor-Ruhestand e.V. Schönwalder Str. 4 | 13347 Berlin Tel. 493 36 77 | www.sh-vor-ruhestand.de WC 1 6 Familienzentrum Wattstraße Pfefferwerk Stadtkultur gGmbH | Wattstr. 16 11 | | 13355 Berlin Tel. 32 51 36 55 www.pfefferwerk.de Regierungs- WC viertel 3 7 Kiezzentrum Humboldthain Tiergarten Süd DRK-Kreisverband Wedding / Prenzlauer Berg e. -

The New Berlin: Exploring Its Political, Social, and (Multi)Cultural Life

The New Berlin: Exploring its political, social, and (multi)cultural life Arts and Sciences 137, Freshman Seminar Winter 2011, 1 Credit (Letter Grade) Thursdays, 3:304:18 (or Mondays, 2:303:18) Instructor: Carmen Taleghani‐Nikazm Office: 425 Hagerty Hall Email: taleghani‐[email protected] Office Hours: Wednesdays, 10:00‐12:00 or by appointment Course Description In this seminar we will explore Berlin, the capital city of Germany, as it is today. Class discussions will focus on recent changes in Berlin's political, social and cultural life with its diversity, richness and complexities. We will pay special attention to Berlin's multi‐ethnic society and learn about the old and new migrant communities in Berlin. We will read a collection of texts that have used different research approaches to examine the city's social diversity and the problems and possibilities that arise in such a cosmopolitan environment. The Seminar Objectives • To gain knowledge of a very distinctive, exciting city and its richness in history, society, culture and politics • To understand and appreciate the range of diversity found in the German population • To acquire some insights into what it means to live in a society that is becoming more and more diverse Texts There is no textbook for this class. All class materials including links to various websites are available on the seminar's course site/Carmen. Course Evaluation Attendance and participation in class discussions 40% Completion of discussion and reaction questions 30% Short research paper (700‐800 words) 30% Course Expectations You are expected to attend every class session prepared to discuss the ideas presented in readings and lectures. -

Altes Krankenhaus Staaken: the Metropolitan Park Information in Leichter Sprache

Altes Krankenhaus Staaken: The Metropolitan Park Information in Leichter Sprache Das Gelände des ehemaligen Krankenhaus Staaken liegt ganz im Westen des Bezirks Spandau. Es hat sich in den letzten 100 Jahren mehrmals stark verändert. Das Gelände und die Gebäude wurden über 20 Jahre nicht genutzt und sind stark verfallen und beschädigt. Jetzt sollen die Gebäude als Wohnungen umgebaut werden zum sogenannten »Metropolitan Park«. Was war auf dem Gelände früher? Im Jahr 1915 kaufte die Firma Luftschiffbau Zeppelin AG das Gelände. Das war vor über 100 Jahren. Die Firma baute hier Zeppeline und der Fabrik-Standort Staaken wurde für kurze Zeit weltberühmt. Mitte der 1920er Jahre gehörte das Gelände dann der Deutschen Lufthansa AG. Hier war damals der modernste Standort in Deutschland zur Wartung und Reparatur von Flugzeugen. Ab Mitte der 1930er Jahre wurde das Gelände militärisch genutzt und zu einem Standort der Luftwaffe der Wehrmacht umgebaut. Dazu gehörte auch der Neubau von Kasernen für Soldaten und andere Beschäftigte. Im 2. Welt-Krieg wurde das Gelände von Bomben zerstört, aber die Gebäude bekamen nur geringe Beschädigungen. 1 Nach dem 2. Welt-Krieg nutzte die Finanz-Hochschule der DDR das Gelände. Ab dem Jahr 1958 war dort dann eine Außenstelle vom Kreis-Krankenhaus Nauen. Dafür musste damals viel umgebaut werden. Das Krankenhaus nutzte das Gelände, bis es im Jahr 1998 schließen musste. Was ist jetzt auf dem Gelände geplant? Die Prinz von Preussen Grundbesitz AG hat das Gelände im Jahr 2016 gekauft, um dort Wohnungen zu bauen. Insgesamt soll es über 400 Wohnungen geben. Ungefähr die Hälfte davon wird in umgebauten Gebäuden vom ehemaligen Krankenhaus Staaken sein. -

Informationen Des Bezirksamtes Mitte Von Berlin Für Geflüchtete Menschen – Stand 04 / 2016

InformationenInformationen des des BezirksamtesBezirksamtes MitteMitte vonvon BerlinBerlin für geflüchtetefür geflüchtete Menschen Menschen Informationen des Bezirksamtes Mitte von Berlin für geflüchtete Menschen – Stand 04 / 2016 - Inhaltsverzeichnis Ansprechperson Gesamtkoordination Flüchtlingsfragen S. 1 Gesundheit Ansprechperson Koordination S. 2 Beratungsstelle für behinderte und krebskranke Menschen S. 3 Beratungsstelle für kindliche Entwicklungsförderung S. 4 Beratungsstelle für sehbehinderte Menschen S. 5 Hygiene und Umweltmedizin S. 6 Kinder- und Jugendgesundheitsdienst (KJGD) S. 7 Kinder- und Jugendpsychiatrischer Dienst (KJPD) S. 9 Sozialpsychiatrischer Dienst S. 10 Zahnärztlicher Dienst S. 12 Zentrum für Familienplanung und Schwangerschaft S. 13 Zentrum für sexuelle Gesundheit S. 15 Externe Anlaufstellen medizinische Versorgung S. 16 Kinder und Jugend Erziehungs- und Familienberatung S. 18 Kindertagesbetreuung S. 20 Regionaler Sozialpädagogischer Dienst, Kindernotdienst, Ansprechpersonen S. 22 Schule Einschulung in die Grundschule S. 25 Einschulung in die Oberschule S. 27 Deutschkurse S. 29 Bürgerdienste Ansprechperson Koordination S. 31 Ansprechperson Back Office S. 32 Bürgerämter S. 33 Standesamt S. 35 Wohnraumvermittlung S. 36 Bibliotheken Stadtbiliothek Mitte S. 38 Anlagen Beratungsstellen (Aufenthaltsrecht, Asylrecht, Sozialleistungen) Bibliotheken berlinweit Integrationslotsen Integrationsbüro Mitte Koordination flüchtlingsrelevanter Fragen im Bezirksamt Mitte Ansprechperson: Frau Majer (030) 9018 - 33749 (030) 9018 -

Renaming Streets, Inverting Perspectives: Acts of Postcolonial Memory Citizenship in Berlin

Focus on German Studies 20 41 Renaming Streets, Inverting Perspectives: Acts Of Postcolonial Memory Citizenship In Berlin Jenny Engler Humbolt University of Berlin n October 2004, the local assemblyman Christoph Ziermann proposed a motion to rename “Mohrenstraße” (Blackamoor Street) in the city center of Berlin (BVV- Mitte, “Drucksache 1507/II”) and thereby set in train a debate about how to deal Iwith the colonial past of Germany and the material and semantic marks of this past, present in public space. The proposal was discussed heatedly in the media, within the local assembly, in public meetings, in university departments, by historians and linguists, by postcolonial and anti-racist activists, by developmental non-profit organizations, by local politicians, and also by a newly founded citizens’ initiative, garnering much atten- tion. After much attention was given to “Mohrenstraße,” the issue of renaming, finally came to include the so-called African quarter in the north of Berlin, where several streets named after former colonial regions and, most notably, after colonial actors are located. The proposal to rename “Mohrenstraße” was refused by the local assembly. Nev- ertheless, the assembly passed a resolution that encourages the “critical examination of German colonialism in public streets” (BVV-Mitte, “Drucksache 1711/II”) and, ultimately, decided to set up an information board in the so-called African quarter in order to contextualize the street names (BVV-Mitte, “Drucksache 2112/III”). How- ever, the discussion of what the “critical -

Mitte Friedrichshain-Kreuzberg Pankow

► Vorwort 5 Mitte 1 Das »himmelbeet« in Wedding 6 2 Einkäufen im Mini-Kaufhaus in Wedding 8 3 Smart Eating in der Data Kitchen 10 4 Bibliothek am Luisenbad 12 5 Gleim-Oase: die grüne Insel im Wedding 14 6 Leckere Burger in ausgefallener Location 16 7 Franzose mit witzigem Menü-Konzept 18 8 Cocktail trinken in einer versteckten Bar 20 9 Katz Orange: Restaurant in alter Brauerei 22 10 Staunen in der Wunderkammer Olbricht 24 11 Die Dachterrasse des Hotel AMANO 26 12 Brötchen holen in Sarah Wieners Bio-Bäckerei 26 13 Cowshed Spa im Soho House 28 14 Tadshikische Teestube: märchenhaft Tee genießen 30 15 Kennedy Museum: in der Jüdischen Mädchenschule 32 16 Beeindruckende Boros Collection 34 17 Entspannen über den Dächern der Stadt 36 18 Alter Grenzturm am Potsdamer Platz 36 19 Ein Tag Luxus, bitte! 38 Friedrichshain-Kreuzberg 20 Sonnenuntergang auf der Modersohnbrücke 40 21 Das beliebteste Outlet der Stadt 42 22 Minigolf bei Schwarzlicht 44 23 Street Food Thursday 46 24 Panoramablick über Kreuzberg 46 25 Akupunktur, die sich jeder leisten kann 47 26 Ein Besuch im Pfefferhaus 48 27 Die kleinste Disko der Welt 50 28 Crazy Hot Dogs 50 29 Kalifornien zum Schlecken 52 Pankow 30 Erinnerungen in der Alten Bäckerei Pankow 54 31 Die Ruine des Kinderkrankenhauses in Weißensee 56 32 Lustige Tischtennis-Bar im Prenzlauer Berg 56 33 Türkische Küche - modern interpretiert 58 34 Stulle essen bei Suicide Sue 60 35 Onkel Philipp's Spielzeugwerkstatt 62 36 Verwunschene Oase auf dem Friedhof 64 37 Zur Ruhe kommen im Stadtkloster Segen 66 38 Entspannen im Ruhepool -

Berlin Zentral Charlottenburg-Wilmersdorf

Berlin zentral Marzahn Pankow SEKIS Selbsthilfe-Kontakt- und Beratungsstelle KIS Kontakt- und Informationsstelle Selbsthilfe Kontakt- und Informationsstelle Marzahn-Hellersdorf für Selbsthilfe im Stadtteilzentrum Pankow Bismarckstr. 101 | 10625 Berlin Alt-Marzahn 59 A | 12685 Berlin Schönholzer Str. 10 | 13187 Berlin Tel 892 66 02 Tel 54 25 103 Tel 499 870 910 Fax 890 285 40 Fax 540 68 85 Mail [email protected] Mail [email protected] Mail [email protected] www.kisberlin.de www.sekis.de www.wuhletal.de Mo + Mi 15-18, Do 10-13 Uhr Mo 12-16, Mi 10-14 und Do 14-18 Uhr Mo 13-17, Di 15-19, Fr 9-13 Uhr und nach Vereinbarung Charlottenburg-Wilmersdorf Pankow-Buch SelbsthilfeKontaktstelle Mitte Selbsthilfe- und Stadtteilzentrum Charlottenburg-Wilmersdorf SEKIS im Bucher Bürgerhaus Bismarckstr. 101 | 10625 Berlin Selbsthilfe Kontakt- und Beratungsstelle Mitte Franz-Schmidt-Str. 8-10 | 13125 Berlin Tel 892 66 02 - StadtRand gGmbH Tel 941 54 26 Mail [email protected] Perleberger Str. 44 | 10559 Berlin Fax 941 54 29 www.sekis.de Tel 394 63 64 Mail [email protected] Mo 12-16, Mi 10-14, Do 14-18 Uhr Tax 394 64 85 www.albatrosggmbh.de Mail [email protected] Di 15-18, Do + Fr 10-13 Uhr www.stadtrand-berlin.de Friedrichshain-Kreuzberg Mo, Di 10-14, Do 15-18 Uhr Selbsthilfe-Treffpunkt Friedrichshain-Kreuzberg Mi 10-13 Uhr (in türkischer Sprache) Reinickendorf Boxhagenerstr. 89 | 10245 Berlin und nach Vereinbarung Tel 291 83 48 Selbsthilfe- und Stadtteilzentrum Reinickendorf, Fax 290 49 662 Neukölln Süd Günter-Zemla-Haus Mail [email protected] Eichhorster Weg 32 | 13435 Berlin www.selbsthilfe-treffpunkt.de Selbsthilfe- und Stadtteilzentrum Neukölln-Süd Tel 416 48 42 Di + Fr 10-13; Mi + Do 15-18 Uhr Lipschitzallee 80 | 12353 Berlin Fax 41 74 57 53 Tel 605 66 00 Mail [email protected] Hohenschönhausen Fax 605 68 99 www.unionhilfswerk.de/selbsthilfe Mail [email protected] Di + Do 14-18, Mi + Fr 10-14 Uhr Selbsthilfe Kontakt- und Beratungsstelle - Horizont www.selbsthilfe-neukoelln.de Ahrenshooper Str. -

District Heating for Berlin

GENERATION SPECIALIST TOPIC 43 The new cogeneration plant from Vattenfall Wärme in Berlin-Marzahn proves that industrial facades do not have to be dreary: With the day’s changing light, the CHP plant also changes its appearance Source: Siemens Energy District Heating for Berlin Vattenfall Wärme Berlin has not only achieved its goal of halving CO2 emissions by 2020, but even exceeded them. A milestone in the concept of reducing emissions: one of Europe’s most modern combined heat and power plant in Berlin-Marzahn that as general contractor, Siemens Energy built – in just over three years. The history of the Marzahn cogen- 2020 Siemens Energy handed over heating in eastern Berlin area. eration plant is closely intertwined the new cogeneration plant on a Combined, the two plants serve with that of the city of Berlin. The turnkey basis after only a little over around 450,000 households – only city intends to be CO2-free by 2050. three years construction time. Soon in the eastern part of the city, by the No easy undertaking. This is why thereafter it went into commercial way, as underground the city is still the power company Vattenfall operation. divided. The eastern part has a two- Wärme Berlin committed itself in a The plant has an electrical output pipe system, while West Berlin has climate protection agreement to the of around 273 MW and a thermal a three-pipe system for district city Berlin to halve its CO2 emis- output of around 232 MW. The heart heating. sions – compared to 1990 – in the of the plant is an SGT5-2000E gas German capital by 2020.