Objectives and Integrated Approaches for the Control of Brown Tree Snakes: an Updated Overview

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

SWIFTS Family MICROPODIDB Vol

SWIFTS Family MICROPODIDB Vol. I., p. 122. THROUGHOUTthe hills of the Malay Peninsula this family is very common, and probably all the species that are known from the area will at one time or another be found within the limits of the present volume, exeept the Malay house-swift and one or two of the edible-nest swiftlets, which are very difficult to distinguish, and some of which appear to be purely coastal. Tail much stiffened, with naked, I needle-like bristly points . Tail not so stiffened . Wing exceeding 6'5 in. ; rump dark . Wing less than j'j in. ; rump grey . Smaller, wing less than 7'5 in. ; chin and throat pale smoky brown . Larger, wing nearly S in. ; chin and throat darker brown 4 Feathers before the eye, white Hiru~zdaplisgigalzfea indica, p. 62 4 - C Feathers before the eye, black Hirz~ndal-,1.t~ gigantea gigafltea, IL p. 62 J Toes all directed forwards . hfict~opz~spncijczts cooki, p. 64 j ( Toes not all directed forwards G ,- Tail much forked . Tnclioi,~zis batnssiensis irtfimzatus, 6' P. 65 [ Tail not or only slightly forked f Much smaller, wing less than 4.j in. ; ( feathers below broadly margined with white Collocalia li+%chicya+zoptila, p. 66 Much larger, M ing more than 5.1 in. ; I feathers below, uniform . More glossy black ; wing exceeding i 6 in. Collocnlia gigas, p. 6 j Browner, less glossy ; wing not more than j'j in. Collocalia i~tnonzinata,p. 65 61 THE BIRDS OF THE MALAY PENINSULA Nirundapus gigantea giganten The Large Spinetail Swift V0l. -

BIRDS of HALIMUN-SALAK NATIONAL PARK, WEST JAVA, INDONESIA: Saitou, N

Treubia 43: 31–46, December 2016 Treubia 43: 47–70, December 2016 BIRDS OF HALIMUN-SALAK NATIONAL PARK, WEST JAVA, INDONESIA: Saitou, N. & M. Nei 1987. The neighbor-joining method: a new method for reconstructing phylogenetic trees. Molecular Biology and Evolution, 4: 406-425. ENDEMISM, CONSERVATION AND THREATENED STATUS Simmons, N.B. 2005. Order Chiroptera. In: Wilson, D.E. & D.M. Reeder (eds.). Mammal Species of the Dewi M. Prawiradilaga World: A Taxonomic and Geographic Reference. Baltimore: John Hopkins University Press. pp. 312- Museum Zoologicum Bogoriense, Research Center for Biology, Indonesian Institute of Sciences (LIPI) 529. Jl. Raya Jakarta-Bogor Km 46 Cibinong 16911, Indonesia e-mail: [email protected] Suyanto, A. 2001. Kelelawar di Indonesia. Bogor: Lembaga Ilmu Pengetahuan Indonesia. 126 pp. Temminck, C.J. 1827 (1824)-1841. Monographies de Mammalogie, ou description de quelques genres de Received: 8 August 2016; Accepted: 5 December 2016 mammiferes, dont les espèces ont été observées dans les différens musées de l’Europe. C.C. Vander Hoek, Leiden, 392 pp. ABSTRACT Thompson, J.D., T.J. Gibson & F. Plewniak 1997. The Clustal X Windows Interface: Flexible Strategies for Multiple Sequence Alignment Aided by the Quality Analysis Tools. Nucleic Acids Research, 24: Bird surveys and long-term bird monitoring in Gunung Halimun-Salak National Park were 4876-4882. conducted between 1998 and 2009 to obtain comprehensive data on the bird species in the area. Compilation of bird data from this study and other studies have recorded a total of 271 species, which is about 53.4% of van Strien, N.J. 1986. Abbreviated checklist of the mammals of the Australian Archipelago. -

2003-2004 Recovery Report to Congress

U.S. Fish & Wildlife Service Report to Congress on the Recovery of Threatened and Endangered Species Fiscal Years 2003-2004 U.S. Fish & Wildlife Service Endangered Species Program www.fws.gov/endangered December 2006 The U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service is responsible under the Endangered Species Act for conserving and recovering our nation’s rarest plant and animal species and their habitats, working in cooperation with other public and private partners. From the Director Endangered Species Program Contacts Do you want more information on a particular threatened or endangered species or recovery effort near you? Please contact the Regional Office that covers the This 2004 report provides an update on the State(s) you are interested in. If they cannot help you, they will gladly direct you recovery of threatened and endangered species to the nearest Service office. for the period between October 1, 2002, and Region Six — Mountain-Prairie September 30, 2004, and chronicles the progress Washington D.C. Office Region Four — Southeast 134 Union Boulevard, Suite 650 of efforts by the Fish and Wildlife Service and Endangered Species Program 1875 Century Boulevard, Suite 200 Lakewood, CO 80228 the many partners involved in recovery efforts. 4401 N. Fairfax Drive, Room 420 Atlanta, GA 30345 http://mountain-prairie.fws.gov/endspp Arlington, VA 22203 http://www.fws.gov/southeast/es/ During this time, recovery efforts enabled three http://www.fws.gov/endangered Chief, Division of Ecological Services: species to be removed from the Endangered and Chief, -

FIELD GUIDES BIRDING TOURS Borneo

Field Guides Tour Report Borneo Jun 7, 2012 to Jun 24, 2012 Rose Ann Rowlett & Hamit Suban Sunrise over craggy Mt. Kinabalu, as seen from our doorsteps at the Hill Lodge inside Kinabalu Park. (Photo by tour participant Fred Dalbey) It was another fabulous tour to Borneo! As always, it was different from all previous tours in many of the specifics, from the weather (windy and rainy in the highlands this trip; surprisingly dry in the lowlands) to some of the birds and other critters observed. But there is great overlap among many of the spectacular basics from one tour to the next. And we had another wonderful sampling of the best of Borneo. In our efforts to overcome jetlag, we all arrived early and managed to get in a little extra birding pre-tour. Most folks went to Manukan Island for a morning, and we all went to the KK Wetland the day before the tour started, seeing a handful of species we wouldn't see on our official tour route. I've included those species in the list below since most folks in the group were experiencing Asian birding for the first time. Our most exciting encounter was with a pair of White-breasted Waterhens duetting as we watched at close range. We began officially in the Crocker Range, where we saw a number of highland endemics, from the usually very tough Whitehead's Spiderhunter to Mountain and Bornean barbets, Bornean Bulbul, Bornean Leafbird, and endearing flocks of Chestnut-crested Yuhinas, not to mention the non-endemic but dramatic Long-tailed Broadbill. -

Sabah, Borneo August 20Th – September 5Th 2017 Marcel Gil Velasco & Laura Abad

Sabah, Borneo August 20th – September 5th 2017 Marcel Gil Velasco & Laura Abad Sabah, August - September 2017 1 Please email me if you want to get it. All the sounds are Introduction available in xeno-canto.org. This was my first trip to a tropical country and so I Yann Muzika and Daniel López Velasco had been in didn’t know what to expect. Despite I had read all the the area a couple of months before and provided ex- trip reports available, gathered as much information tremely useful information and advice about the iti- as possible from friends who had just been there and nerary, accommodation options and local contacts. I studied both the field guides and some sound libra- want to thank them here once again. ries, I was still scared of not being able to find my most desired species. Apart from some easy species, Borneo is probably not the best option for your first tropical experience. The number of species is not as high as in Itinerary the Neotropics and some areas aren’t easy to explo- re, with a very limited accommodation offer and not Since we had a stretched budget and schedule (and Lau- many facilities such as canopy walks or observation ra wanted to spend some days diving in the amazing towers. It’s still far from the actual challenges found reefs of the eastern islands), we removed everything in remote places such as Papua New Guinea, but I still that wasn’t “needed” to see the target species. This is, wouldn’t describe it as easy. -

Westernjava2013.Pdf

Birding Western Java (M. Grundsten, Sweden) 2013 Western Java, July 19th - 27th 2013 Front cover Pied Shrike-babbler Pteruthius flaviscapis female/1cy, Gunung Gede National Park July 23rd. Relatively small- sized endemic to mountains of western Java, compared to other mainland South-east Asia-forms of the White- browed Shrike-babbler-complex. Participants Måns Grundsten, [email protected], compiler and most photos, Oscar Carheden, Anders Haglund, Jonas Nordin and Mathias Näslund, Sweden Highlights • The critically endangered Black-winged Starling seen both at classic Muara Angke and also at Pulau Dua where very rarely observed. • One elusive Javan White-eye when we had almost given up at Pulau Dua. • Javan Banded Pittas calling everywhere at Carita. • The cuckoo-bonanza at Carita, where we heard Square-tailed Drongo, Plaintive, Rusty-breasted and Bay-banded from the exact same spot at late evening. • Night-walking in Carita with Javan Frogmouth, Sunda Scops-Owl and Javan Slow Loris. • Beautiful Black-naped (Carita) and Pink-headed Fruit Doves (Gede). • Mouth-watering Javan Cochoas and Javan Trogons below the steaming hot springs of Air Panas. • Excellent views of the ground-dwellers: Pygmy Wren-babbler, Javan Tesia, Eyebrowed Wren- Babbler and Lesser Shortwing. • The smell of Silvery Javan Gibbons! • A rough climb to the summit of Gunung Gede in bad weather but still scoring Volcano Swiftlet. • A chattering group of rare Rufous-fronted Laughingthrushes above the junction. The worlds most southerly species of laughingthrush. • A perched Javan Kingfisher close to the entrance gate at Gunung Halimun. • The cool Stachyris-babblers: White-bibbed, Crescent-chested and White-breasted. -

Presentation

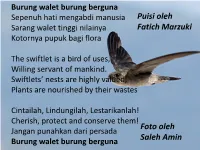

Burung walet burung berguna Sepenuh hati mengabdi manusia Puisi oleh Sarang walet tinggi nilainya Fatich Marzuki Kotornya pupuk bagi flora The swiftlet is a bird of uses, Willing servant of mankind. Swiftlets’ nests are highly valued; Plants are nourished by their wastes Cintailah, Lindungilah, Lestarikanlah! Cherish, protect and conserve them! Foto oleh Jangan punahkan dari persada Burung walet burung berguna Saleh Amin “The birds that never rest” A personal record of 60 years of collaborative research into the biology of swiftlets (Aves, Apodidae, Collocaliini) Gathorne Cranbrook Apodiformes, Apodidae, Collocaliini, Swiftlets. Salanganes, Salanganen Burung layang-layang walet/walit Swift or swallow yan 燕 swiftlets jin si yan 金絲燕 edible nests yan wo 燕窝 •A group of birds with unIque adaptive characters, maximum diversity in S-E Asia. •Long cultural and economic associations •An edible animal product, potentially utilised without harm to the producer. • A ‘functional’ food, protective & restorative •Changing intensity of human/bird interaction, with surprising outcomes in mid/late 20th century • An opportunity to use new laboratory tools to examine complex relationships 1956 - 1957 Sarawak 1968 Gombak GATHORNE, Earl of CRANBROOK 2014 2018 World range of Swiftlets Hainan Is Seychelles Is Fiji Vanuatu Greatest diversity [at least 8 species] Two influential books Influential contributors to regional swiftlet research (1) Erwin Stresemann Frederick Nutter Chasen Ernst Mayr Carl Gibson-Hill Soekarja Somadikarta Personal life-changing influence: Major Tom Harrisson: special forces 1945, Government Ethnologist 1946 & Curator, Sarawak Museum 1947 - 1967 Influential people (3) Jonny: - Vanuatu 1971 “The birds that never rest” Historic, cultural & socio-economic importance SWIFTLETS Birds’-nest soup birds Builders of edible nests Unique characters 1. -

The Species of White-Nest Swiftlets (Apodidae, Collocaliini) of Malaysia and the Origins of House-Farm Birds: Morphometric and Genetic Evidence

FORKTAIL 29 (2013): 107–119 The species of white-nest swiftlets (Apodidae, Collocaliini) of Malaysia and the origins of house-farm birds: morphometric and genetic evidence EARL OF CRANBROOK, GOH WEI LIM, LIM CHAN KOON & MUSTAFA ABDUL RAHMAN The taxonomy of South-East Asian swiftlets (Apodidae, Collocaliini) has proved challenging because of their limited variation in size and plumage colouration. Of particular interest are ‘white-nest’ swiftlets, whose nests, built almost entirely of hardened secretions from paired sublingual salivary glands, are valued in the edible birds’-nest trade. The natural breeding sites of white-nest swiftlets are caves or grottoes but, for over a century, there has been a progressive increase in numbers occupying man-made structures. Through most of South-East Asia there is now a developed industry, utilising sophisticated practices to attract and retain white-nest swiftlets in purpose-made buildings, known as ‘house-farms’—a novel form of domestication. A review of the systematics of wild populations based on museum skins collected in late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries, before the expansion of house-farms, concludes that there are two largely allopatric species of white-nest swiftlet in Malaysia, identified as Grey-rumped Swiftlet Aerodramus inexpectatus, with subspecies A. i. germani and A. i. perplexus, and Thunberg’s or Brown-rumped Swiftlet Aerodramus fuciphagus, with subspecies A. f. fuciphagus and A. f. vestitus. During 2003 to 2010, house-farm swiftlets in southern Thailand, east and west coasts of Peninsular Malaysia, Sarawak, Java and southern East Kalimantan, Indonesia, were photographed to show variability in plumage of the rump. -

Borneo (Sabah) - a Birdwatching Tour

Borneo (Sabah) - A Birdwatching Tour Naturetrek Tour Report 22 August - 4 September 2009 Golden-naped Barbet, Kinabalu Wallace's Hawk Eagle, Sukau Storm's Stork, Sukau Report compiled by Chris Kehoe Images courtesy of Rainer Seifert Naturetrek Cheriton Mill Cheriton Alresford Hampshire SO24 0NG England T: +44 (0)1962 733051 F: +44 (0)1962 736426 E: [email protected] W: www.naturetrek.co.uk Tour Report Borneo (Sabah) - A Birdwatching Tour Tour Leaders: Chris Kehoe (Naturetrek Leader) Hamit bin Suban (Local guide for main tour) Jason Bugay Reyes (Local guide at Tabin) Osman Assan (Local guide for Mt. Kinabalu) Participants: Main tour only Corinne Shutt Nick Shutt Louise Smiles Mark Smiles Main tour plus Mt. Kinabalu extension Joachim Bayer Janette Lenz Michael Lenz Bryan Nixon Rainer Seifert Raymond Shewan Colin Steer David Stoddard Mt. Kinabalu extension only Moira Hargreaves Roy Hargreaves Day 1 Saturday 22nd August Outbound to Kuala Lumpur Most of the group left Britain on a midday Malaysian Airlines flight to Kuala Lumpur. Although 30 minutes late taking off we more than made up the time and arrived after eleven-and-a-half hours at 07.10 local time (BST+7) the next day, in plenty of time to catch our connecting flight to Sabah. Day 2 Sunday 23rd August Outbound; Sepilok Weather: dry, quite sunny, hot and humid The onward flight to Sandakan via Kota Kinabalu took off on time at 09.20. At Kota Kinabalu we disembarked to carry out Sabah immigration formalities before re-boarding for the final 40 minute leg and arrived on time in Sandakan at 13.20. -

NL1 (Icke-Tättingar) Ver

Nr Vetenskapligt namn Engelskt namn Svenskt namn (noter) 1 STRUTHIONIFORMES STRUTSFÅGLAR 2 Struthionidae Ostriches Strutsar 3 Struthio camelus Common Ostrich struts 4 Struthio molybdophanes Somali Ostrich somaliastruts 5 6 RHEIFORMES NANDUFÅGLAR 7 Rheidae Rheas Nanduer 8 Rhea americana Greater Rhea större nandu 9 Rhea pennata Lesser Rhea mindre nandu 10 11 APTERYGIFORMES KIVIFÅGLAR 12 Apterygidae Kiwis Kivier 13 Apteryx australis Southern Brown Kiwi sydkivi 14 Apteryx mantelli North Island Brown Kiwi brunkivi 15 Apteryx rowi Okarito Kiwi okaritokivi 16 Apteryx owenii Little Spotted Kiwi mindre fläckkivi 17 Apteryx haastii Great Spotted Kiwi större fläckkivi 18 19 CASUARIIFORMES KASUARFÅGLAR 20 Casuariidae Cassowaries, Emu Kasuarer 21 Casuarius casuarius Southern Cassowary hjälmkasuar 22 Casuarius bennetti Dwarf Cassowary dvärgkasuar 23 Casuarius unappendiculatus Northern Cassowary enflikig kasuar 24 Dromaius novaehollandiae Emu emu 25 26 TINAMIFORMES TINAMOFÅGLAR 27 Tinamidae Tinamous Tinamoer 28 Tinamus tao Grey Tinamou grå tinamo 29 Tinamus solitarius Solitary Tinamou solitärtinamo 30 Tinamus osgoodi Black Tinamou svart tinamo 31 Tinamus major Great Tinamou större tinamo 32 Tinamus guttatus White-throated Tinamou vitstrupig tinamo 33 Nothocercus bonapartei Highland Tinamou höglandstinamo 34 Nothocercus julius Tawny-breasted Tinamou brunbröstad tinamo 35 Nothocercus nigrocapillus Hooded Tinamou kamtinamo 36 Crypturellus berlepschi Berlepsch's Tinamou sottinamo 37 Crypturellus cinereus Cinereous Tinamou askgrå tinamo 38 Crypturellus soui -

Predicting and Measuring the Impacts of Climate Change and Habitat Loss on Southeast Asian and Australian Birds

Predicting and measuring the impacts of climate change and habitat loss on Southeast Asian and Australian birds John Berton Chenault Harris Born 9 January 1984, Huntsville, Alabama, USA A thesis submitted to the University of Adelaide, Australia in fulfilment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy 19 October 2012 To my parents. Table of Contents Table of contents………………………………………………………………………..…………I Abstract……………………………………………………………………………...……..…II–III Originality statement……………………………………………………………...……………IV Acknowledgements…………………………………………………………………….…….V–VI Introduction………………………………………………………………………….…….......1–6 Chapter 1. The tropical frontier in avian climate impact research…………………………..7–18 Chapter 2. Using diverse data sources to detect elevational range changes of birds on Mount Kinabalu, Malaysian Borneo…………......................................................19–52 Chapter 3. Will rapid deforestation prevent endemic birds from responding to climate change in Southeast Asia?......................................................................................53–73 Chapter 4. Delay in autumn arrival date of migratory waders and raptors, but not passerines, in the Southeast Asian tropics. .................................................................74–89 Chapter 5. Managing the long-term persistence of a rare cockatoo under climate change………………………………………………………………………......…..90–113 Chapter 6. Conserving imperiled species: a comparison of the IUCN Red List and U.S. Endangered Species Act................................................................ -

Swift As Sound

Swift as sound. Design and evolution of the echolocation system in Swiftlets (Apodidae: Collocaliini) Thomassen, H.A. Citation Thomassen, H. A. (2005, June 16). Swift as sound. Design and evolution of the echolocation system in Swiftlets (Apodidae: Collocaliini). Retrieved from https://hdl.handle.net/1887/3024 Version: Corrected Publisher’s Version Licence agreement concerning inclusion of doctoral thesis in the License: Institutional Repository of the University of Leiden Downloaded from: https://hdl.handle.net/1887/3024 Note: To cite this publication please use the final published version (if applicable). Swift as sound Design and evolution of the echolocation system in Swiftlets (Apodidae: Collocaliini) Henri Thomassen Swift as sound Design and evolution of the echolocation system in Swiftlets (Apodidae: Collocaliini) Thomassen, Hendrik Aalbert Thesis, Leiden University Cover design: Henri Thomassen Illustration from “Brehms Tierleben” (1911) Printed by: Print Partners Ipskamp B.V., Enschede Copyright © Henri Thomassen, 2005 Swift as sound Design and evolution of the echolocation system in Swiftlets (Apodidae: Collocaliini) Proefschrift ter verkrijging van de graad van Doctor aan de Universiteit Leiden, op gezag van de Rector Magnificus Dr. D.D. Breimer, hoogleraar in de faculteit der Wiskunde en Natuurwetenschappen en die der Geneeskunde, volgens besluit van het College voor Promoties te verdedigen op donderdag 16 juni 2005 klokke 16.15 uur door Hendrik Aalbert Thomassen geboren te Harderwijk in 1975 Promotiecommissie Promotor: Prof. dr. G.A. Zweers Copromotor: Dr. G.D.E. Povel Referenten: Prof. dr. W.F.S. Decraemer (Universiteit Antwerpen) Prof. dr. P. de Knijff Overige leden: Prof. dr. J.L. Dubbeldam Prof. dr. E. van der Meijden Prof.