Submission PFR232

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

V8.1 Supported Vehicle List

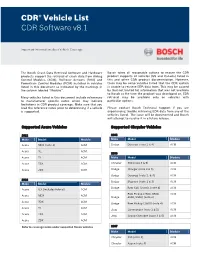

® CDR Vehicle List CDR Software v8.1 Important Information about Vehicle Coverage The Bosch Crash Data Retrieval Software and Hardware Bosch takes all reasonable actions to ensure the CDR products support the retrieval of crash data from Airbag product supports all vehicles (US and Canada) listed in Control Modules (ACM), Roll-over Sensors (ROS) and this and other CDR product documentation. However, Powertrain Control Modules (PCM) installed in vehicles there may be some vehicles listed that the CDR system listed in this document as indicated by the markings in is unable to retrieve EDR data from. This may be caused the column labeled ‘‘Module’’. by (but not limited to) information that was not available to Bosch at the time the product was developed or, EDR Many vehicles listed in this document include references retrieval may be available only on vehicles with to manufacturer specific notes which may indicate particular options. limitations in CDR product coverage. Make sure that you read the reference notes prior to determining if a vehicle Please contact Bosch Technical Support if you are is supported. experiencing trouble retrieving EDR data from any of the vehicles listed. The issue will be documented and Bosch will attempt to resolve it in a future release. Supported Acura Vehicles Supported Chrysler Vehicles 2012 2005 Make Model Module Make Model Module Acura MDX (note 1) ACM Dodge Durango (note 2 & 4) ACM Acura RL ACM 2006 Acura TL ACM Make Model Module Acura TSX ACM Chrysler 300 (note 3 & 5) ACM Acura ZDX ACM Dodge Charger (note -

Chevrolet Caprice 4.3L, 5.7L

GM one wire altenator Used On: (1994-92) Buick LeSabre 3.8L (1994-91) Buick Park Avenue 3.8L (1996-94) Chevrolet Caprice 4.3L, 5.7L (1996) Chevrolet Impala 5.7L (1994-93) Chevrolet Lumina APV Van 3.8L (1994-93) Oldsmobile 88 3.8L (1994-91) Oldsmobile 98 3.8L (1992) Oldsmobile Delta 88 3.8L (1994-93) Oldsmobile Silhouette 3.8L (1994-92) Pontiac Bonneville 3.8L (1994-93) Pontiac Trans Sport 3.8L • 12v hot to fuel solenoid on back of injection pump, negative to ground on engine somewhere, then just hook up the starter and turn it over til it starts. Put some diesel in a tank, keep it higher than the engine, put supply and return fuel lines in it • Easy schmeezy!!! Take the hot wire that goes to the original Sami coil (hopefully it is still there) lengthen it, put an eyelet on it, and voila!!! It's hot when the key is on, therefore energizing the solenoid. On your relay plug base or your actual glow plug relay, you will find a set of numbers. Take a look here at figure #4: http://acmeadapters.com/support_2.php Figure number 4 will show you what wires go where and what wires your missing in your plug end. We'll help you through the wiring. Its not as scary as it seems. For your starter circuit, you need to use your stock samurai wiring harness as is with no modifications: Black wire with a yellow stripe goes to your solonoid on the starter. Fat red wire from the battery goes to your solonoid post with the big nut. -

Travis Hester President and Managing Director GM Canada Travis Hester

Travis Hester President and Managing Director GM Canada Travis Hester was appointed President and Managing Director of GM Canada in April 2018, reporting to Alan Batey, President, GM North America. Prior to his current position, he held the position of Vice President, Global Chief Engineers & Program Management. In that role, he led a team of Executive Chief Engineers and Program Managers overseeing specific groups of vehicles from inception to launch and beyond. This team has responsibility for balancing overall vehicle imperatives including, customer, appearance, manufacturability, material cost, vendor tooling, investment, quality and performance targets. Travis reported to Mark Reuss, GM Executive Vice President, Global Product Development in this role. Prior to this role, Travis was the Executive Chief Engineer for Cadillac Premium Luxury Vehicles and worked exclusively on new Omega architecture derivatives and the Cadillac CT6, a position he held since August 2012. The Cadillac CT6 is known for its many advanced technology breakthroughs including the light weight Mixed Material architecture & world first technologies such as Supercruise and Inside Rear View Camera Mirror. Hester has worked as a resident in the United States twice, China, Australia in addition to architecture development in GM Korea & GM Europe. Currently he is permanent resident at Warren Tech Center, MI USA. In China, Hester worked as the Vehicle Chief Engineer PATAC on vehicles such as the Buick Regal and LaCrosse, along with the Chevrolet Sonic. During this time, he worked on the Regal launch in conjunction with General Motors Europe (GME) and the first PATAC responsible PT Integration in the Global Epsilon platform. He also led the 1st Global Interior Execution on a GM Global Architecture in partnership with GME and GM North America (GMNA) for the LaCrosse. -

The Oakland V-Eightby Tim Dye

The Oakland V-Eightby Tim Dye any of the car enthusiasts you meet flathead V8 motor produced in great numbers M at the average car show today have was introduced by Ford in 1932, and was in never heard of an Oakland. This is under- use for years. Many of these cars survive to- standable since the car was last produced in day, so many in fact that a club exist just for 1931, many years before most of the people them. Members of the Early Ford V8 club at the show were born. With that in mind it can be found at most of the open car shows I is also understandable that they know noth- attend with the Oakland. It is these folks that ing of the unique motor powering the Oak- are most taken aback by the Oakland V8. It is land in its last two years of production, 1930 almost comical how long they will just stand and ‘31. When describing our 1931 Oakland and stare into the engine compartment, and to car enthusiast, they think that it is pretty are always amazed to learn that Oakland had unique, upon mentioning the V8 they auto- a flathead V8 that pre-dates their Fords. matically assume you have a custom car, and The Oakland V8 is a 251 cubic inch motor are quite surprised when you tell them it is that develops 85 horsepower. In comparison, original equipment. the Model “A” had around 40 horsepower, There had been V8s for years, but one of making the Oakland a very racy car in its day. -

Vehicle Make, Vehicle Model

V8, V9 VEHICLE MAKE, VEHICLE MODEL Format: VEHICLE MAKE – 2 numeric VEHICLE MODEL – 3 numeric Element Values: MAKE: Blanks 01-03, 06-10, 12-14, 18-25, 29-65, 69-77, 80-89, 90-94, 98-99 MODEL: Blanks 001-999 Remarks: SEE REMARKS UNDER VEHICLE IDENTIFICATION NUMBER – V12 2009 181 ALPHABETICAL LISTING OF MAKES FARS MAKE MAKE/ NCIC FARS MAKE MAKE/ NCIC MAKE MODEL CODE* MAKE MODEL CODE* CODE TABLE CODE TABLE PAGE # PAGE # 54 Acura 187 (ACUR) 71 Ducati 253 (DUCA) 31 Alfa Romeo 187 (ALFA) 10 Eagle 205 (EGIL) 03 AM General 188 (AMGN) 91 Eagle Coach 267 01 American Motors 189 (AMER) 29-398 Excaliber 250 (EXCL) 69-031 Aston Martin 250 (ASTO) 69-035 Ferrari 251 (FERR) 32 Audi 190 (AUDI) 36 Fiat 205 (FIAT) 33 Austin/Austin 191 (AUST) 12 Ford 206 (FORD) Healey 82 Freightliner 259 (FRHT) 29-001 Avanti 250 (AVTI) 83 FWD 260 (FWD) 98-802 Auto-Union-DKW 269 (AUTU) 69-398 Gazelle 252 (GZL) 69-042 Bentley 251 (BENT) 92 Gillig 268 69-052 Bertone 251 (BERO) 23 GMC 210 (GMC) 90 Bluebird 267 (BLUI) 25 Grumman 212 (GRUM) 34 BMW 191 (BMW) 72 Harley- 253 (HD) 69-032 Bricklin 250 (BRIC) Davidson 80 Brockway 257 (BROC) 69-036 Hillman 251 (HILL) 70 BSA 253 (BSA) 98-806 Hino 270 (HINO) 18 Buick 193 (BUIC) 37 Honda 213 (HOND) 19 Cadillac 194 (CADI) 29-398 Hudson 250 (HUDS) 98-903 Carpenter 270 55 Hyundai 215 (HYUN) 29-002 Checker 250 (CHEC) 08 Imperial 216 (CHRY) 20 Chevrolet 195 (CHEV) 58 Infiniti 216 (INFI) 06 Chrysler 199 (CHRY) 84 International 261 (INTL) 69-033 Citroen 250 (CITR) Harvester 98-904 Collins Bus 270 38 Isuzu 217 (ISU ) 64 Daewoo 201 (DAEW) 88 Iveco/Magirus -

Thule Rapid System Kit 1866

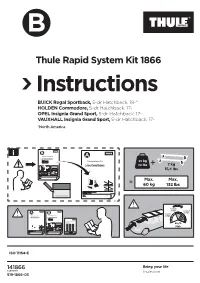

B Thule Rapid System Kit 1866 Instructions BUICK Regal Sportback, 5-dr Hatchback, 18-* HOLDEN Commodore, 5-dr Hatchback, 17- OPEL Insignia Grand Sport, 5-dr Hatchback, 17- VAUXHALL Insignia Grand Sport, 5-dr Hatchback, 17- *North America B i Thule Rapid System Kit xxxx A Instructions Thule Rapid System 754 xx kg 7 kg Thule Rapid System Kit XXXX xx Ibs Thule Rapid System 754 Instructions Instructions Instructions 15,4 Ibs Max. Max. 60 kg 132 Ibs ............. 80 km/h 50 Mph 130 km/h 80 Mph A B 40 km/h Thule Rapid System Kit xxxx Thule Rapid System 754 25 Mph Instructions Instructions 0 Thule Rapid System Kit XXXX Thule Rapid System 754 Instructions Instructions km/h Mph www.thule.com ISO 11154-E 141866 C.20190307 519-1866-03 B Thule Rapid System Kit xxxx Instructions 204 x2 Thule Rapid System Kit XXXX Thule Rapid System 754 Instructions Instructions XXX 1423 x4 x1 206 x2 x1 1 X (scale) X (mm) X (inch) BUICK Regal Sportback, 5-dr Hatchback, 18-* 44 1091 43 HOLDEN Commodore, 5-dr Hatchback, 17- 44 1091 43 OPEL Insignia Grand Sport, 5-dr Hatchback, 17- 44 1091 43 VAUXHALL Insignia Grand Sport, 5-dr Hatchback, 17- 44 1091 43 A 2 Thule Rapid System 754 Instructions X X/Y Y Y (scale) Y (mm) Y (inch) 5-dr Hatchback, 18-* 3 BUICK Regal Sportback, 41 1061 41 /4 5-dr Hatchback, 17- 3 HOLDEN Commodore, 41 1061 41 /4 5-dr Hatchback, 17- 3 OPEL Insignia Grand Sport, 41 1061 41 /4 5-dr Hatchback, 17- 3 VAUXHALL Insignia Grand Sport, 41 1061 41 /4 2 519-1866-03 2 BUICK Regal Sportback, 5-dr Hatchback, 18-* HOLDEN Commodore, 5-dr Hatchback, 17- OPEL Insignia -

Pontiac Hood Ornaments: Chief of the Sixes

so prominently in the news since Pontiac’s ornaments are among the most striking from the fl amboyant era of the American automobile. In the early 1930s they were shaped in the form of a Native American head adorned with feathered headdress, but by the 1950s they had morphed into the memorable confi guration of jet plane with the head of Chief Pontiac at the helm. These beautiful and iconic designs caught the public imagination then and now, but, when contextualized to their own day, their signifi cance expands. They can be understood as ciphers of industrial strength in the face of the complex and troubled situation for the Native American in postwar America. The fl ying mascot’s sleek body trailing behind the bold, simplifi ed features of Chief Pontiac is replete with glistening surface and tapering forms. Its swept wings were modeled after the jet aircraft of the period and in that regard symbolized the military might embodied in the Cold War fi ghters and bomber planes. In the words of one designer, “We liked jet airplanes, we liked fl ashiness, we liked power.”1 At work was a language of corporate power and machismo linked as much to planes as to tropes of the Native American male body.2 As the Indian body converts into its technological other, Pontiac’s ornament appropriates the raw power of the myth of the savage body so associated with the Indian warrior, and transforms it into a streamlined extension of the car’s force as moving energy. Indeed, the cultural stereotype of the Pontiac Hood Ornaments Chief of the Sixes By Mona Hadler General Motors’ recent announcement of the impending closing of its Pontiac division made a stir across America where the car had been a staple for generations. -

D-231-44.Pdf

State of California AIR RESOURCES BOARD EXECUTIVE ORDER D-231-44 Relating to Exemptions Under Section 27156 of the California Vehicle Code Whipple Industries, Inc. Whipple Supercharger Pursuant to the authority vested in the Air Resources Board by Section 27156 of the Vehicle Code; and Pursuant to the authority vested in the undersigned by Section 39515 and Section 39516 of the Health and Safety Code and Executive Order G-14-012; IT IS ORDERED AND RESOLVED: That the installation of the Whipple Supercharger, manufactured and marketed by Whipple Industries, Inc., 3292 N. Weber, Fresno California 93722, has been found not to reduce the effectiveness of the applicable vehicle pollution control systems and, therefore, is exempt from the prohibitions of Section 27156 of the Vehicle Code for the following General Motors vehicles listed in Exhibit A The Whipple Supercharger consists of the following main components: A 2.3L or a 2.9L displacement twin screw supercharger, intake manifold, bypass valve, high flow injectors, intercooler, reflashed ECM, air inlet tubing, and an electronic fuel pump booster. Boost is limited to 11 pounds per square inch. The stock crankshaft pulley, throttlebody, thermostat, air filter housing (except 1999 to 2003 model year trucks), and mass air flow sensor are retained. Modifications may be made to the stock air intake system that is before the stock air filter box. All supplied fuel hoses are either Avon's CADbar 9000 series or a stock factory replacement, and fuel and vapor line connectors supplied with the kit are OEM equivalent parts. Breather hoses may be replaced with an SAE30R9 rated hose. -

Stevenson Motor Co. Inc. 1207 Levee Street 789 Telephone» ♦ * « * Quality at Low Cost

closed line. The exterior body panels, eaily in the spring, rolling of steel in Church on wheels and hood are in the new Ban the 14-inch merchant mill has been un- IN THE disc BobbuMp SHADOWS color. body stripes derway for several weeks. Arizona gray The Causes rear Women’s Revolt new SIX CHEVROLET IS are in The leather-covered m )OUTLOOK At Dearborn the engineering PONTIAC gold. with its landau windows and laboratory was completed early in the quarter .landau bars adds a final touch year and already work has begun on graceful DUBLIN—Declaring that the lent*11 of the car. The gray of their hair is an extensive addition to this building, to the appearance not a putter involflif of the interior harmonizes with the their increasing the floor spa* e 60,000 square, religion, nine young women colors. The landau in- feet. Additions and alterations also outside pan^l bers of the parish church at Gweed«*e, includes dash and have been made to the power house and terior equipment County Donegal, have notified the pas- roller shades, foot rest, heating plant. dome lights, tor, Rev. David Kerr, that they will Hot Big Expansion Program General Motors Models Put set and door pockets. While only minor extension New New Closed robe rail, smoking abide by his prohibition of bobbed 1 building .hgir. T/ie coupe is finished in the Arizona He, in has to Continue During and change* were made at the High- Product to be Shown on in New turn, informed them there Display Duco. -

Acdelco Premium Belt Range

ACDELCO PREMIUM BELT RANGE ACDELCO BELTS ACDelco P/N GM P/N Application Make/Model FORD (Asia & Oceania) Telstar 2.0 / FORD Australia Laser 1.8 / HONDA Integra 1.8 / MAZDA 323 1.8 / MAZDA 323 Astina 1.8 / MAZDA 323 Protege 1.8 / MAZDA 626 2.0 / MAZDA 626 Estate/Wagon 2.0 / MAZDA 4PK920 19376034 Capella 2.0 / MAZDA Familia 1.8 / MAZDA MX6 2.5 / MAZDA Premacy 1.8 / NISSAN Pulsar 2.0 / SUZUKI Alto 1.0 / SUZUKI Cultus 1.0 / TOYOTA Chaser 2.0 / TOYOTA Echo 1.3 / TOYOTA Starlet 1.3 / TOYOTA Supra 3.0 / TOYOTA Yaris 1.3 / TOYOTA Yaris Verso 1.3 FORD (Europe) Fiesta 1.2 / FORD (Europe) Fusion 1.4 / FORD Australia Fiesta 5PK692SF 19375735 1.6 / MAZDA 3 2.0 / MAZDA Axela 2.0 LEXUS ES 300 3.0 / LEXUS RX 300 3.0 / LEXUS RX 330 3.3 / MITSUBISHI Lancer 1.5 / MITSUBISHI Mirage 1.3 / NISSAN 200SX 2.0 / NISSAN 4PK880 19376031 Serena 2.0 / NISSAN Skyline GT-R 2.6 / TOYOTA Avalon 3.0 / TOYOTA Camry 3.0 / TOYOTA Estima 3.0 / TOYOTA Harrier 3.0 / TOYOTA Hiace 2.4 / TOYOTA Kluger 3.3 / TOYOTA Starlet 1.3 HOLDEN Calais 3.6 / HOLDEN Caprice 3.6 / HOLDEN Commodore 3.6 / HOLDEN Crewman 3.6 / HOLDEN Frontera 2.2 / HOLDEN One Tonner 3.6 6PK2045 19376030 / HOLDEN Statesman 3.6 / JEEP Cherokee 3.2 / SUZUKI Grand Vitara 2.4 / SUZUKI SX4 2.0 DAEWOO 1.5i 1.5 / DAEWOO Cielo 1.5 / DAEWOO Lanos 1.5 / HOLDEN Nova 1.4 / SUZUKI Vitara 1.4 / TOYOTA Corolla 1.3 / TOYOTA 5PK970 19376037 Corolla Estate/Wagon 1.6 / TOYOTA Corolla Levin 1.5 / TOYOTA Sprinter 1.6 / TOYOTA Sprinter Carib 1.6 MAZDA 3 2.0 / MAZDA CX3 2.0 / MAZDA CX5 2.0 / MITSUBISHI Galant 6PK965 19376038 2.5 / MITSUBISHI -

Shannon Galichowski and the Same Shannon Galichowski in Her

Galichowski v. Shaw GMC Pontiac Buick Hummer Ltd., 2009 ABCA 390, 2009... 2009 ABCA 390, 2009 CarswellAlta 2019, [2010] 3 W.W.R. 609, [2010] A.W.L.D. 257... 2009 ABCA 390 Alberta Court of Appeal Galichowski v. Shaw GMC Pontiac Buick Hummer Ltd. 2009 CarswellAlta 2019, 2009 ABCA 390, [2010] 3 W.W.R. 609, [2010] A.W.L.D. 257, [2010] A.W.L.D. 258, [2010] A.W.L.D. 297, 17 Alta. L.R. (5th) 215, 183 A.C.W.S. (3d) 977, 469 A.R. 156, 470 W.A.C. 156, 65 B.L.R. (4th) 100, 90 M.V.R. (5th) 60 Shannon Galichowski and the same Shannon Galichowski in her capacity as Administrator of the Estate of Russell Galichowski and in her capacity as Next Friend of Megan Rose Galichowski, an infant and Joseph Galichowski and Sonja Galichowski (Not Parties to the Appeal / Plaintiffs) Shaw GMC Pontiac Buick Hummer Ltd. (Appellant / Defendant) and Polaris Explorer Ltd. (Respondent / Defendant) and The Public Trustee as nominal Administrator Ad Litem of the Estate of John Scott MacDonald (Not a Party to the Appeal / Defendant) Elizabeth McFadyen, Peter Martin, J.D. Bruce McDonald JJ.A. Heard: November 6, 2009 Judgment: December 14, 2009 Docket: Calgary Appeal 0901-0056-AC Proceedings: reversing Galichowski v. Shaw GMC Pontiac Buick Hummer Ltd. (2008), 2008 ABQB 673, 2008 CarswellAlta 1698, 52 B.L.R. (4th) 137, 1 Alta. L.R. (5th) 314, 459 A.R. 221, [2009] 6 W.W.R. 181, 75 M.V.R. (5th) 214 (Alta. Q.B.) Counsel: D.K. -

MY10 VE and WM PRODUCT INFORMATION 3.0L and 3.6L SIDI

September 2009 MY10 VE and WM PRODUCT INFORMATION 3.0L and 3.6L SIDI V6 Engines Overview The Global V6 engine family was launched by General Motors in 2003 to fulfil its strategy to build a new generation of engines for flexible worldwide application in premium and high- performance vehicles. Today GM Powertrain’s all-alloy 60-degree double overhead cam (DOHC) Global V6 engines power a variety of vehicles around the world. GM Holden is a producer as well as a user of Global V6 engines. In 2003 its newly commissioned $400 million Port Melbourne V6 engine plant began building Global V6 engines for export. In August 2004 Alloytec Global V6 engines were introduced to the Australian market with the Holden VZ Commodore and WL Caprice and Statesman model ranges. The latest evolution of the Global V6 is the Spark Ignition Direct Injection SIDI V6; which offers advanced direct combustion chamber fuel injection. Like its predecessor, the SIDI V6 applies highly developed engine technologies such as state-of- the-art casting processes, full four-cam phasing, ultra-fast data processing and torque-based engine management. GM Holden engineers jointly assisted in the architectural development of the SIDI V6 with colleagues from GM technical centres in North America and Germany. The 3.0L and 3.6L SIDI V6 engines introduced with the MY10 Holden Commodore, Berlina, Calais, Sportwagon, Ute, Statesman and Caprice model ranges combine with smooth-shifting six-speed automatic transmission and dual exhaust specified as standard*. They deliver a balance of improved operating refinement with first-rate noise and vibration control, good specific output, high torque over a broad rpm band, fuel economy and low emissions, exclusive durability-enhancing features and very low maintenance.