British Relations with the Cis-Sutlej States 1809-1823

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

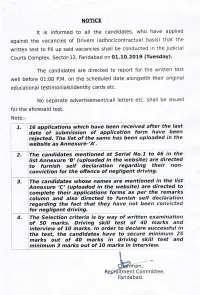

DRIVER LIST and NOTICE for WRITTEN EXAMINATION.Pdf

COMBINE Annexure-A Reject List of applications for the post of Driver August -2019 ( Ad-hoc) as received after due date 20/08/19 Date of Name of Receipt No. Father's / Husband Name Address of the candidate Contact No. Date of Birth Remarks Receipt Candidate Vill-Manesar, P.O Garth Rotmal Application 1 08/21/19 Yogesh Kumar Narender Kumar Teh- Ateli Distt Mohinder Garh 10/29/93 Received after State Haryana 20.08.2019 Khor PO Ateli Mandi Teh Ateli, Application 2 08/21/19 Pankaj Suresh Kumar 9818215697 12/20/93 Received after distt mahendergarh 20.08.2019 Amarjeet S/O Krishan Kumar Application 3 08/21/19 Amarjeet Kirshan Kumar 05/07/92 Received after VPO Bhikewala Teh Narwana 20.08.2019 121, OFFICER Colony Azad Application 4 08/21/19 Bhal Singh Bharat Singh nagar Rajgarh Raod, Near 08/14/96 Received after Godara Petrol Pump Hissar 20.08.2019 Vill Hasan, Teh- Tosham Post- Application 5 08/21/19 Rakesh Dharampal 10/15/97 Received after Rodhan (Bhiwani) 20.08.2019 VPO Jonaicha Khurd, Teh Application 6 08/21/19 Prem Shankar Roshan Lal Neemarana, dist Alwar 12/30/97 Received after (Rajasthan) 20.08.2019 VPO- Bhikhewala Teh Narwana Application 7 08/21/19 Himmat Krishan Kumar 09/05/95 Received after Dist Jind 20.08.2019 vill parsakabas po nagal lakha Application 8 08/21/19 Durgesh Kumar SHIMBHU DAYAL 09/05/95 Received after teh bansur dist alwar 20.08.2019 RZC-68 Nihar Vihar, Nangloi New Application 9 08/26/19 Amarjeet Singh Mohinder Singh 03/17/92 Received after Delhi 20.08.2019 Vill Palwali P.O Kheri Kalan Sec- Application 10 08/26/19 Rohit Sharma -

The Kalinga Collection of Nazarana Coins Auction 41

The Kalinga Collection of Nazarana Coins Auction 41 10 Sep. 2015 | The Diplomat Highlight of Auction 39 63 64 133 111 90 96 97 117 78 103 110 112 138 122 125 142 166 169 Auction 41 The Kalinga Collection of Nazarana Coins (with Proof & OMS Coins) Thursday, 10th September 2015 7.00 pm onwards VIEWING Noble Room Monday 7 Sept. 2015 11:00 am - 6:00 pm The Diplomat Hotel Behind Taj Mahal Palace, Tuesday 8 Sept. 2015 11:00 am - 6:00 pm Opp. Starbucks Coffee, Wednesday 9 Sept. 2015 11:00 am - 6:00 pm Apollo Bunder At Rajgor’s SaleRoom Mumbai 400001 605 Majestic Shopping Centre, Near Church, 144 JSS Road, Opera House, Mumbai 400004 Thursday 10 Sept. 2015 3:00 pm - 6:30 pm At the Diplomat Category LOTS Coins of Mughal Empire 1-75 DELIVERY OF LOTS Coins of Independent Kingdoms 76-80 Delivery of Auction Lots will be done from the Princely States of India 81-202 Mumbai Office of the Rajgor’s. European Powers in India 203-236 BUYING AT RAJGOR’S Republic of India 237-245 For an overview of the process, see the Easy to buy at Rajgor’s Foreign Coins 246-248 CONDITIONS OF SALE Front cover: Lot 111 • Back cover: Lot 166 This auction is subject to Important Notices, Conditions of Sale and to Reserves To download the free Android App on your ONLINE CATALOGUE Android Mobile Phone, View catalogue and leave your bids online at point the QR code reader application on your www.Rajgors.com smart phone at the image on left side. -

Colonial and Post-Colonial Origins of Agrarian Development: the Case of Two Punjabs

University of Massachusetts Amherst ScholarWorks@UMass Amherst Doctoral Dissertations Dissertations and Theses November 2016 Colonial and Post-Colonial Origins of Agrarian Development: The Case of Two Punjabs Shahram Azhar University of Massachusetts Amherst Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarworks.umass.edu/dissertations_2 Part of the Economic History Commons, Growth and Development Commons, and the Political Economy Commons Recommended Citation Azhar, Shahram, "Colonial and Post-Colonial Origins of Agrarian Development: The Case of Two Punjabs" (2016). Doctoral Dissertations. 726. https://doi.org/10.7275/9043142.0 https://scholarworks.umass.edu/dissertations_2/726 This Open Access Dissertation is brought to you for free and open access by the Dissertations and Theses at ScholarWorks@UMass Amherst. It has been accepted for inclusion in Doctoral Dissertations by an authorized administrator of ScholarWorks@UMass Amherst. For more information, please contact [email protected]. THE COLONIAL AND POST COLONIAL ORIGINS OF AGRARIAN DEVELOPMENT: A CASE OF TWO PUNJABS A Dissertation Presented By SHAHRAM AZHAR Submitted to the Graduate School of the University of Massachusetts Amherst in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY September 2016 Economics © Copyright by Shahram Azhar 2016 All Rights Reserved THE COLONIAL AND POST COLONIAL ORIGINS OF AGRARIAN DEVELOPMENT: A CASE OF TWO PUNJABS A Dissertation Presented by SHAHRAM AZHAR Approved as to style and content by: ___________________________________________ Mwangi wa Gĩthĩnji, Co-Chair ___________________________________________ Deepankar Basu, Co-Chair ___________________________________________ Priyanka Srivastava, Member ___________________________ Michael Ash, Department Chair Economics For Stephen Resnick; a teacher, mentor, and comrade. i ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS This study owes a debt to many people from different parts of the world. -

2012 Vol.1 Part I, II, III & IV Contents, Index, Reference and Title

(ii) (i) (iii) (iv) (v) (vi) (vii) (viii) (x) (ix) (xi) (xii) (xiv) (xiii) (xvi) (xv) (xviii) (xvii) (xx) CONTENTS Balwinder Singh and Ors.; State of Punjab v. .... 45 A.V.M. Sales Corporation v. M/s. Anuradha Bavo @ Manubhai Ambalal Thakore v. State Chemicals Pvt. Ltd. .... 318 of Gujarat .... 822 Absar Alam @ Afsar Alam v. State of Bihar .... 890 Bhanot (V.D.) v. Savita Bhanot .... 867 Alister Anthony Pareira v. State of Maharashtra .... 145 Bhartiya Khadya Nigam Karmchari Sangh & Anr.; Food Corporation of India & Ors. v..... 230 Ambrish Tandon & Anr.; State of U.P. & Ors. v. .... 422 Bheru Singh & Ors.; State of Madhya Pradesh Amit v. State of Uttar Pradesh .... 1009 & Anr. v. .... 535 Ansaldo Caldaie Boilers India P. Ltd. & Anr.; Bishnu Deo Bhandari; Mangani Lal Mandal v. .... 527 NTPC Limited v. .... 966 Brundaban Gouda & Anr.; Joshna Gouda v. .... 464 Anuradha Chemicals Pvt. Ltd. (M/s.); A.V.M. Sales Corporation v. .... 318 Burdwan Central Cooperative Bank Ltd. & Anr. v. Asim Chatterjee & Ors. .... 390 Archaeological Survey of India v. Narender Anand and others .... 260 C.B.I., Delhi & Anr.; Dr. Mrs. Nupur Talwar v. .... 31 Arup Das & Ors. v. State of Assam & Ors. .... 445 Chandra Narain Tripathi; Kapil Muni Karwariya v. .... 956 Asim Chatterjee & Ors.; Burdwan Central Cooperative Bank Ltd. & Anr. v. .... 390 Commissioner of Central Excise, U.P.; (M/s.) Flex Engineering Limited v. .... 209 Assam Urban Water Supply & Sew. Board v. Subash Projects & Marketing Ltd. .... 403 Commnr. of Central Excise, Faridabad v. M/s Food & Health Care Specialities & Anr. .. 908 Assistant Commissioner of Commercial Taxes & Anr.; Hotel Ashoka (Indian Tour. -

The Sikh Religion by Macauliffe, Volume IV, Pages 293 to 295 : " Phul Was Contemporary of Guru Har Rai, the Seventh Sikh Guru

^ f • cv* cQ ** > <? LO CO PUNJ VB THE HOMELAND OF THE SIKHS together with THE SIKH MEMORANDUM to THE SAPRU CONCILIATION COMMITTEE by HARNAM SINGH 1945 Price Rs. 2/ \ > I \ / I I 1 FOREWORD The reader will find in the pages of this book a compre hensive account of the case of the Sikh community in refer ence to the political problems that confront India to-day. The besetting complexities of the situation are recognised on all hands. What strikes the Sikhs as most unfortunate is that in almost every attempt at a solution—official or non- official—so far made, their case has not been given the weight it undoubtedly deserves. This book is an attempt to put the Sikh case as clearly as possible in a helpful spirit. The book is divided into two parts. The first part of the book gives a documented narrative of the position, rights and claims of the Sikh community in the Punjab—the province of their birth and history. An account of the adjoining States, relevant to such interests, is also included. The author has examined the population figures in the light of the Census Reports and has arrived at intriguing conclusions. His views should provoke a more scientific study of the reality of Muslim claims on the Punjab on the basis of their population strength. The second part is the text of the Sikh Memorandum submitted to the Sapru Conciliation Committee. It is signed by Sikhs belonging to every school of thought in public, (social and religious life. Never before, it can be freely stated, has there been such unanimity of opinion amongst Sikhs. -

Bilateral Relations Between India and Pakistan, 1947- 1957

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by Apollo THE FINALITY OF PARTITION: BILATERAL RELATIONS BETWEEN INDIA AND PAKISTAN, 1947- 1957 Pallavi Raghavan St. Johns College University of Cambridge This dissertation is submitted for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy. Faculty of History University of Cambridge September, 2012. 1 This dissertation is the result of my own work, includes nothing which is the outcome of work done in collaboration, and falls within the word limit granted by the Board of Graduate Studies, University of Cambridge. Pallavi Raghavan 2 ABSTRACT This dissertation will focus on the history of bilateral relations between India and Pakistan. It looks at how the process of dealing with issues thrown up in the aftermath of partition shaped relations between the two countries. I focus on the debates around the immediate aftermath of partition, evacuee property disputes, border and water disputes, minorities and migration, trade between the two countries, which shaped the canvas in which the India-Pakistan relationship took shape. This is an institution- focussed history to some extent, although I shall also argue that the foreign policy establishments of both countries were also responding to the compulsions of internal politics; and the policies they advocated were also shaped by domestic political positions of the day. In the immediate months and years following partition, the suggestions of a lastingly adversarial relationship were already visible. This could be seen from not only in the eruption of the Kashmir dispute, but also in often bitter wrangling over the division of assets, over water, numerous border disputes, as well as in accusations exchanged over migration of minorities. -

The Sikh Dilemma: the Partition of Punjab 1947

The Sikh Dilemma: The Partition of Punjab 1947 Busharat Elahi Jamil Abstract The Partition of India 1947 resulted in the Partition of the Punjab into two, East and West. The 3rd June Plan gave a sense of uneasiness and generated the division of dilemma among the large communities of the British Punjab like Muslims, Hindus and Sikh besetting a holocaust. This situation was beneficial for the British and the Congress. The Sikh community with the support of Congress wanted the proportion of the Punjab according to their own violation by using different modules of deeds. On the other hand, for Muslims the largest populous group of the Punjab, by using the platform of Muslim League showed the resentment because they wanted the decision on the Punjab according to their requirements. Consequently the conflict caused the world’s bloodiest partition and the largest migration of the history. Introduction The Sikhs were the third largest community of the United Punjab before India’s partition. The Sikhs had the historic religious, economic and socio-political roots in the Punjab. Since the annexation of the Punjab, they were faithful with the British rulers and had an influence in the Punjabi society, even enjoying various privileges. But in the 20th century, the Muslims 90 Pakistan Vision Vol. 17 No. 1 Independence Movement in India was not only going to divide the Punjab but also causing the division of the Sikh community between East and West Punjab, which confused the Sikh leadership. So according to the political scenarios in different timings, Sikh leadership changed their demands and started to present different solutions of the Sikh enigma for the geographical transformation of the province. -

Education in the Phulkian States R.S. Gurna , Khanna

P: ISSN NO.: 2394-0344 RNI No.UPBIL/2016/67980 VOL-1* ISSUE-10* January- 2017 E: ISSN NO.: 2455-0817 Remarking An Analisation Education in the Phulkian States Abstract The question of education has been one of those live problems which always aroused passion of interest in India. The Phulkian rulers made progressive efforts in this direction. First regular school was opened in Patiala in 1860 and in 1870 regular department of education was established. Primary education was made free in the state in 1911. Alongside of the primary education the scope of middle and high school education was also enlarges. Patiala was among the first few cities of the Punjab which could legitimately boast of a degree college. The first notable attempt at modernising education in the Nabha State was made by Raja Bharpur Singh in 1863 A.D. when he established a school in Nabha itself with one teacher for English and another for Arabic and Persion. In 1890 a separate cantonment school at Nabha was opened in which English, Gurumukhi, Persian and other subjects were taught. In Nabha State by 1917, the number rose to 15 schools for boys and two for girls. Attention was also paid towards adult education and technical education. Scholarships and stipends were introduced to encourage promising students of the state to acquire college education. Similarly in Jind State, the number of primary schools rose to 47 in 1945, Maharaja Ranbir Singh had made primary education free in the schools of the State since 1912. The rulers of the Phulkian States of Patiala, Nabha, and Jind showed enough interest in the development of education in their respective states. -

ORIENTAL BANK of COMMERCE.Pdf

STATE DISTRICT BRANCH ADDRESS CENTRE IFSC CONTACT1 CONTACT2 CONTACT3 MICR_CODE D NO 10-86, MAIN RD, OPP MUNICIPAL CORPORATION, ANDHRA MANCHERIAL, MANCHERIY 011- PRADESH ADILABAD MANCHERIAL ANDHRA PRADESH AL ORBC0101378 23318423 12-2-990, PLOT NO 66, MAIN ROAD, ANDHRA SAINAGAR, ANANTAPU 040- PRADESH ANANTAPUR ANANTHAPUR ANANTHAPUR R ORBC0101566 23147010 D.NO.383,VELLORE ROAD, ANDHRA GRAMSPET,CHITTOO 970122618 PRADESH CHITTOOR CHITTOOR R-517002 CHITTOOR ORBC0101957 5 EC ANDHRA TIRUMALA,TIRU TTD SHOPPING 0877- PRADESH CHITTOOR PATI COMPLEXTIRUMALA TIRUPATI ORBC0105205 2270340 P.M.R. PLAZA, MOSQUE ROADNEAR MUNICIPAL ANDHRA OFFICETIRUPATI, 0877- PRADESH CHITTOOR TIRUPATI A.P.517501 TIRUPATI ORBC0100909 2222088 A P TOURISM HOTEL COMPOUND, OPP S P 08562- ANDHRA BUNGLOW,CUDDAPA 255525/255 PRADESH CUDDAPAH CUDDAPAH H,PIN - 516001 CUDDAPAH ORBC0101370 535 D.NO 3-2-1, KUCHI MANCHI AMALAPURAM, AGRAHARAM, BANK ANDHRA EAST DIST:EAST STREET, DISTT: AMALAPUR 08856- PRADESH GODAVARI GODAVARI EAST GODAVARI , AM ORBC0101425 230899 25-6-40, GROUND FLOORGANJAMVARI STREET, KAKINADADIST. ANDHRA EAST EAST GODAVARI, 0884- PRADESH GODAVARI KAKINADA A.P.533001 KAKINADA ORBC0100816 2376551 H.NO.13-1-51 ANDHRA EAST GROUND FLOOR PRADESH GODAVARI KAKINADA MAIN ROAD 533 001 KAKINADA ORBC0101112 5-8-9,5-8-9/1,MAIN ROAD, BESIDE VANI MAHAL, MANDAPETA, DISTT. ANDHRA EAST EAST GODAVARI, PIN MANDAPET 0855- PRADESH GODAVARI MANDAPETA - 533308 A ORBC0101598 232900 8-2A-121-122, DR. M. GANGAIAHSHOPPIN G COMPLEX, MAIN ANDHRA EAST ROADRAJAHMUNDR RAJAHMUN 0883- PRADESH GODAVARI -

Annual Report of CONCOR for FY 2015-16

fe'ku ^^gekjk fe'ku vius O;kolkf;d lg;ksfx;ksa vkSj 'ks;j/kkjdksa ds lkFk feydj dkWudkWj dks ,d mRÑ"V daiuh cukus dk gSA vius O;kolkf;d lg;ksfx;ksa ds lfØ; lg;ksx ls rFkk ykHkiznrk ,oa o`f) lqfuf'pr djds vius xzkgdksa dks vuqfØ;k'khy] ykxr izHkkoh] n{k vkSj fo'oluh; laHkkjra= lk/ku miyC/k djkdj ge vo'; gh ,slk dj ik,axsA ge vius xzkgdksa dh igyh ilan cus jgus ds fy, iz;kljr gSaA ge vius lkekftd nkf;Roksa ds izfr n`<+rkiwoZd izfrc) gSa vkSj ge ij tks fo'okl j[kk x;k gS] ml ij [kjs mrjsaxsA^^ MISSION "Our mission is to join with our community partners and stake holders to make CONCOR a company of outstanding quality. We do this by providing responsive, cost effective, efficient and reliable logistics solutions to our customers through synergy with our community partners and ensuring profitability and growth. We strive to be the first choice for our customers. We will be firmly committed to our social responsibility and prove worthy of trust reposed in us." 01 y{; Þge xzkgd dsafnzr] fu"iknu izsfjr] ifj.kkeksUeq[l laxBu cusaxs ftldk eq[; y{; xzkgdksa dks izfrykHk fnykuk gksxkA^^ Þge lalk/kuksa dk ykHkizn miHkksx djus gsrq rFkk mPp xq.koÙkk okyh lsok,a nsus ds fy, iz;kljr jgsaxs vkSj Js"Brk gsrq ekud LFkkfir djus ds :i esa gekjh igpku gksxhA^^ Þge ifj"d`r uohu lsok,a nsus ds fy, fujUrj u, vkSj csgrj fodYi [kkstsaxsA xzkgdksa dh lqfo/kk vkSj larqf"V gh gekjk /;s; gksxkA ge vius O;kolkf;d izfrLikf/kZ;ksa ls lh[k ysaxs vkSj Js"Brk gsrq lnSo iz;kljr jgsaxsA^^ Þge vius laxBu ds y{;ksa vkSj fe'ku ds leFkZu eas ifjes; fu"iknu y{; fu/kkZfjr djsaxsA -

Punjab's Muslims

63 Anna Bigelow: Punjab’s Muslims Punjab’s Muslims: The History and Significance of Malerkotla Anna Bigelow North Carolina State University ____________________________________________________________ Malerkotla’s reputation as a peaceful Muslim majority town in Punjab is overall true, but the situation today is not merely a modern extension of the past reality. On the contrary, Malerkotla’s history is full of the kind of violent events and complex inter-religious relations more often associated with present-day communal conflicts. This essay is a thick description of the community and culture of Malerkotla that has facilitated the positive inter-religious dynamics, an exploration of the histories that complicate the ideal, and an explanation of why Malerkotla has successfully managed stresses that have been the impetus for violence between religions in South Asia. ________________________________________________________ When the Punjabi town of Malerkotla appears in the news, it is often with headlines such as “Malerkotla: An Island of Peace,” (India Today, July 15, 1998), or “Malerkotla Muslims Feel Safer in India,” (Indian Express, August 13, 1997), or “Where Brotherhood is Handed Down as Tradition” (The Times of India, March 2, 2002). These headlines reflect the sad reality that a peaceful Muslim majority town in Indian Punjab is de facto newsworthy. This is compounded by Malerkotla’s symbolic importance as the most important Muslim majority town in the state, giving the area a somewhat exalted status.1 During a year and a half of research I asked residents whether the town’s reputation as a peaceful place was true and I was assured by most that this reputation is not merely a media or politically driven idealization of the town. -

Punjab Board Class 9 Social Science Textbook Part 1 English

SOCIAL SCIENCE-IX PART-I PUNJAB SCHOOL EDUCATION BOARD Sahibzada Ajit Singh Nagar © Punjab Government First Edition : 2018............................ 38406 Copies All rights, including those of translation, reproduction and annotation etc., are reserved by the Punjab Government. Editor & Co-ordinator Geography : Sh. Raminderjit Singh Wasu, Deputy Director (Open School), Punjab School Education Board. Economics : Smt. Amarjit Kaur Dalam, Deputy Director (Academic), Punjab School Education Board. WARNING 1. The Agency-holders shall not add any extra binding with a view to charge extra money for the binding. (Ref. Cl. No. 7 of agreement with Agency-holders). 2. Printing, Publishing, Stocking, Holding or Selling etc., of spurious Text- book qua text-books printed and published by the Punjab School Education Board is a cognizable offence under Indian Penal Code. Price : ` 106.00/- Published by : Secretary, Punjab School Education Board, Vidya Bhawan Phase-VIII, Sahibzada Ajit Singh Nagar-160062. & Printed by Tania Graphics, Sarabha Nagar, Jalandhar City (ii) FOREWORD Punjab School Education Board, has been engaged in the endeavour to prepare textbooks for all the classes at school level. The book in hand is one in the series and has been prepared for the students of class IX. Punjab Curriculum Framework (PCF) 2013 which is based on National Curriculum Framework (NCF) 2005, recommends that the child’s life at school must be linked to their life outside the school. The syllabi and textbook in hand is developed on the basis of the principle which makes a departure from the legacy of bookish learning to activity-based learning in the direction of child-centred system.