BAKHSHISH SINGH NIJJAR M.A., Ph.D

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

1. Raja of Princely State Fled to the Mountain to Escape Sikh Army's

1 1. Raja of princely state fled to the mountain to escape Sikh army’s attack around 1840 AD? a) Mandi b) Suket c) kullu d) kehlur 2. Which raja of Nurpur princely State built the Taragarh Fort in the territory of Chamba state? a) Jagat Singh b) Rajrup Singh c) Suraj Mal d) Bir Singh 3. At which place in the proposed H.P judicial Legal Academy being set up by the H.P. Govt.? a) Ghandal Near Shimla b) Tara Devi near Shimla c) Saproon near Shimla d) Kothipura near Bilaspur 4. Which of the following Morarian are situated at keylong, the headquarter of Lahul-Spiti districts of H.P.? CHANDIGARH: SCO: 72-73, 1st Floor, Sector-15D, Chandigarh, 160015 SHIMLA: Shushant Bhavan, Near Co-operative Bank, Chhota Shimla 2 a) Khardong b) Shashpur c) tayul d) All of these 5. What is the approximately altitude of Rohtang Pass which in gateway to Lahul and Spiti? a) 11000 ft b) 13050 ft c) 14665 ft d) 14875 ft 6. Chamba princely state possessed more than 150 Copper plate tltle deads approximately how many of them belong to pre-Mohammedan period? a) Zero b) Two c) five d) seven 7. Which section of Gaddis of H.P claim that their ancestors fled from Lahore to escape persecution during the early Mohammedan invasion? a) Rajput Gaddis b) Braham in Gaddis CHANDIGARH: SCO: 72-73, 1st Floor, Sector-15D, Chandigarh, 160015 SHIMLA: Shushant Bhavan, Near Co-operative Bank, Chhota Shimla 3 c) Khatri Gaddis d) None of these 8. Which of the following sub-castes accepts of firing in the name of dead by performing the death rites? a) Bhat b) Khatik c) Acharaj d) Turi’s 9. -

Section 124- Unpaid and Unclaimed Dividend

Sr No First Name Middle Name Last Name Address Pincode Folio Amount 1 ASHOK KUMAR GOLCHHA 305 ASHOKA CHAMBERS ADARSHNAGAR HYDERABAD 500063 0000000000B9A0011390 36.00 2 ADAMALI ABDULLABHOY 20, SUKEAS LANE, 3RD FLOOR, KOLKATA 700001 0000000000B9A0050954 150.00 3 AMAR MANOHAR MOTIWALA DR MOTIWALA'S CLINIC, SUNDARAM BUILDING VIKRAM SARABHAI MARG, OPP POLYTECHNIC AHMEDABAD 380015 0000000000B9A0102113 12.00 4 AMRATLAL BHAGWANDAS GANDHI 14 GULABPARK NEAR BASANT CINEMA CHEMBUR 400074 0000000000B9A0102806 30.00 5 ARVIND KUMAR DESAI H NO 2-1-563/2 NALLAKUNTA HYDERABAD 500044 0000000000B9A0106500 30.00 6 BIBISHAB S PATHAN 1005 DENA TOWER OPP ADUJAN PATIYA SURAT 395009 0000000000B9B0007570 144.00 7 BEENA DAVE 703 KRISHNA APT NEXT TO POISAR DEPOT OPP OUR LADY REMEDY SCHOOL S V ROAD, KANDIVILI (W) MUMBAI 400067 0000000000B9B0009430 30.00 8 BABULAL S LADHANI 9 ABDUL REHMAN STREET 3RD FLOOR ROOM NO 62 YUSUF BUILDING MUMBAI 400003 0000000000B9B0100587 30.00 9 BHAGWANDAS Z BAPHNA MAIN ROAD DAHANU DIST THANA W RLY MAHARASHTRA 401601 0000000000B9B0102431 48.00 10 BHARAT MOHANLAL VADALIA MAHADEVIA ROAD MANAVADAR GUJARAT 362630 0000000000B9B0103101 60.00 11 BHARATBHAI R PATEL 45 KRISHNA PARK SOC JASODA NAGAR RD NR GAUR NO KUVO PO GIDC VATVA AHMEDABAD 382445 0000000000B9B0103233 48.00 12 BHARATI PRAKASH HINDUJA 505 A NEEL KANTH 98 MARINE DRIVE P O BOX NO 2397 MUMBAI 400002 0000000000B9B0103411 60.00 13 BHASKAR SUBRAMANY FLAT NO 7 3RD FLOOR 41 SEA LAND CO OP HSG SOCIETY OPP HOTEL PRESIDENT CUFFE PARADE MUMBAI 400005 0000000000B9B0103985 96.00 14 BHASKER CHAMPAKLAL -

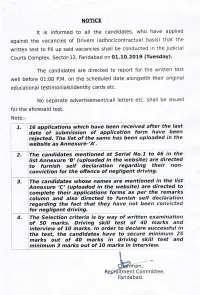

DRIVER LIST and NOTICE for WRITTEN EXAMINATION.Pdf

COMBINE Annexure-A Reject List of applications for the post of Driver August -2019 ( Ad-hoc) as received after due date 20/08/19 Date of Name of Receipt No. Father's / Husband Name Address of the candidate Contact No. Date of Birth Remarks Receipt Candidate Vill-Manesar, P.O Garth Rotmal Application 1 08/21/19 Yogesh Kumar Narender Kumar Teh- Ateli Distt Mohinder Garh 10/29/93 Received after State Haryana 20.08.2019 Khor PO Ateli Mandi Teh Ateli, Application 2 08/21/19 Pankaj Suresh Kumar 9818215697 12/20/93 Received after distt mahendergarh 20.08.2019 Amarjeet S/O Krishan Kumar Application 3 08/21/19 Amarjeet Kirshan Kumar 05/07/92 Received after VPO Bhikewala Teh Narwana 20.08.2019 121, OFFICER Colony Azad Application 4 08/21/19 Bhal Singh Bharat Singh nagar Rajgarh Raod, Near 08/14/96 Received after Godara Petrol Pump Hissar 20.08.2019 Vill Hasan, Teh- Tosham Post- Application 5 08/21/19 Rakesh Dharampal 10/15/97 Received after Rodhan (Bhiwani) 20.08.2019 VPO Jonaicha Khurd, Teh Application 6 08/21/19 Prem Shankar Roshan Lal Neemarana, dist Alwar 12/30/97 Received after (Rajasthan) 20.08.2019 VPO- Bhikhewala Teh Narwana Application 7 08/21/19 Himmat Krishan Kumar 09/05/95 Received after Dist Jind 20.08.2019 vill parsakabas po nagal lakha Application 8 08/21/19 Durgesh Kumar SHIMBHU DAYAL 09/05/95 Received after teh bansur dist alwar 20.08.2019 RZC-68 Nihar Vihar, Nangloi New Application 9 08/26/19 Amarjeet Singh Mohinder Singh 03/17/92 Received after Delhi 20.08.2019 Vill Palwali P.O Kheri Kalan Sec- Application 10 08/26/19 Rohit Sharma -

India—A Land of Contrasts Feels Safe and Comfortable

PAGE EIGHTEEN trip to India is everything it promises to be... and more!!! People who have Abeen there all offer –oddly enough- the same sage advice: “Look beyond the underlying poverty and let yourself be ‘seduced’ by this extraordinary country and its people. It will mark a ‘Before and After’ in your life and most assuredly you will be anxious to return”. This turned out to be my case… and that of all those who accompanied me on this extraordinary trip to India’s Golden Triangle: Delhi, Jaipur and Agra. India is color in the streets, in the saris, in the outdoor marketplaces… It is also spicy smells, fairy tale palaces, noise, crowds, street vendors selling everything imaginable, and overwhelmingly warm and friendly people. To begin with, I would say that it would be hard to find a more hospitable, open and gracious people than the Indians. With a broad and ready smile, they seem to be more than willing to help you, accompany you to where you are going or even pose for a photo. The country itself makes one feel at home and in these difficulties times, the traveler India—A Land of Contrasts feels safe and comfortable. Even the begging children and the persistent street peddlers will respect your “personal” space and TEXT & PHOTOS BY MURIEL FEINER eventually take NO for an answer, after some insistence. limit themselves to passing just on the right, former Viceroy’s Palace and today the Service in the hotels and restaurants is but they are rambling all over the road. Cars President’s Residence, with no less than 350 impeccable and what they may lack in modern approach head-on, but there seem to be few rooms, and also the circular, colonnaded conveniences and state-of-the-art major accidents—thankfully—because it is Parliament House. -

Maharaja Judgement

RSA Nos.2006, 1418 & 2176 of 2018 (O&M) 1 IN THE HIGH COURT OF PUNJAB AND HARYANA AT CHANDIGARH 1. RSA No.2006 of 2018 (O&M) Date of Decision:01.06.2020 Rajkumari Amrit Kaur ......Appellant(s) Vs Maharani Deepinder Kaur and others ....Respondent(s) 2. RSA No.1418 of 2018 (O&M) Maharani Deepinder Kaur and others ......Appellant(s) Vs Rajkumari Amrit Kaur and others ....Respondent(s) 3. RSA No.2176 of 2018 (O&M) Bharat Inder Singh (since deceased) though his LR Kanwar Amarinder Singh Brar ......Appellant(s) Vs Maharwal Khewaji Trust through its Boards of Trustees and others ....Respondent(s) CORAM: HON'BLE MR. JUSTICE RAJ MOHAN SINGH Present: Mr. Manjit Singh Khaira, Sr. Advocate with Mr. Balbir Singh Sewak, Advocate, Mr. Dharminder Singh Randhawa, Advocate Mr. Ripudaman Singh Sidhu, Advocate, and Mr. Gagandeep Singh Mann, Special Attorney Holder for the appellant in RSA No.2006 of 2018 for respondent No.1 in RSA No.1418 of 2018 and for respondent No.6 in RSA No.2176 of 2018. Mr. Ashok Aggarwal, Sr. Advocate with Mr. Mukul Aggarwal, Advocate Mr. N.S. Wahniwal, Advocate for the appellants in RSA No.1418 of 2018 for respondents No.1, 2, 3(1), 3(2), 3(5) & 3(8) in RSA No.2006 of 2018; for respondents No.1(A), 1(B), 1(E), 1(F), 2 and 3 in 1 of 547 ::: Downloaded on - 11-06-2020 14:06:01 ::: RSA Nos.2006, 1418 & 2176 of 2018 (O&M) 2 RSA No.2176 of 2018. Mr. Vivek Bhandari, Advocate for the appellant in RSA No.2176 of 2018 for respondent No.5(i) in RSA No.2006 of 2018 and for respondent No.3(i) in RSA No.1418 of 2018. -

The Kalinga Collection of Nazarana Coins Auction 41

The Kalinga Collection of Nazarana Coins Auction 41 10 Sep. 2015 | The Diplomat Highlight of Auction 39 63 64 133 111 90 96 97 117 78 103 110 112 138 122 125 142 166 169 Auction 41 The Kalinga Collection of Nazarana Coins (with Proof & OMS Coins) Thursday, 10th September 2015 7.00 pm onwards VIEWING Noble Room Monday 7 Sept. 2015 11:00 am - 6:00 pm The Diplomat Hotel Behind Taj Mahal Palace, Tuesday 8 Sept. 2015 11:00 am - 6:00 pm Opp. Starbucks Coffee, Wednesday 9 Sept. 2015 11:00 am - 6:00 pm Apollo Bunder At Rajgor’s SaleRoom Mumbai 400001 605 Majestic Shopping Centre, Near Church, 144 JSS Road, Opera House, Mumbai 400004 Thursday 10 Sept. 2015 3:00 pm - 6:30 pm At the Diplomat Category LOTS Coins of Mughal Empire 1-75 DELIVERY OF LOTS Coins of Independent Kingdoms 76-80 Delivery of Auction Lots will be done from the Princely States of India 81-202 Mumbai Office of the Rajgor’s. European Powers in India 203-236 BUYING AT RAJGOR’S Republic of India 237-245 For an overview of the process, see the Easy to buy at Rajgor’s Foreign Coins 246-248 CONDITIONS OF SALE Front cover: Lot 111 • Back cover: Lot 166 This auction is subject to Important Notices, Conditions of Sale and to Reserves To download the free Android App on your ONLINE CATALOGUE Android Mobile Phone, View catalogue and leave your bids online at point the QR code reader application on your www.Rajgors.com smart phone at the image on left side. -

Orme) Wilberforce (Albert) Raymond Blackburn (Alexander Bell

Copyrights sought (Albert) Basil (Orme) Wilberforce (Albert) Raymond Blackburn (Alexander Bell) Filson Young (Alexander) Forbes Hendry (Alexander) Frederick Whyte (Alfred Hubert) Roy Fedden (Alfred) Alistair Cooke (Alfred) Guy Garrod (Alfred) James Hawkey (Archibald) Berkeley Milne (Archibald) David Stirling (Archibald) Havergal Downes-Shaw (Arthur) Berriedale Keith (Arthur) Beverley Baxter (Arthur) Cecil Tyrrell Beck (Arthur) Clive Morrison-Bell (Arthur) Hugh (Elsdale) Molson (Arthur) Mervyn Stockwood (Arthur) Paul Boissier, Harrow Heraldry Committee & Harrow School (Arthur) Trevor Dawson (Arwyn) Lynn Ungoed-Thomas (Basil Arthur) John Peto (Basil) Kingsley Martin (Basil) Kingsley Martin (Basil) Kingsley Martin & New Statesman (Borlasse Elward) Wyndham Childs (Cecil Frederick) Nevil Macready (Cecil George) Graham Hayman (Charles Edward) Howard Vincent (Charles Henry) Collins Baker (Charles) Alexander Harris (Charles) Cyril Clarke (Charles) Edgar Wood (Charles) Edward Troup (Charles) Frederick (Howard) Gough (Charles) Michael Duff (Charles) Philip Fothergill (Charles) Philip Fothergill, Liberal National Organisation, N-E Warwickshire Liberal Association & Rt Hon Charles Albert McCurdy (Charles) Vernon (Oldfield) Bartlett (Charles) Vernon (Oldfield) Bartlett & World Review of Reviews (Claude) Nigel (Byam) Davies (Claude) Nigel (Byam) Davies (Colin) Mark Patrick (Crwfurd) Wilfrid Griffin Eady (Cyril) Berkeley Ormerod (Cyril) Desmond Keeling (Cyril) George Toogood (Cyril) Kenneth Bird (David) Euan Wallace (Davies) Evan Bedford (Denis Duncan) -

Colonial and Post-Colonial Origins of Agrarian Development: the Case of Two Punjabs

University of Massachusetts Amherst ScholarWorks@UMass Amherst Doctoral Dissertations Dissertations and Theses November 2016 Colonial and Post-Colonial Origins of Agrarian Development: The Case of Two Punjabs Shahram Azhar University of Massachusetts Amherst Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarworks.umass.edu/dissertations_2 Part of the Economic History Commons, Growth and Development Commons, and the Political Economy Commons Recommended Citation Azhar, Shahram, "Colonial and Post-Colonial Origins of Agrarian Development: The Case of Two Punjabs" (2016). Doctoral Dissertations. 726. https://doi.org/10.7275/9043142.0 https://scholarworks.umass.edu/dissertations_2/726 This Open Access Dissertation is brought to you for free and open access by the Dissertations and Theses at ScholarWorks@UMass Amherst. It has been accepted for inclusion in Doctoral Dissertations by an authorized administrator of ScholarWorks@UMass Amherst. For more information, please contact [email protected]. THE COLONIAL AND POST COLONIAL ORIGINS OF AGRARIAN DEVELOPMENT: A CASE OF TWO PUNJABS A Dissertation Presented By SHAHRAM AZHAR Submitted to the Graduate School of the University of Massachusetts Amherst in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY September 2016 Economics © Copyright by Shahram Azhar 2016 All Rights Reserved THE COLONIAL AND POST COLONIAL ORIGINS OF AGRARIAN DEVELOPMENT: A CASE OF TWO PUNJABS A Dissertation Presented by SHAHRAM AZHAR Approved as to style and content by: ___________________________________________ Mwangi wa Gĩthĩnji, Co-Chair ___________________________________________ Deepankar Basu, Co-Chair ___________________________________________ Priyanka Srivastava, Member ___________________________ Michael Ash, Department Chair Economics For Stephen Resnick; a teacher, mentor, and comrade. i ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS This study owes a debt to many people from different parts of the world. -

Provisional List of Not Shortlisted Candidates for the Post of Staff Nurse Under NHM, Assam (Ref: Advt No

Provisional List of Not Shortlisted Candidates for the post of Staff Nurse under NHM, Assam (Ref: Advt No. NHM/Esstt/Adv/115/08-09/Pt-II/ 4621 dated 24th Jun 2016 and vide No. NHM/Esstt/Adv/115/08-09/Pt- II/ 4582 dated 26th Aug 2016) Sl No. Regd. ID Candidate Name Father's Name Address Remarks for Not Shortlisting C/o-KAMINENI HOSPITALS, H.No.-4-1-1227, Vill/Town- Assam Nurses' Midwives' and A KING KOTI, HYDERABAD, P.O.-ABIDS, P.S.-KOTI Health Visitors' Council 1 NHM/SNRS/0658 A THULASI VENKATARAMANACHARI SULTHAN BAZAR, Dist.-RANGA REDDY, State- Registration Number Not TELANGANA, Pin-500001 Provided C/o-ABDUL AZIZ, H.No.-H NO 62 WARD NO 9, Assam Nurses' Midwives' and Vill/Town-GALI NO 1 PURAI ABADI, P.O.-SRI Health Visitors' Council 2 NHM/SNRS/0444 AABID AHMED ABDUL AZIZ GANGANAGAR, P.S.-SRI GANGANAGAR, Dist.-SRI Registration Number Not GANGANAGAR, State-RAJASTHAN, Pin-335001 Provided C/o-KHANDA FALSA MIYON KA CHOWK, H.No.-452, Assam Nurses' Midwives' and Vill/Town-JODHPUR, P.O.-SIWANCHI GATE, P.S.- Health Visitors' Council 3 NHM/SNRS/0144 ABDUL NADEEM ABDUL HABIB KHANDA FALSA, Dist.-Outside State, State-RAJASTHAN, Registration Number Not Pin-342001 Provided Assam Nurses' Midwives' and C/o-SIRMOHAR MEENA, H.No.-, Vill/Town-SOP, P.O.- Health Visitors' Council 4 NHM/SNRS/1703 ABHAYRAJ MEENA SIRMOHAR MEENA SOP, P.S.-NADOTI, Dist.-KAROULI, State-RAJASTHAN, Registration Number Not Pin-322204 Provided Assam Nurses' Midwives' and C/o-ABIDUNNISA, H.No.-90SF, Vill/Town- Health Visitors' Council 5 NHM/SNRS/0960 ABIDUNNISA ABDUL MUNAF KHAIRTABAD, -

Bhiwani, One of the Eleven Districts! of Haryana State, Came Into Existence

Bhiwani , one of the eleven districts! of Haryana State , came into existence on December 22, 1972, and was formally inaugurated on Ja ilUary 14 , 1973. It is mmed after the headquarters . town of Bhiwani , believed to be a corruption of the word Bhani. From Bhani, it changed to Bhiani and then Bhiwani. Tradi tion has it that one Neem , a Jatu Rajput , who belonged to vill age B:twani 2, then in Hansi tahsil of the Hisar (Hissar) di strict , came to settle at Kaunt , a village near the present town of Bhiwani. Thi s was re sen ted by the local Jat inhabitants, and they pl otted his murder. Neem was war ned by a Jat woman , named Bahni, and thus forewarned , had his revenge on th e loc al Jat s. He killed m~st of them at a banquet, the site of which wa s min ed with gun- powder. He m'lrried B:thni and founded a village nam ed after her. At the beginning of the nineteenth century , Bhiwani was an in signifi cant village in the Dadri pargana, under the control of the Nawab of Jhajj ar. It is, how - ever, referred to as a town when the British occupied it in 1810 .3 It gained importance during British rule when in 1817, it was sel ected for the site of a mandi or free market, and Charkhi Dadri, still under the Nawa bs, lost its importance as a seat of commerce. Location and boundaries.- The district of Bhiwani lie s in be twee n latitude 2&0 19' and 290 OS' and longitude 750 28' to 760 28' . -

Birth of a Tragedy Kashmir 1947

A TRAGEDY MIR BIRTH OF A TRAGEDY KASHMIR 1947 Alastair Lamb Roxford Books Hertingfordbury 1994 O Alastair Lamb, 1994 The right of Alastair Lamb to be identified as the Author of the Work has been asserted by him in accordance with the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act 1988. First published in 1994 by Roxford Books, Hertingfordbury, Hertfordshire, U.K. All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording or otherwise, without the prior permission in writing of the publishers. ISBN 0 907129 07 2 Printed in England by Redwood Books, Trowbridge, Wiltshire Typeset by Create Publishing Services Ltd, Bath, Avon Contents Acknowledgements vii I Paramountcy and Partition, March to August 1947 1 1. Introductory 1 2. Paramountcy 4 3. Partition: its origins 13 4. Partition: the Radcliffe Commission 24 5. Jammu & Kashmir and the lapse of Paramountcy 42 I1 The Poonch Revolt, origins to 24 October 1947 54 I11 The Accession Crisis, 24-27 October 1947 81 IV The War in Kashmir, October to December 1947 104 V To the United Nations, October 1947 to 1 January 1948 1 26 VI The Birth of a Tragedy 165 Maps 1. The State of Jammu & Kashmir in relation to its neighbours. ix 2. The State ofJammu & Kashmir. x 3. Stages in the creation of the State ofJammu and Kashmir. xi 4. The Vale of Kashmir. xii ... 5. Partition boundaries in the Punjab, 1947. xlll Acknowledgements ince the publication of my Karhmir. A Disputed Legmy 1846-1990 in S199 1, I have been able to carry out further research into the minutiae of those events of 1947 which resulted in the end ofthe British Indian Empire, the Partition of the Punjab and Bengal and the creation of Pakistan, and the opening stages of the Kashmir dispute the consequences of which are with us still. -

2012 Vol.1 Part I, II, III & IV Contents, Index, Reference and Title

(ii) (i) (iii) (iv) (v) (vi) (vii) (viii) (x) (ix) (xi) (xii) (xiv) (xiii) (xvi) (xv) (xviii) (xvii) (xx) CONTENTS Balwinder Singh and Ors.; State of Punjab v. .... 45 A.V.M. Sales Corporation v. M/s. Anuradha Bavo @ Manubhai Ambalal Thakore v. State Chemicals Pvt. Ltd. .... 318 of Gujarat .... 822 Absar Alam @ Afsar Alam v. State of Bihar .... 890 Bhanot (V.D.) v. Savita Bhanot .... 867 Alister Anthony Pareira v. State of Maharashtra .... 145 Bhartiya Khadya Nigam Karmchari Sangh & Anr.; Food Corporation of India & Ors. v..... 230 Ambrish Tandon & Anr.; State of U.P. & Ors. v. .... 422 Bheru Singh & Ors.; State of Madhya Pradesh Amit v. State of Uttar Pradesh .... 1009 & Anr. v. .... 535 Ansaldo Caldaie Boilers India P. Ltd. & Anr.; Bishnu Deo Bhandari; Mangani Lal Mandal v. .... 527 NTPC Limited v. .... 966 Brundaban Gouda & Anr.; Joshna Gouda v. .... 464 Anuradha Chemicals Pvt. Ltd. (M/s.); A.V.M. Sales Corporation v. .... 318 Burdwan Central Cooperative Bank Ltd. & Anr. v. Asim Chatterjee & Ors. .... 390 Archaeological Survey of India v. Narender Anand and others .... 260 C.B.I., Delhi & Anr.; Dr. Mrs. Nupur Talwar v. .... 31 Arup Das & Ors. v. State of Assam & Ors. .... 445 Chandra Narain Tripathi; Kapil Muni Karwariya v. .... 956 Asim Chatterjee & Ors.; Burdwan Central Cooperative Bank Ltd. & Anr. v. .... 390 Commissioner of Central Excise, U.P.; (M/s.) Flex Engineering Limited v. .... 209 Assam Urban Water Supply & Sew. Board v. Subash Projects & Marketing Ltd. .... 403 Commnr. of Central Excise, Faridabad v. M/s Food & Health Care Specialities & Anr. .. 908 Assistant Commissioner of Commercial Taxes & Anr.; Hotel Ashoka (Indian Tour.