Minnesota Constitutional Amendments History and Legal Principles

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Education Clauses in State Constitutions Across the United States∗

Education Clauses in State Constitutions Across the United States∗ Scott Dallman Anusha Nath January 8, 2020 Executive Summary This article documents the variation in strength of education clauses in state constitu- tions across the United States. The U.S. Constitution is silent on the subject of education, but every state constitution includes language that mandates the establishment of a public education system. Some state constitutions include clauses that only stipulate that the state provide public education, while other states have taken more significant measures to ensure the provision of a high-quality public education system. Florida’s constitutional education clause is currently the strongest in the country – it recognizes education as a fundamen- tal value, requires the state to provide high-quality education, and makes the provision of education a paramount duty of the state. Minnesota can learn from the experience of other states. Most states have amended the education clause of their state constitutions over time to reflect the changing preferences of their citizens. Between 1990 and 2018, there were 312 proposed amendments on ballots across the country, and 193 passed. These amendments spanned various issues. Policymakers and voters in each state adopted the changes they deemed necessary for their education system. Minnesota has not amended its constitutional education clause since it was first established in 1857. Constitutional language matters. We use Florida and Louisiana as case studies to illus- trate that constitutional amendments can be drivers of change. Institutional changes to the education system that citizens of Florida and Louisiana helped create ultimately led to im- proved outcomes for their children. -

Veto Power of the Governor of Minnesota

Veto Power of the Governor of Minnesota Peter S. Wattson Senate Counsel State of Minnesota September 12, 1995 Contents Table of Authorities ........................................................... iii Minnesota Constitution .................................................. iii Minnesota Statutes and Laws .............................................. iii Minnesota Cases ....................................................... iii Cases from Other States .................................................. iii Other Authorities ....................................................... iv I. Veto of a Bill ...........................................................1 A. The Minnesota Constitution ........................................1 B. Constitutional Issues ..............................................1 1. How Much Time Does the Governor Have to Make Up His Mind? ..1 2. How are the Three Days Computed? ...........................2 3. Where and To Whom Must the Return be Made? ................2 4. Must the Return be Made When the House of Origin is in Actual Session? ...................................................2 5. Does an Adjournment at the End of the First Year of a Biennial Session Prevent the Return of a Vetoed Bill? ....................3 C. Seventy-seventh Minnesota State Senate v. Carlson ......................3 II. Item Vetoes ............................................................5 A. The Minnesota Constitution ........................................5 B. Constitutional Issues ..............................................6 -

Inside the Minnesota Senate

Inside the Minnesota Senate Frequently Asked Questions This booklet was prepared by the staff of the Secretary of the Senate as a response to the many questions from Senate staff and from the public regarding internal operations of the Minnesota Senate. We hope that it will be a valuable source of information for those who wish to have a better understanding of how the laws of Minnesota are made. Your suggestions for making this booklet more useful and complete are welcome. Cal R. Ludeman Secretary of the Senate Updated February 2019 This document can be made available in alternative formats. To make a request, please call (voice) 651-296-0504 or toll free 1-888-234-1112. 1 1. What is the state Legislature and what is its purpose? There are three branches of state government: the executive, the judicial and the legislative. In Minnesota, the legislative branch consists of two bodies with members elected by the citizens of the state. These two bodies are called the Senate and the House of Representatives. Upon election, each Senator and Representative must take an oath to support the Constitution of the United States, the Constitution of this state, and to discharge faithfully the duties of the office to the best of the member’s judgment and ability. These duties include the consideration and passage of laws that affect all of us. Among other things, laws passed by the Legislature provide for education, protect our individual freedoms, regulate commerce, provide for the welfare of those in need, establish and maintain our system of highways, and attempt to create a system of taxation that is fair and equitable. -

Constitution of Minnesota William Anderson

University of Minnesota Law School Scholarship Repository Minnesota Law Review 1921 Constitution of Minnesota William Anderson Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarship.law.umn.edu/mlr Part of the Law Commons Recommended Citation Anderson, William, "Constitution of Minnesota" (1921). Minnesota Law Review. 2509. https://scholarship.law.umn.edu/mlr/2509 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the University of Minnesota Law School. It has been accepted for inclusion in Minnesota Law Review collection by an authorized administrator of the Scholarship Repository. For more information, please contact [email protected]. MINNESOTA LAW REVIEW VOL. V MAY, 1921 No. 6 THE CONSTITUTION OF MINNESOTA' By WILLIAM ANDERSON* 1. THE MOVEMENT FOR STATEHOOD THE organized territory of Minnesota existed from 1849 to 1858. Included within its areas was not only the present state of Minnesota but also those portions of the present states of North and South Dakota which lie east of the Missouri and White Earth rivers. In this extensive region, double the area of the present state, there were at the beginning of the territorial period a scant five thousand people of the white race. The population increased slowly at the outset. The lands west of the Mississippi were not opened to settlement until after the conclusion of the Indian treaties of 1851 and 1852. In 1854, with the opening of the first railroad from Chicago to the Mississippi, the inrush began, thousands of settlers coming each year from New Eng- land, New York, and the states north of the Ohio. By 1857 there were 150,000 people in the territory. -

AVAILABLE from Andbill of Rights, and the Minnesota Constitution

DOCUMENT RESUME 1-,) 374 067 SO 024 501 AUTHOR Bloom, Jennifer, Ed. TITLE Rights of the Accused; Criminal Amendments in the Bill of Rights. A Compilation of Lessons by Minnesota Teachers. INSTITUTION Hamline Univ., St. Paul, MN. School of Law. SPONS AGENCY . Commission on the Bicentennial of the United States Constitution, Washington, DC. PUB DATE 91 CONTRACT 9I-CB-CX-0078 NOTE 414p.; For related items, see SO 024 499 and SO 024 502-503. AVAILABLE FROMMinnesota Center for Community Legal Education, Hamline University School of Law, 1536 Hewitt Avenue, St. Paul, MN 55104. PUB TYPE Guides,- Classroom Use Instructional Materials (For Learner) (051) Guides Classroom Use Teaching Guides (For Teacher) (052) EDRS PRICE MF01/PC17 Plus Postage. DESCRIPTORS Citizenship Education; *Civil Liberties; *Constitutional Law; *Criminal Law; *Due Process; Equal Protection; Intermediate Grades; JuniorHigh Schools; *Law Related Education; Resource Materials; Resource Units IDENTIFIERS *Bill of Rights; Hamline University MN; Minnesota ABSTRACT The 36 lessons collected in this publication are designed to introduce studenti to the rights of the accusedand provide a scholarly study of these rights, exploringhistorical development as well as current application. Lessons areprovided for all grade levels. The topics covered include theBill of Rights, criminal rights amendments, juvenile law, and legalethics. An appendix contains the U.S. Bill of Rights, asimplified Constitution andBill of Rights, and the Minnesota Constitution.(RJC) *********************************************************************** Reproductions supplied by EDRS are the best that can bemade from the original document. *********************************************************************** U.S. DEPARTMENT Of EDUCATION °MCatEducst*osl Research and Improvernnt EDUC>TIONAL RESOURCES INFORMATION CENTER (ERIC) his document has hen (roducts, m escivscl from the proson or °roams:ion originating it. -

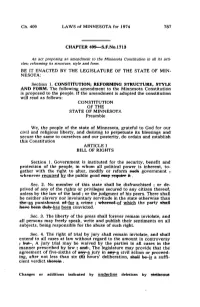

CHAPTER 409—S.F.No.1713 BE IT ENACTED by the LEGISLATURE of the STATE of MIN- NESOTA: Section 1. CONSTITUTION; REFORMING STRUC

Ch. 409 LAWS of MINNESOTA for 1974 787 CHAPTER 409—S.F.No.1713 An act proposing an amendment to the Minnesota Constitution in all its arti- cles; reforming its structure, style and form. BE IT ENACTED BY THE LEGISLATURE OF THE STATE OF MIN- NESOTA: Section 1. CONSTITUTION; REFORMING STRUCTURE, STYLE AND FORM. The following amendment to the Minnesota Constitution is proposed to the people. If the amendment is adopted the constitution will read as follows: CONSTITUTION OF THE STATE OF MINNESOTA Preamble We, the people of the state of Minnesota, grateful to God for our civil and religious liberty, and desiring to' perpetuate its blessings and secure the same to ourselves and our posterity, do ordain and establish this Constitution ARTICLE I BILL OF RIGHTS Section 1. Government is instituted for the security, benefit and protection of the people, in whom all political power is inherent, to- gether with the right to alter, modify or reform sttefc government 7 whenever required by the public good may require it. Sec. 2. No member of this state shall be disfranchised ; or de- prived of any of the rights or privileges secured to any citizen thereof, unless by the law of the land 7 or the judgment of his peers. There shall be neither slavery nor involuntary servitude in the state otherwise than the as punishment ef-for a crime 7 whereof of which the party shaH have bee» d«ty-has been convicted. Sec. 3. The liberty of the press shall forever remain inviolate, and all persons may freely speak, write and publish their sentiments on all subjects, being responsible for the abuse of such right. -

Information on the Process for Appointing an Auditor-Treasurer

County Administrator Julia Lines COMMISSIONERS Lindsey Giese Human Resources Director/ 1st District 2nd District 3rd District Deputy County Administrator Dave Oslund Terry Turnquist Greg Anderson Sharon Katka Government Center Human Resources Generalist 555 18th Avenue SW 4th District 5th District Cambridge, MN 55008 Mike Warring Susan Morris Halee Turner 763-689-3859 - Phone Administrative Assistant II 763-689-8226 - Fax Mission Working Together to Deliver Quality Services that are Valued by the Community, Today and Tomorrow APPOINTMENT OF ISANTI COUNTY AUDITOR-TREASURER INTRODUCTORY BACKGROUND STATEMENT The Isanti County strategic plan priorities include increasing efficiency and effectiveness in values that provide quality service and continuous improvement to the citizens of Isanti County. As part of that ongoing process in 2020 Isanti County retained the services of DDA Human Resources, Inc., a David Drown Associates Company to provide Isanti County with an organizational review of current County Department operations. The study was conducted in order to identify areas where customer service could be improved, and greater efficiencies could be realized. At the time the study was conducted in 2020 DDA Human Resources, Inc. noted the Isanti County structure included four departments comprised of elected official leaders and 13 other departments, each having its own respective leader. Part of the resulting study recommendations was the creation of a new division structure for which the Isanti County Board of Commissioners supported as did the majority of lead staff and their respective staff. As a result the Public Health and Family Services Departments have been combined as the Health and Human Services Division. The Technology, Geographic Information Systems, Facilities and Maintenance Departments are now combined into the Central Services Division. -

Permissibility of Omnibus Bills Under the Minnesota Constitution's Single

Senate Counsel, Research, and Fiscal Analysis State of Minnesota Permissibility of Omnibus Bills under the Minnesota Constitution’s Single Subject Clause Peter S. Wattson Senate Counsel Revised February 2018 Ben Stanley Senate Counsel This memorandum examines the application of the Minnesota constitution’s single subject clause to the legislative practice of enacting omnibus bills. An omnibus bill is a bill that funds multiple state agencies and makes related substantive law changes in a single large bill. It thus combines numerous measures that are related but could be enacted separately.1 The single subject clause is located in article 4, sec. 17, of the Minnesota Constitution and provides that “[n]o law shall embrace more than one subject, which shall be expressed in its title.” The clause thus creates two requirements: first, that a bill embrace only one subject and second, that the subject be expressed in the bill’s title.2 While it is possible for the inclusion of a particular provision in an omnibus bill to violate the single subject clause, this memorandum concludes that omnibus bills are generally consistent with constitutional limitations when carefully constructed. Purpose of The Single Subject Clause The primary purpose of the single subject clause is to prevent logrolling, that is, combining into one bill several distinct provisions, each of which is supported only by a minority of members, but which, when voted for as a package, will have majority support. As the Minnesota Supreme Court said in 1875: The well-known object -

Report of the Legislative Salary Council 3-23-2021

This document is made available electronically by the Minnesota Legislative Reference Library as part of an ongoing digital archiving project. http://www.leg.state.mn.us/lrl/lrl.asp Legislative Salary Council 72 State Office Building St. Paul, MN 55155-1201 Phone: (651) 296-9002 Fax: (651) 297-3697 TDD (651) 296-9896 March 23, 2021 Representative Melissa Hortman Senator Jeremy Miller Speaker of the House President of the Senate Representative Ryan Winkler Senator Paul Gazelka House Majority Leader Senate Majority Leader Representative Kurt Daudt Senator Susan Kent House Minority Leader Senate Minority Leader Representative Michael Nelson Senator Mary Kiffmeyer Chair, State Government Finance Division Chair, State Government Finance and Policy and Elections Committee Representative Rena Moran Senator Julie Rosen Chair, Ways and Means Committee Chair, Finance Committee Governor Tim Walz Chief Justice Lorie S. Gildea Dear Governor Walz, Chief Justice Gildea, Representatives and Senators, I am writing to you on behalf of the Legislative Salary Council. The Minnesota Constitution, Article IV, section 9, and Minnesota Statutes 2020, section 15A.0825 establishes the Legislative Salary Council (Council) whose responsibility is to prescribe the salaries of Minnesota state legislators by March 31st of each odd-numbered year. The Council has held three meetings and considered all forms of legislative compensation, the budget forecast, and an extensive amount of other data and analysis, as reflected in the attached report. Based on our consideration of these materials and our extended discussion, the Legislative Salary Council prescribes that salaries of Minnesota senators and representatives be set at $48,250, effective July 1, 2021. Our report provides detail regarding our process, the data and reports that we considered, and the testimony that we received in the course of our work. -

Federalism, Convergence, and Divergence in Constitutional Property

Pittsburgh University School of Law Scholarship@PITT LAW Articles Faculty Publications 2018 Federalism, Convergence, and Divergence in Constitutional Property Gerald S. Dickinson Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarship.law.pitt.edu/fac_articles Part of the Administrative Law Commons, Constitutional Law Commons, Courts Commons, Housing Law Commons, Land Use Law Commons, Law and Society Commons, Property Law and Real Estate Commons, and the Supreme Court of the United States Commons Recommended Citation Gerald S. Dickinson, Federalism, Convergence, and Divergence in Constitutional Property, 73 University of Miami Law Review 139 (2018). Available at: https://scholarship.law.pitt.edu/fac_articles/78 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Faculty Publications at Scholarship@PITT LAW. It has been accepted for inclusion in Articles by an authorized administrator of Scholarship@PITT LAW. For more information, please contact [email protected], [email protected]. Federalism, Convergence, and Divergence in Constitutional Property GERALD S. DICKINSON* Federal law exerts a gravitationalforce on state actors, resulting in widespread conformity to federal law and doc- trine at the state level. This has been well recognized in the literature,but scholars have paid little attention to this phe- nomenon in the context of constitutionalproperty. Tradition- ally, state takings jurisprudence-in both eminent domain and regulatory takings-hasstrongly gravitatedtowards the Supreme Court's takings doctrine. This long history offed- eral-state convergence, however, was disrupted by the Court's controversialpublic use decision in Kelo v. City of New London. In the wake ofKelo, states resisted the Court's validation of the economic development justification for public use, instead choosing to impose expansive private property protections beyond the federal minima. -

The Minnesota Judiciary: a Guide for Legislators

The Minnesota Judiciary: A Guide for Legislators About this Publication This publication describes the structure, functions, personnel, and finances of the judicial branch of state government in Minnesota. By Ben Johnson, Legislative Analyst September 2019 Contents Executive Summary ............................................................................................................. 1 Judicial Branch Overview .................................................................................................... 2 Role of the Judiciary ..................................................................................................... 2 State Judicial Districts Map .......................................................................................... 4 Relationship between the Legislature and Judiciary .................................................... 6 State Court Jurisdiction and Appeals Routes ............................................................... 7 Special Statutory Courts Not in the Judicial Branch ..................................................... 8 Relationship between State and Federal Court Systems ............................................. 9 Court Personnel and Operations ...................................................................................... 10 Judges ......................................................................................................................... 10 Para-Judicial Officers ................................................................................................. -

A History of the Constitution of Minnesota (1921)

This is a reproduction of a library book that was digitized by Google as part of an ongoing effort to preserve the information in books and make it universally accessible. http://books.google.com HARVARD COLLEGE LIBRARY TRANSFERRED FROM THE BUREAU FOR RESEARCH IN MUNICIPAL GOVERNMENT RESEARCH PUBLICATIONS OF THE UNIVERSITY OF MINNESOTA These publications contain the results of research work from various depart ments of the University and are offered for exchange with universities, scientific societies, and other institutions. Papers will be published as separate monographs numbered in several series. There is no stated interval of publication. Application for any of these publications should be made to the University Librarian. BIBLIOGRAPHICAL SERIES 1. Jambs Thayer Gebould, Sources of English History of the Seventeenth Century, 1603-1689, in the University of Minnesota Library, with a Selection of Secondary Material. 1921. $4.00. STUDIES IN THE SOCIAL SCIENCES 1. Thompson and Warber, Social and Economic Survey of a Rural Township in Southern Minnesota. 1913. $0.50. 2. Matthias Nordbbrg Orfield, Federal Land Grants to the States, with Special Reference to Minnesota. 1915. $1.00. 3. Edward Van Dyke Robinson, Early Economic Conditions and the Develop ment of Agriculture in Minnesota. 1915. $1.50. 4. L. D. H. Weld and Others, Studies in the Marketing of Farm Products. 1915. $0.50. 5. Ben Palmer, Swamp Land Drainage, with Special Reference to Minnesota. 1915. $0.50. 6. Albert Ernest Jenks, Indian-White Amalgamation: An Anthropometric Study. 1916. $0.50. 7. C. D. Allin, A History of the Tariff Relations of the Australian Colonies.