Discipline, Discours

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

PEAES Guide: Cliveden

PEAES Guide: Cliveden http://www.librarycompany.org/Economics/PEAESguide/cliveden.htm Keyword Search Entire Guide View Resources by Institution Search Guide Institutions Surveyed - Select One Cliveden Contact information: Researchers are advised to call ahead for an appointment to read manuscript materials: (215) 848-1777 or [email protected]. Overview: Cliveden is an historic house museum on 6 acres of landscaped grounds in the Germantown neighborhood of Philadelphia's Historic Northwest. The property was the scene of the Battle of Germantown in October, 1777, and home to the descendants of the original owner until 1972. Includes original furnishings and decorative arts, including superlative examples of colonial Philadelphia craftsmanship by James Reynolds, Jonathan Gostelowe and Thomas Affleck. Cliveden is located on the northeast corner of Germantown Avenue and Johnson Streets, north of downtown Philadelphia in Germantown. From the PA Turnpike (1-276) take exit 333( formerly Exit 25, Norristown) and follow Germantown Pike east about seven miles to Cliveden on the left. Enter from Cliveden Street. From the Schuylkill Expressway (1-76) take exit 340 (formerly Exit 32) to the Lincoln Drive. Turn right onto Johnson Street (third light) then left onto Germantown Avenue (fourth light). Take the first right onto Cliveden St. Entrance gate is on the right at the end of the first block. We urge you to take a tour of the house while you are there, and walk Germantown Avenue to see other late-18 th century houses and businesses. Resources at Cliveden available to scholars upon request: Chew family papers (Cliveden) 21 linear feet, finding aid available. -

Cliveden Bibliography

Cliveden Resources and Bibliography Updated 11/15/02 Introduction The following list has three parts: Part I lists archival and other collections—many of them very large—that tell a part of the Cliveden story. Part II lists the various research tools and resources available at Cliveden. These include reports from numerous research projects undertaken since the site was given to the National Trust in 1972, many of them in computer-readable form. Part III is an extensive bibliography of works about Cliveden or the people who lived there. Because these publications are numerous, they have been divided into categories such as “Architecture” or “Tour Guides.” There are undoubtedly many omissions, but additional items will be added as they come to our attention, in the hope that the list will one day be comprehensive. Part I: Collections Primary source materials at Cliveden Chew family library Legal library contains approximately 200 items dating from 1627 to the late eighteenth century. General library includes later legal titles plus 800 general interest titles from the eighteenth, nineteenth and early twentieth centuries. Alphabetical author listing and shelf list available. Chew family papers 40+ linear feet of standard legal document boxes plus four large map cases of containing oversize materials. Item level finding aid available. Consists primarily of Chew family papers and photographs found in house after the bulk of collection was transferred to the Historical Society of Pennsylvania in 1972. Object collections Approximately 3,000 objects dating from the mid-eighteenth century to 1972. Bulk of collection consists of furniture and other decorative arts materials, textiles, paintings and graphics. -

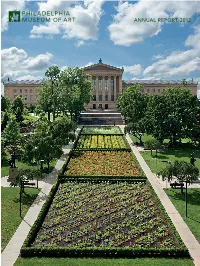

Annual Report 2012

BOARD OF TRUSTEES 4 LETTER FROM THE CHAIR 6 A YEAR AT THE MUSEUM 8 Collecting 10 Exhibiting 20 Teaching and Learning 30 Connecting and Collaborating 38 Building 44 Conserving 50 Supporting 54 Staffing and Volunteering 62 CALENDAR OF EXHIBITIONS AND EVENTS 68 FINANCIAL StATEMENTS 72 COMMIttEES OF THE BOARD OF TRUSTEES 78 SUPPORT GROUPS 80 VOLUNTEERS 83 MUSEUM StAFF 86 A REPORT LIKE THIS IS, IN ESSENCE, A SNAPSHOT. Like a snapshot it captures a moment in time, one that tells a compelling story that is rich in detail and resonates with meaning about the subject it represents. With this analogy in mind, we hope that as you read this account of our operations during fiscal year 2012 you will not only appreciate all that has been accomplished at the Philadelphia Museum of Art, but also see how this work has served to fulfill the mission of this institution through the continued development and care of our collection, the presentation of a broad range of exhibitions and programs, and the strengthening of our relationship to the com- munity through education and outreach. In this regard, continuity is vitally important. In other words, what the Museum was founded to do in 1876 is as essential today as it was then. Fostering the understanding and appreciation of the work of great artists and nurturing the spirit of creativity in all of us are enduring values without which we, individually and collectively, would be greatly diminished. If continuity—the responsibility for sustaining the things that we value most—is impor- tant, then so, too, is a commitment to change. -

Information to Users

INFORMATION TO USERS This manuscript has been reproduced from the microfilm master. UMI films the text directly from the original or copy submitted. Thus, some thesis and dissertation copies are in typewriter face, while others may be from any type of computer printer. The quality of this reproduction is dependent upon the quality of the copy subm itted. Broken or indistinct print, colored or poor quality illustrations and photographs, print bleedthrough, substandard margins, and improper alignment can adversely affect reproduction. In the unlikely event that the author did not send UMI a complete manuscript and there are missing pages, these will be noted. Also, if unauthorized copyright material had to be removed, a note will indicate the deletion. Oversize materials (e.g., maps, drawings, charts) are reproduced by sectioning the original, beginning at the upper left-hand comer and continuing from left to right in equal sections with small overlaps. Photographs included in the original manuscript have been reproduced xerographically in this copy. Higher quality 6* x 9" black and white photographic prints are available for any photographs or illustrations appearing in this copy for an additional charge. Contact UMI directly to order. ProQuest Information and Learning 300 North Zeeb Road, Ann Arbor, Ml 48106-1346 USA 800-521-0600 Reproduced with permission of the copyright owner. Further reproduction prohibited without permission. Reproduced with permission of the copyright owner. Further reproduction prohibited without permission. NOTE TO USERS This reproduction is the best copy available. UMI Reproduced with permission of the copyright owner. Further reproduction prohibited without permission. Reproduced with permission of the copyright owner. -

Book Reviews and Book Notes

BOOK REVIEWS AND BOOK NOTES EDITED BY NORMAN B. WILKINSON C,;0lnial Grandeur in Philadelphia, The House and Furniture of General John Cadwalader. By Nicholas B. Wainwright. (Philadelphia: His- torical Society of Pennsylvania, 1964. Pp. 169. $10.00.) Colonial Grandeur in Philadelphiais an elegant micro-organism importantly anchored within the broad spectrum of American cultural history. A book of admittedly limited scope, the volume, however, accomplishes its aim oia nificently. Meticulously, with the care and attention to minute detail which usually characterize the archaeologist's attempt to reconstruct the story of life in a Pompeii or a Tikal, Mr. Wainwright has rescued from the historical penumbras the image of one of America's most sophisticated Georgian mansions-the home of General John Cadwalader which stood on Second Street near Spruce. Built by Samuel Rhoads in 1760, the great house was snlbsequently purchased by Cadwalader who, between 1769 and 1771, had it remodeled into one of Philadelphia's most sumptuous dwellings. The build- ing suffered a typically American fate when it was torn down by Stephen Girard early in the nineteenth century to provide land for redevelopment. Through the study of bills and inventories, and by making comparisons with existing structures and interiors, the author presents a vivid under- standing of the appearance of the house which, including furnishings, cost some £9,000. Among the great colonial craftsmen of Philadelphia who wvorked on the mansion and its contents were Philip Syng, Thomas Affleck, and William Savery. A number of the bills which artisans submitted for their services are reproduced, thereby enhancing the book's value as a useful reference for determining contemporary prices. -

John Cadwalader (General) - Wikipedia

John Cadwalader (general) - Wikipedia https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/John_Cadwalader_(general) John Cadwalader (January 10, 1742 – February 10, 1786) was a John Cadwalader commander of Pennsylvania troops during the American Revolutionary War and served under George Washington. He was with Washington during the Delaware River crossing and the Battle of Trenton and at Valley Forge. Early life Revolutionary War Later life Furniture Family tree Notes Philadelphia Museum of Art References John and Elizabeth Lloyd External links Cadwalader and their Daughter Anne (1772) by Charles Willson Peale. Born January 10, 1742 John Cadwalader was born in Trenton, New Jersey of Quaker parentage, Trenton, New Jersey the eldest son of Thomas Cadwalader (1707–1779) and Hannah Lambert, Died February 10, 1786 his wife.[1][2] In 1750, the Cadwalader family removed to Philadelphia (aged 44) where John and Lambert Cadwalader, his brother, were merchants. Kent County, Maryland On September 25, 1768, John Cadwalader married Elizabeth Lloyd Occupation Merchant (1742–1776), the daughter of Edward Lloyd, of Talbot County, Maryland. Her brother, Edward Lloyd IV, was a delegate to the Continental Congress Spouse(s) Elizabeth Lloyd for Maryland.[3] Their daughter, Maria Cadwalader (1776–1811), married Williamina Bond Samuel Ringgold, who became a congressman representing Maryland. Two Children Anne, b: 1771 of their sons, Samuel Ringgold and Cadwalader Ringgold, had Elizabeth, b: 1774 distinguished military careers. Maria, b: 1776 Thomas, b: 1779 Frances, b: 1781 John, -

The First Generation Furniture of Drayton Hall

Clemson University TigerPrints All Theses Theses 5-2015 "Nine Mahogany Table…Two Marble Slabbs and Stands…and a Cow": The irsF t Generation Furniture of Drayton Hall Shannon Marie Devlin Clemson University Follow this and additional works at: https://tigerprints.clemson.edu/all_theses Part of the Historic Preservation and Conservation Commons Recommended Citation Devlin, Shannon Marie, ""Nine Mahogany Table…Two Marble Slabbs and Stands…and a Cow": The irF st Generation Furniture of Drayton Hall" (2015). All Theses. 2137. https://tigerprints.clemson.edu/all_theses/2137 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Theses at TigerPrints. It has been accepted for inclusion in All Theses by an authorized administrator of TigerPrints. For more information, please contact [email protected]. “NINE MAHOGANY TABLES...TWO MARBLE SLABBS AND STANDS... AND A COW”: THE FIRST GENERATION FURNITURE OF DRAYTON HALL A Thesis Presented to the Graduate School of Clemson University In Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree Master of Science Historic Preservation by Shannon Marie Devlin May 2015 Accepted by: Carter L. Hudgins, Ph.D., Committee Chair Ralph C. Muldrow Elizabeth Garrett Ryan Carter C. Hudgins, Ph.D. Sarah Stroud Clarke ABSTRACT When the National Trust for Historic Preservation purchased Drayton Hall in 1974, they made a groundbreaking decision. The Trust took a conservation approach to the house, preserving Drayton Hall as found and presenting it to the public unfurnished. The decision proved to have significant ramifications and as a direct result, interpreting the material culture at the site slid to the side. Drayton Hall has over a million objects in its collections ranging from archaeo- logical sherds to pieces of furniture, yet the collections play little to no role in site inter- pretation to the public. -

Book Reviews

BOOK REVIEWS Colonial Grandeur in Philadelphia. The House and Furniture of General John Cadwalader. By NICHOLAS B. WAINWRIGHT. Foreword by HENRY FRANCIS DUPONT. (Philadelphia: The Historical Society of Pennsyl- vania, 1964. xiv, 169 p. Illustrations, appendix, index. $10.00.) This welcome book gives us for the first time, step by step, a documented account of how the interior architecture and furnishing of a great eighteenth- century Philadelphia mansion was accomplished. The first half of the book is divided into three sections: the building of the John Cadwalader house, its furnishings, and its history. Like Samuel Powel, John Dickinson and several other prominent Philadelphians of this period, Cadwalader did not build his house but bought it already built and then embarked on complete renovation. John Cadwalader commissioned Thomas Nevell, prominent member of the Carpenters' Company, as master carpenter in charge of the operation. Nevell's plan was to strip the house of all the plain Quaker woodwork originally installed by its prolific builder, Samuel Rhoads, and to replace it with elaborately paneled, carved and fretted mouldings suitable to the tastes of the new owner. NevelPs designs were doubtless inspired from Abraham Swan's The British Architect, as he was a subscription agent for the Philadelphia edition of this work. They were probably not slavish copies for, with the exception of a few details, there are no illustrations in Swan that match exactly the description of John Cadwalader's house. A new service wing was to be added, as well as a stable and carriage house, but the basic plan of the main house was to stay unchanged. -

Quaker Artists

Quaker Artists Did you know that James Michener and Anne Tyler are Quakers? That Joan Baez, Ben Kingsley and F. Murray Abraham attend Friends Meeting? That Bonnie Raitt and James Dean were raised Friends? That a Quaker Tapestry and Quaker stained glass exist? That Chinese Friends art exists? That Walt Whitman was influenced by Friends? That Margaret Fell wrote poetry? The book Quaker Artists contains the stories of the above artists and more: 94 reviews in all, a history of Friends, a history of Quaker art, study questions, 27 illustrations, 30 reproductions of the artists' works and a bibliography. The period covered is 1659 to 1992. Poets, painters, dancers, musicians, films and 14 other categories are included. Quaker Artists is an entertaining and celebratory read in itself but it has other uses, too: as a source for study groups, a reference for libraries and a curriculum for First Day Schools. Gary Sandman, a member of Fifteenth Street Meeting in New York City, has published Quaker Artists, his first book, in a numbered and signed edition. Cost is $16 (postage included). Check or money order should be made out to Gary Sandman, 25-26 18th St., Apt. 1F, Astoria NY 11102, 718-728-7372. Here is a series of Gary’s research into the variety and history of Quaker involvement in the arts. Fine arts Approved expressions Unpopular pursuits • James Turrell, artist of • Plain dress • Friends and music light • Silhouettes • Quaker cabinetmakers • Samuel Lucas, painter • “Popeye the Quaker • The Richardson Man” silversmiths Friends in Literature • Henry Wadsworth Longfellow, “John Endicott” • Anna Sewell, Black Beauty • Sword of Peace • The Intolerants • Rex Stout, the Nero Wolfe mysteries • Sarah M. -

Stellar Collection of Early American Furniture, Dutch and American Paintings, and Works on Paper Acquired by George M

Office of Press and Public Information Fourth Street and Constitution Av enue NW Washington, DC Phone: 202-842-6353 Fax: 202-789-3044 www.nga.gov/press Release Date: November 12, 2010 Stellar Collection of Early American Furniture, Dutch and American Paintings, and Works on Paper Acquired by George M. and Linda H. Kaufman of Norfolk, Va, to be Given to the National Gallery of Art, Washington Philadelphia, Pennsy lv ania Chippendale Desk and Bookcase Circa 1765 Attributed to Thomas Af f leck George M.* and Linda H. Kauf man Washington, DC—One of the largest and most refined collections of early American furniture in private hands, as well as major Dutch paintings, American paintings, and works on paper, including some 40 floral watercolors by Redouté, acquired with great connoisseurship together over four decades by George M. and Linda H. Kaufman, have been promised to the National Gallery of Art, Washington. A temporary exhibition highlighting the early American furniture will take place at the Gallery in two years. "While building their exceptional collection of art and antiques, Linda and George Kaufman have been leaders, as well as generous lenders and donors, in the art world, and especially at the National Gallery of Art," said Earl A. Powell III, director, National Gallery of Art. "One of America's earliest art forms was furniture influenced by European traditions, and this is an opportunity for the Gallery to complement not only our European decorative arts donated by the Widener family, but also our growing collection of American art. With this donation, the Gallery will house one of the finest assemblages of early American furniture, and there is no such comparable and easily accessible public collection in the nation's capital. -

Facing Philadelphia: the Social Functions of Silhouettes, Miniatures, and Daguerreotypes, 1760-1860

W&M ScholarWorks Dissertations, Theses, and Masters Projects Theses, Dissertations, & Master Projects 1996 Facing Philadelphia: The social functions of silhouettes, miniatures, and daguerreotypes, 1760-1860 Anne Ayer Verplanck College of William & Mary - Arts & Sciences Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarworks.wm.edu/etd Part of the American Studies Commons, History of Art, Architecture, and Archaeology Commons, and the United States History Commons Recommended Citation Verplanck, Anne Ayer, "Facing Philadelphia: The social functions of silhouettes, miniatures, and daguerreotypes, 1760-1860" (1996). Dissertations, Theses, and Masters Projects. Paper 1539623891. https://dx.doi.org/doi:10.21220/s2-t7h6-fh38 This Dissertation is brought to you for free and open access by the Theses, Dissertations, & Master Projects at W&M ScholarWorks. It has been accepted for inclusion in Dissertations, Theses, and Masters Projects by an authorized administrator of W&M ScholarWorks. For more information, please contact [email protected]. INFORMATION TO USERS This manuscript has been reproduced from the microfilm master. UMI films the text directly from the original or copy submitted. Thus, some thesis and dissertation copies are in typewriter face, while others may be from any type of computer printer. The quality of this reproduction is dependent upon the quality of the copy submitted. Broken or indistinct print, colored or poor quality illustrations and photographs, print bleedthrough, substandard margins, and improper alignment can adversely affect reproduction. In the unlikely event that the author did not send UMI a complete manuscript and there are missing pages, these will be noted. Also, if unauthorized copyright material had to be removed, a note will indicate the deletion. -

Seasoned Greetings

SEASONED GREETINGS A QUARTERLY NEWSLETTER OF ROANOKE MONTHLY MEETING Summer Edition 2017 “While the earth remains, Seedtime and harvest, And cold and heat, And summer and winter, And day and night Shall not cease.” ~ Genesis 8:22 SUMMER AT ROANOKE FRIENDS MEETING june, july, august, september Every Sunday: 10:30 am: Meeting for Worship every sunday: following rise of worship: snacks and fellowship First Sundays: 12 noon:potluck meal following rise of meeting at noon Collection of food items for back pack program on these Sundays (when school is in session) second sundays: 12 noon: Adult Religious Education Discussions Third Sundays: !2 noon, Meeting for worship with attention to business fourth sundays: 12 noon: Varied programs of interest to friends fourth tuesdays: 7:00 until 8:00 pm: Chanting at the Meetinghouse every third saturday: 12 noon: peace vigil at roanoke city market building upcoming special events: Mid Week worship occurs once a month on Wednesdays. There is no set schedule. The dates are aanounced by email. OTHER EVENTS, AS THEY ARE SCHEDULED, WILL APPEAR THE newsLetter IS PUBLISHED 4 TIMES ON THE MEETINGHOUSE CALENDAR, AT THE MEETING- A YEAR, on THE first daY of everY HOUSE, ON OUR FACEBOOK PAGE AND ALSO WILL BE season. CIRCULATED VIA EMAILS THE autumn newsLetter WILL BE PUBLISHED on sePTEMBER 22ND, THE first daY of autumn. PLEASE NOTE THE DEADLINE FOR SUBMISSIONS FOR THE AUTUMN NEWS- LETTER IS SEPTEMBER 15TH. REGRETFULLY, SUBMISSIONS RECEIVED AFTER THAT DATE WILL NOT APPEAR IN THE AUTUMN NEWSLETTER. SOME QUERIES FOR SUMMER CARING FOR ONE ANOTHER WHAT IMPEDIMENTS DO I FIND TO REACHING OUT TO THOSE IN DISTRESS? WHAT DO I NEED TO DO TO OVERCOME THEM? AM I COMFORTABLE MAKING MY OWN NEEDS KNOWN TO MY MEETING? HOW DO WE SHARE IN THE DIVERSE JOYS AND TRANSITIONS IN EACH OTHER’S LIVES? you’re invited ! On Wednesday June 21st, Friends are invited to join Herb and Cecily for their annual Summer Solstice garden event at 2046 Knollwood Road, Roanoke Potluck at 6:00.