Book Reviews and Book Notes

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

PEAES Guide: Cliveden

PEAES Guide: Cliveden http://www.librarycompany.org/Economics/PEAESguide/cliveden.htm Keyword Search Entire Guide View Resources by Institution Search Guide Institutions Surveyed - Select One Cliveden Contact information: Researchers are advised to call ahead for an appointment to read manuscript materials: (215) 848-1777 or [email protected]. Overview: Cliveden is an historic house museum on 6 acres of landscaped grounds in the Germantown neighborhood of Philadelphia's Historic Northwest. The property was the scene of the Battle of Germantown in October, 1777, and home to the descendants of the original owner until 1972. Includes original furnishings and decorative arts, including superlative examples of colonial Philadelphia craftsmanship by James Reynolds, Jonathan Gostelowe and Thomas Affleck. Cliveden is located on the northeast corner of Germantown Avenue and Johnson Streets, north of downtown Philadelphia in Germantown. From the PA Turnpike (1-276) take exit 333( formerly Exit 25, Norristown) and follow Germantown Pike east about seven miles to Cliveden on the left. Enter from Cliveden Street. From the Schuylkill Expressway (1-76) take exit 340 (formerly Exit 32) to the Lincoln Drive. Turn right onto Johnson Street (third light) then left onto Germantown Avenue (fourth light). Take the first right onto Cliveden St. Entrance gate is on the right at the end of the first block. We urge you to take a tour of the house while you are there, and walk Germantown Avenue to see other late-18 th century houses and businesses. Resources at Cliveden available to scholars upon request: Chew family papers (Cliveden) 21 linear feet, finding aid available. -

Cliveden Bibliography

Cliveden Resources and Bibliography Updated 11/15/02 Introduction The following list has three parts: Part I lists archival and other collections—many of them very large—that tell a part of the Cliveden story. Part II lists the various research tools and resources available at Cliveden. These include reports from numerous research projects undertaken since the site was given to the National Trust in 1972, many of them in computer-readable form. Part III is an extensive bibliography of works about Cliveden or the people who lived there. Because these publications are numerous, they have been divided into categories such as “Architecture” or “Tour Guides.” There are undoubtedly many omissions, but additional items will be added as they come to our attention, in the hope that the list will one day be comprehensive. Part I: Collections Primary source materials at Cliveden Chew family library Legal library contains approximately 200 items dating from 1627 to the late eighteenth century. General library includes later legal titles plus 800 general interest titles from the eighteenth, nineteenth and early twentieth centuries. Alphabetical author listing and shelf list available. Chew family papers 40+ linear feet of standard legal document boxes plus four large map cases of containing oversize materials. Item level finding aid available. Consists primarily of Chew family papers and photographs found in house after the bulk of collection was transferred to the Historical Society of Pennsylvania in 1972. Object collections Approximately 3,000 objects dating from the mid-eighteenth century to 1972. Bulk of collection consists of furniture and other decorative arts materials, textiles, paintings and graphics. -

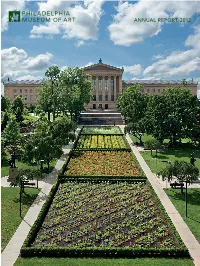

Annual Report 2012

BOARD OF TRUSTEES 4 LETTER FROM THE CHAIR 6 A YEAR AT THE MUSEUM 8 Collecting 10 Exhibiting 20 Teaching and Learning 30 Connecting and Collaborating 38 Building 44 Conserving 50 Supporting 54 Staffing and Volunteering 62 CALENDAR OF EXHIBITIONS AND EVENTS 68 FINANCIAL StATEMENTS 72 COMMIttEES OF THE BOARD OF TRUSTEES 78 SUPPORT GROUPS 80 VOLUNTEERS 83 MUSEUM StAFF 86 A REPORT LIKE THIS IS, IN ESSENCE, A SNAPSHOT. Like a snapshot it captures a moment in time, one that tells a compelling story that is rich in detail and resonates with meaning about the subject it represents. With this analogy in mind, we hope that as you read this account of our operations during fiscal year 2012 you will not only appreciate all that has been accomplished at the Philadelphia Museum of Art, but also see how this work has served to fulfill the mission of this institution through the continued development and care of our collection, the presentation of a broad range of exhibitions and programs, and the strengthening of our relationship to the com- munity through education and outreach. In this regard, continuity is vitally important. In other words, what the Museum was founded to do in 1876 is as essential today as it was then. Fostering the understanding and appreciation of the work of great artists and nurturing the spirit of creativity in all of us are enduring values without which we, individually and collectively, would be greatly diminished. If continuity—the responsibility for sustaining the things that we value most—is impor- tant, then so, too, is a commitment to change. -

Discipline, Discours

INFORMATION TO USERS This reproduction was made from a copy of a document sent to us for microfilming. While the most advanced technology has been used to photograph and reproduce this document, the quality of the reproduction is heavily dependent upon the quality of the material submitted. The following explanation of techniques is provided to help clarify markings or notations which may appear on this reproduction. 1. The sign or “target” for pages apparently lacking from the document photographed is “Missing Page(s)”. If it was possible to obtain the missing page(s) or section, they are spliced into the film along with adjacent pages. This may have necessitated cutting through an image and duplicating adjacent pages to assure complete continuity. 2. When an image on the film is obliterated with a round black mark, it is an indication of either blurred copy because of movement during exposure, duplicate copy, or copyrighted materials that should not have been filmed. For blurred pages, a good image of the page can be found in the adjacent frame. If copyrighted materials were deleted, a target note will appear listing the pages in the adjacent frame. 3. When a map, drawing or chart, etc., is part of the material being photographed, a definite method of “sectioning” the material has been followed. It is customary to begin filming at the upper left hand comer of a large sheet and to continue from left to right in equal sections with small overlaps. If necessary, sectioning is continued again—beginning below the first row and continuing on until complete. -

REVIEW. Very Well, but Decided to Go to “Goats” (The Quaker ELIZABETH FRY, QUAKER HEROINE.* Meeting House)

194 JULY, 1937 On February 4, 1798, Betsy Gurney was not feeling REVIEW. very well, but decided to go to “Goats” (the Quaker ELIZABETH FRY, QUAKER HEROINE.* meeting house). She was looking down at her pretty The Life of Elizabeth Fry, Quaker Heroine, by Janet boots when William Savery broke the dull silence “not whitney, is a book of exceptional interest, both from the by the usual drone of Quaker preaching, but by a voice literary standpoint, and because it deals with the life resonant and musical, with something- definite to sag and and work of one of the greatest and most remarkable grkit feeling in saying it. women of the eighteenth century. “ It was, in sober fact, the crisis of her life.” “ ‘I am Mrs. Fry was the fourth child of the family of twelve to be a Quaker.’ That was it, That was what she had of John Gurney and Catherine Bell, and our first glimpse been waitinp for. Something to do. She looked around to of them gives little indication of the future life of Elizabeth. see-if therevwas no one she-could help taow, to-day-and The escapade of the seven girls defying the coachman her eye fell at once upon the salient spot. The country-side of the Norwich coach and holding it up indicates the swarmed with children totally untaught.” temper of the family. “All of them horsewomen, they Elizabeth set to work and soon gathered 70 or more hew that the four great horses, snorting and smoking, children in the laundry. ‘‘ Meanwhile the family gathered .would not run them down if they maintained an unbroken But not many girls could have done it. -

Information to Users

INFORMATION TO USERS This manuscript has been reproduced from the microfilm master. UMI films the text directly from the original or copy submitted. Thus, some thesis and dissertation copies are in typewriter face, while others may be from any type of computer printer. The quality of this reproduction is dependent upon the quality of the copy subm itted. Broken or indistinct print, colored or poor quality illustrations and photographs, print bleedthrough, substandard margins, and improper alignment can adversely affect reproduction. In the unlikely event that the author did not send UMI a complete manuscript and there are missing pages, these will be noted. Also, if unauthorized copyright material had to be removed, a note will indicate the deletion. Oversize materials (e.g., maps, drawings, charts) are reproduced by sectioning the original, beginning at the upper left-hand comer and continuing from left to right in equal sections with small overlaps. Photographs included in the original manuscript have been reproduced xerographically in this copy. Higher quality 6* x 9" black and white photographic prints are available for any photographs or illustrations appearing in this copy for an additional charge. Contact UMI directly to order. ProQuest Information and Learning 300 North Zeeb Road, Ann Arbor, Ml 48106-1346 USA 800-521-0600 Reproduced with permission of the copyright owner. Further reproduction prohibited without permission. Reproduced with permission of the copyright owner. Further reproduction prohibited without permission. NOTE TO USERS This reproduction is the best copy available. UMI Reproduced with permission of the copyright owner. Further reproduction prohibited without permission. Reproduced with permission of the copyright owner. -

THE UEOR({E :;:; , \- \UY ~L'lxsiox, '-'-,, ,N,-,-1L1Y

THE UEOR({E :;:;_, \-_\UY ~L'lXSIOX, '-'-,, _,n,-,-1L1Y. (;n,,, Fl A'-'I•. ~r_,., .... B1-11,T 1x 1:-:211. A GENEALOGICAL AND BIOGRAPHICAL RECORD OF TJIE SA VERY FAl\!IILIES (SAVORY AND SAVARY) .IND Ul•' TIIE SEVERY FAlVIIL Y (SEYEt:rr, SAVEHY, SAV<Ha·, AND 8AL\1tY) DESCJ•:NDED FHOM IUHLY DDll<.R.\NTS TO Nl~W J!XGL.\NI> AND PHILADELPHIA WITH INTRODl'CTORY ARTICLES ON THE ORIGIN AND JIUiTORY OF THE NA~ms, AN!> OF ENGLl:SII F.IM!LIES OF TUI! N.Dm SAVEHY IN ITS VA HIOUS FOIDIS; ,\ I>In'.111.EI> SKETC'II OF Tim UFE ANll LABOitS OJ,' WILJ.Ll:ir SAVEHY, ~IJ'.'/18TEI: OF Tim c:osp1,;r, [:"< TUE SO('JETY OF FIUl!:'.\l>Sj AXI> .\l'l'EN[>IXES co:-.;T,\IXING AX .IC'l'(WNT ()F S.\ nm y's INVF,NTlflX OF nm STE.DI ENnJ:-.;E, ANJ> I•:XTit.lCTS FIW~I 1-::,.;n- 1.1,-;11, :"<l•:W EN<H,.\NI>, .IXD BAHll.\l>OES ltECOHVR JrnLATIN(; TO F.DIILJE,-; OF BUTH N.\~ms. 11,· 01' .1NNAl'OUS ROYAL, :N°OVA SCOTIA, ,JFDHE 01" THE COUNTY COURTS OF NOVA SCOTIA. ASSISTED I:'< THE GENEALOGY HY MISS LYDIA A. SAVARY, I'' OF EAST WAl1EIIAM, 3IA~S. Mea me virtn::;, et saneta orncula Divnm, Cu!(n:itlque patres, tun terrls dhlltn. fa11111, Conjunxere tihl. YIRG., ,·EN. viii. 131. BOSTON: 'l'IIE COLLINS PRESS. 18!l3. PREFACE. BESIDES my recognized assistant in the compilation of this Genealogy, and those to whom I acknowledged my obligations in the '' New England Historical and Genealogical Register" for Octo ber, 1887, I am imlehtetl to Dr. -

The House Most Widely Associated with Benjamin Franklin (1706–1790) Is the One That He Built for His Family in Philadelphia, I

The House that Franklin Built by Page Talbott he house most widely associated with Benjamin Franklin a house of his own, having previously resided with his family in smaller (1706–1790) is the one that he built for his family in rented dwellings in the neighborhood. T Philadelphia, in a quiet, spacious courtyard off Market Street Like Jefferson at Monticello, Franklin had a hand in the design of between Third and Fourth Streets. Newly returned from his seven-year the house, though he spent the actual building period as colonial stay in London in late 1762, Benjamin Franklin decided it was time for agent in England. His wife, Deborah (1708–1774), oversaw the con- struction, while Franklin sent back Continental goods and a steady stream of advice and queries. Although occupied with matters of busi- ness, civic improvement, scientific inquiry, and affairs of state, he was never too busy to advise his wife and daughter about fashion, interior decoration, and household pur- chases. Franklin’s letters to his wife about the new house — and her responses — offer extraordinary detail about its construction and embellishment. The house was razed in 1812 to make room for a street and several smaller houses, but these letters, together with Gunning Bedford’s 1766 fire insurance survey, help us visualize this elegant mansion, complete with wainscoting, columns and pilasters, pediments, dentil work, frets and cornices.1 On his return to Philadelphia in November 1762, Franklin and his wife had the opportunity to plan and start building their first house, only a few steps from where they had first laid eyes on each other. -

Here Was an Interesting Diversion

Rebecca Scattergood Savery 1770-1855 20 North Fifth Street Philadelphia, Pennsylvania Rebecca Scattergood Savery • The Widows of North Fifth Street • Roadmaps • The Watson Family • The Scattergood Family • Widow Scattergood and Her Sons • The Head Family • Marriage of John Scattergood and Elizabeth Head • Death of John Scattergood • The Baker Household • Marriage of Rebecca Scattergood and Thomas Savery • Children of Thomas and Rebecca Savery • The Savery Businesswomen • The Quaker Ministers/Tanners • Pegg’s Run • Rebecca Scattergood Savery’s Death and Legacy • The Savery-Scattergood Quilts Friendship Quilt - American Folk Art Museum Star Quilt - International Quilt Museum Medallion Quilt - International Quilt Museum Endnotes • John Scattergood Inventory • Rebecca Scattergood & Thomas Savery Marriage Certificate • Deeds - Scattergood Complex at North Front Street, Margaretta Street & Pegg’s Run • 1790-1850 Census Records • Rebecca & Elisabeth Savery Real Estate • A Cresson-Scattergood-Savery Connection - Watson Family • Descendant Tree - New Jersey Scattergoods • Endnotes for Rebecca Scattergood Savery • Endnotes for the Quaker Ministers/Tanners Thomas Scattergood and William Savery • Endnotes for the Savery/Scattergood/Cresson Quilts • End Page - What Would Rebecca Think! Nancy Ettensperger - April 2020 Rebecca Scattergood Savery - Page 1 Ancestors & Others The Widows of North Fifth Street, Philadelphia, Pennsylvania William F. Hansell 1813-1881 is in a family line I have been investigating. In the 1850 census, I noticed that his close neighbors on North Fifth Street were all widows. Here was an interesting diversion. 30/32 North Fifth - Elizabeth Witmer nee Eckfeldt came into possession of this property from her grandfather Jacob Eckfeldt, the famous blacksmith whose family is associated with the U.S. Mint. Grandpa Eckfeldt had operated this property as a tavern. -

John Cadwalader (General) - Wikipedia

John Cadwalader (general) - Wikipedia https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/John_Cadwalader_(general) John Cadwalader (January 10, 1742 – February 10, 1786) was a John Cadwalader commander of Pennsylvania troops during the American Revolutionary War and served under George Washington. He was with Washington during the Delaware River crossing and the Battle of Trenton and at Valley Forge. Early life Revolutionary War Later life Furniture Family tree Notes Philadelphia Museum of Art References John and Elizabeth Lloyd External links Cadwalader and their Daughter Anne (1772) by Charles Willson Peale. Born January 10, 1742 John Cadwalader was born in Trenton, New Jersey of Quaker parentage, Trenton, New Jersey the eldest son of Thomas Cadwalader (1707–1779) and Hannah Lambert, Died February 10, 1786 his wife.[1][2] In 1750, the Cadwalader family removed to Philadelphia (aged 44) where John and Lambert Cadwalader, his brother, were merchants. Kent County, Maryland On September 25, 1768, John Cadwalader married Elizabeth Lloyd Occupation Merchant (1742–1776), the daughter of Edward Lloyd, of Talbot County, Maryland. Her brother, Edward Lloyd IV, was a delegate to the Continental Congress Spouse(s) Elizabeth Lloyd for Maryland.[3] Their daughter, Maria Cadwalader (1776–1811), married Williamina Bond Samuel Ringgold, who became a congressman representing Maryland. Two Children Anne, b: 1771 of their sons, Samuel Ringgold and Cadwalader Ringgold, had Elizabeth, b: 1774 distinguished military careers. Maria, b: 1776 Thomas, b: 1779 Frances, b: 1781 John, -

Tilt-Top Tables Commodities I.Pdf

INFORMATION TO USERS This manuscript has been reproduced from the microfilm master. UMI films the text directly from the original or copy submitted. Thus, some thesis and dissertation copies are in typewriter face, while others may be from any type of computer printer. The quality of this reproduction is dependent upon the quality of the copy subm itted. Broken or indistinct print, colored or poor quality illustrations and photographs, print bleedthrough, substandard margins, and improper alignment can adversely affect reproduction. In the unlikely event that the author did not send UMI a complete manuscript and there are missing pages, these will be noted. Also, if unauthorized copyright material had to be removed, a note will indicate the deletion. Oversize materials (e.g., maps, drawings, charts) are reproduced by sectioning the original, beginning at the upper left-hand comer and continuing from left to right in equal sections with small overlaps. Photographs included in the original manuscript have been reproduced xerographically in this copy. Higher quality 6" x 9" black and white photographic prints are available for any photographs or illustrations appearing in this copy for an additional charge. Contact UMI directly to order. ProQuest Information and Learning 300 North Zeeb Road, Ann Arbor, Ml 48106-1346 USA 800-521-0600 Reproduced with permission of the copyright owner. Further reproduction prohibited without permission. Reproduced with permission of the copyright owner. Further reproduction prohibited without permission. NOTE TO USERS Copyrighted materials in this document have not been filmed at the request of the author. They are available for consultation at the author’s university library. -

The Hope Expressed on Page 63 of Our Last Volume That Henry J

Cumnf Books of interest to Friends may be purchased at the Friends' Book Centre, Euston Road,London, N.W.I. Friends' Book and Tract Committee, 144 East 20th Street, New York City. Friends' Book Store, 302 Arch Street, Philadelphia, Pa. Friends' Book and Supply House, Richmond, Ind. Many of the books in D may be borrowed by Friends. Apply to the Librarian, Friends House, Euston Road, London, N.W.I. The hope expressed on page 63 of our last volume that Henry J. Cadbury's sketch of the " Sloop Folk" might be available to our readers was shortly afterwards realised so far that the sketch appeared in F.Q.E. for Tenth Month, 1925, worthily occupying thirty pages of the publication. Further notices in literature of Friends in Norway appear in footnotes. (This issue of the Quarterly is brim-full of valuable historical matter.) In The Harvard Theological Review, October, 1925, appeared an article by Henry J. Cadbury, on " The Norwegian Quakers of 1825," containing a somewhat similar account, more fully presented, with fuller footnotes. Also see Bulletin F.H.A., Spring, 1926. The issue of the F.Q.E. for First Month, 1926, contains an article by Albert J. Crosfield, on " A Memorable Visit to Friends in Norway in 1853." _______ What a change in the presentation of biographies of Friends during the course of the years ! Eighty-eight years ago, in 1837, appeared in Philadelphia, the first volume of " Friends' Library," edited by William and Thomas Evans. In this volume there was a memoir of William Savery, written by Jonathan Evans.