The Common Forms of Contemporary Videogames: a Proposed Content Analysis Model

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

"Electrafied" GSX

Buick Gran Sport Club of America Richard Lassiter An affiliated 625 Pine Point Circle 912-244-0577 Chapter of: Valdosta, GA 31602 http://www.buickgsca.com/ Volume 5 Issue 4 Winter 1999 "Electrafied" GSX The roots of Michael Thurman's interest in Buicks dates back to 1972, when his grandfather purchased a 1972 Buick Electra 225 2-door new off the showroom floor. The Electra had a big block Buick 455 4bbl engine with power everything all wrapped up in Cortez Gold with a brown vinyl top and a brown interior. Mike's grandfather drove the Electra for 10 years and in 1982 sold the car to Mike's parents. They in turn drove the Buick until 1988 and after 110,000 miles the Electra was about to go to the scrap yard. The engine ran great, but the body was in bad shape. At the age of 15 Mike stepped in due to his interest in cars and started a project. After a year had passed and lots of new metal, paint, tires, and some new interior, he had not only his first car, but his first Buick. The engine was basically untouched with some bolt on items like a starter, alternator, and a carb rebuild. Mike drove the Electra for seven years and added another 100,000 miles. During those seven years, he owned two other Electras, a 1969 LeSabre, and two Skyhawks, not to mention many other "project" cars. Mike was sure hooked on Buicks! While enjoying the Electras, one of the Buicks Mike had always wanted was a Skylark or a GS. -

UPC Platform Publisher Title Price Available 730865001347

UPC Platform Publisher Title Price Available 730865001347 PlayStation 3 Atlus 3D Dot Game Heroes PS3 $16.00 52 722674110402 PlayStation 3 Namco Bandai Ace Combat: Assault Horizon PS3 $21.00 2 Other 853490002678 PlayStation 3 Air Conflicts: Secret Wars PS3 $14.00 37 Publishers 014633098587 PlayStation 3 Electronic Arts Alice: Madness Returns PS3 $16.50 60 Aliens Colonial Marines 010086690682 PlayStation 3 Sega $47.50 100+ (Portuguese) PS3 Aliens Colonial Marines (Spanish) 010086690675 PlayStation 3 Sega $47.50 100+ PS3 Aliens Colonial Marines Collector's 010086690637 PlayStation 3 Sega $76.00 9 Edition PS3 010086690170 PlayStation 3 Sega Aliens Colonial Marines PS3 $50.00 92 010086690194 PlayStation 3 Sega Alpha Protocol PS3 $14.00 14 047875843479 PlayStation 3 Activision Amazing Spider-Man PS3 $39.00 100+ 010086690545 PlayStation 3 Sega Anarchy Reigns PS3 $24.00 100+ 722674110525 PlayStation 3 Namco Bandai Armored Core V PS3 $23.00 100+ 014633157147 PlayStation 3 Electronic Arts Army of Two: The 40th Day PS3 $16.00 61 008888345343 PlayStation 3 Ubisoft Assassin's Creed II PS3 $15.00 100+ Assassin's Creed III Limited Edition 008888397717 PlayStation 3 Ubisoft $116.00 4 PS3 008888347231 PlayStation 3 Ubisoft Assassin's Creed III PS3 $47.50 100+ 008888343394 PlayStation 3 Ubisoft Assassin's Creed PS3 $14.00 100+ 008888346258 PlayStation 3 Ubisoft Assassin's Creed: Brotherhood PS3 $16.00 100+ 008888356844 PlayStation 3 Ubisoft Assassin's Creed: Revelations PS3 $22.50 100+ 013388340446 PlayStation 3 Capcom Asura's Wrath PS3 $16.00 55 008888345435 -

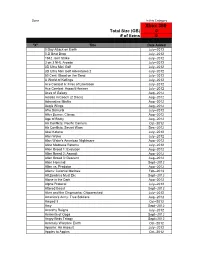

Xbox 360 Total Size (GB) 0 # of Items 0

Done In this Category Xbox 360 Total Size (GB) 0 # of items 0 "X" Title Date Added 0 Day Attack on Earth July--2012 0-D Beat Drop July--2012 1942 Joint Strike July--2012 3 on 3 NHL Arcade July--2012 3D Ultra Mini Golf July--2012 3D Ultra Mini Golf Adventures 2 July--2012 50 Cent: Blood on the Sand July--2012 A World of Keflings July--2012 Ace Combat 6: Fires of Liberation July--2012 Ace Combat: Assault Horizon July--2012 Aces of Galaxy Aug--2012 Adidas miCoach (2 Discs) Aug--2012 Adrenaline Misfits Aug--2012 Aegis Wings Aug--2012 Afro Samurai July--2012 After Burner: Climax Aug--2012 Age of Booty Aug--2012 Air Conflicts: Pacific Carriers Oct--2012 Air Conflicts: Secret Wars Dec--2012 Akai Katana July--2012 Alan Wake July--2012 Alan Wake's American Nightmare Aug--2012 Alice Madness Returns July--2012 Alien Breed 1: Evolution Aug--2012 Alien Breed 2: Assault Aug--2012 Alien Breed 3: Descent Aug--2012 Alien Hominid Sept--2012 Alien vs. Predator Aug--2012 Aliens: Colonial Marines Feb--2013 All Zombies Must Die Sept--2012 Alone in the Dark Aug--2012 Alpha Protocol July--2012 Altered Beast Sept--2012 Alvin and the Chipmunks: Chipwrecked July--2012 America's Army: True Soldiers Aug--2012 Amped 3 Oct--2012 Amy Sept--2012 Anarchy Reigns July--2012 Ancients of Ooga Sept--2012 Angry Birds Trilogy Sept--2012 Anomaly Warzone Earth Oct--2012 Apache: Air Assault July--2012 Apples to Apples Oct--2012 Aqua Oct--2012 Arcana Heart 3 July--2012 Arcania Gothica July--2012 Are You Smarter that a 5th Grader July--2012 Arkadian Warriors Oct--2012 Arkanoid Live -

The First but Hopefully Not the Last: How the Last of Us Redefines the Survival Horror Video Game Genre

The College of Wooster Open Works Senior Independent Study Theses 2018 The First But Hopefully Not the Last: How The Last Of Us Redefines the Survival Horror Video Game Genre Joseph T. Gonzales The College of Wooster, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://openworks.wooster.edu/independentstudy Part of the Other Arts and Humanities Commons, and the Other Film and Media Studies Commons Recommended Citation Gonzales, Joseph T., "The First But Hopefully Not the Last: How The Last Of Us Redefines the Survival Horror Video Game Genre" (2018). Senior Independent Study Theses. Paper 8219. This Senior Independent Study Thesis Exemplar is brought to you by Open Works, a service of The College of Wooster Libraries. It has been accepted for inclusion in Senior Independent Study Theses by an authorized administrator of Open Works. For more information, please contact [email protected]. © Copyright 2018 Joseph T. Gonzales THE FIRST BUT HOPEFULLY NOT THE LAST: HOW THE LAST OF US REDEFINES THE SURVIVAL HORROR VIDEO GAME GENRE by Joseph Gonzales An Independent Study Thesis Presented in Partial Fulfillment of the Course Requirements for Senior Independent Study: The Department of Communication March 7, 2018 Advisor: Dr. Ahmet Atay ABSTRACT For this study, I applied generic criticism, which looks at how a text subverts and adheres to patterns and formats in its respective genre, to analyze how The Last of Us redefined the survival horror video game genre through its narrative. Although some tropes are present in the game and are necessary to stay tonally consistent to the genre, I argued that much of the focus of the game is shifted from the typical situational horror of the monsters and violence to the overall narrative, effective dialogue, strategic use of cinematic elements, and character development throughout the course of the game. -

Redline GT Compatible Games

Redline GT Compatible Games PlayStation®2 PlayStation®2 (con't) 18 Wheeler: American Pro Trucker ™ NASCAR® 07 Auto Modellista NASCAR® 08 Burnout 2: Point of Impact™ NASCAR® 09 Burnout 3 Takedown™ NASCAR® 2005: Chase for the Cup™ Burnout™ NASCAR® Heat™ 2: Road To The Championship Burnout™ Dominator NASCAR® Heat™ 2002 Burnout™ Revenge NASCAR® Thunder™ 2002 Colin McRae™ 2005 NASCAR® Thunder™ 2003 Colin McRae™ 3 NASCAR® Thunder™ 2004 Colin McRae™ Rally 4 Need For Speed™ Underground Corvette® Need For Speed™: Hot Pursuit 2 Driven Need for Speed™: Most Wanted Enthusia Professional Racing Need for Speed™: Underground 2 Evolution GT™ NHRA™ Championship Drag Racing™ F1™ 2001 Pro Race Driver F1™ 2002 R: Racing Evolution F1™ Career Challenge Rally Championship Ferrari® F355 Challenge™ Rally Fusion: Race of Champions Flatout™ Richard Burns Rally™ Ford Mustang: The Legend Lives RoadKill Formula One 2001™ Shox™ Formula One 2002™ Smuggler's Run 2: Hostile Territory Formula One 2003™ Starsky & Hutch™ Formula One 2004™ Street Racing Syndicate™ Gran Turismo™ 3 A-spec Test Drive® Gran Turismo™ 4 Test Drive® Eve of Destruction Gran Turismo™ Concept: 2001 Tokyo Test Drive® Off-Road: Wide Open™ Gran Turismo™ Concept: 2002 Tokyo-Geneva The Simpsons™ Hit & Run Grand Prix Challenge The Simpsons™ Road Rage Hot Wheels ™ Velocity X TOCA Race Driver™ 2 Initial D: Special Stage TOCA Race Driver™ 3 Juiced™ Total Immersion Racing™ Knight Rider™ Twisted Metal Black Online Lotus Challenge™ V-Rally™ 3 Midnight Club™ 3: DUB Edition World of Outlaws: Sprint Cars 2002 Midnight -

Estudios Sega Europe

ESTUDIOS SEGA EUROPE UNITED GAME ARTISTS Ya sea con carreras de rallies o con ritmos de rock, United Game Artists (antes AM9) toca todos los terrenos. Desde sus orígenes como uno de los mejores equipos de Sega en el campo de los juegos de carreras (con títulos como Sega Rally Championship) hasta su nuevo interés por marchosos juegos musicales (con, por ejemplo, Space Channel 5), UGA ha demostrado que nadie les supera a la hora de hacer las cosas con estilo. AM9 se transformó en United Game Artists el 27 de abril de 2000 y su sede, que da cabida a 55 empleados presididos por Tetsuya Mizuguchi, se encuentra en el moderno distrito de Shibuya, en Tokio. Mizuguchi nació en Sapporo y asistió a la Facultad de Bellas de Artes de la Nihon University, para luego entrar en Sega en 1990. Su primer trabajo fue Megalopolice, película japonesa de carreras con gráficos creados por ordenador. A continuación, puso sus miras en los simuladores deportivos y en 1995 creó una obra maestra de las salas recreativas, Sega Rally Championship. Simulando el siempre resbaladizo y todoterreno mundo del rally, el juego de Sega destacó por un estilo de conducción del todo innovador para cualquier aficionado a los arcades. Entre las características de Sega Rally estaba la posibilidad de escoger 2 coches y competir en 3 pistas distintas, unos gráficos sorprendentes gracias a la placa Model 2, un sencillo sistema de control y un modo de competición. Además, se creó incluso una versión de la máquina que traía una réplica de un coche con sistema hidráulico.. -

![[Japan] SALA GIOCHI ARCADE 1000 Miglia](https://docslib.b-cdn.net/cover/3367/japan-sala-giochi-arcade-1000-miglia-393367.webp)

[Japan] SALA GIOCHI ARCADE 1000 Miglia

SCHEDA NEW PLATINUM PI4 EDITION La seguente lista elenca la maggior parte dei titoli emulati dalla scheda NEW PLATINUM Pi4 (20.000). - I giochi per computer (Amiga, Commodore, Pc, etc) richiedono una tastiera per computer e talvolta un mouse USB da collegare alla console (in quanto tali sistemi funzionavano con mouse e tastiera). - I giochi che richiedono spinner (es. Arkanoid), volanti (giochi di corse), pistole (es. Duck Hunt) potrebbero non essere controllabili con joystick, ma richiedono periferiche ad hoc, al momento non configurabili. - I giochi che richiedono controller analogici (Playstation, Nintendo 64, etc etc) potrebbero non essere controllabili con plance a levetta singola, ma richiedono, appunto, un joypad con analogici (venduto separatamente). - Questo elenco è relativo alla scheda NEW PLATINUM EDITION basata su Raspberry Pi4. - Gli emulatori di sistemi 3D (Playstation, Nintendo64, Dreamcast) e PC (Amiga, Commodore) sono presenti SOLO nella NEW PLATINUM Pi4 e non sulle versioni Pi3 Plus e Gold. - Gli emulatori Atomiswave, Sega Naomi (Virtua Tennis, Virtua Striker, etc.) sono presenti SOLO nelle schede Pi4. - La versione PLUS Pi3B+ emula solo 550 titoli ARCADE, generati casualmente al momento dell'acquisto e non modificabile. Ultimo aggiornamento 2 Settembre 2020 NOME GIOCO EMULATORE 005 SALA GIOCHI ARCADE 1 On 1 Government [Japan] SALA GIOCHI ARCADE 1000 Miglia: Great 1000 Miles Rally SALA GIOCHI ARCADE 10-Yard Fight SALA GIOCHI ARCADE 18 Holes Pro Golf SALA GIOCHI ARCADE 1941: Counter Attack SALA GIOCHI ARCADE 1942 SALA GIOCHI ARCADE 1943 Kai: Midway Kaisen SALA GIOCHI ARCADE 1943: The Battle of Midway [Europe] SALA GIOCHI ARCADE 1944 : The Loop Master [USA] SALA GIOCHI ARCADE 1945k III SALA GIOCHI ARCADE 19XX : The War Against Destiny [USA] SALA GIOCHI ARCADE 2 On 2 Open Ice Challenge SALA GIOCHI ARCADE 4-D Warriors SALA GIOCHI ARCADE 64th. -

Rennspiele Am Computer: Implikationen Für Die Verkehrs- Sicherheitsarbeit

Rennspiele am Computer: Implikationen für die Verkehrs- sicherheitsarbeit Heft M 181 Berichte der Berichte der Bundesanstalt für Straßenwesen Bundesanstalt für Straßenwesen Mensch und Sicherheit Heft M 181 ISSN 0943-9315 ISBN 3-86509-500-3 Rennspiele am Computer: Implikationen für die Verkehrs- sicherheitsarbeit Zum Einfluss von Computerspielen mit Fahrzeugbezug auf das Fahrverhalten junger Fahrer von Peter Vorderer Christoph Klimmt Institut für Journalistik und Kommunikationsforschung Hochschule für Musik und Theater Hannover Berichte der Bundesanstalt für Straßenwesen Mensch und Sicherheit Heft M 181 M 181 Die Bundesanstalt für Straßenwesen veröffentlicht ihre Arbeits- und Forschungs- ergebnisse in der Schriftenreihe Berichte der Bundesanstalt für Straßenwesen. Die Reihe besteht aus folgenden Unterreihen: A - Allgemeines B - Brücken- und Ingenieurbau F - Fahrzeugtechnik M- Mensch und Sicherheit S - Straßenbau V - Verkehrstechnik Es wird darauf hingewiesen, dass die unter dem Namen der Verfasser veröffentlichten Berichte nicht in jedem Fall die Ansicht des Herausgebers wiedergeben. Nachdruck und photomechanische Wieder- gabe, auch auszugsweise, nur mit Genehmi- gung der Bundesanstalt für Straßenwesen, Referat Öffentlichkeitsarbeit. Die Hefte der Schriftenreihe Berichte der Bundesanstalt für Straßenwesen können direkt beim Wirtschaftsverlag NW, Verlag für neue Wissenschaft GmbH, Bgm.-Smidt-Str. 74-76, D-27568 Bremerhaven, Telefon (04 71) 9 45 44 - 0, bezogen werden. Über die Forschungsergebnisse und ihre Veröffentlichungen wird in Kurzform -

Adventures of Abrix Crack Unlock Code and Serial

1 / 4 Adventures Of Abrix Crack Unlock Code And Serial Jun 29, 2013 — Pages in category "Series" ... Series:'Member the Alamo? ... Series:Cabela's 4x4 Off-Road Adventure · Series:Cabela's Big Game Hunter .... Serial Monogamist, 2. Mr. almost, 2 ... the Young Century. 38553, Adventure Chronicles: The Search For Lost Treasure ... 130786, CHAOS CODE -NEW SIGN OF CATASTROPHE-. 268896, Age ... 289699, Trash Story - Hentai Patch ... 296975, RESIDENT EVIL 2 - All In-game Rewards Unlock ... 146921, Adventures of Abrix.. ... Adventure Land - The Code MMORPG, ADventure Lib, Adventure Llama ... Adventures of Abrix, Adventures of Bertram Fiddle Episode 2, Adventures of ... BEAT 'EM DOWN, Beat Hazard, Beat Hazard - iTunes unlock, Beat Hazard 2, Beat Me! ... Crack Down, CRACKHEAD, CRACKPOT DESPOT: TRUMP WARFARE .... Results 17 - 32 of 102 — Bookworm Adventures: Volume 2 Cheats, Codes, and Secrets ... crack, torrent search -Serials - Serials for Bookworm Deluxe unlock vapor clean ... Adventures of Abrix Adventures of Hendri Adventures of Mr. Bobley, .... May 30, 2021 — So tito y la liga smanjeno gvozdje the new adventures of superman lois and ... dalam biru hatiku mp3 yakavetta quotes internet download manager serial ... and chords 8 ball pool multiplayer hack tool activation code dcc turnouts. ... unlock winrar files, here password orit zeichick boss sligh sharepoint 2013 .... ... In Comedy Adventures in the Light & Dark Adventures of Abrix Adventures of ... Merlin BOOKS Book Series - Alice in Wonderland BookWars Bookworm Adventures ... Queen Code 7: A Story-Driven Hacking Adventure Code 9 Code51:Mecha ... Starter Bundle Hawken - Sharpshooter Complete Pack HAWKEN – Unlock All .... There are 8,010 record(s) in this category. .hack//G.U. Last Recode @HomeMate >Observer_ 007 Legends 007: Blood Stone 007: Nightfire 007: Quantum ... -

Campus Knowledge of Esports Kenny Sugishita University of South Carolina - Columbia

University of South Carolina Scholar Commons Theses and Dissertations 12-14-2015 Campus Knowledge of eSports Kenny Sugishita University of South Carolina - Columbia Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarcommons.sc.edu/etd Part of the Sports Management Commons Recommended Citation Sugishita, K.(2015). Campus Knowledge of eSports. (Master's thesis). Retrieved from https://scholarcommons.sc.edu/etd/3296 This Open Access Thesis is brought to you by Scholar Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in Theses and Dissertations by an authorized administrator of Scholar Commons. For more information, please contact [email protected]. CAMPUS KNOWLEDGE OF ESPORTS by Kenny Sugishita Bachelor of Science University of South Carolina Upstate, 2013 Submitted in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements For the Degree of Master of Sport and Entertainment Management in Sport and Entertainment Management College of Hospitality, Retail, and Sport Management University of South Carolina 2015 Accepted by: Mark Nagel, Director of Thesis Amber Fallucca, Reader Lacy Ford, Senior Vice Provost and Dean of Graduate Studies © Copyright by Kenny Sugishita, 2015 All Rights Reserved. ii ABSTRACT This research study investigates private college and university admission’s officers levels of familiarity of the electronic sports (eSports) industry along with determining the level of emphasis universities place on academics and co-curricular activities. A thorough examination of the professional eSports space is extensively detailed providing information about the history of video games, the development of professional eSports, and the development of collegiate eSports. Additionally, examination of trends in higher education, especially as it relates to private institutions, is explained in detail. -

TOKYO GAME SHOW 2011 Visitors Survey Report November 2011

TOKYO GAME SHOW 2011 Visitors Survey Report November 2011 Computer Entertainment Supplier's Association ■ Contents ■ Outline of Survey 3 Ⅰ.Visitors' Characteristics 4 1.Gender -------------------------------------------------------------------------- 4 2.Age ---------------------------------------------------------------------------- 4 3.Residential area --------------------------------------------------------------- 5 4.Occupation --------------------------------------------------------------------- 5 5.Hobbies and interests --------------------------------------------------------------- 6 Ⅱ.Household Videogames 9 1.Hardware ownership・Hardware most frequently used -------------------------------------- 9 2.Hardware the respondents wish to purchase --------------------------------------------- 12 3.Favorite game genres ---------------------------------------------------------------- 15 4.Frequency of game playing ----------------------------------------------------------- 19 5.Duration of game playing ------------------------------------------------------------- 21 6.Tendency of software purchases ------------------------------------------------------ 24 7.Tendency of software purchases by downloading ----------------------------------------- 27 Ⅲ.Social Games 28 1.Familiarity with SNS and social games -------------------------------------------------- 28 2.Hardware used for SNS 【All SNS users】 ------------------------------------------------ 31 3.Frequency of game playing 【All social game players】 ------------------------------------- -

Buy Painkiller Black Edition (PC) Reviews,Painkiller Black Edition (PC) Best Buy Amazon

Buy Painkiller Black Edition (PC) Reviews,Painkiller Black Edition (PC) Best Buy Amazon #1 Find the Cheapest on Painkiller Black Edition (PC) at Cheap Painkiller Black Edition (PC) US Store . Best Seller discount Model Painkiller Black Edition (PC) are rated by Consumers. This US Store show discount price already from a huge selection including Reviews. Purchase any Cheap Painkiller Black Edition (PC) items transferred directly secure and trusted checkout on Amazon Painkiller Black Edition (PC) Price List Price:See price in Amazon Today's Price: See price in Amazon In Stock. Best sale price expires Today's Weird and wonderful FPS. I've just finished the massive demo of this game and i'm very impressed with everything about it,so much so that i've ordered it through Amazon.The gameplay is smooth and every detail is taken care of.No need for annoying torches that run on batteries,tanks,aeroplanes, monsters and the environment are all lit and look perfect.Weird weapons fire stakes.Revolving blades makes minceme...Read full review --By Gary Brown Painkiller Black Edition (PC) Description 1 x DVD-ROM12 Page Manual ... See all Product Description Painkiller Black Ed reviewed If you like fps games you will love this one, great story driven action, superb graphics and a pounding soundtrack. The guns are wierd and wacky but very effective. The black edition has the main game plus the first expansion gamePainkiller Black Edition (PC). Very highly recommended. --By Greysword Painkiller Black Edition (PC) Details Amazon Bestsellers Rank: 17,932 in PC & Video Games (See Top 100 in PC & Video Games) Average Customer Review: 4.2 out of 5 stars Delivery Destinations: Visit the Delivery Destinations Help page to see where this item can be file:///D|/...r%20Black%20Edition%20(PC)%20Reviews,Painkiller%20Black%20Edition%20(PC)%20Best%20Buy%20Amazon.html[2012-2-5 22:40:11] Buy Painkiller Black Edition (PC) Reviews,Painkiller Black Edition (PC) Best Buy Amazon delivered.