Thirty Years of Sino-Saudi Relations

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Gawc Link Classification FINAL.Xlsx

High Barcelona Beijing Sufficiency Abu Dhabi Singapore sufficiency Boston Sao Paulo Barcelona Moscow Istanbul Toronto Barcelona Tokyo Kuala Lumpur Los Angeles Beijing Taiyuan Lisbon Madrid Buenos Aires Taipei Melbourne Sao Paulo Cairo Paris Moscow San Francisco Calgary Hong Kong Nairobi New York Doha Sydney Santiago Tokyo Dublin Zurich Tokyo Vienna Frankfurt Lisbon Amsterdam Jakarta Guangzhou Milan Dallas Los Angeles Hanoi Singapore Denver New York Houston Moscow Dubai Prague Manila Moscow Hong Kong Vancouver Manila Mumbai Lisbon Milan Bangalore Tokyo Manila Tokyo Bangkok Istanbul Melbourne Mexico City Barcelona Buenos Aires Delhi Toronto Boston Mexico City Riyadh Tokyo Boston Munich Stockholm Tokyo Buenos Aires Lisbon Beijing Nanjing Frankfurt Guangzhou Beijing Santiago Kuala Lumpur Vienna Buenos Aires Toronto Lisbon Warsaw Dubai Houston London Port Louis Dubai Lisbon Madrid Prague Hong Kong Perth Manila Toronto Madrid Taipei Montreal Sao Paulo Montreal Tokyo Montreal Zurich Moscow Delhi New York Tunis Bangkok Frankfurt Rome Sao Paulo Bangkok Mumbai Santiago Zurich Barcelona Dubai Bangkok Delhi Beijing Qingdao Bangkok Warsaw Brussels Washington (DC) Cairo Sydney Dubai Guangzhou Chicago Prague Dubai Hamburg Dallas Dubai Dubai Montreal Frankfurt Rome Dublin Milan Istanbul Melbourne Johannesburg Mexico City Kuala Lumpur San Francisco Johannesburg Sao Paulo Luxembourg Madrid Karachi New York Mexico City Prague Kuwait City London Bangkok Guangzhou London Seattle Beijing Lima Luxembourg Shanghai Beijing Vancouver Madrid Melbourne Buenos Aires -

Prometric Combined Site List

Prometric Combined Site List Site Name City State ZipCode Country BUENOS AIRES ARGENTINA LAB.1 Buenos Aires ARGENTINA 1006 ARGENTINA YEREVAN, ARMENIA YEREVAN ARMENIA 0019 ARMENIA Parkus Technologies PTY LTD Parramatta New South Wales 2150 Australia SYDNEY, AUSTRALIA Sydney NEW SOUTH WALES 2000 NSW AUSTRALIA MELBOURNE, AUSTRALIA Melbourne VICTORIA 3000 VIC AUSTRALIA PERTH, AUSTRALIA PERTH WESTERN AUSTRALIA 6155 WA AUSTRALIA VIENNA, AUSTRIA Vienna AUSTRIA A-1180 AUSTRIA MANAMA, BAHRAIN Manama BAHRAIN 319 BAHRAIN DHAKA, BANGLADESH #8815 DHAKA BANGLADESH 1213 BANGLADESH BRUSSELS, BELGIUM BRUSSELS BELGIUM 1210 BELGIUM Bermuda College Paget Bermuda PG04 Bermuda La Paz - Universidad Real La Paz BOLIVIA BOLIVIA GABORONE, BOTSWANA GABORONE BOTSWANA 0000 BOTSWANA Physique Tranformations Gaborone Southeast 0 Botswana BRASILIA, BRAZIL Brasilia DISTRITO FEDERAL 70673-150 BRAZIL BELO HORIZONTE, BRAZIL Belo Horizonte MINAS GERAIS 31140-540 BRAZIL BELO HORIZONTE, BRAZIL Belo Horizonte MINAS GERAIS 30160-011 BRAZIL CURITIBA, BRAZIL Curitiba PARANA 80060-205 BRAZIL RECIFE, BRAZIL Recife PERNAMBUCO 52020-220 BRAZIL RIO DE JANEIRO, BRAZIL Rio de Janeiro RIO DE JANEIRO 22050-001 BRAZIL SAO PAULO, BRAZIL Sao Paulo SAO PAULO 05690-000 BRAZIL SOFIA LAB 1, BULGARIA SOFIA BULGARIA 1000 SOFIA BULGARIA Bow Valley College Calgary ALBERTA T2G 0G5 Canada Calgary - MacLeod Trail S Calgary ALBERTA T2H0M2 CANADA SAIT Testing Centre Calgary ALBERTA T2M 0L4 Canada Edmonton AB Edmonton ALBERTA T5T 2E3 CANADA NorQuest College Edmonton ALBERTA T5J 1L6 Canada Vancouver Island University Nanaimo BRITISH COLUMBIA V9R 5S5 Canada Vancouver - Melville St. Vancouver BRITISH COLUMBIA V6E 3W1 CANADA Winnipeg - Henderson Highway Winnipeg MANITOBA R2G 3Z7 CANADA Academy of Learning - Winnipeg North Winnipeg MB R2W 5J5 Canada Memorial University of Newfoundland St. -

The Gulf Takes Charge in the MENA Region

The Gulf takes charge in the MENA region Edward Burke Sara Bazoobandi Working Paper / Documento de trabajo 9797 April 2010 Working Paper / Documento de trabajo About FRIDE FRIDE is an independent think-tank based in Madrid, focused on issues related to democracy and human rights; peace and security; and humanitarian action and development. FRIDE attempts to influence policy-making and inform pub- lic opinion, through its research in these areas. Working Papers FRIDE’s working papers seek to stimulate wider debate on these issues and present policy-relevant considerations. 9 The Gulf takes charge in the MENA1 region Edward Burke and Sara Bazoobandi April 2010 Edward Burke is a researcher at FRIDE. Sara Bazoobandi is a PhD candidate at Exeter University. In 2009 Sara completed a research fellowship at FRIDE. Working Paper / Documento de trabajo 9797 April 2010 Working Paper / Documento de trabajo This Working paper is supported by the European Commission under the Al-Jisr project. Cover photo: Ammar Abd Rabbo/Flickr © Fundación para las Relaciones Internacionales y el Diálogo Exterior (FRIDE) 2010. Goya, 5-7, Pasaje 2º. 28001 Madrid – SPAIN Tel.: +34 912 44 47 40 – Fax: +34 912 44 47 41 Email: [email protected] All FRIDE publications are available at the FRIDE website: www.fride.org This document is the property of FRIDE. If you would like to copy, reprint or in any way reproduce all or any part, you must request permission. The views expressed by the author do not necessarily reflect the opinion of FRIDE. If you have any comments on this -

Mohammed Bin Salman Doesn't Want to Talk About Jerusalem by Robert Satloff

MENU Policy Analysis / Articles & Op-Eds Mohammed bin Salman Doesn't Want to Talk About Jerusalem by Robert Satloff Dec 14, 2017 Also available in Arabic ABOUT THE AUTHORS Robert Satloff Robert Satloff is executive director of The Washington Institute, a post he assumed in January 1993. Articles & Testimony Saudi Arabia's rulers have lots of worries, but Trump's announcement about the holy city isn't one of them. audi Arabia, the protector of Islam and home to its two holiest sites, is a good place to judge the impact of S President Donald Trump’s recognition of Jerusalem as Israel’s capital on U.S. interests in the region. Set aside the reaction of terrorist groups like Hamas and Hezbollah, and their state sponsors in Tehran and Damascus. And the angry responses from the Palestinian Authority and the Hashemite Kingdom of Jordan, with its large and boisterous Palestinian population, were certainly to be expected. The real question is how America’s friends one step removed from the circle of the Palestinian-Israeli conflict would react. If there were a place one might reasonably expect to hear Muslims expressing thunderous outrage at the handing of Jerusalem to the Jews, it would be in the corridors of power in the Saudi capital of Riyadh. It didn’t happen. Last week, I was in Riyadh leading a delegation of more than 50 supporters and fellows of the Middle East think tank I direct. On Wednesday, just hours before the president made his Jerusalem announcement, we spent five hours in meetings with three different Saudi ministers, discussing everything from crises with Yemen, Qatar, and Lebanon, to the kingdom’s ambitious “Vision 2030” reform program, to the possible public offering of the state oil company Aramco. -

Organizing Around Abundance: Making America an Energy Superpower

Organizing Around Abundance: Making America an Energy Superpower DRAFT 1 Table of Contents Executive Summary ............................................................................................ 3 The Problem with America’s Energy Policy: We Don’t Have One ...................... 7 Principle #1: Promote Responsible Development of Domestic Energy Resources and Construction of Infrastructure to Transport It ...................... 14 Oil and Natural Gas ..........................................................................................14 Keystone XL Pipeline—Build It Now ............................................................14 Property Rights, Federal Lands, and Resource Development ....................15 The Benefits of Increased Natural Gas Production .....................................17 Home Heating Oil ...........................................................................................18 Coal .....................................................................................................................20 Nuclear ...............................................................................................................22 Principle #2: Encourage Technological Innovation of Renewables and Emerging Energy Resources ...................................................................... 25 Principle #3: Unlock the Economic Potential of the Manufacturing Renaissance by Putting America’s Energy Resources to Work ....................... 30 Principle #4: Eliminate Burdensome Regulations .......................................... -

Saudi Arabia Reportedly Paid Twitter Employees to Spy on Users

11/8/2019 Cybersecurity experts say insider spying is an issue beyond Twitter - Business Insider Subscribe Saudi Arabia reportedly paid Twitter employees to spy on users. Cybersecurity experts say insider spying is an issue that goes beyond Twitter. Aaron Holmes 21 hours ago Saudi Crown Prince Mohammed bin Salman, right. Reuters US federal prosecutors have charged two former Twitter employees with spying on users on behalf of Saudi Arabia's government — and experts warn that it could happen again. https://www.businessinsider.com/cybersecurity-experts-say-insider-spying-is-an-issue-beyond-twitter-2019-11 1/5 11/8/2019 Cybersecurity experts say insider spying is an issue beyond Twitter - Business Insider Three cybersecurity experts told Business Insider about broader "insider threats," or the risk of surveillance and data breaches carried out by people employed by tech companies. The experts warned that tech companies should implement safeguards by addressing workplace culture, setting up ways to detect unusual behavior by employees, and more robustly protecting user data across the board. Visit Business Insider's homepage for more stories. Federal charges unsealed Wednesday allege that Saudi Arabia carried out a massive online spying operation, snooping on the accounts of more than 6,000 Twitter users — and prosecutors say the country did it with the help of two Twitter employees. Now, cybersecurity experts warn that similar "insider threats" could surface again if tech companies don't make a concerted eort to ward them o. Twitter responded to the federal charges Wednesday, saying the company was thankful for the investigation and would cooperate with future investigations. -

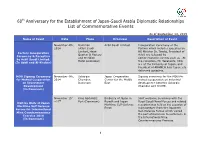

List of the Commemorative Events(PDF)

60th Anniversary for the Establishment of Japan-Saudi Arabia Diplomatic Relationships List of Commemorative Events As of September 14, 2015 Name of Event Date Place Organizer Description of Event November 4th, Damman Azbil Saudi Limited. Inauguration Ceremony of the 2014 (Azbil Saudi Factory which includes speeches by Limited, Head HE Minister Dr. Tawfig, President of Factory Inauguration Quarter & Factory Azbil, etc followed by Ceremony & Reception and Meridien commemorative events such as . At by Azbil Saudi Limited. Hotel Al-Khobar) the reception, Mr. Takahashi, CDA (In Azbil and Al-Khobar) a.i. at the Embassy of Japan, and President of ARAMCO Asia Japan, etc delivered speeches. MOU Signing Ceremony November 4th, Asharqia Japan Cooperation Signing ceremony for the MOU for for Mutual Cooperation 2014 Chamber, Center for the Middle mutual cooperation on industrial on Investment Dammam East development between Asharqia Development Chamber and JCCME. (In Dammam) November 15th King Abdulaziz Embassy of Japan in Joint welcome ceremony with the ~17th Port (Dammam) Riyadh and Japan Royal Saudi Naval Forces and related Visit by Units of Japan Maritime Self-Defense reception was held on the occasion of Maritime Self Defense Force minesweeper from the Japanese Forces for International Self-Defense Forces which visited Mine Countermeasures the port of Dammam to participate in Exercise 2014 the International Mine (In Dammam) Countermeasures Exercise. 1 Name of Event Date Place Organizer Description of Event November 18th King Fahd Cultural Embassy of Japan in The Embassy participated in the 7th ~22nd Center (Riyadh) Riyadh, Ministry of International Children’s Day Festival Culture and and showed a Japanese calligraphy, Participation to the 7th Information Origami, and Japanese traditional International Children’s garments. -

The Changing Geopolitics in the Arab World: Implications of the 2017 Gulf Crisis for Business Jamal Bouoiyour, Refk Selmi

The Changing Geopolitics in the Arab World: Implications of the 2017 Gulf Crisis for Business Jamal Bouoiyour, Refk Selmi To cite this version: Jamal Bouoiyour, Refk Selmi. The Changing Geopolitics in the Arab World: Implications of the 2017 Gulf Crisis for Business. ERF 25th Annual Conference, Mar 2019, Kuwait City, Kuwait. hal- 02071921 HAL Id: hal-02071921 https://hal.archives-ouvertes.fr/hal-02071921 Submitted on 18 Mar 2019 HAL is a multi-disciplinary open access L’archive ouverte pluridisciplinaire HAL, est archive for the deposit and dissemination of sci- destinée au dépôt et à la diffusion de documents entific research documents, whether they are pub- scientifiques de niveau recherche, publiés ou non, lished or not. The documents may come from émanant des établissements d’enseignement et de teaching and research institutions in France or recherche français ou étrangers, des laboratoires abroad, or from public or private research centers. publics ou privés. The Changing Geopolitics in the Arab World: Implications of the 2017 Gulf Crisis for Business Jamal Bouoiyour IRMAPE, ESC Pau Business school, France. CATT, University of Pau, France. E-mail: [email protected] Refk Selmi IRMAPE, ESC Pau Business school, France. CATT, University of Pau, France. E-mail: [email protected] Abstract: The international community was caught by surprise on 5 June 2017 when Saudi Arabia, the United Arab Emirates (UAE), Bahrain and Egypt severed diplomatic ties with Qatar, accusing it of destabilizing the region. More than one year after this diplomatic rift, several questions remain unaddressed. This study focuses on the regional business costs of the year-long blockade on Qatar. -

Russia and Saudi Arabia: Old Disenchantments, New Challenges by John W

STRATEGIC PERSPECTIVES 35 Russia and Saudi Arabia: Old Disenchantments, New Challenges by John W. Parker and Thomas F. Lynch III Center for Strategic Research Institute for National Strategic Studies National Defense University Institute for National Strategic Studies National Defense University The Institute for National Strategic Studies (INSS) is National Defense University’s (NDU’s) dedicated research arm. INSS includes the Center for Strategic Research, Center for the Study of Chinese Military Affairs, and Center for the Study of Weapons of Mass Destruction. The military and civilian analysts and staff who comprise INSS and its subcomponents execute their mission by conducting research and analysis, publishing, and participating in conferences, policy support, and outreach. The mission of INSS is to conduct strategic studies for the Secretary of Defense, Chairman of the Joint Chiefs of Staff, and the unified combatant commands in support of the academic programs at NDU and to perform outreach to other U.S. Government agencies and the broader national security community. Cover: Vladimir Putin presented an artifact made of mammoth tusk to Crown Prince Mohammad bin Salman Al Saud in Riyadh, October 14–15, 2019 (President of Russia Web site) Russia and Saudi Arabia Russia and Saudia Arabia: Old Disenchantments, New Challenges By John W. Parker and Thomas F. Lynch III Institute for National Strategic Studies Strategic Perspectives, No. 35 Series Editor: Denise Natali National Defense University Press Washington, D.C. June 2021 Opinions, conclusions, and recommendations expressed or implied within are solely those of the contributors and do not necessarily represent the views of the Defense Department or any other agency of the Federal Government. -

Federal Register/Vol. 85, No. 226/Monday, November 23, 2020

Federal Register / Vol. 85, No. 226 / Monday, November 23, 2020 / Notices 74763 antitrust plaintiffs to actual damages Fairfax, VA; Elastic Path Software Inc, DEPARTMENT OF JUSTICE under specified circumstances. Vancouver, CANADA; Embrix Inc., Specifically, the following entities Irving, TX; Fujian Newland Software Antitrust Division have become members of the Forum: Engineering Co., Ltd, Fuzhou, CHINA; Notice Pursuant to the National Communications Business Automation Ideas That Work, LLC, Shiloh, IL; IP Cooperative Research and Production Network, South Beach Tower, Total Software S.A, Cali, COLOMBIA; Act of 1993—Pxi Systems Alliance, Inc. SINGAPORE; Boom Broadband Limited, KayCon IT-Consulting, Koln, Liverpool, UNITED KINGDOM; GERMANY; K C Armour & Co, Croydon, Notice is hereby given that, on Evolving Systems, Englewood, CO; AUSTRALIA; Macellan, Montreal, November 2, 2020, pursuant to Section Statflo Inc., Toronto, CANADA; Celona CANADA; Mariner Partners, Saint John, 6(a) of the National Cooperative Technologies, Cupertino, CA; TelcoDR, CANADA; Millicom International Research and Production Act of 1993, Austin, TX; Sybica, Burlington, Cellular S.A., Luxembourg, 15 U.S.C. 4301 et seq. (‘‘the Act’’), PXI CANADA; EDX, Eugene, OR; Mavenir Systems Alliance, Inc. (‘‘PXI Systems’’) Systems, Richardson, TX; C3.ai, LUXEMBOURG; MIND C.T.I. LTD, Yoqneam Ilit, ISRAEL; Minima Global, has filed written notifications Redwood City, CA; Aria Systems Inc., simultaneously with the Attorney San Francisco, CA; Telsy Spa, Torino, London, UNITED KINGDOM; -

GCC Policies Toward the Red Sea, the Horn of Africa and Yemen: Ally-Adversary Dilemmas by Fred H

II. Analysis Crown Prince Sheikh Mohammed bin Zayed Al Nahyan, Abu Dhabi, and King Salman bin Abdulaziz Al Saud, Saudi Arabia, preside over the ‘Sheikh Zayed Heritage Festival 2016’ in Abu Dhabi, UAE, on 4 December 2016. GCC Policies Toward the Red Sea, the Horn of Africa and Yemen: Ally-Adversary Dilemmas by Fred H. Lawson tudies of the foreign policies of the Gulf Cooperation Council (GCC) countries usually ignore import- S ant initiatives that have been undertaken with regard to the Bab al-Mandab region, an area encom- passing the southern end of the Red Sea, the Horn of Africa and Yemen. Saudi Arabia, Qatar and the United Arab Emirates (UAE) have become actively involved in this pivotal geopolitical space over the past decade, and their relations with one another exhibit a marked shift from mutual complementarity to recip- rocal friction. Escalating rivalry and mistrust among these three governments can usefully be explained by what Glenn Snyder calls “the alliance security dilemma.”1 Shift to sustained intervention Saudi Arabia, Qatar and the UAE have been drawn into Bab al-Mandab by three overlapping develop- ments. First, the rise in world food prices that began in the 2000s incentivized GCC states to ramp up investment in agricultural land—Riyadh, Doha and Abu Dhabi all turned to Sudan, Ethiopia, Kenya and Uganda as prospective breadbaskets.2 Doha pushed matters furthest by proposing to construct a massive canal in central Sudan that would have siphoned off more than one percent of the Nile River’s total annual downstream flow to create additional farmland. -

Saudi Arabia-China Relations: a Brave Friendship Or Useful Leverage? Yoel Guzansky and Galia Lavi

ResearchPolicy Analysis Forum Reuters / Lintao Zhang / POOL Saudi Arabia-China Relations: A Brave Friendship or Useful Leverage? Yoel Guzansky and Galia Lavi “China is not necessarily a better friend than the US, but it is a less complicated friend.” Prince Turki al-Faisal Riyadh and Beijing are deepening their economic ties and expanding them in other areas as well. Overall, Saudi-Chinese relations enjoy relative stability but remain limited, inter alia due to China’s lack of interest in deeper involvement in the Middle East at the present time. Aware of Washington’s sensitivities, Riyadh and Beijing do not want to invite pressure from the United States. Saudi Arabia understands that there is no good alternative to the US security guarantees at the present time, but doubts about the credibility of Washington’s political commitment in the long term persist. Moreover, in Riyadh’s view, relations with China can complement its relations with Washington in certain respects, and may even serve as potential leverage over Washington. Keywords: Saudi Arabia, China, United States, Iran, Israel, Pakistan Yoel Guzansky and Galia Lavi | Saudi Arabia-China Relations: A Brave Friendship or Useful Leverage? 109 Introduction Geopolitical Interests With the exception of energy security, the Middle In China’s view, relations with the Gulf states East has long been mostly peripheral to China’s serve diverse interests, first and foremost overall map of interests. However, under the energy security and economic growth. China leadership of Chinese President Xi Jinping, a has publicly expressed its concern about the greater emphasis has been placed on the region friction between the Gulf states and Iran, and in general and the Gulf in particular, an emphasis among the Gulf states themselves, given that that goes beyond purely economic interests.